Chapter 35 HIV Infection and AIDS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) occurs when the virus attaches to and enters helper T CD4 lymphocytes. The virus infects CD4 lymphocytes and other immunologic cells, and the person experiences a gradual destruction of CD4 cells. These cells, which amplify and replicate immunologic responses, are necessary to maintain immune function. When the CD+ lymphocytes are reduced in number, immune functioning begins to fail. As CD4+ lymphocytes decrease, the body is at risk for the development of opportunistic infections (OIs). When these CD4+ lymphocytes have decreased to fewer than 200 cells/mm3 (>15%), the client’s HIV infection has progressed to clinical acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

HIV can also infect macrophages, cells that permit HIV to cross the blood-brain barrier into the brain. B lymphocyte function is also affected, with increased total immunoglobulin production associated with decreased specific antibody production. As the immune system progressively deteriorates, the body becomes increasingly vulnerable to OIs and is also less able to slow the process of HIV replication. HIV infection is manifested as a multisystem disease that may be dormant for years as it produces gradual immunodeficiency. The rate of disease progression and clinical manifestations vary from person to person.

HIV is transmitted only through direct contact with blood or blood products and body fluids, such as cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, human breast milk, semen, saliva, and cervical secretions. In the United States, intravenous drug use, sexual contact, perinatal transmission from mother to infant (also referred to as vertical transmission), and breast-feeding are established modes of transmission. There is no evidence that HIV infection is acquired through casual contact. Administration of zidovudine or nevirapine to pregnant HIV-infected women significantly reduces perinatal transmission.

Currently, the majority of reported cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States occurs in men who have sex with men (MSM). However, the highest rates of new HIV infections are among heterosexual individuals. With advances in the screening of blood products for HIV, the incidence of new infections from blood transfusions has been greatly reduced in developed countries.

Four populations in the pediatric age group have been primarily affected:

1. Infants infected through perinatal transmission from infected mothers; this accounts for more than 90% of AIDS cases among children younger than 13 years of age

2. Children who have received blood products from HIV-infected donors (especially children with hemophilia)

3. Adolescents infected after engaging in high-risk behavior

4. Infants who have been breast-fed by infected mothers (primarily in developing countries)

INCIDENCE

1. Children account for less than 2% of all reported cases of AIDS in the United States.

2. Over 90% of infected children in the United States acquired the infection from their mothers.

3. The number of infants infected by perinatal transmission has decreased significantly as a result of diagnosis and treatment of HIV-infected pregnant women.

4. AIDS is more prevalent in ethnic minority children. Currently, African-American, non-Hispanic children account for 62% of U.S. cases of AIDS, and Hispanic children account for 22%. White children comprise 15% of the total U.S. cases of AIDS.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Infants and Children

The majority of children who are born to HIV-infected mothers become symptomatic during the first 6 months of life, with the development of lymphadenopathy as the initial finding (Box 35-1). The most common clinical manifestations include the following:

5. Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections

7. Chronic or recurrent diarrhea

8. Recurrent bacterial and viral infections

9. Persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection

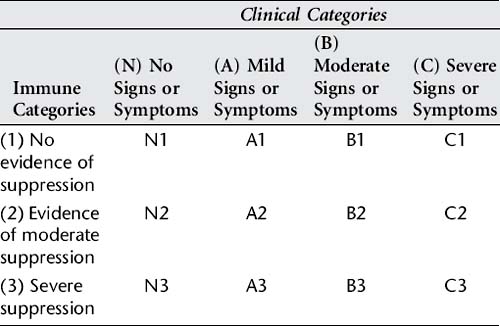

Box 35-1 Clinical Categories of HIV Infection for Children Under 13 Years of Age

Category N: Not Symptomatic or One Condition Listed in Category A

Children with no signs or symptoms thought to be the result of HIV infection

Category B: Moderately Symptomatic

Children who have symptomatic conditions that are attributed to HIV infection:

• Anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia persisting >30 days

• Bacterial meningitis, pneumonia, or sepsis

• Cytomegalovirus infection with onset before 1 month of age

• Diarrhea, recurrent or chronic

• Herpes stomatitis, recurrent

• Herpes simplex virus bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis with onset before 1 month of age

• Herpes zoster (shingles), two or more episodes

• Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP)

• Persistent fever lasting for over 1 month

• Thrush lasting longer than 2 months in a child >6 months

Category C: Severely Symptomatic (AIDS-defining conditions)

Children who have any of the following conditions:

• Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrent

• Candidiasis of the trachea, bronchi, lungs, or esophagus

• Chronic herpes simplex ulcer (>1 month duration) or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis with onset after 1 month of age

• Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

• Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary

• Cryptosporidiosis with diarrhea lasting >1 month

• Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, nodes), onset after age 1 month

• Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision)

• Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

• Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1 month duration)

• HIV malignancies such as lymphoma (Burkitt’s or immunoblastic sarcoma) or lymphoma, primary in brain

• Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, disseminated or extrapulmonary

• Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)

• Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP)

• Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

• Salmonella septicemia, recurrent

Modified from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1994 Revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age, MMWR 43(RR-12):1, 1994.

A significant number of children with HIV infection have neurologic involvement that primarily manifests itself as a progressive encephalopathy, developmental delay, or loss of motor milestones.

Adolescents

Most adolescents who are infected via sexual transmission or through injection drug use may experience an extended period of asymptomatic illness that may last for years. This may be followed by signs and symptoms that begin weeks to months before the development of opportunistic infections and malignancies. The signs and symptoms include the following:

LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

1. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the most commonly used initial test, detects antibody to HIV antigens (almost universally used to screen for HIV antibody in persons older than 2 years of age)

2. Western blot test, the most commonly used test to confirm the ELISA; detects antibody against several specific HIV proteins

3. HIV culture—viral culture requires up to 28 days for positive results; seldom used in the United States

4. HIV DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test—detects HIV DNA; preferred test for children under 18 months of age. Infants born to HIV-infected mothers should have an HIV DNA PCR test at birth or within 48 hours of life, at 1 to 2 months of age, and again at 3 to 6 months of age

5. HIV antigen test—detects HIV antigen; seldom used in the United States

The following laboratory findings may be seen in HIV-infected infants and children:

1. Reduced absolute CD4 lymphocyte count, percentage, and CD4/CD8 ratio

4. Hypergammaglobulinemia (immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin A, immunoglobulin M)

5. Symptomatic children may have a poor response to vaccines

A child born to an HIV-infected mother and who is younger than 18 months of age and who has tested positive on two separate HIV laboratory tests is termed “HIV infected.” A child born to an HIV-infected mother and who is younger than 18 months of age and who has not tested positive to these tests is categorized as “perinatally exposed.”

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

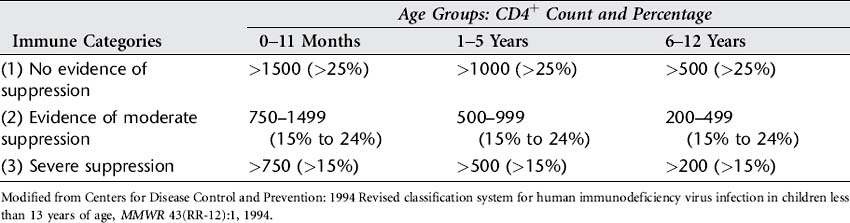

Currently, no cure exists for HIV/AIDS. Antiretroviral medications are used to control viral replication and to prevent disease progression by preservation of the immune system. Management begins with a staging evaluation to determine disease progression and the appropriate course of treatment. Children are categorized according to Table 35-1 using three parameters: immune status, infection status, and clinical status. A child with mild signs and symptoms but with no evidence of immune suppression is categorized as A2. The immune status is based on the CD4 count and CD4 percentage and the child’s age, according to Table 35-2.

Currently four classes of antiretroviral medications are used to control viral replication. These classes are used in a combination therapy termed highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) to treat HIV infection. Table 35-3 provides a summary of the drug classes and their major side effects and/or toxicities. In addition to controlling disease progression, treatment is directed at preventing and managing OIs.

Table 35-3 Antiretroviral Medication Classes and Major Side Effects and Toxicities

| Medication Class | Side Effects and Toxicities |

|---|---|

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor | Anemia, diarrhea, headache, allergic reactions, lactic acidosis, nausea, vomiting, pancreatitis, peripheral neuropathy |

| Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) | Dizziness, vivid dreams, liver function changes, hepatotoxicity, rash |

| Protease inhibitors (PIs) | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, hepatitis, body fat redistribution, nausea, vomiting, kidney stones, rash |

| Fusion inhibitor | Headache, injection site reactions, pain, pneumonia |

Immunizations are recommended for children with HIV infection. Usually, HIV-infected children can receive all immunizations; however, children who are in the immune category III (severe suppression) should not receive the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. In addition, the varicella vaccine is indicated only in HIV-Infected children who are in immune category 1 (no evidence of suppression) with a CD4+ lymphocyte percentage greater than 25.

NURSING INTERVENTIONS

1. Protect infant, child, or adolescent from infectious contacts (Box 35-2); although casual person-to-person contact does not permit HIV transmission, a number of recommendations have been made for children with HIV infection and AIDS.

2. Prevent transmission of HIV infection.

3. Protect child from infectious contacts when he or she is immunocompromised.

4. Assess child’s achievement of developmental milestones and nutritional status.

5. Involve social services, child life therapists, and other health team members to assist child and family with crisis and stresses of chronic illness.

6. Assist family in identifying factors that impede compliance with treatment plan.

7. Encourage child to participate in activities with other children.

Box 35-2 Preventive Measures

Preventive efforts are of vital importance in dealing with HIV/AIDS.

Reducing the number of sexual partners each individual has would decrease the incidence of this disease in the adult and adolescent population, as would involvement in drug rehabilitation programs and avoidance of needle-sharing during drug use.

Elimination of HIV-infected blood and blood products has decreased the likelihood of transmission. Blood and blood products are screened for the HIV antibody, resulting in a blood supply that is much safer.

HIV-infected women in the United States should be instructed not to breast-feed their infants.

Discharge Planning and Home Care

Anabwani GM, Woldetsadik EA, Kline MW. Treatment of HIV in children using antiretroviral drugs. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005;16(2):116.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age. MMWR. 1994;43(RR-12):RR49.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A glance at the HIV/AIDS epidemic (website). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/Facts/At-A-Glance.htm, March 1, 2006. Accessed

Hatherill M. Sepsis predisposition in children with human immunodeficiency virus. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(3):S92.

Hockenberry MJ, et al. Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7. St. Louis: Mosby, 2004.

ed 2. Kirton C, ed. ANAC’s core curriculum for HIV/AIDS nursing. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2003.

McKinney RE, Cunningham CK. Newer treatments for HIV in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16(1):76.

ed 26. Pickering LK, ed. Red book 2003: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics: Elk Grove Village, Ill, 2003.