Human immunodeficiency virus disease and immunodeficiency syndromes

Immunodeficiency results from absence or failure of one or more elements of the immune system. It may be acquired, e.g. acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), or inherited, e.g. chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease

Infection with HIV is a progressive process that mostly leads to the development of AIDS.

Clinical presentation

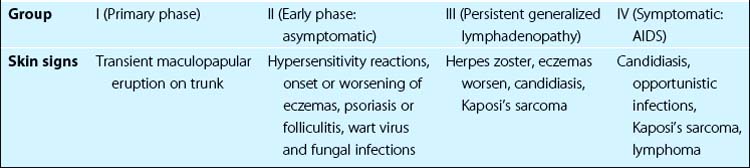

As the disease progresses, the number of CD4+ lymphocytes falls and, when the blood count is below 50 cells/mL in the late phase of HIV infection (AIDS), M. avium complex infection, lymphoma and encephalopathy may develop. The mean latent period between infection and the development of AIDS is 10 years. Skin signs include the following (Table 1):

Dry skin. Skin dryness, often with asteatotic eczema, and seborrhoeic dermatitis (Fig. 1) are common and early findings. Their severity increases as the disease advances.

Dry skin. Skin dryness, often with asteatotic eczema, and seborrhoeic dermatitis (Fig. 1) are common and early findings. Their severity increases as the disease advances.

Fungal and papillomavirus infections. Tinea infections and perianal and common viral warts are seen in early disease.

Fungal and papillomavirus infections. Tinea infections and perianal and common viral warts are seen in early disease.

Acne and folliculitis. These worsen in early and mid-stage disease.

Acne and folliculitis. These worsen in early and mid-stage disease.

Other infections. Oral candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia (thought to be associated with Epstein–Barr virus; Fig. 2) and infection with herpes simplex, herpes zoster, molluscum contagiosum and Staphylococcus aureus are increased in advanced disease.

Other infections. Oral candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia (thought to be associated with Epstein–Barr virus; Fig. 2) and infection with herpes simplex, herpes zoster, molluscum contagiosum and Staphylococcus aureus are increased in advanced disease.

Other dermatoses. Drug eruptions, hyperpigmentation and basal cell carcinomas are more common; psoriasis can get worse and syphilis may coexist.

Other dermatoses. Drug eruptions, hyperpigmentation and basal cell carcinomas are more common; psoriasis can get worse and syphilis may coexist.

Kaposi’s sarcoma. Kaposi’s sarcoma is a multicentric tumour of vascular endothelium seen in a third of patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex, particularly in male homosexuals. It presents as purplish nodules or macules on the face, limbs, trunk or in the mouth (Fig. 3), but often also involves the internal organs and lymph nodes. Kaposi’s sarcoma is due to co-infection with herpes virus 8. A more benign sporadic form, seen in elderly East European Jewish men, is not associated with HIV.

Kaposi’s sarcoma. Kaposi’s sarcoma is a multicentric tumour of vascular endothelium seen in a third of patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex, particularly in male homosexuals. It presents as purplish nodules or macules on the face, limbs, trunk or in the mouth (Fig. 3), but often also involves the internal organs and lymph nodes. Kaposi’s sarcoma is due to co-infection with herpes virus 8. A more benign sporadic form, seen in elderly East European Jewish men, is not associated with HIV.

Lymphoma. Lymphomas seen with late-phase HIV infection are often extranodal and sometimes cutaneous.

Lymphoma. Lymphomas seen with late-phase HIV infection are often extranodal and sometimes cutaneous.

Management

Clinical diagnosis of HIV infection is confirmed by a blood test for the virus by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the disease is staged by measurement of CD4+ count and viral load by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Other co-transmitted diseases (including syphilis and hepatitis C) and tuberculosis should be tested for. Patients should be managed in departments with special experience in HIV disease. Infected individuals are counselled and sexual contacts are traced. Without antiretroviral therapy, 5 years after HIV infection, 15% will have progressed to AIDS, but two-thirds of the remainder will be asymptomatic. Ten years after infection, 50% will have developed AIDS, of whom 80% will have died. After AIDS has developed, mortality is high, with 50% dying in 1 year and 85% in 5 years. About 20–50% of infants born to HIV-infected women have HIV disease.

Congenital immune deficiency syndromes

Congenital immune deficiency syndromes are divided into:

B cell deficiency: immunoglobulin deficit; sometimes combined with …

B cell deficiency: immunoglobulin deficit; sometimes combined with …

T cell deficiency: impairment of cell-mediated immunity (see p. 11).

T cell deficiency: impairment of cell-mediated immunity (see p. 11).

Defects in effector mechanisms such as complement or neutrophils.

Defects in effector mechanisms such as complement or neutrophils.

X-linked agammaglobulinaemia. Infections occur in infancy once maternal antibodies run out.

X-linked agammaglobulinaemia. Infections occur in infancy once maternal antibodies run out.

IgA deficiency. Affects 1 in 700 caucasians; half have recurrent infections.

IgA deficiency. Affects 1 in 700 caucasians; half have recurrent infections.

Severe combined immune deficiency. Fatal in infancy because of overwhelming infection unless treated by bone marrow transplant.

Severe combined immune deficiency. Fatal in infancy because of overwhelming infection unless treated by bone marrow transplant.

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome. X-linked with T cell defects, thrombocytopenia and an associated eczema.

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome. X-linked with T cell defects, thrombocytopenia and an associated eczema.

Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Seen with severe immune deficiencies, multiple endocrine dysfunction or occurring sporadically; mainly due to a T cell defect. Candidiasis usually involves the mouth, skin or nails (Fig. 4).

Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Seen with severe immune deficiencies, multiple endocrine dysfunction or occurring sporadically; mainly due to a T cell defect. Candidiasis usually involves the mouth, skin or nails (Fig. 4).

Skin signs of immunosuppression for allografts

The use of corticosteroids, azathioprine and ciclosporin for the suppression of allograft rejection is well established. Cutaneous side-effects include not only drug eruptions and side-effects from the drugs but also infections and tumours, which develop as a result of impairment of immune surveillance, and graft-versus-host disease, which is a manifestation of an immune reaction against the host’s body by the grafted tissue (p. 83). Recipients of renal allografts seem to be at particular risk of developing skin cancers. Specific skin problems in immunosuppressed allograft recipients include the following:

Infections and infestations. Herpes zoster (p. 55), herpes simplex and cytomegalovirus infection may be reactivated with immunosuppressive therapy. Boils and cellulitis are common, and crusted ‘Norwegian’ scabies (p. 118) may occur.

Infections and infestations. Herpes zoster (p. 55), herpes simplex and cytomegalovirus infection may be reactivated with immunosuppressive therapy. Boils and cellulitis are common, and crusted ‘Norwegian’ scabies (p. 118) may occur.

Human papillomavirus infection. About 50% of renal transplant patients have viral warts (Fig. 5). These may be associated with actinic keratoses or other dysplastic lesions on sun-exposed sites. The human papillomavirus acts as a carcinogen along with sun exposure.

Human papillomavirus infection. About 50% of renal transplant patients have viral warts (Fig. 5). These may be associated with actinic keratoses or other dysplastic lesions on sun-exposed sites. The human papillomavirus acts as a carcinogen along with sun exposure.

Skin cancers. The risk of skin cancer in renal transplant recipients is increased 20-fold compared with the normal population. Squamous cell carcinomas (Fig. 6) are more common than basal cell carcinomas. The tumours may look clinically and histologically banal but behave aggressively. Malignant melanoma is also more common.

Skin cancers. The risk of skin cancer in renal transplant recipients is increased 20-fold compared with the normal population. Squamous cell carcinomas (Fig. 6) are more common than basal cell carcinomas. The tumours may look clinically and histologically banal but behave aggressively. Malignant melanoma is also more common.

HIV disease and immunosuppression

HIV infection may be asymptomatic for several years. Skin signs of early HIV disease include dry skin and seborrhoeic dermatitis; signs of late disease are extensive infections, oral candidiasis and Kaposi’s sarcoma. HAART and the prevention of opportunistic infection have transformed the outlook for patients with HIV.

HIV infection may be asymptomatic for several years. Skin signs of early HIV disease include dry skin and seborrhoeic dermatitis; signs of late disease are extensive infections, oral candidiasis and Kaposi’s sarcoma. HAART and the prevention of opportunistic infection have transformed the outlook for patients with HIV.

Congenital immune deficiency syndromes are rare, often present with failure to thrive in infancy and are associated with opportunistic or pyogenic infections.

Congenital immune deficiency syndromes are rare, often present with failure to thrive in infancy and are associated with opportunistic or pyogenic infections.

Immunosuppression for allografts is particularly associated with human papillomavirus infection, squamous cell carcinomas or dysplastic lesions, and graft-versus-host disease.

Immunosuppression for allografts is particularly associated with human papillomavirus infection, squamous cell carcinomas or dysplastic lesions, and graft-versus-host disease.