Chapter 30 How Do You Best Diagnose Septic Arthritis of the Hip?

The initial presentation of a child with an acutely irritable hip can pose a diagnostic challenge to the orthopedic surgeon, pediatrician, emergency department physician, or primary care physician. After ruling out the more apparent radiographic abnormalities of Legg–Perthes disease, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and fracture, the differential diagnosis commonly involves septic arthritis versus transient synovitis.

The differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children is essential because the two clinical entities have quite different treatments and potential for negative sequelae. Septic arthritis is treated with operative drainage and antibiotics, whereas transient synovitis is usually self-limited and treated symptomatically.1–7 Complications of septic arthritis include osteonecrosis, growth arrest, and sepsis, whereas transient synovitis usually has a benign clinical course.8–15 In addition, the early, accurate diagnosis of septic arthritis is essential because poor outcomes after septic hip in children have been associated with delay in diagnosis.16–20

OVERVIEW

Septic Arthritis

Septic arthritis of the hip in a child constitutes a surgical emergency. Prompt recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of this entity are essential. Bacterial infection of the joint space results in an inflammatory effusion consisting of up to 90% polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs).21 The release of proteolytic enzymes by PMNs and bacteria, in conjunction with increased intra-articular pressure, can result in rapid and irreversible hyaline cartilage degradation in as little as 6 hours. If unrecognized or left untreated, this process can result in joint destruction with subsequent severe deformity and devastating lifelong disability. Joint infections can ultimately lead to disseminated infection, systemic bacterial sepsis, multiorgan failure, and death. However, if recognized and treated in a timely fashion with surgical drainage and appropriate antimicrobial therapy, a good outcome with minimal sequelae can be expected. Poor outcomes are most closely associated with delay in diagnosis. Other factors related to poor outcome include patient age younger than 6 months, prematurity, Staphylococcus species infection, and concomitant osteomyelitis.

Septic arthritis may occur as a result of hematogenous seeding, local spread from a contiguous infection, or primary seeding of a joint secondary to surgery or trauma. In the hip, shoulder, ankle, and elbow (90% of cases), septic arthritis often develops after metaphyseal osteomyelitis with subperiosteal erosion, abscess formation, and subsequent joint communication (because of the intra-articular location of the metaphyses in these joints). Premature and immunocompromised children are at greater risk. The most commonly identified causative organisms are Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococci, Streptococcus pneumococcus, other gram-negative organisms (may be seen in special hosts or after trauma-klebsiellae, salmonellae, kingellae), and Neisseria gonorrhea.22 Before the advent of an effective vaccine, Haemophilus influenzae type B was responsible for up to 40% of cases but has largely disappeared because of successful immunization programs.23,24 In the neonate, group B b-hemolytic streptococcus and gram-negative bacilli are common causative agents in addition to S. aureus. Gram-negative infections are common among intravenous (IV) drug abusers. Mycobacteria and fungi must be considered in patients with chronic infection.

Diagnosis

Children with septic arthritis will often have a history of recent upper respiratory or local soft-tissue infection, as well a recent course of antibiotics. A high level of suspicion is important when evaluating premature and immunocompromised infants. Septic arthritis is more commonly seen in boys and is most common in children younger than 2 years. Patients may report pain, stiffness, and malaise, but such a history is often impossible to ascertain from small children or infants. Fever, limp, inability or refusal to weight bear, limited and painful range of motion (secondary to capsular stretching), erythema, warmth, tenderness, and swelling are common physical findings. The child may complain of anterior hip, groin, thigh, or knee pain. The child may lie with the hip in external rotation, adduction, and mild flexion to maximize joint volume and decrease capsular stretch. Physical examination of the infant can be challenging and may only demonstrate limited or a lack of active motion in the affected extremity (pseudoparalysis).

EVIDENCE

Imaging

Ultrasonography has been demonstrated good accuracy in detecting an effusion associated with septic arthritis of the hip in children. Zamzam25 retrospectively studied 81 children with septic arthritis and 73 children with transient synovitis, finding sensitivity of 86.4% and specificity of 89.7%. Dörr and colleagues26 also found ultrasound to be useful in detecting effusion in 204 acutely irritable hips. In addition, they found certain characteristics, such as synovial hypertrophy and capsular thickening, to be helpful in differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis. In a prospective analysis of 500 children with a painful hip or limp, Miralles and researchers27 found ultrasonography to be useful in the detection of effusion. In addition, these authors showed that transient synovitis had resolution of the effusion at repeat ultrasound 2 weeks later.

MRI has been shown to be useful in detecting associated osteomyelitis but may also be useful in differentiating septic arthritis from transient synovitis. In a retrospective case series of 49 children with transient synovitis and 18 children with septic arthritis, Yang and investigators28 found that patients with transient synovitis were more likely to have contralateral effusion and absence of signal intensity in the surrounding soft tissue and bone marrow.

Laboratory Tests

Clinicians have empirically utilized different labora-tory variables to help distinguish between septic arthritis and transient synovitis. Bennett and Namnyak29 emphasize leukocyte count in children older than 3 years. Morrey and coauthors20 and Klein and resear-chers21 accent increased ESR. Chen and colleagues30 found both leukocytosis and increased ESR to be common. However, because these retrospective case series of children with septic arthritis did not have a comparison group of children with transient synovitis, they were unable to identify differences between the groups and were unable to determine the diagnostic performance of assorted variables.

On comparing children with septic arthritis and transient synovitis in retrospective case series, poor diagnostic utility has been found for various screening clinical, laboratory, and radiographic data because of substantial overlap between the two groups. Molteni22 retrospectively reviewed 97 patients with so-called nonspecific arthritis and 37 patients with septic arthritis of various joints including the hip, knee, ankle elbow, and wrist. Diagnoses were established presumptively, with joint fluid analysis of 12 of 97 patients with nonspecific arthritis and of 32 of 37 patients with septic arthritis. Fifty percent of the patients with septic arthritis had negative cultures and joint fluid WBC count varied from 5 to 385 3 1000/mm3. Without statistically comparing the two groups, Molteni22 describes the clinical and laboratory findings in each (septic arthritis vs. nonspecific arthritis): age (5.8 vs. 6.0 years), male sex (22/37 vs. 49/97), temperature >101°F (82% vs. 38%), serum WBC count (7.23 vs. 6.3 × 1000/mm3), and ESR (50 vs. 35 mm/hr). Because of the similarities in values and the extent of overlap, he concludes that reliable data were not found to distinguish the two different joint processes. Del Beccaro and colleagues31 also found that overlap between screening variables impeded the differentiation of septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children. They compare 94 children with transient synovitis (defined retrospectively via clinical course) with 38 patients with septic arthritis (defined as pyarthrosis). In the transient synovitis group, 21 of 94 patients had joint fluid analysis, and in the septic arthritis group, 28 of 38 patients had joint fluid cell counts. They found significant (P < 0.05) univariate differences between the two groups with respect to the following factors (septic arthritis vs. transient synovitis): temperature (38.1°C vs. 37.2°C), ESR (44 vs. 19 mm/hr), PMN (7.8 vs. 6.3 × 1000/mm3), and bands (903 vs. 295/mm3). Of note, with the numbers available for study, serum WBC count could not be shown to differ significantly (P > 0.05) (13.2 vs 11.2 × 1000/mm3). Although ESR was significantly (P < 0.05) different between the two groups, the substantial amount of overlap made it a poor discriminator. The range of ESR for the septic hip group was 6 to 90 mm/hr (with 24% of patients with ESR <20 mm/hr), and the range for the synovitis group was 1 to 125 mm/hr (with 28% of patients with ESR >20 mm/hr). By combining ESR >20 mm/hr with temperature >37.5°C, they were able to identify 97% of the septic arthritis cases; however, those parameters also included 47% of the transient synovitis cases. Kunnamo and coworkers32 reviewed 278 children younger than 16 years with various arthritides, including transient synovitis, juvenile arthritis, septic arthritis, serum sickness, enteroarthritis, and Schonlein–Henoch purpura. They found the patients with septic arthritis (n = 18) to differ significantly (P < 0.05) from the other patients with respect to CRP level, temperature >38.5°C, and serum WBC count >12 (×1000/mm3).20 Levine and colleagues33 emphasize the value of CRP in the diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip. In a retrospective review of 133 children with an irritable joint, CRP level had better predictive ability than ESR. In particular, if the CRP level was less than 1.0 mg/dL, the probability that the patient did not have septic arthritis was 87%.

Prediction Rules

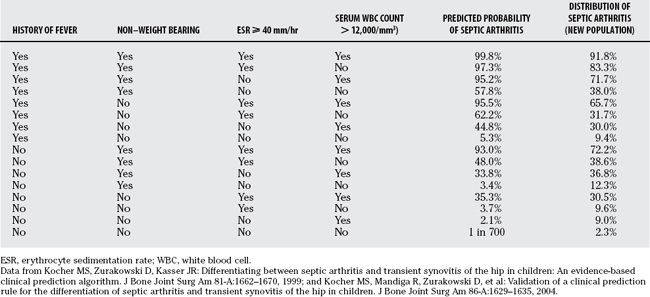

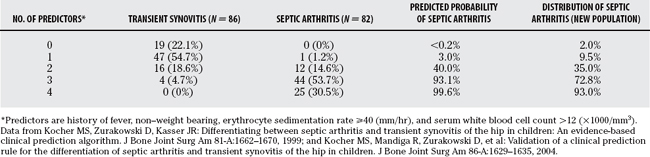

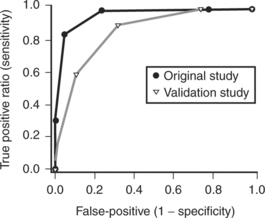

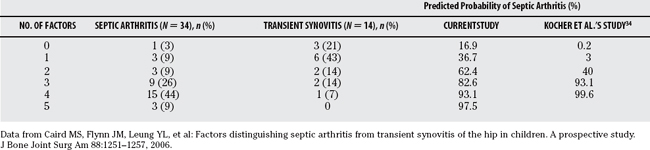

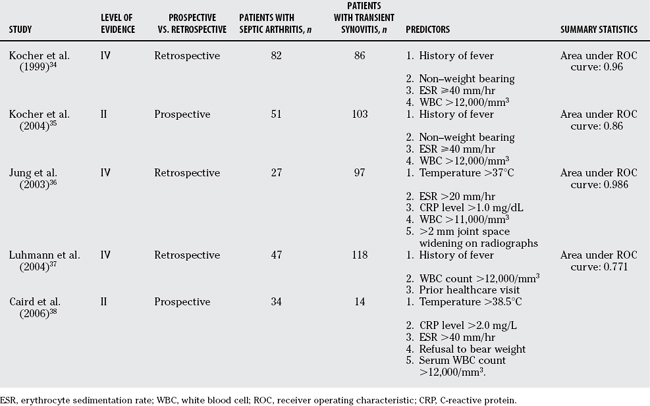

Prediction rules based on presenting variables have been developed to differentiate septic arthritis from transient synovitis of the hip. Kocher and reviewers34 retrospectively analyzed 82 children with septic arthritis and 86 children with transient synovitis of the hip treated at Children’s Hospital Boston from 1979 to 1996. Diagnoses of true septic arthritis, presumed septic arthritis, and transient synovitis were made based on joint fluid WBC, blood and joint fluid cultures, and clinical course. Using multivariate analysis, they identified four independent predictors of septic arthritis (history of fever, non–weight bearing, ESR ⩾40 mm/hr, and serum WBC >12,000/mm3). The predicted probability of septic arthritis was calculated for all 16 combinations of these 4 predictors (Table 30-1) and was summarized as 0.2% for 0 predictor, 3.0% for 1 predictor, 40.0% for 2 predictors, 93.1% for 3 predictors, and 99.6% for 4 predictors (Table 30-2). This prediction rule demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.96 (Fig. 30-1).

These authors then validated this prediction rule in a new series of patients.35 They prospectively analyzed 51 children with septic arthritis of the hip and 103 children with transient synovitis of the hip treated at Children’s Hospital Boston from 1997 to 2002. Using the same diagnostic parameters and similar analysis, they identified the same four multivariate predictors of septic arthritis (history of fever, non–weight bearing, ESR ≤ 40mm/hr, and serum WBC 12,000/mm3). The predicted probability of septic arthritis demonstrated similar but not identical values (see Table 30-1) and was summarized as 2.0% for one predictor, 9.5% for one predictor, 35.0% for 2 predictors, 72.8% for 3 predictors, and 93.0% for 4 predictors (see Table 30-2). The diagnostic accuracy showed diminished but still good performance with an area under the ROC curve of 0.86.

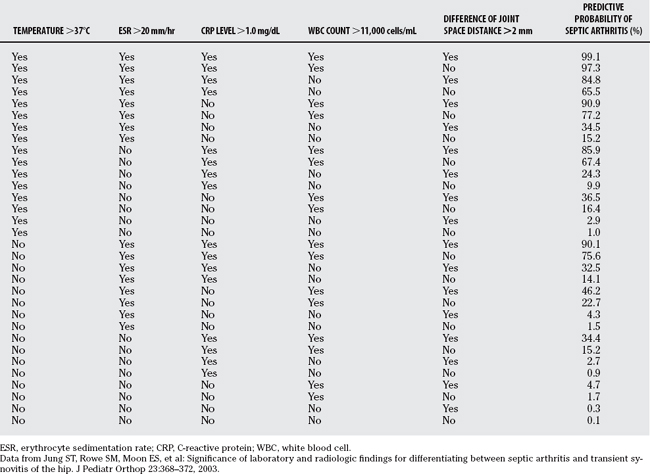

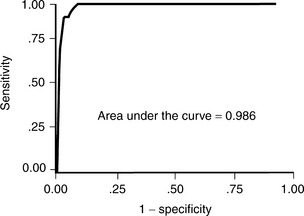

Jung and colleagues36 performed a similar study to establish a prediction rule for the differentiation of septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip (Fig. 30-2). In a retrospective series of 97 children with transient synovitis of the hip and 27 children with septic arthritis of the hip, they identified five independent multivariate predictors of septic arthritis: temperature >37°C, ESR >20 mm/hr, CRP level >1.0 mg/dL, serum WBC count >11,000/mm3, and >2 mm joint space difference on radiographs. Four of these five predictors were similar to those of Kocher and reviewers.34 They developed an algorithm based on the 32 combinations of the 5 predictors. The area under the ROC curve for their prediction rule was 0.986 (Table 30-3). This prediction rule has not been validated in a new patient population.

FIGURE 30-2 Receiver-operating characteristic curve for clinical prediction rule of Jung and colleagues.36

(Data from Jung ST, Rowe SM, Moon ES, et al: Significance of laboratory and radiologic findings for differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop 23:368-372, 2003.)

Luhmann and coworkers37 developed a new clinical prediction rule and analyzed the performance of the prediction rule of Kocher and reviewers34 in a retrospective series of 47 septic hips and 118 transient synovitis hips at St. Louis Children’s Hospital from 1992 to 2000. Their multivariate model identified three predictors of septic arthritis: history of fever, serum WBC >12,000/mm3, and prior healthcare visit. Two of the four predictors from the algorithm of Kocher and reviewers34 were not predictive in their model: ESR and non–weight bearing. The area under the ROC curve for their model was 77.1%, and the area under the ROC curve for the algorithm of Kocher and reviewers34 in their population was 79.9%.

Caird and researchers38 also developed a prediction rule for the differentiation of children with septic arthritis versus transient synovitis of the hip. In a prospective study of 53 children who underwent aspiration for an acutely irritable hip over a 4-year period at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, they identified 5 predictors of septic arthritis: fever >38.5°C, CRP level >2.0 mg/L, ESR >40 mm/hr, refusal to bear weight, and serum WBC >12,000/mm3. The four predictors from the algorithm of Kocher and reviewers34 were predictive in this model, and CRP level showed enhanced diagnostic performance over ESR. The probability of septic arthritis was 16.9% for 0 predictors, 36.7% for 1 predictor, 62.4% for 2 predictors, 82.6% for 3 predictors, 93.1% for 4 predictors, and 97.5% for 5 predictors (Table 30-4).

Clinical Practice Guidelines

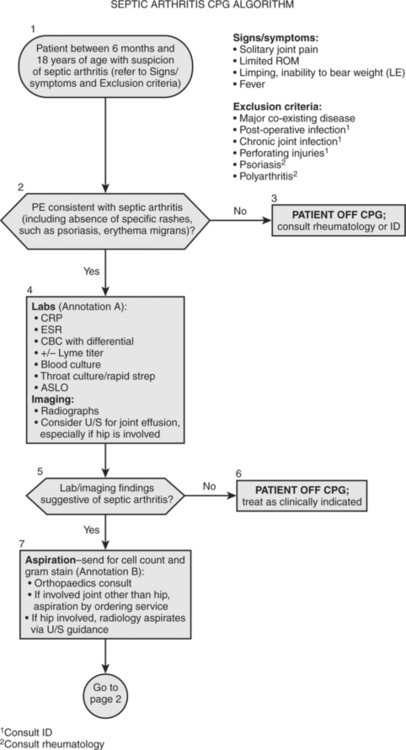

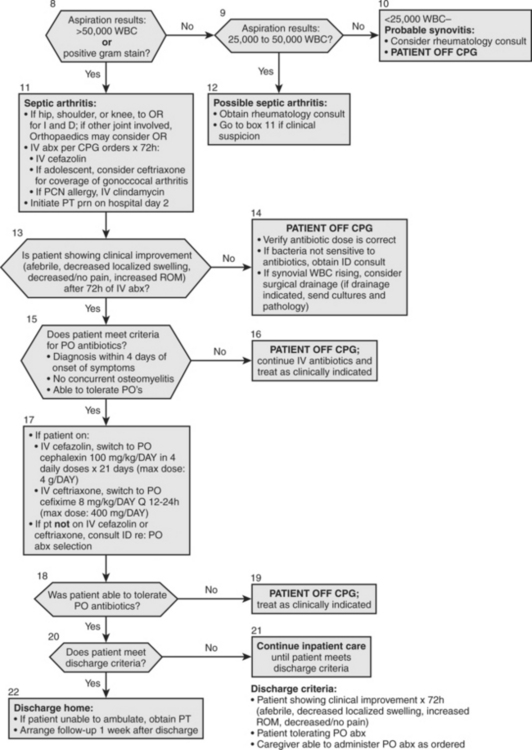

Kocher and coworkers39 developed a clinical practice guideline (CPG) for the diagnosis and management of patients with septic arthritis of the hip (Fig. 30-3). The diagnostic arm of the algorithm included laboratory analysis of CRP level, ESR, CBC count with differential, Lyme titer, blood culture, throat culture, and antistreptolysin O titer (ALSO). The imaging arm of the algorithm included radiographs and ultrasound. In a case–control study of the performance of this algorithm, the authors found that CPG patients had significantly greater rates of obtaining initial and follow-up CRP tests (93% vs. 13% and 70% vs. 7%), lower use of initial bone scan (13% vs. 40%), lower rates of presumptive drainage (13% vs. 47%), greater compliance with recommended antibiotic therapy (93% vs. 7%), faster change to oral antibiotics (3.9 vs. 6.9 days), and shorter hospital course (4.8 vs. 8.3 days). No significant differences were found for outcome variables of readmission, recurrent infection, recurrent drainage, development of osteomyelitis, septic osteonecrosis, or limitation of motion. They conclude that patients on the septic arthritis CPG had less variation of process and improved efficiency of care, without a significant difference in outcome.

FIGURE 30-3 Clinical practice guideline for septic arthritis.

(Adapted from Kocher MS, Mandiga R, Murphy J, et al: A clinical practice guideline for septic arthritis in children: Effi cacy on process and outcome for septic arthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A:994-999, 2003, with permission of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.)

Certain presenting variables can be useful in the diagnosis of septic arthritis. Based on history, a history of fever and of non–weight bearing have been identified as predictors of septic arthritis. Based on laboratory tests, increased serum WBC count, ESR, and CRP level are predictive of septic arthritis. In particular, CRP level has greater diagnostic value than ESR. Based on imaging, ultrasonography can identify an effusion and can help guide arthrocentesis (Table 30-5).

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Adams JA. Transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Bone Joint Surg. 1963;45B:471-476.

2 Dan M. Septic arthritis in young infants: Clinical and microbiologic correlations and therapeutic implications. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:147-155.

3 Edwards EG. Transient synovitis of the hip joint in children. JAMA. 1952;148:30-36.

4 Haueisen DC, Weiner DS, Weiner SD. The characterization of transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1986;6:11-17.

5 Petersen S, Knudsen FU, Andersen EA, Egeblad M. Acute haematogenous osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in childhood: A 10-year review and follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51:451-457.

6 Sharwood PF. The irritable hip syndrome in children. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52:633-638.

7 Wingstrand H. Transient synovitis of the hip in the child. Acta Orthop Scand. 1986;57(supp):1-61.

8 Betz RR, Cooperman DR, Wopperer JM, et al. Late sequelae of septic arthritis of the hip in infancy and childhood. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:365-372.

9 De Valderrama JAF. The “observation hip” and its late sequelae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1963;45:462-470.

10 Hermel MB, Albert SM. Transient synovitis of the hip. Clin Orthop. 1962;22:21-26.

11 Hunka L, Said SE, MacKenzie DA, et al. Classification and surgical management of the severe sequelae of septic hips in children. Clin Orthop. 1982;171:30-36.

12 Jacobs BW. Synovitis of the hip in children and its significance. Pediatrics. 1971;47:558-566.

13 Nachemson A, Scheller S. A clinical and radiological follow-up study of transient synovitis of the hip. Acta Orthop Scand. 1969;40:479-500.

14 Spock A. Transient synovitis of the hip in children. Pediatrics. 1959;24:1042-1048.

15 Wopperer JM, White JJ, Gillespie R, Obletz BE. Long-term follow-up of infantile hip sepsis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8:322-325.

16 Fabry G, Meire E. Septic arthritis of the hip in children: Poor results after late and inadequate treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983;3:461-466.

17 Gillespie R. Septic arthritis of childhood. Clin Orthop. 1973;96:152-159.

18 Jackson MA, Nelson JD. Etiology and medical management of acute suppurative bone and joint infections in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 1982;2:313-323.

19 Lunseth PA, Heiple KG. Prognosis in septic arthritis of the hip in children. Clin Orthop. 1979;139:81-85.

20 Morrey BF, Bianco AJJr, Rhodes KH. Septic arthritis in children. Orthop Clin North Am. 1975;6:923-934.

21 Klein DM, Barbera C, Gray ST, et al. Sensitivity of objective parameters in the diagnosis of pediatric septic hips. Clin Orthop. 1997;338:153-159.

22 Molteni RA. The differential diagnosis of benign and septic joint disease in children. Clin Pediatr. 1978;17:19-23.

23 Howard AW, Viskontas D, Sabbagh C. Reduction in osteomyelitis and septic arthritis related to Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccination. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19:705-709.

24 Peltola H, Kallio MJ, Unkila-Kallio L. Reduced incidence of septic arthritis in children by Haemophilus influenzae type-b vaccination. Implications for treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:471-473.

25 Zamzam MM. The role of ultrasound in differentiating septic arthritis from transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;15:418-422.

26 Dörr U, Zieger M, Hauke H. Ultrasonography of the painful hip. Prospective studies in 204 patients. Pediatr Radiol. 1988;19:36-40.

27 Miralles M, Gonzalez G, Pulpeiro JR, et al. Sonography of the painful hip in children: 500 consecutive cases. Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:579-582.

28 Yang WJ, Im SA, Lim GY, et al. MR imaging of transient synovitis: Differentiation from septic arthritis. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:1154-1158.

29 Bennett OM, Namnyak SS. Acute septic arthritis of the hip joint in infancy and childhood. Clin Orthop. 1992;281:123-132.

30 Chen CH, Lee ZL, Yang WE, et al. Acute septic arthritis of the hip in children: Clinical analysis of 31 cases. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1993;16:239-245.

31 Del Beccaro MA, Champoux AN, Bockers T, Mendelman PM. Septic arthritis versus transient synovitis of the hip: The value of screening laboratory tests. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1418-1422.

32 Kunnamo I, Kallio P, Pelkonen P, Hovi T. Clinical signs and laboratory tests in the differential diagnosis of arthritis in children. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141:34-40.

33 Levine MJ, McGuire KJ, McGowan KL, et al. Assessment of the test characteristics of C-reactive protein for septic arthritis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:373-377.

34 Kocher MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children: An evidence-based clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81-A:1662-1670.

35 Kocher MS, Mandiga R, Zurakowski D, et al. Validation of a clinical prediction rule for the differentiation of septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1629-1635.

36 Jung ST, Rowe SM, Moon ES, et al. Significance of laboratory and radiologic findings for differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:368-372.

37 Luhmann SJ, Jones A, Schootman M, et al. Differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children with clinical prediction algorithms. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:956-962.

38 Caird MS, Flynn JM, Leung YL, et al. Factors distinguishing septic arthritis from transient synovitis of the hip in children. A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1251-1257.

39 Kocher MS, Mandiga R, Murphy J, et al. A clinical practice guideline for septic arthritis in children: Efficacy on process and outcome for septic arthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:994-999.