45. Hydatidiform Mole

Definition

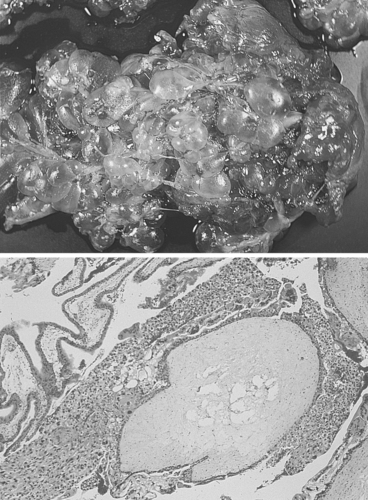

Hydatidiform mole encompasses several conditions, including complete and partial moles, placental site trophoblastic tumors, choriocarcinomas, and invasive moles. Complete moles are devoid of any fetal tissue and the chorionic villi develop grapelike (hydatiform) swelling. In addition, trophoblastic hyperplasia is present. Hydatidiform mole is also called gestational trophoblastic disease.

Incidence

The incidence of hydatidiform mole in Western countries is 1:1000 to 1:1500 pregnancies; in Asia it is 1:120 pregnancies.

Etiology

Hydatidiform mole results from the transfer of only paternal chromosomes, either by single spermatic fertilization of an anucleate ovum, whereupon the paternal DNA replicates, or the fertilization of an ovum by two sperm. The chorionic villi subsequently develop grapelike, or hydatiform swelling.

Signs and Symptoms

• Absent fetal heart tones

• Hyperemesis

• Hyperthyroidism

• Preeclampsia

• Tachycardia

• Tremor

• Uterine enlargement greater than normal for estimated gestational age

• Uterine enlargement smaller than normal for estimated gestational age

• Warm skin

|

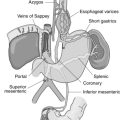

| Hydatidiform Mole. Complete hydatidiform mole. Nearly all villi are enlarged and are interconnected by thin nonedematous cordlike structures. |

Medical Management

Vaginal bleeding is the most common presenting symptom, followed by severe nausea and vomiting. The patient may be hemodynamically unstable on presentation. The first objective is to stabilize the patient via fluid administration, blood transfusion(s), and/or pharmacologic interventions. Any coagulopathy should be corrected. Hypertension should also be treated quickly.

The definitive treatment is uterine evacuation by dilation and curettage. Intravenous oxytocin is administered on dilation of the cervix and should be continued through the postoperative period to decrease the likelihood of hemorrhage. Methergine or Hemabate may be administered rather than oxytocin, particularly if response to oxytocin is deemed inadequate.

The patient may present in respiratory distress, which may stem from several causes, including trophoblastic embolism, high-output congestive heart failure resulting from anemia, and iatrogenic fluid overload.

Complications

• Anemia

• Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC)

• Hemorrhage

• High-output congestive heart failure

• Malignant trophoblastic disease

• Preeclampsia

• Respiratory distress/failure

• Trophoblastic embolism

• Uterine perforation

Anesthesia Implications

The patient with hydatiform mole may arrive at the OR anemic but hypovolemic, and appear as if she is hemoconcentrated. Hemoconcentration may be the result of preeclampsia or general dehydration, possibly from hyperemesis. Intravenous access should be established quickly and should consist of a minimum of one large-bore catheter, although two large-bore catheters would be better. Heart rate and blood pressure should be measured to help determine if the patient is in a compensated state—that is, with low-normal blood pressure accompanied by tachycardia. Skin turgor may indicate a state of dehydration. It may be appropriate to administer a fluid bolus and recheck the patient’s fluid and electrolyte levels along with the hemoglobin and hematocrit values. These measures may help determine whether the patient is truly anemic and better indicate the need for a blood transfusion(s).

The patient who has had hyperemesis may have significant electrolyte imbalances, particularly potassium, that need to be treated in addition to the dehydration and anemia. Additional fluid boluses and potassium supplements may be necessary.

The presence of preeclampsia must be confirmed or ruled out. If present, preeclampsia becomes the primary focus. The patient with preeclampsia should receive the “full complement” of invasive monitoring: central venous catheter, pulmonary artery catheter, and arterial pressure monitoring, along with pharmacotherapy to stabilize, reduce, and control the patient’s blood pressure.

Hemorrhage may be the precipitating factor that brings the patient to the OR. The hemorrhaging will likely worsen with the onset of uterine relaxation. Since all volatile anesthetic agents produce some degree of uterine relaxation, exacerbation of the patient’s hemorrhaging is relatively inevitable. An inhalational anesthetic should be used in the lowest concentration feasible to maintain general anesthesia. Because of the uterine relaxation that may result from inhalational agents, the anesthetist may opt to employ total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA). The anesthetist, in a coordinated effort with the gynecologist, may need to infuse oxytocin to help reduce blood loss regardless of which technique is employed, TIVA or inhalational anesthesia. Care should be taken not to infuse the oxytocin too rapidly because it can produce significant hypotension that may last 3 to 5 minutes without response to vasopressors. Oxytocin is contraindicated in the patient with signs and symptoms of preeclampsia.