Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Aetiology

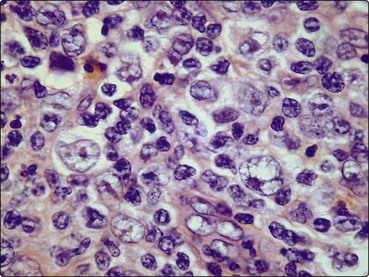

Hodgkin’s lymphoma is an unusual malignancy in that the malignant cells, termed Reed–Sternberg cells (Fig 29.1), and mononuclear Hodgkin’s cells form only a minority of the tumour. The remainder is composed of very variable numbers of other cells including lymphocytes, granulocytes, fibroblasts and plasma cells. This inflammatory cell infiltrate presumably reflects an immune response by the host against the malignant cells. Reed–Sternberg (RS) cells appear to originate from germinal-centre B-lymphocytes. In classical HL the RS cells are ‘crippled’ germinal-centre B-cells incapable of secreting immunoglobulins, while in lymphocyte predominant nodular HL RS cells the coding regions of the immunoglobulin genes are intact and potentially functional.

Classification

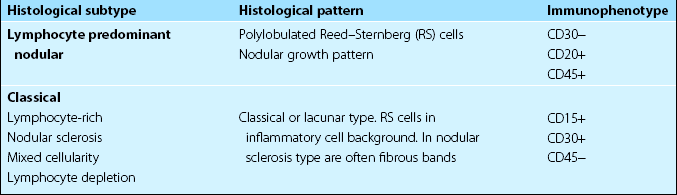

It is acknowledged in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification (see also p. 60) that ‘Hodgkin’s disease’ comprises two distinct ‘Hodgkin’s lymphomas’ with different clinical features: classical HL and lymphocyte predominant nodular HL (Table 29.1).

Clinical presentation

Asymmetrical and painless lymphadenopathy, most often in the cervical region, is the most common presentation. The nodes usually gradually enlarge but may fluctuate in size. Patterns of disease suggest contiguous spread via the lymphatic chain. Mediastinal involvement is a particular feature of the nodular sclerosing histological subtype (Fig 29.2). Splenomegaly and hepatomegaly occur but massive enlargement is rare.

Diagnosis and staging

Staging

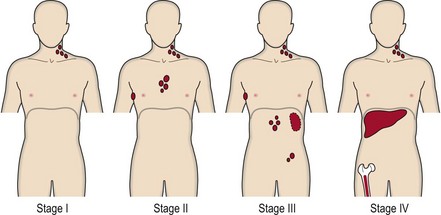

Optimal treatment is determined by the stage of disease (Fig 29.3), which is derived from the following investigations:

Fig 29.3 Staging of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Stage I, node involvement in single lymph node area (e.g. cervical); II, two or more lymph node areas on one side of diaphragm; III, nodal involvement above and below diaphragm; IV, involvement outside node areas (e.g. liver, bone marrow). The stage is followed by the letter A (absence) or B (presence) pertaining to significant systemic symptoms (one or more of: unexplained fever above 38°C, night sweats, loss of more than 10% body weight in 6 months). A single extranodal site is designated E.

1. Blood count and bone marrow investigation. A mild normochromic or microcytic anaemia and blood eosinophilia may be present. Bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy to detect infiltration by disease is necessary in more advanced cases.

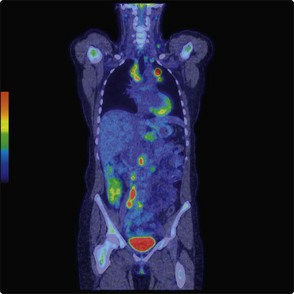

2. Imaging. A whole body computed tomography (CT) scan is the central staging procedure. In difficult cases this may be supplemented by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Positron emission topography (PET) scanning is increasingly used in staging and also to assess response during and after treatment (Fig 29.4). Clinical trials are needed to better define its role.

Management of classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Early stage disease

Patients with stage I or II disease who lack adverse features (Table 29.2) have been traditionally treated with radiotherapy alone. This is given over an extended field using a linear accelerator. Nodes above the diaphragm are treated using the ‘mantle’ field (like the mantle on a suit of armour) while the ‘inverted Y’ field includes all nodes below the diaphragm.

Table 29.2

Prognosis and late effects of treatment

Survival rates are closely linked to stage although within each stage other prognostic factors influence outcome (see Table 29.2). Cure rates for early stage disease are around 90% while even more advanced disease is curable in up to 80% of patients with optimal management. As in other haematological malignancies, elderly patients tolerate chemotherapy less well and cure rates are more modest. In long-term survivors there is a risk of secondary malignancy. Young women receiving mediastinal irradiation are at particularly high risk of breast cancer. Other possible late effects of treatment include cardiac disease, lung damage, sterility and endocrine dysfunction.