Chapter 54 Humeral Shaft Fractures: What Is the Best Treatment?

Fractures of the humeral shaft represent approximately 5% of all fractures.1 The majority of humeral shaft fractures are currently treated without surgery in North America and Europe, a fact reflected in the following quote: “Because closed methods of treatment for humeral shaft fractures have a high rate of success, open reduction is rarely indicated.”2 The indications for operative reduction and fixation of humeral diaphysis fractures, first defined by Bandi3 in 1964 and now found in most articles and textbooks, include failed conservative management (unable to maintain adequate reduction), open fracture, bilateral humeral shaft fractures, fractures with vascular injury/compromise, polytrauma victim with humeral shaft fracture, pathologic fracture, ipsilateral humeral shaft and forearm fractures (floating elbow), and segmental fractures.4 These recommendations are based on expert opinion rather than comparative outcome studies.

OPERATIVE VERSUS NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Currently, no prospective trials have compared the outcomes of operative and nonoperative treatment of these fractures. In one study, Ekholm and coauthors5 report on a cohort of 78 patients evaluated retrospectively after conservative treatment of humeral shaft fractures with fracture brace treatment. The nonunion rate overall was 10% but increased to 20% for AO/OTA (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association) type A fractures of the midshaft and more proximal diaphysis. Outcome scores were worse for those who went on to nonunion and required open reduction and internal fixation. Even in those who healed successfully with nonoperative care, only 50% reported full recovery. The authors conclude that plate fixation should be considered for some fracture subtypes (Level V).

Operative Management: Compression Plating versus Statically Locked Intramedullary Nail

Since the advent of intramedullary nails designed for humeral shaft fractures, controversy has existed regarding the superiority of compression plating versus statically locked nailing of these fractures.6 Advantages of nailing include a remote entry point preserving the biological environment for fracture healing; intramedullary reaming and fixation, eliminating risk for injury to the radial nerve (as long as no nerve interposition occurs); load sharing by the device; and more rapid surgery with less blood loss and muscle damage. In contrast, the advantages of plate fixation include a direct approach to the fracture site with no violation of the proximal humerus and, more importantly, the rotator cuff; no risk of shoulder impingement from prominent subacromial hardware; direct visualization and protection of the radial nerve depending on fracture level and approach; the possibility of rigid compressive fixation; and the opportunity for bone grafting or radial nerve exploration, or both, if needed. Both options permit rapid mobilization of the shoulder and elbow.

A number of prospective, randomized studies have compared plating and nailing of humeral shaft fractures. Rodrigues-Merchan7 compared open reduction and compression plating with closed reduction and intramedullary fixation with Hackethal nails in 40 patients who did not respond successfully to conservative treatment. Given the lack of interlocking, the nailing group required 6 months of postoperative bracing. All except one of the former group required reoperation for hardware removal. No nonunions occurred, and delayed union and functional results were identical in both groups. The author concludes that the treatments were equivalent in healing and functional outcome, but that the nailing group required systematic hardware removal and prolonged bracing.

Chiu and colleagues8 randomized 91 patients to 3 groups: open reduction and plate fixation, with and without bone graft, and closed reduction and nailing with flexible Enders nails without interlocking. Surgical time, blood loss, and length of stay were lowest in the nailing group. Time to union was increased in the group undergoing plating without bone graft. Overall, complications were more likely to occur in the plating without bone graft and the nailing groups, including a statistically greater rate of nonunion when compared with plating with bone graft. Infection and iatrogenic nerve injury were similar in all three groups. All patients reported satisfactory results according to functional parameters set out by the authors. The authors conclude that, in cases where operative time was a consideration (e.g., patient with polytrauma injuries), Enders nailing appeared superior. Overall, union was best assured with plating plus bone graft.

In 2000, McCormack and coauthors9 reported the first published prospective, randomized trial comparing plating with statically locked intramedullary nailing. A total of 44 patients were randomly assigned to plating or locked nailing. Initially, nailing was antegrade, but then it was switched to retrograde based on reports of shoulder complications with the former technique. No statistical difference was detected in terms of pain, shoulder function (using validated outcome measures), union, alignment, blood loss, and operative time. Complications were significantly more common in the nailing group, however (62% vs. 13% in the plating group), whereas secondary surgery was required in 33% of nailing patients compared with 4% of plating patients. Fewer complications occurred with retrograde nailing compared with antegrade nailing. Surprisingly, iatrogenic radial nerve injury occurred in 14% (3/21) of nailing patients, with none in the plating group. These findings led the authors to recommend plating as the standard for fixation of humeral shaft fractures, reserving nailing for specific situations such as pathologic and segmental fractures.

In a larger randomized study, Chapman and researchers10 compared plating and antegrade locked intramedullary nailing in 84 patients. No difference in time to union and rate of nonunion was detected. Significantly more patients described shoulder pain and had decreased shoulder range of motion in the nailing group, whereas fixed flexion contracture of the elbow was more common in the plating group, especially in distal third fractures. The authors conclude that healing was comparable with the two techniques with more pain and stiffness in the shoulder secondary to nailing.

To improve the inferences from the small, prospective, randomized trials comparing plating and locked intramedullary nailing in humeral shaft fractures, Bhandari and investigators11 undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess their effects on rates of reoperation and other secondary outcomes. Three studies were pooled9,10, 12 after confirming overall study quality. The relative risk of reoperation with plating was determined to be 0.3 (95% confidence interval, 0.07–0.9; P = 0.03), translating into a relative risk reduction of 74% compared with nailing. The relative risk of shoulder impingement was also reduced with plating (0.1; 95% confidence interval, 0.03–0.4; P = 0.002), resulting in a relative risk reduction of 90%. Analysis of secondary outcomes such as nonunion, infection, and iatrogenic nerve injury revealed no increased risk with plating when compared with nailing. The authors conclude that, given a total of only 155 randomized patients across 3 studies, these results need to be interpreted with care and called for a much larger definitive trial to determine the true treatment effects of intramedullary nails and compression plates in humeral shaft fractures.11

INTRAMEDULLARY NAILING: ANTEGRADE VERSUS RETROGRADE

The initial enthusiasm accompanying the advent of antegrade locked intramedullary nailing of humeral shaft fractures was dampened by reports of subsequent shoulder pain.13,14 This was attributed to rotator cuff and/or humeral head injury during insertion, as well as potentially prominent hardware provoking subacromial impingement. A retrograde insertion technique was developed to avoid these complications.

In a nonrandomized, prospective cohort study, Blum and coauthors15 compared the antegrade and retrograde insertion techniques using an identical implant. Eighty-four acute diaphyseal fractures underwent nailing, two thirds retrograde and one third antegrade, based on surgeon preference. Iatrogenic fracture at the insertion point was seen in 5% of retrograde patients, a well-recognized complication of this technique. Nonunion occurred in 9% (5/57) of the retrograde group, with none in the antegrade group. Of these, the majority (4/5) was “hypotrophic” in nature, and all resolved with secondary surgery. The second primary outcome evaluated was pain and function. Overall, 6% (5/84) of patients reported significant shoulder pain. Interestingly, two of these five patients had undergone retrograde nailing. One case of elbow pain occurred in each of the groups. In terms of shoulder function, 3.7% of antegrade patients described poor function compared with 1.8% of the retrograde group. However, this advantage was lost when the 1.8% rate of poor elbow function seen in the retrograde group was added. Overall, intraoperative complications and nonunion results were greater in the retrograde group, with overall rates of pain and poor function similar in both cohorts.

EXTERNAL FIXATION OF HUMERAL SHAFT FRACTURES

No comparative studies exist to clarify the role of external in the fixation of humeral shaft fractures. This technique is currently reserved for specific clinical situations.16 These include temporary stabilization in the polytrauma patient while awaiting improved physiologic parameters for more definitive fixation. Contaminated open fractures can be stabilized with external fixation until soft-tissue decontamination is completed by serial debridements. Fractures involving nerve or arterial injury requiring reconstruction can also benefit from external fixation for stabilization. In the nonacute setting, nonunion (whether sterile or infected) can be successfully treated with this type of fixation.17

When indications exist for operative care of a humeral shaft fracture, open reduction and compression plating appears to be superior to intramedullary fixation with regards to rate of reoperation and shoulder impingement, but not for nonunion, infection, and iatrogenic nerve injury. As Bhandari and investigators11 point out, these recommendations are based on a low number of patients, and larger prospective trials are necessary to draw more certain conclusions.11

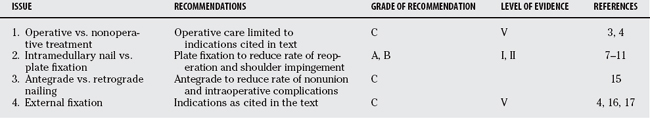

External fixation has a definite but limited role to play in humeral shaft fracture fixation. Currently, this technique is limited to provisional fixation in open fractures and patients with multiple trauma injuries, as well as in the treatment of nonunions. Table 54-1 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of humeral shaft fractures.

1 Crolla RM, de Vries LS, Clevers GJ. Locked intramedullary nailing of humeral fractures. Injury. 1993;24:403-406.

2 Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholz RW, editors. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 3rd ed. 1991; JB Lippincott: Philadelphia; 853.

3 Bandi W. Indikation und Technik der Osteosynthese am Humerus. Helv Chir Acta. 1964;31:89-100.

4 Sarmiento A, Waddell JP, Latta LL. Diaphyseal humeral fractures: Treatment options. Instr Course Lect. 2002;51:257-269.

5 Ekholm R, Tidermark J, Tornkvist H, et al. Outcome after closed functional treatment of humeral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:591-596.

6 Haberneck H, Orthner E. A locking nail for fractures of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73-B:651-653.

7 Rodrigues-Merchan EC. Compression plating versus hackethal nailing in closed humeral shaft fractures failing nonoperative reduction. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9:194-197.

8 Chiu FY, Chen CM, Lin CF, et al. Closed humeral shaft fractures: A prospective evaluation of surgical treatment. J Trauma. 1997;43:947-951.

9 McCormack RG, Brien D, Buckley RE, et al. Fixation of fractures of the shaft of the humerus by dynamic compression plate or intramedullary nail. A prospective, randomised trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82B:336-339.

10 Chapman JR, Henley MB, Agel J, Benca PJ. Randomized prospective study of humeral shaft fracture fixation: Intramedullary nails versus plates. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:162-166.

11 Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, McKee MD, Schemitsch EH. Compression plating versus intramedullary nailing of humeral shaft fractures—a meta-analysis. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:279-284.

12 Bolano LE, Iaquinto JA, Vasicek V: Operative treatment of humerus shaft fractures: A prospective randomized study comparing intramedullary nailing with dynamic compression plating. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Orlando, Florida, Feb 15–19, 1995.

13 Chapman J, Weber TG, Henley MB, Benca PJ: Randomized prospective study of humerus fixation: nails versus plates. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, Tampa Bay, Florida, Sept 29–Oct 1, 1995, pp 104–105.

14 Wagner MS, Patterson BM, Wilber JH, Sontich JK: Comparison of outcomes for humeral diaphysis fractures treated with either closed intramedullary nailing or open reduction internal fixation using a dynamic compression plate in the multiple trauma patient. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, Tampa Bay, Florida, Sept 29–Oct 1, 1995, pp 102–103.

15 Blum J, Janzing H, Gahr R, et al. Clinical performance of a new medullary humeral nail: Antegrade versus retrograde insertion. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:342-349.

16 Ruland WO. Is there a place for external fixation in humeral shaft fractures? Injury. 2000;31(suppl):27-34.

17 Lammens J, Bauduin G, Driesen R, et al. Treatment of nonunion of the humerus using the Ilizarov external fixator. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;353:223-230.