CHAPTER 22 Hybrid Arthroplasty

Two-Compartment Approach

Setup and Equipment

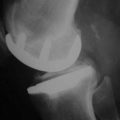

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) continues to be a safe and effective surgical procedure for arthritis of the knee, remaining the gold standard for treatment.1,2 However, from the author’s experience of performing TKAs for over 15 years, several observations are apparent. First, not all total knee replacement patients are happy with their postoperative function. The work of Phil Noble3 suggests that upward of 50% of TKA patients describe some form of functional deficit, particularly side-to-side movement. Such outcomes highlight the necessity of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and how it may relate to functional satisfaction subsequent to knee arthroplasty. The second observation was that the ACL and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) were oftentimes healthy and undamaged at the time of the surgery. It was unsettling to realize that contemporary surgical techniques required the undue resection of these structures. The final observation was the documented combination of wear of the medial compartment and the patellofemoral joint (PFJ), coupled with a nonsymptomatic lateral compartment.4 Resection of the entire articular surface represented further unnecessary sacrifice of healthy tissue.

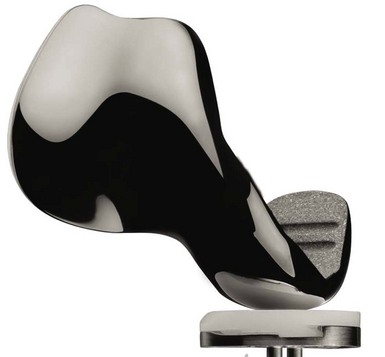

The idea of partial knee arthroplasty to allow retention of the lateral compartment and the cruciate ligaments is not new. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) and patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA) have both been performed now for nearly 30 years.5,6 Replacing the medial compartment alone during UKA, while ignoring arthritic changes at the PFJ, has been recognized as a satisfactory surgical option.7 However, there is significant evidence that osteoarthritis (OA) may progress postoperatively, potentially compromising clinical outcome.8,9 One potential solution is the addition of a PFA to an existing UKA. However, mating these two implants can be technically challenging, via the introduction of three discontinuous zones between the articular cartilage and the implant. In addition to technical considerations, procedure cost must also be considered. The use of two procedures instead of one to address bicompartmental knee disease unnecessarily increases surgical cost. Seven years ago, a monolithic implant was designed to simultaneously replace the medial and the PFJ compartments of the knee (Journey Deuce Bi-Compartmental Knee System; Smith and Nephew, Inc., Memphis, TN) (Fig. 22–1). This device conserves both the ACL and PCL, in addition to sparing the nonsymptomatic lateral compartment. The all-polyethylene or metal-backed medial tibial baseplate is unicompartmental. Initial expectations included a smaller incision, potentially shorter recovery times postoperatively, less pain, reduced blood loss, and improved stability and function.

Approach

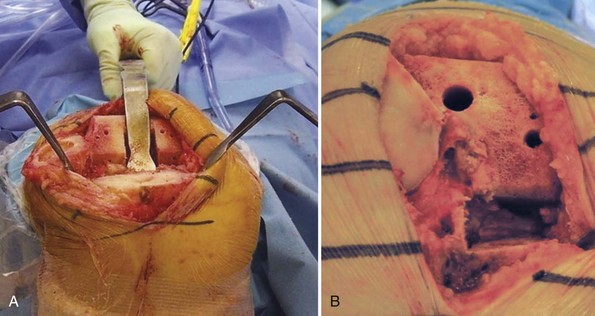

The development of less invasive arthroplasty techniques has been of interest for many years, despite concerns of reduced surgical visualization.10 Assuming relative ease of insertion and acceptable clinical outcomes, it is the author’s opinion that minimally invasive procedures are preferred. With the Deuce knee, the surgeon does not need to visualize the lateral compartment, other than momentarily to assess its integrity. The surgical technique allows for a relatively small incision and ease of insertion. Standard medial-parapatellar arthrotomy has been used for 80% of the author’s patients. Typically, this only involves a 1-inch split into the quadriceps. In 20% of patients, the author has used a midvastus approach without difficulty. This approach is typically reserved for those patients who have not undergone surgery previously, are less muscular, and are more flexible. When comparing the exposure of TKA to that of the Deuce knee, the potential benefits of this procedure are less dependent on incision length. Rather, the conservation of healthy tissue appears to be most important. Specifically, one is not exposing the lateral compartment or the lateral geniculate artery, which can increase pain and reduce postoperative function if not coagulated. Approximately 50% less bone is excised with the Deuce knee compared to traditional TKA. Moreover, the surgeon is able to avoid subluxing the tibia forward, placing a retractor in the lateral gutter, or everting the patella. The resulting reduction in blood loss and tissue tension may further improve postoperative surgical outcome. Surgeons are encouraged to make whatever exposure is necessary to perform the procedure without struggling, as incision length and violation of the quadriceps are not of primary concern with regard to recovery. Furthermore, liberal incision length may reduce risk of malalignment, skin slough, and retained cement.11,12 A comparison of TKA exposure versus that of the Deuce knee is provided in Figure 22–2.

Technical Description (see Video 22-1)

Technical Description (see Video 22-1)

The technique for Deuce implantation begins with tibial preparation, which is similar to that of UKA. The Deuce tibial cutting block utilizes one pin to fixate the cutting block to the tibia, with a second pin utilized for fixation extending under the lateral tibial condyle. The initial pin is placed as a negative stop for the vertical and horizontal resection. This prevents stress risers under the tibial spine or in a vertical direction, helping prevent fracture. The two pins in these locations not only act to fixate the block but also avoid placement of pins in the subchondral bone, which could result in subchondral collapse of the tibial baseplate and subsequent failure of the procedure. A conservative tibial cut of 2–4 mm is made. In most instances, a resection of 2 mm off the lowest point of the tibial articular surface is ideal. If a neutrally aligned knee with medial and PFJ compartment wear exists, a 4-mm cut on the tibia is utilized to prevent overcorrection and overloading of the lateral compartment. A conservative tibial cut is recommended, allowing for neutral varus/valgus placement with a slope of 2–4°. Bicompartmental knee arthroplasty (BKA) with the Deuce knee has been shown to support knee alignment restoration.13 As with UKA, it is important to place the tibial base on the cortical rim without overhang, and to position the component as far laterally as possible without violating the ACL attachment on the tibia. This allows for maximal load to be distributed across the tibia. Spacer blocks allow for the determination of proper knee flexion and extension. Bone cuts similar to that for TKA are made, allowing for correction of extensive varus deformity. In contrast to UKA, balancing the knee in extension can be performed independent of flexion, supporting extensive deformity correction (Fig. 22–3).13,14 Mating the transition zone between the trochlea and lateral femoral condyle was the largest initial technical concern. With revised instrumentation, the author is able to make this process occur in a reproducible manner.

After the cuts have been made, trial implants are used just as in TKA (Fig. 22–4). The patellar component and preparation are the same as those utilized for TKA. A lateral retinacular peel and partial lateral facetectomy are utilized to balance the PFJ articulation. It is even more critical with BKA to perform proper balancing of the PFJ articulation to prevent contact of the lateral facet of the patella with the native lateral femoral condyle at the transition zone. The technical considerations that have been observed in TKA regarding balancing the PFJ need to be highlighted with BKA. In addition to balancing the soft tissue restraints of the lateral retinaculum, shifting the monolithic implant laterally as far as possible without overhang is essential to allowing the proper tracking of the patella within the trochlear groove. The trochlear groove is the same as that of the Genesis II Total Knee System (Smith and Nephew), an implant with a proven track record for PFJ function and excellent clinical outcomes.15,16 Both onlay and inset patella components have been used with good results. However, it is the author’s preference to use a 7.5-mm-thickness three-peg-only patella. This allows for conservation of the patella cut, as well as adequate coverage and positioning of the patella with the implant.

Special Considerations, Indications, and Patient Selection

Clearly, a lateral notch osteophyte on the lateral condyle can and should be excised in each and every case. The necessary excision of this “kissing lesion” is not a contraindication to implantation of the Deuce. Full-thickness lesions of the weight-bearing rail of the lateral femoral condyle should not be accepted; in this case, conversion to TKA is recommended. Additional special considerations include the neutrally aligned knee with medial compartment arthrosis and an open lateral compartment. Most medial compartment arthritic knees result in varus deformity. Occasionally, based on the anatomy of the femur and tibia, radiographs may reveal medial and PFJ arthritis with a nonsymptomatic lateral compartment. When this occurs, it is critical to resect more bone on the tibial side to avoid overcorrection. Patella baja may result from high tibial valgus osteotomy (Box 22–1). In this instance the patella is brought in contact with the native cartilage in the transition zone, which is not optimal. Moreover, the closing wedge high tibial osteotomy results in a neutrally aligned medial compartment that is at risk for overcorrection. In both cases, conversion to TKA is necessary.

Postsurgical Follow-Up

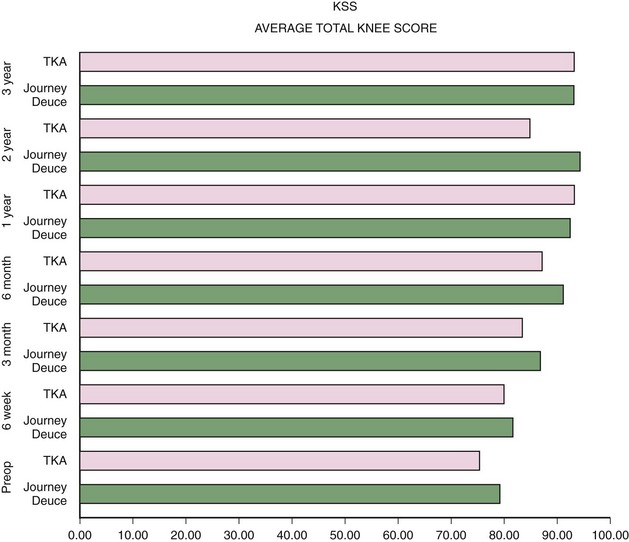

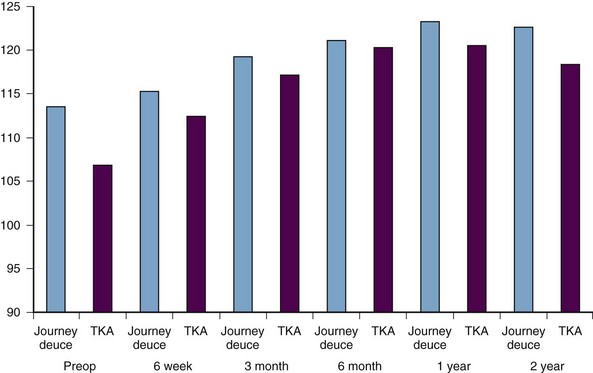

As previously noted, one of the potential benefits of Deuce implantation is improved recovery. By conserving healthy tissue and minimizing joint trauma during surgery, postoperative function may be improved. Early evidence supports this hypothesis. In a gait study of 8 BKA patients and 10 controls,17 the Deuce was found to support normal frontal plane mechanics and extensor moments about the knee during walking. At 1.2 years following surgery, Deuce patients had largely returned to normal function. Regarding clinical outcomes, the author has collected postoperative data during a single-surgeon survey of 400 Deuce and 152 TKA patients matched for body mass index and age (65 years for Deuce; 66 years for TKA). The average follow-up for the Deuce group is 29 months versus 22 months for TKA. The average total Knee Society score for the Deuce currently exceeds that of the TKA group at nearly every interval through 3 years, surpassing 90 by 6 months (Fig. 22–5). This is likewise the case for range of motion at every interval through 3 years (Fig. 22–6).

Conclusions

The author’s experience with the Deuce knee suggests that this device can be effectively utilized to treat BKA patients with symptomatic medial and PFJ compartments. While TKA is an effective treatment for bicompartmental disease, evidence supports improved functional outcomes following BKA with the Deuce.17 This appears to be due primarily to ACL preservation and reduced bone resection, tissue distress, and blood loss during implantation. Moreover, the author’s survey of 800 Deuce patients supports the stability of the Deuce knee at 2.5 years follow-up. BKA is a viable procedure for a significant number of OA patients.8,9 Although additional research is necessary to address mid- to long-term outcomes, the current procedure will likely have a place in the orthopaedics reconstructive market for years to come.

1 Hart JA. Joint replacement surgery. Med J Aust. 2004;180:S27-S30.

2 Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, et al. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990–2002. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2005;87:1487-1497.

3 Noble PC, Conditt MA, Cook KF, Mathis KB. The John Insall Award. Patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:35-43.

4 Ledingham J, Regan M, Jones A, Doherty M. Radiographic patterns and associations of osteoarthritis of the knee in patients referred to hospital. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:520-526.

5 Borus T, Thornhill T. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:9-18.

6 Leadbetter WB, Ragland PS, Mont MA. The appropriate use of patellofemoral arthroplasty: an analysis of reported indications, contraindications, and failures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;436:91-99.

7 Kendrick BJ, Rout R, Bottomley NJ, et al. The implications of damage to the lateral femoral condyle on medial unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2010;92:374-379.

8 Berger RA, Meneghini RM, Sheinkop MB, et al. The progression of patellofemoral arthrosis after medial unicompartmental replacement: results at 11 to 15 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428:92-99.

9 Hernigou P, Deschamps G. Patellar impingment following unicompartmental arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2002;84:1132-1137.

10 Khanna A, Gougoulias N, Longo UG, Maffulli N. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty: a systemic review. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009;40:479-489.

11 Berenc KR, Lombardi AV. Avoiding the potential pitfalls of minimally invasive total knee surgery. Orthopedics. 2005;289:1326-1330.

12 Dalury DF, Dennis DA. Mini-incision total knee arthroplasty can increase risk of component malalignment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;440:77-81.

13 Rolston L, Siewart K. Assessment of knee alignment after bicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1111-1114.

14 Emerson RH, Higgins LL. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty with the Oxford prosthesis in patients with medial compartment arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2008;90:118-122.

15 Bourne RB, Laskin RS, Guerin JS. Ten-year results of the first 100 Genesis II total knee replacement procedures. Orthopedics. 2007;30:S83-S85.

16 Crockarell JR, Hicks JM, Schroeder RJ, et al. Total knee arthroplasty with asymmetric femoral condyles and tibial tray. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:108113.

17 Wang H, Dugan E, Frame J, Rolston L. Gait analysis after bi-compartmental knee replacement. Clin Biomech. 2009;24:751-754.