4 How cancer is diagnosed and the impact of diagnosis

How cancer is investigated

http://www.rcr.ac.uk/content.aspx?PageID=323 (accessed May 2011).

How cancers are classified and staged

Classification

The results from the investigations may help to establish the type, position, size, grade and stage of the cancer. These will all be used to ensure an appropriate treatment is selected, along with a thorough assessment of the patient (this is discussed in Ch. 5). It is very important that the right words are used to describe all aspects of the cancer so that healthcare professionals are aware of the situation and the patient is not confused with too many different medical terms.

The word tumour is often used and, although it means ‘lump’, it is an ambiguous term and can mean either benign or malignant. This can confuse patients. If they are told they have a tumour, they may assume that they have a benign condition, when they actually have a malignant cancer. Although benign tumours can cause problems due to their size; be painful or unsightly; press on other body organs; take up space inside the skull (for example, like a brain tumour); and release hormones that affect how the body works, they are not cancers. Cancers are made up of malignant cells which are discussed in Chapter 2, so it is best to avoid the use of the word ‘tumour’, and use the word ‘cancer’ so that patients do not become confused. The main differences between benign and malignant tumours are given in Table 4.1.

| Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|

| Slow growing | Usually faster growing |

| Encapsulated | Irregular in shape |

| Cells appear normal under the microscope | Spreads locally and destroys the surrounding tissues |

| Does not spread to other parts of the body | Spreads to other parts of the body |

The specific names of tumours (both benign and malignant) are also made up of the specific tissue in the body (Table 4.2). So a benign, non-malignant tumour in the unstriated smooth muscle would be called a ‘leio-my-oma’ and a malignant cancerous tumour in the unstriated smooth muscle would be a ‘leio-myo-sarc-oma’. There are some exceptions to this rule. For instance, using the rules above, melanoma and lymphoma sound like they are benign tumours when in fact they are malignant.

| Adeno- | Glandular tissue |

| Haemo- | Blood |

| Angio- | Vessels |

| Lipo- | Fat |

| Osteo- | Bone |

| Myo- | Muscle |

| Rhabdo- | Striated muscle |

| Leio- | Unstriated (smooth) muscle |

| Chondro- | Cartilage |

| Endo- | Lining |

Staging

To ascertain the extent that the cancer has grown, many cancers are staged using the TNM classification (Sobin et al 2010). This divides cancers into groups to provide a precise description:

• Tumour (T): identifies the primary tumour, size and infiltration.

• Node (N): identifies lymph node involvement.

• Metastatic (M): represents presence or absence of distant metastases.

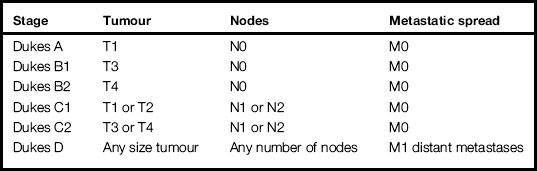

There are other methods of staging cancers. For example, Table 4.3 outlines Dukes staging of colorectal cancer (Dukes 1932).

Grading

Grading refers to how mutated the cells have become. The more a cell mutates, the more it may lose all resemblance to the normal tissue from which it arises. Grading is based on the appearance of the cancer under the microscope. Sometimes it is impossible to tell what type of cell a mutated cell was originally, and this leads to the diagnosis of unknown primary. The extent to which a cancer resembles the normal tissue is known as the degree of differentiation (Table 4.4).

| Well differentiated | Grade I Resembles normal cell – low grade |

| Moderately differentiated | Grade II Some similarities to normal cell |

| Poorly differentiated | Grade III Very immature, little resemblance to normal cell |

| Undifferentiated (anaplastic/dedifferentiated) | Grade IV No resemblance to original tissue – high grade |

The differentiation or grade provides some indication of how mutated the cells look and how similar they are in terms of function compared to the normal cells. This is clinically helpful to predict prognosis. For example, when staging breast cancer, the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) is often used (Haybrittle, Blamey and Elston 1982). This is a formula which gives an indication of how successful treatment might be, by considering the size of the cancer, whether or not the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes under the arm (and, if so, how many nodes are affected) and the grade of the cancer.

The formula is: NPI = (0.2 × cancer diameter in cm) + lymph node stage + cancer grade.

Applying the formula gives scores which fall into three bands:

1. Less than 3.4 suggests a good outcome with a high chance of a cure.

2. 3.4–5.4 suggests an intermediate level with a moderate chance of a cure.

3. More than 5.4 suggests a worse outlook with less chance of a cure.

The staging and grading information will be discussed at a multiprofessional meeting where all possible treatment options will be identified. All the possible options will be explained to the patient to help them decide which treatment to undergo. Chapter 8 outlines different treatment options and explores why one treatment might be chosen over another.

The impact of a cancer diagnosis

The East Midlands Cancer Network (2010) outlines ‘eleven well recognised steps to breaking bad news’ in their nationally recognised guidelines (Box 4.1)

Box 4.1 The East Midlands Cancer Network (2010) guidelines for communicating bad news with patients and their families

Step one – preparation and scene setting

Step one – preparation and scene setting

Step two – what does the patient know?

Step two – what does the patient know?

Step three – is more information wanted at that time?

Step three – is more information wanted at that time?

Step four – give a warning shot

Step four – give a warning shot

Step five – allow patient to decline information at this time

Step five – allow patient to decline information at this time

Step six – explain (if requested)

Step six – explain (if requested)

Step seven – elicit and listen to concerns

Step seven – elicit and listen to concerns

Step eight – encourage ventilation of feeling

Step eight – encourage ventilation of feeling

http://www.patient-experience.com/index.php/diagnosis-of-breast-cancer-blog/ (accessed November 2011).

http://www.healthtalkonline.org/Cancer/ (accessed November 2011).

Read Thain and Palmer (2010) (see References) to explore some of the techniques and strategies to minimise shock and distress (for example ‘the SPIKES protocol).

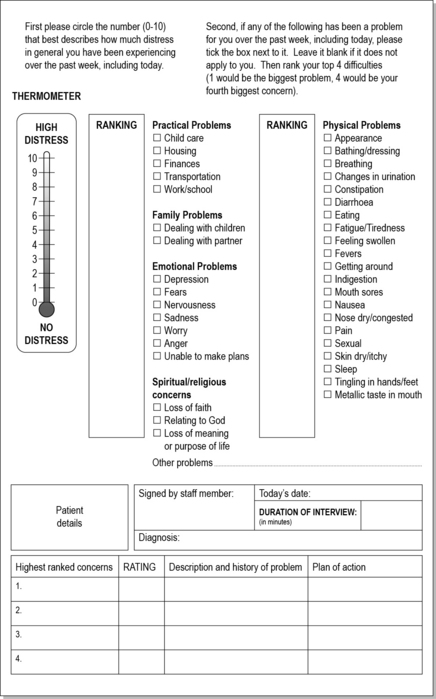

It is vital that the individual knows who they can contact and talk to regarding their anxieties and questions. Many clinical areas use an assessment tool such as the ‘distress thermometer’ (Fig. 4.1) to help patients and healthcare professionals identify specific issues patients might be experiencing. Assessment tools like this one are quick and easy to use, allowing the patient to identify any problems (physical, social, economic or psychological) they may be experiencing. Once patients and healthcare professionals have recognised the patients’ problems, then something can be done to support them. This doesn’t mean to say healthcare professionals have ‘all the answers’ as often there are not any definitive answers and we can’t always ‘solve the situation’. Often it is enough to sit with the patient and family and listen to their concerns: some situations may require the healthcare professional to provide information; other situations may require the healthcare professional to offer direct help; still other situations may require a referral to other health professionals or other agencies (support groups/charities) for specialised intervention/care/support. This type of assessment and intervention is covered in Section 2 where aspects of a cancer patient’s experience are explored.

Dukes C.E. The classification of cancer of the rectum. Journal of pathological bacteriology. 1932;35:323.

East Midlands Cancer Network. The guidelines for communicating bad news with patients and their families: significant news. Online. Available at: http://www.eastmidlandscancernetwork.nhs.uk/Library/BreakingBadNewsGuidelines.pdf, 2010. (accessed May 2011)

Haybrittle J.L., Blamey R.W., Elston C.W. A prognostic index in primary breast cancer. British Journal of cancer. 1982;45(3):361–366.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: distress management. Online. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp, 2007. (accessed November 2011)

Roth A.J., Kornblith A.B., Batel-Copel L., et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82:1904–1908.

Sobin L.H., Gospodarowicz M.K., Wittekind C.H. TNM classification of malignant tumours, 7th ed., New York: Wiley–Liss, 2010.

Thain C., Palmer C. Strategies to ensure effective and empathetic delivery of bad news. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2010;9(9):24–27.

Bultz B.C., Carlson L.E. Emotional distress: the sixth vital sign in cancer care. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2005;23(26):6440–6441.

Campbell J. Understanding social support for patients with cancer. Nurs. Times. 2007;103(23):28–29.

Edwards B., Clarke V. The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis on families: the influence of family functioning and patients’ illness characteristics on depression and anxiety. Psychooncology. 2004;13(8):562–576.

Pitceathly C., Maguire P. The psychological impact of cancer on patients’ partners and other key relatives: a review. Eur. J. Cancer. 2004;39(11):1517–1524.

Ryan H., Schofield P., Cockburn J., et al. How to recognize and manage psychological distress in cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.). 2005;14:7–15.

Saaegrov S., Haling A. What is it like living with a diagnosis of cancer? Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.). 2004;13:145–153.

Stringer S. Psychosocial impact of cancer. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2008;7(7):32–34. 37

Macmillan patient information, http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Home.aspx (accessed May 2011).

Royal College of Radiologists patient information, http://www.rcr.ac.uk/content.aspx?PageID=323 (accessed May 2011).

The Patient Experience Website, http://www.patient-experience.com/index.php/diagnosis-of-breast-cancer-blog/ (accessed July 2011).