Chapter 28 HOW TO PREPARE PATIENTS FOR ENDOSCOPIC PROCEDURES

Correct patient preparation involves:

INTRODUCTION

ASSESSMENT OF PATIENT FITNESS FOR PROCEDURE

Health professionals assessing patients for endoscopy should be aware of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification of patient risk (see Table 28.1). The degree of concern will be dictated somewhat by the level of anaesthetic support available for the procedure (which ranges between institutions from none to an anaesthesiologist, as well as varying for different types of procedures). In general, procedures on ASA class I and most class II patients can be safely performed in a well equipped endoscopy suite with appropriately trained staff. ASA class III patients might be better triaged to the operating room. This degree of patient risk must be identified prior to the endoscopy list so that appropriate patient assessment (and informed consent) can be undertaken as well as ensuring that the procedure is performed in the appropriate environment.

Table 28.1 Definition of American Society for Anesthesiologists comorbidity status

| Class 1 | Patient has no organic, physiologic, biochemical or psychiatric disturbance. The pathologic process for which the operation is to be performed is localised and does not entail systemic disturbance |

| Class 2 | Mild to moderate systemic disturbance caused by either the condition to be treated surgically or by other pathophysiologic processes |

| Class 3 | Severe systemic disturbance or disease from whatever cause, even though it may not be possible to define the degree of disability with finality |

| Class 4 | Severe systemic disorders that are life-threatening, not always correctable by operation |

| Class 5 | The moribund patient who has little chance of survival but is submitted to the operation in desperation |

PROCEDURE-SPECIFIC ISSUES

Gastroscopy and endoscopic ultrasound

The main issue for gastroscopy (also known as oesophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD] or simply ‘endoscopy’) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is safety to the patient through ensuring an empty stomach. Patients should not eat solid food for at least 6 hours or clear liquids for 4 hours prior to a gastroscopy. If the patient is known to have poor gastric emptying fasting for longer or dietary restriction to clear fluids for 24–48 hours prior to the procedure should be considered. In the emergency situation, airway protection via endotracheal tube should be considered.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Patients with biliary obstruction should receive prophylactic antibiotics prior to the commencement of the procedure (see below for a more detailed discussion of antibiotic prophylaxis). Endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) of the ampulla of Vater is a common procedure during ERCP. Patients in whom ES is considered should have an international noramalised ratio (INR) <1.7 (ideally normalised) and should not take IIb/IIIa inhibitors such as clopidogrel for 7–10 days if the procedure is elective. Aspirin use does not preclude ES, but ideally should also be ceased 5 days before the procedure.

Colonoscopy

Preparation for lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Acute massive haematochezia should be investigated with colonoscopy following a rapid purge. This usually involves at least 3–4 L PEG-based solution, until the effluent is pink. In patients unable to drink the solution, it may be administered using a nasogastric tube. A prokinetic agent may be helpful to speed this process. It should be noted that the passage of bright red blood per rectum in a haemodynamically unstable patient could be due to a duodenal source of bleeding, so these patients will often have an emergency upper endoscopy first.

PATIENT-SPECIFIC ISSUES

Anticoagulant medications

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has published excellent guidelines for anticoagulant therapy. These are summarised in Table 28.2. In brief:

Table 28.2 The Amercian Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines on anticoagulants in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures

| Acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the anticoagulated patient: |

| Procedure risk | Condition risk for thromboembolism | |

| High | Low | |

| High | Discontinue warfarin 3–5 days before procedure | Discontinue warfarin 3–5 days before procedure |

| Consider heparin while INR is below therapeutic level | Reinstitute warfarin after procedure | |

| Low | No change in anticoagulation. Elective procedures should be delayed while INR is in supratherapeutic range | |

| Aspirin and other non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use | ||

| In the absence of a preexisting bleeding disorder, endoscopic procedures may be performed in patients taking aspirin or other NSAIDs | ||

INR = international normalised ratio.

From Gastrointest Endosc 1998;48:672–5, with permission.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

There is very little scientific evidence to guide practice. Excellent guidelines are available from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, which are summarised in Table 28.3. In brief, endoscopic procedures can be divided into high and low risk of significant bacteraemia and patient factors can similarly be classed in terms of risk from bacteremia. Low-risk procedures (such as gastroscopy and colonoscopy with or without polypectomy) never mandate the use of antibiotics, but they may be used at the clinician’s discretion. High-risk patients (e.g. those with prosthetic heart valves, previous endocarditis, recent vascular graft) undergoing a high-risk procedure (such as oesophageal dilation or sclerosis of varices) used to require antibiotics but this is not longer recommended routinely. All other permutations of patient and procedure are guided by physician preference. When there is doubt, most clinicians take a pragmatic approach and give prophylactic antibiotics.

Table 28.3 The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines on management of antibiotics in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures

| Patient condition | Procedure contemplated | Antibiotic prophylaxis |

| High risk: |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS-FNA = endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration; IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous.

From Hirota WK, Petersen K, Baron TH, et al. Guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 58:475–82, with permission.

SUMMARY

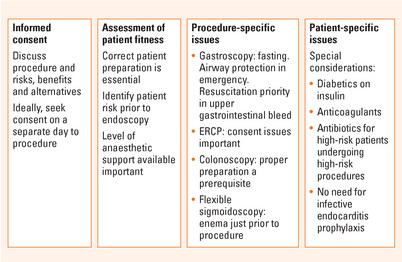

Correct patient preparation is essential for safe and effective endoscopic procedures (Figure 28.1).

The issues that have to be considered are:

Barkun A, Chiba N, Enns R, et al. Commonly used preparations for colonoscopy: efficacy, tolerability, and safety – A Canadian Association of Gastroenterology position paper. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:699-710.

Eisen GM, Baron TH, Domintz JA, et al. Guideline on the management of anti-coagulation and anti-platelet therapy for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:775-779.

Faigel DO, Eisen GM, Baron TH, et al. Preparation of patients for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:446-450.

Hirota WK, Petersen K, Baron TH, et al. Guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:475-482.

Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, et al. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909.

Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis. Guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007. April 19; [Epub ahead of print]

Zukerman MJ, Hirota WK, Adler DG, et al. The management of low-molecular weight heparin and nonaspirin antiplatelet agents for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:189-194.