Chapter 48 How Does Surgeon and Hospital Volume Affect Patient Outcome after Traumatic Injury?

For many orthopedic conditions, a clear association exists between patient outcome and the volume of similar cases treated by the hospital or surgeon providing care in Canada,1–4 the United States,5–12 and other countries.13–15 After traumatic injury, patient factors such as age, comorbidity, and the severity of injury are by far the most important determinants of mortality, although provider volume and availability of appropriate resources and care protocols do have an important influence on survival. For survivors of multisystem injuries, functional outcome is in large part determined by the residual impact of musculoskeletal and neurologic injuries. The experience and expertise of the hospital and the surgical team managing such injuries may well have a profound impact on the risk for complications, the rate of return to maximal function, the cost of care, and the ultimate functional outcome achieved. Provider experience may affect not only the excellence of procedural execution, but may be a factor at all stages of management, including preoperative decision making, the availability of optimal implants, monitoring equipment and support staff, and the adherence to optimized postoperative management protocols. Few studies have attempted to delineate the underlying mechanisms that might be driving the volume–outcome relation.2 Although the mechanism may be that high-volume providers have developed mature systems of care and expertise from exposure to a high volume of cases, there is also some evidence that vulnerable populations in the United States with elective conditions such as total knee replacement are preferentially selecting or being forced to select low-volume institutions.16 A similar finding was noted for patients with hip fracture.17

OPTIONS

The demonstration of a systematic variation in patient outcome should be followed by strategies to eliminate suboptimal results, thereby minimizing outcome variation near the high end of the scale. Strategies to achieve this fall into three categories: (1) mandating minimum provider volumes; (2) regionalizing care to specialized centers; and (3) trying to understand the internal mechanisms involved and providing support, education, and best practice advice to those with inferior results (regardless of whether that given provider is low or high volume). The problem with simply mandating a minimum volume for a provider is that there is no scientific evidence to support the existence of a threshold volume below which outcomes are likely to suffer.14,18 Furthermore, a given lowvolume provider might have excellent results, and a specific high-volume provider could have a high complication rate. Alternative strategies may include monitoring provider outcomes and following up on significant variances (in a negative or positive direction) to learn from good results and to work to improve poor results. Regionalization for specific conditions to specialized high-volume “centers of excellence” has been proposed for a number of conditions including trauma7 and total joint arthroplasty.19 Regionalization allows for a critical mass of specialists with access to specialized equipment, care protocols, and a variety of medical and support staff available to support the care of resource-intensive, specific conditions; but for co-mmon conditions that require no specialized staff or equipment, the inconvenience and expense of patient travel needs to be considered. If a volume–outcome relation were demonstrated for a less resource-intensive injury, an alternative strategy to regionalization for such conditions might involve linking low- and high-volume providers together to share in preoperative surgical decision making, provide advice regarding the development of care protocols for perioperative care, and to monitor the execution of surgery itself.

EVIDENCE

Specialized hospitals and surgeons have specific qualifications and interest in the subject of their subspecialty area. They also tend to be high-volume providers for the conditions of interest. Both specialized trauma providers and total joint arthroplasty centers have been studied.

Specialized Hospitals

In a Level I prospective cohort study, MacKenzie and colleagues7 compared patient outcomes for those treated in specialized trauma hospitals versus nontrauma hospitals. The most severely injured complex patients (with one or more system Abbreviated Injury Scale scores of 5 or 6) were significantly more likely to survive when treated in specialized trauma centers (RR of hospital death, 0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51–0.96). Young trauma victims younger than 55 years also had a lower in-hospital mortality rate when treated in specialized trauma centers (RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48–0.89). For older patients, the mortality rate was driven largely by comorbidity and age with less noticeable influence on risk for death for specialized versus nonspecialized trauma center care. These findings are consistent with data from the United Kingdom. Freeman and coauthors13 (Level II) note that the relation between volume and outcome for trauma centers in the United Kingdom was significant only for patients with complex multiple traumatic injuries; however, even the highest volume trauma hospital studied had volumes of only 96 patients per year, which is well below the volumes seen in many North American centers.7,11, 20

Specialized centers for total joint surgery have also been evaluated. Cram and coauthors19 (Level II) compared total joint replacement surgery in specialty and general hospitals using Medicare data from 1999 to 2003, which included 51,788 total hip and 99,765 total knee replacements. The profile of patients treated at specialized centers differed from that of general hospitals. Patients attending specialized centers tended to be from wealthier neighborhoods and had fewer comorbid conditions. After adjusting for patient comorbidity and hospital volume, the risk for adverse events was lower in specialty hospitals (odds ratio [OR], 0.64; 95% CI, 0.56–0.75) for primaries and much lower for more complex revision operations (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.36–0.66).

Specialized Surgeons

Haut and coworkers21 (Level II) compared the outcome for patients treated in the same center (Johns Hopkins) but by dedicated specialized trauma surgeons versus nonspecialist surgeons. The institutional protocols were the same regardless of which surgeon was on call. Despite this, the authors note a 50% increase in mortality rates for patients treated by nonspecialist surgeons in patients with severe injuries (Injury Severity Scale [ISS] > 15; OR of death, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.04–2.02) compared with specialized surgeons. Unexpected survivors were twice as common in the full-time trauma surgeon group (approximately 8 vs. 4 unexpected survivors per 1000 patients). Although surgeon factors certainly played a role in patient outcome, the largest driver of mortality was the severity of injury. Patients with an ISS greater than 15 were much less likely to survive regardless of surgeon specialization (OR, 36.8; 95% CI, 20.7–65.6). Severe head injury was the factor with the second greatest OR for risk for death (15.9; 95% CI, 10.1–25.2).

Provider Volume and Outcome

Shah and researchers8 (Level II) analyzed Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data for patients who underwent hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture. Volume quartiles were generated from the data, which included 173,508 patients. For hospitals, the lowest quartile treated fewer than 20 patients compared with more than 61 for the highest quartile, and for surgeons, the lowest quartile treated fewer than 4 patients compared with more than 11 for the highest quartile. Low-volume hospitals had a greater rate of complications including pulmonary embolus, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia, and a greater rate of prolonged length of stay beyond 10 days (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.46–1.66). Low-volume surgeons had a greater mortality rate (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.03–1.34) and a greater chance of prolonged (>10 days) length of stay (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.29–1.45).

Marcin and Romano22 (Level II) were interested to know whether volume changes over time within an institution might affect outcome. They studied only patient mortality and readmission rates for patients treated at designated trauma centers (Levels I-III). The authors did not compare results by trauma level designation. In contrast with other trauma studies that could not identify a significant association between mortality and provider volume in elderly patients,7 Marcin and Romano22 note lower mortality rates for patients older than 64 years treated in high-volume centers (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.71–0.87). They also note that for every 10 patients added to a particular institution’s monthly caseload, the odds of readmission for elderly patients older than 64 years increased (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01–1.21). The authors suggest that perhaps systems became overloaded, resulting in greater readmissions. These findings are in contrast with work by Hamilton and coworkers4 (Level II), who found that, for hip fractures, changing hospital volume over time had no effect on outcome. The authors suggest, therefore, that the observed volume–outcome relation between high- and low-volume institutions reflects differences in the quality of care between high- and low-volume hospitals, and not volume fluctuations per se.

The main outcomes reported for provider volume–outcome relations have included mortality and other complications, but there has been little information available regarding functional outcome. Katz and investigators5 (Level I) recently note that patients undergoing total joint replacement surgery who were treated by low-volume surgeons in low-volume hospitals were twice as likely to have a poor functional outcome score at 2 years compared with patients of high-volume surgeons in high-volume hospitals (OR of poor function, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.2). To the best of our knowledge, there are no reported studies of volume and functional outcome for patients with traumatic injuries.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Volume–outcome research has been criticized for incomplete consideration of confounding factors.18 Patient profile differs between high- and low-volume providers, making it difficult to adjust completely for differences in patient characteristics.16,17 This may account for the fact that fewer prospective studies were found to have a strong positive volume outcome relation compared with retrospective studies.23 Nonetheless, a randomized clinical trial allocating patients to low- or high-volume providers is unlikely ever to be conducted, and high-quality recent cohort studies have used innovative techniques to adjust for differences in patient case-mix across high- and low-volume providers.7,21

The identification of a volume–outcome relation is interesting, but much work needs to be done if patients are to benefit from these findings. Little information is available regarding the reasons for the observed better outcomes in higher volume or specialized centers.2 High-volume surgeons may be more enthusiastic about a procedure and have different indications24,25; however, there are no data available regarding how high- and low-volume providers make decisions regarding care, how the execution of surgery might differ, and how postoperative protocols might affect patient outcome. This information is necessary if we are to devise ways of using volume outcome information to improve care by educating low-volume providers.

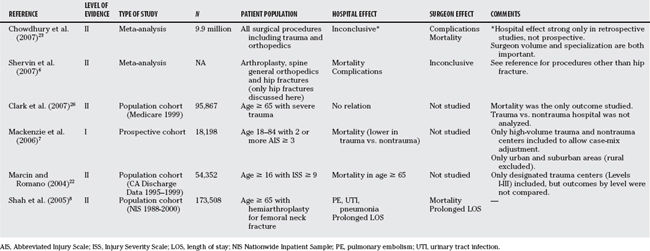

Clearly, much more work is needed to understand the mechanisms that underlie volume–outcome relations. Moreover, these mechanisms may differ for specific conditions, and work needs to be extended to include many other areas within orthopedics and traumatology (Table 48-1).

Table 48-2 provides a summary of recommendations.

| RECOMMENDATION | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Kreder HJ, et al. Provider volume and other predictors of outcome after total knee arthroplasty: A population study in Ontario. Can J Surg. 2003;46:15-22.

2 Liberman M, et al. The association between trauma system and trauma center components and outcome in a mature regionalized trauma system. Surgery. 2005;137:647-658.

3 Hamilton BH, Ho V. Does practice make perfect? Examining the relationship between hospital surgical volume and outcomes for hip fracture patients in Quebec. Med Care. 1998;36:892-903.

4 Hamilton BH, Hamilton VH. Estimating surgical volume— outcome relationships applying survival models: Accounting for frailty and hospital fixed effects. Health Econ. 1997;6:383-395.

5 Katz JN, et al. Association of hospital and surgeon procedure volume with patient-centered outcomes of total knee replacement in a population-based cohort of patients age 65 years and older. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:568-574.

6 Shervin N, Rubash HE, Katz JN. Orthopaedic procedure volume and patient outcomes: A systematic literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;457:35-41.

7 Mackenzie EJ, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:366-378.

8 Shah SN, Wainess RM, Karunakar MA. Hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture in the elderly surgeon and hospital volume-related outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:503-508.

9 Vitale MA, et al. The contribution of hospital volume, payer status, and other factors on the surgical outcomes of scoliosis patients: A review of 3,606 cases in the state of California. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:393-399.

10 Katz JN, et al. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and outcomes of total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1622-1629.

11 Nathens AB, et al. The effect of organized systems of trauma care on motor vehicle crash mortality. JAMA. 2000;283:1990-1994.

12 Kreder HJ, et al. Relationship between the volume of total hip replacements performed by providers and the rates of postoperative complications in the state of Washington. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:485-494.

13 Freeman J, Nicholl J, Turner J. Does size matter? The relationship between volume and outcome in the care of major trauma. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11:101-105.

14 Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:511-520.

15 Davoli M, et al. [Volume and health outcomes: An overview of systematic reviews]. Epidemiol Prev. 2005;29(suppl):3-63.

16 Losina E, et al. Neighborhoods matter: Use of hospitals with worse outcomes following total knee replacement by patients from vulnerable populations. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:182-187.

17 Liu JH, et al. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for complex surgery. JAMA. 2006;296:1973-1980.

18 Clark CR, Heckman JD. Volume versus outcomes in orthopaedic surgery: A proper perspective is paramount. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1619-1621.

19 Cram P, et al. A comparison of total hip and knee replacement in specialty and general hospitals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1675-1684.

20 Nathens AB, et al. Relationship between trauma center volume and outcomes. JAMA. 2001;285:1164-1171.

21 Haut ER, et al. Injured patients have lower mortality when treated by “full-time” trauma surgeons vs. surgeons who cover trauma “part-time.”. J Trauma. 2006;61:272-278.

22 Marcin JP, Romano PS. Impact of between-hospital volume and within-hospital volume on mortality and readmission rates for trauma patients in California. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1477-1483.

23 Chowdhury MM, Dagash H, Pierro A. A systematic review of the impact of volume of surgery and specialization on patient outcome. Br J Surg. 2007;94:145-161.

24 Dunn WR, et al. Variation in orthopaedic surgeons’ perceptions about the indications for rotator cuff surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1978-1984.

25 Marx RG, et al. Beliefs and attitudes of members of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons regarding the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:762-770.

26 Clark DE, et al. Initial presentation of older injured patients to high-volume hospitals is not associated with lower 30-day mortality in Medicare data. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1829-1836.