chapter 60 HIV management in general practice

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Globally, in 2007, it was estimated that 30–36 million people were living with HIV infection, with a death toll to that point of 1.8–2.3 million.1

How many HIV-infected patients are managed in general practice? The BEACH study in Australia counted 80 consultations per 100,000 and this low figure would probably be seen in other similar developed countries, where it is a predominantly gay male population that is affected.3

In resource-poor communities where there are limited antiviral agents available there will be a higher involvement of primary care / general practice and more reliance on traditional healing and so on. However, even here the number of people with HIV who are taking antiviral medications is growing, with the primary care being delivered in a variety of ways.4

In resource-rich communities there is greater complexity of choices and an interest in complementary/integrative measures. Here there will be more centralisation of care to specialist doctors and clinics. Yet even so there is a large burden of poverty within the HIV-affected community and consequent difficulties in gaining access to best care.5

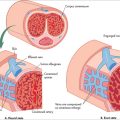

HIV AND THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

PRIMARY PREVENTION IN GENERAL PRACTICE

SECONDARY PREVENTION

TERTIARY PREVENTION

Once the patient is known to have HIV infection, the role of the GP may include:

BOX 60.3 Broad principles of HIV treatment

Source: ASHM 20098

COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among HIV-positive people is widespread. On average, some 60% use CAM to treat HIV-related concerns.10 However, this proportion differs markedly from study to study.11 This is despite the effectiveness of current antiretroviral therapies, and despite the potential for certain types of CAM to compromise those therapies.10,12,13 Some studies suggest that those people who are more likely to use CAM are also more likely to refuse anti-retroviral therapies.11

Published research suggests that those who are more likely to use CAM are Caucasian, men who have sex with men, more educated and of higher income.10 They are also more likely to have AIDS (than just HIV infection), to have symptoms related to HIV (and those symptoms to be more severe) and to have longer disease duration and a higher degree of disability.10

It is not surprising therefore that the reason for CAM use is more often to relieve symptoms and alleviate side effects of treatment, thereby improving quality of life.10

The types of CAM used are varied—Table 60.1 lists rates of use for various types of CAM.

| Type of CAM | % using |

|---|---|

| Drug or diet therapies | 71 |

| Psycho-spiritual therapies | 66 |

| Meditation | 54 |

| Massage | 39 |

| Herbs | 34 |

| Faith healing | 33 |

| Megavitamins* | 28 |

| Chiropractor | 25 |

| Visualisation | 24 |

* The most frequently reported of these have been vitamin C, vitamin E, garlic and multiple vitamin and mineral supplements.12

Source: Bormann et al 200911

Reviews of the evidence supporting CAM have pointed to methodological flaws and limited trial numbers and therefore lack of evidence for efficacy. However, stress management did appear to increase quality of life.14

There are other particular recommendations regarding optimising immune health, which include aspects of stress management, diet and supplements. However, data on the efficacy of herbal medicines has been assessed as insufficient to make firm recommendations.15

MIND–BODY

HIV progression to AIDS and speed of AIDS progression has been consistently linked with a range of psychosocial factors. For example, a study controlling for a range of relevant variables, including treatment, showed that increased stressful life events, coping by means of denial, low social support and high serum cortisol (a marker of chronic stress) significantly predicted disease progression.16 The increased risk for progression from HIV to AIDS was two to three times at 5 years follow-up.17 The high cortisol levels associated with chronic stress are also found to be associated with low white cell count and higher dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) concentrations, both markers of poor prognosis.18 Other studies have also confirmed the findings of social isolation and pessimism being poor prognostic factors19 and ‘active confrontational coping style’ being associated with better prognosis, probably because of both improved compliance and immunological mechanisms described by psychoneuroimmunology.20 Promising findings from a randomised controlled trial also suggest that reducing stress through cognitive-behavioural stress management, relaxation training and increasing social support is associated with reduced anxiety. This finding corresponded with changes in important physiological markers such as reduced catechol output, increased white cell counts,21 reduced cortisol, DHEA-S and herpes simplex virus type 2 antibody titres (a common infection in gay men).22 In another arm of the same study it was also found that the relaxation training on its own was associated with reductions in cortisol levels, depending on the level of compliance.23 This research has now gone further to demonstrate that mind–body interventions like mindfulness meditation can buffer CD4+ T-lymphocyte decline in HIV-1 infected adults.24 Religious coping and religious behaviour (church attendance, prayer, spiritual discussion, reading religious literature) have also been found to be associated with reduced scores for depression and better immune parameters such as higher white cell count, independent of symptom status.25,26

Australian Government, Health Insite, Complementary medicines. http://www.healthinsite.gov.au/topics/Complementary_Medicines.

National Association of People Living with HIV/AIDS. http://www.napwa.org.au.

National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (US). http://www.nccam.nih.gov.

1 UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Executive summary. Online. Available at: unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008, 2008.

2 UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Ch 4: Preventing new HIV infections: the key to reversing the epidemic. Online. Available at unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008, 2008.

3 Fahridin S, Miller G. Management of HIV/AIDS. Aust Family Physician. 2009;38(8):573.

4 UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Ch 5: Treatment and care; 2008. Online. Available: http://unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008.

5 Grierson J, Thorpe R, Pitts M. HIV futures five. The Living with HIV Program at the Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society. Melbourne: La Trobe University; 2006. Online. Available: http://www.latrobe.edu.au/hiv-futures/.

6 Australasian Society for HIV Medicine. HIV, viral hepatitis and STIs: a guide for primary care. Darlinghurst, New South Wales: ASHM, 2008.

7 Hassed C. The essence of health. The seven pillars of wellbeing. Sydney: Ebury Press / Random House, 2008.

8 Australasian Society for HIV Medicine. HIV Management in Australasia. A guide for clinical care. Darlinghurst, New South Wales: ASHM, 2009;37-39.

9 Australasian Contact Tracing Manual. 3rd edn. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2006.

10 Littlewood RA, Vanable PA. Complementary and alternative medicine use among HIV-positive people: research synthesis and implications for HIV care. AIDS Care. 2008;20(8):1002-1018.

11 Bormann JE, Uphold CR, Maynard C. Predictors of complementary/alternative medicine use and intensity of use among men with HIV infection from two geographic areas in the United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(6):468-480.

12 Ernst E. The dark side of complementary and alternative medicine. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:797-800.

13 Hennessy M, Kelleher D, Spiers JP, et al. St John’s wort increases expression of P-glycoprotein: implications for drug interactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:75-82.

14 Mills E, Wu P, Ernst E. Complementary therapies for the treatment of HIV: in search of the evidence. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(6):395-403.

15 Liu JP, Manheimer E, Yang M. Herbal medicines for treating HIV infection and AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD003937.

16 Leserman J, Petitto JM, Golden RN, et al. Impact of stressful life events, depression, social support, coping, and cortisol on progression to AIDS. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(8):1221-1228.

17 Leserman J, Jackson ED, Petitto JM, et al. Progression to AIDS: the effects of stress, depressive symptoms, and social support. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(3):397-406.

18 Petitto JM, Leserman J, Perkins DO, et al. High versus low basal cortisol secretion in asymptomatic, medication-free HIV-infected men: differential effects of severe life stress on parameters of immune status. Behav Med. 2000;25(4):143-151.

19 Byrnes DM, Antoni MH, Goodkin K, et al. Stressful events, pessimism, natural killer cell cytotoxicity, and cytotoxic/suppressor T cells in HIV+ black women at risk for cervical cancer. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(6):714-722.

20 Mulder CL, Antoni MH, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Active confrontational coping predicts decreased clinical progression over a one-year period in HIV-infected homosexual men. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(8):957-965.

21 Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Cruess S, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention effects on anxiety, 24-hr urinary norepinephrine output, and T-cytotoxic/suppressor cells over time among symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. J Consult Clin Psychology. 2000;68(1):31-45.

22 Cruess S, Antoni M, Cruess D, et al. Reductions in herpes simplex virus type 2 antibody titers after cognitive behavioral stress management and relationships with neuroendocrine function, relaxation skills, and social support in HIV-positive men. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(6):828-837.

23 Cruess DG, Antoni MH, Kumar M, et al. Reductions in salivary cortisol are associated with mood improvement during relaxation training among HIV-seropositive men. J Behav Med. 2000;23(2):107-122.

24 Creswell JD, Myers HF, Cole SW, et al. Mindfulness meditation training effects on CD4+ T-lymphocytes in HIV-1 infected adults: a small randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(2):184-188.

25 Woods TE, Antoni MH, Ironson GH, et al. Religiosity is associated with affective and immune status in symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(2):165-176.

26 Dalmida SG, Holstad MM, Diiorio C, et al. Spiritual well-being, depressive symptoms, and immune status among women living with HIV/AIDS. Women Health. 2009;49(2/3):119-143.