95 Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Diagnosis

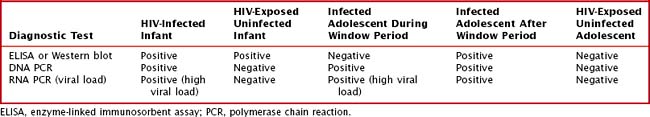

Table 95-1 summarizes the expected results of HIV diagnostic tests for HIV-exposed and -infected infants and adolescents. Children older than the age of 18 months would have the same test results as adolescents in the same infection or exposure category.

Clinical Manifestations of Hiv Infection

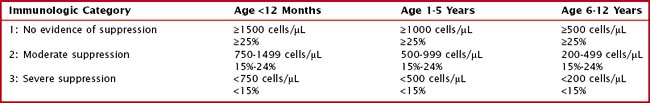

The process of HIV replication leads to depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes. The degree of immunologic suppression is classified based on the number and percent of CD4+ T lymphocytes present in the bloodstream. In young children, the normal number of CD4+ T lymphocytes is much higher than in adults. Therefore, age-specific absolute CD4+ T lymphocyte count ranges should be used to determine the degree of immune suppression in children. CD4+ T lymphocyte percents change less with age and can be used instead of absolute counts to classify the degree of immune suppression in HIV-infected children (Table 95-2).

Table 95-2 Immunologic Categorization Based on Age-Specific CD4+ T-Lymphocyte Counts and Percent of Total Lymphocytes

Along with depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes, HIV infection leads to functional defects in existing CD4+ T-lymphocytes and defects in B-cell function. These combined immunosuppressive processes lead to a number of clinical manifestations. The most severe and common of these manifestations are outlined in Table 95-3. Opportunistic infections, cancers, hematologic aberrations, and other noninfectious manifestations are among the most severe AIDS-defining conditions.

Table 95-3 Selected Clinical Manifestations of HIV Infection

| Severe Manifestations | Description |

|---|---|

| Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia | Definitive diagnosis via microscopy of induced sputum or BAL |

| Multiple or recurrent serious bacterial infections | Septicemia, pneumonia, meningitis, bone or joint infection, internal organ infections |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | Characterized by pink or purple lesions on the skin and soft tissues; diagnosis is confirmed with biopsy |

| Lymphoma | Cerebral or B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Mycobacterial infections | Extrapulmonary mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections |

| HIV encephalopathy | Failure to attain or loss of developmental milestones or loss of intellectual ability, impaired brain growth, or acquired symmetric motor deficits lasting for >2 mo without a cause other than HIV |

| HIV wasting syndrome | Unexplained severe wasting, stunting, or severe malnutrition not adequately responding to standard therapy |

| Severe herpes simplex infections | Bronchitis, pneumonitis, esophagitis (or mucocutaneous ulcer persisting >1 mo) |

| Severe candidiasis | Esophageal or pulmonary (including bronchi and trachea) |

| Moderately Severe Manifestations | |

| Single episode of serious bacterial infection | Septicemia, pneumonia, meningitis, bone or joint infection, internal organ infections |

| Lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis | Definitive diagnosis via biopsy but characterized by chronic bilateral reticulonodular interstitial pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxemia |

| Recurrent or chronic diarrhea | Persistent ≥14 days |

| Anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia persisting ≥30 days | Anemia: hemoglobin <8 g/dL Neutropenia: ANC <1000 cells/mm3 Thrombocytopenia: platelets <100,000 cells/mm3 |

| Herpes zoster | At least two distinct episodes or more than one dermatome |

| Herpes simplex virus | Recurrent stomatitis (>two episodes in 1 year) |

| Complicated varicella | Disseminated or severe chicken pox |

| Candidiasis | Oropharyngeal lasting for >2 mo |

| Mild Manifestations | |

| Lymphadenopathy | ≥0.5 cm at more than two sites |

| Recurrent or persistent upper respiratory tract infections | Including sinusitis or otitis media |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | Unexplained, persistent |

| Mucocutaneous lesions | Extensive wart virus infection, extensive molluscum contagiosum, popular pruritic eruptions, recurrent oral ulcers |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage.

Treatment

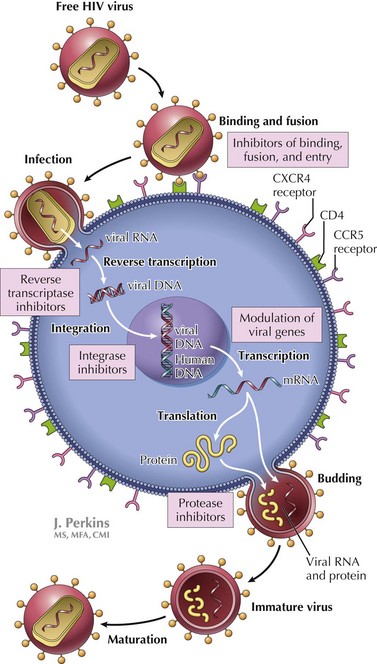

Figure 95-1 shows the life cycle as well as the targets of antiretroviral medications.

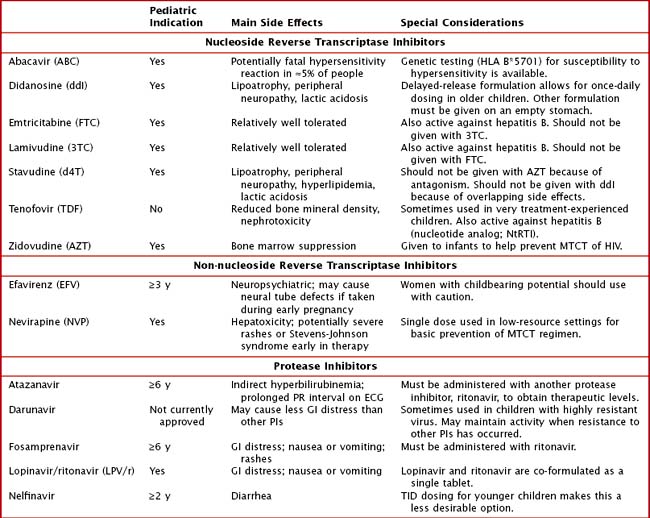

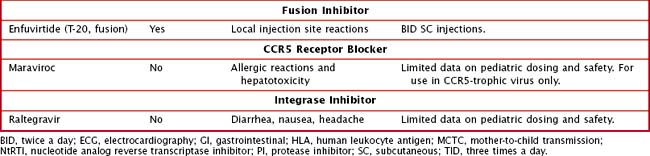

Table 95-4 describes key features of the antiretroviral medications most commonly used for treatment of children with HIV. To maintain long-term effectiveness, these drugs must be given in appropriate combinations and adherence to therapy must be excellent. Adherence is sometimes complicated by drug side effects. The PIs often cause gastrointestinal distress, particularly early in therapy, that make medication tolerance challenging. Many of the drugs have significant long-term effects, including hyperlipidemia, body habitus changes, and peripheral neuropathy. Careful monitoring by doctors who are experienced in the treatment of HIV allows for early detection of problems and appropriate adjustment of regimens to help ensure long-term therapeutic success.

For children with severe HIV-related immunosuppression, prophylactic medications should also be given to help prevent opportunistic infections. Common infections in children without HIV are also seen in children with HIV but frequently are more severe. Therefore, routine vaccination of HIV-infected children is essential. Table 95-5 outlines recommended strategies for primary prevention of infectious complications in children with HIV. After treatment of an opportunistic infection, long-term secondary prophylaxis is often given to prevent recurrence of disease, regardless of immunologic recovery.

Table 95-5 Primary Prophylaxis of Opportunistic Infection in HIV

| Infection | Indications for Prophylaxis | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia |

MMR, mumps, measles, and rubella; TB, tuberculosis; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim−sulfamethoxazole.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral and revised recommendations for HIV screening of pregnant women. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(RR-19):1-110. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5019.pdf

Mofenson LM, Brady MT, Danner SP, et al. Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections among HIV-Exposed and HIV-Infected Children. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/Pediatric_OI.pdf

HIV Paediatric Prognostic Markers Collaborative Study and the CASCADE CollaborationDunn D, Woodburn P, et al. Current CD4 cell count and the short-term risk of AIDS and death before the availability of effective antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children and adults. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(3):398-404.

Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. February 23 http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/PediatricGuidelines.pdf, 2009.

World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Therapy of HIV Infection in Infants and Children in Resource-Limited Settings: Toward Universal Access. http://www.who.int/hiv/en, 2006. Available at

World Health Organization. Towards Universal Access: Scaling up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector. 2008 Progress Report. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf.