History taking and examination in obstetrics

Obstetric history

History of present pregnancy

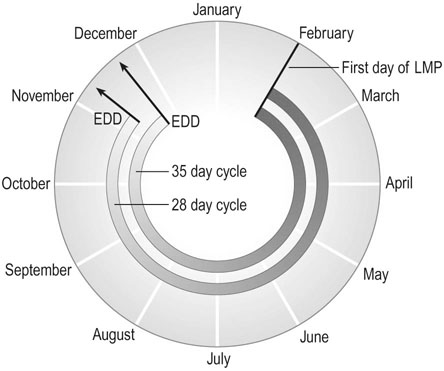

The estimated date of delivery (EDD) can be calculated from the first day of the last menstrual period by adding 9 months and 7 days to this date. However, to apply this Naegele’s rule, the first day of the menstrual period should be accurate and the woman should have had regular 28-day menstrual cycles (Fig. 6.1). The average duration of human gestation is 269 days from the date of conception. Therefore, in a woman with a 28-day cycle, this is 283 days from the first day of the last menstrual period (14 days are added for the period between menstruation and conception). In a 28-day cycle, the estimated date of delivery can be calculated by subtracting 3 months from the first day of the LMP and adding on 7 days (or alternatively, adding 9 months and 7 days). It is important to appreciate that only 40% of women will deliver within 5 days of the EDD and about two-thirds of women deliver within 10 days of EDD. The calculation of EDD based on a woman’s LMP is therefore, at best, a guide to a woman as to the date around which her delivery is likely to occur.

Previous medical history

The natural course of diabetes, renal disease, hypertension, cardiac disease, various endocrine disorders (e.g. thyrotoxicosis and Addison’s disease), infectious diseases (e.g. tuberculosis, HIV, syphilis and hepatitis A or B) may be altered by pregnancy. Conversely, they may adversely affect both maternal and perinatal outcome (see Chapter 9).

Examination

General and systemic examination

Heart and lungs

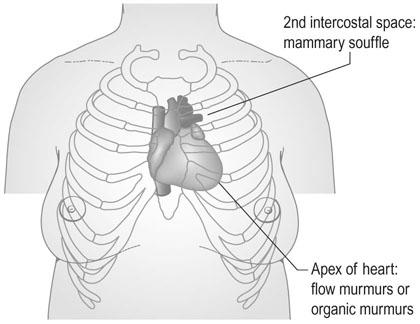

A careful examination of the heart should be made to identify any cardiac murmurs. Benign ‘flow murmurs’ due to the hyperdynamic circulation associated with normal pregnancy are common and are of no significance. These are generally soft systolic bruits heard over the apex of the heart, and occasionally a mammary souffle is heard, arising from the internal mammary vessels and audible in the second intercostal spaces. This will disappear with pressure from the stethoscope (Fig. 6.3).

Breasts

The breasts show characteristic signs during pregnancy, which include enlargement in size with increased vascularity, the development of Montgomery’s tubercles and increased pigmentation of the areolae of the nipples (Fig. 6.5). Although routine breast examination is not indicated, it is important to ask about inversion of nipples as this may give rise to difficulties during suckling, and to look for any pathology such as breast cysts or solid nodules in women who complain of any breast symptoms.

Abdomen

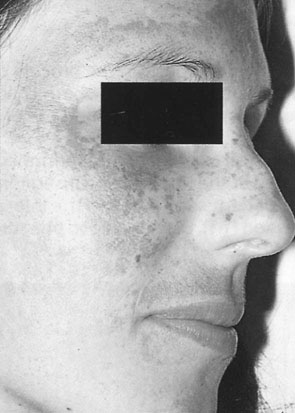

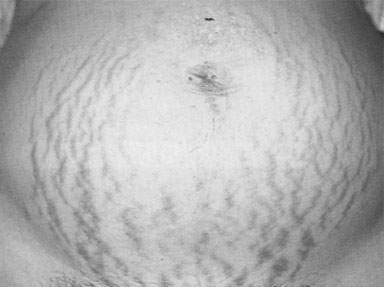

Examination of the abdomen commonly shows the presence of stretch marks or striae gravidarum (Fig. 6.6). The scars are initially purplish in colour and appear in the lines of stress in the skin. These scars may also extend on to the thighs and buttocks and on to the breasts. In subsequent pregnancies, the scars adopt a silvery-white appearance. The linea alba often becomes pigmented and is then known as the linea nigra. This pigmentation often persists after the first pregnancy.

Limbs and skeletal changes

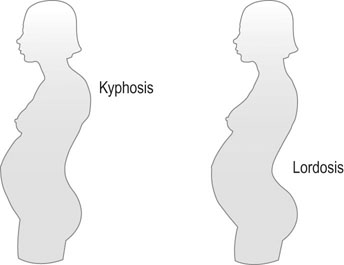

In addition, posture also changes in pregnancy as the fetus grows and the maternal abdomen expands, with a tendency to develop some kyphosis and, in particular, to develop an increased lumbar lordosis as the upper part of the trunk is thrown backwards to compensate for the weight of the developing fetus (Fig. 6.7). This often results in the development of backache and sometimes gives rise to sciatic pain.

Pelvic examination

A speculum examination in early pregnancy is indicated in the assessment of bleeding (see Chapter 18). Pelvic examination in later pregnancy is indicated for cervical assessment (see Chapter 11), the diagnosis of labour and to confirm ruptured membranes (see Chapter 11). Digital vaginal examination is contraindicated in later pregnancy in cases of antepartum haemorrhage until placenta praevia can be excluded.

The role of vaginal examination in normal labour is discussed in Chapter 12.

The technique of pelvic examination in early pregnancy is the same as that for the non-pregnant woman and is described in Chapter 15.

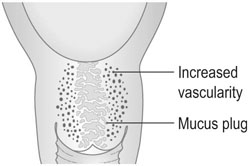

The cervix becomes softened and shows signs of increased vascularity. Enlargement of the cervix is associated with an increase in vascularity as well as oedema of the connective tissues and cellular hyperplasia and hypertrophy. The glandular content of the endocervix increases to occupy half the substance of the cervix and produces a thick plug of viscid cervical mucus that occludes the cervical os (Fig. 6.8).

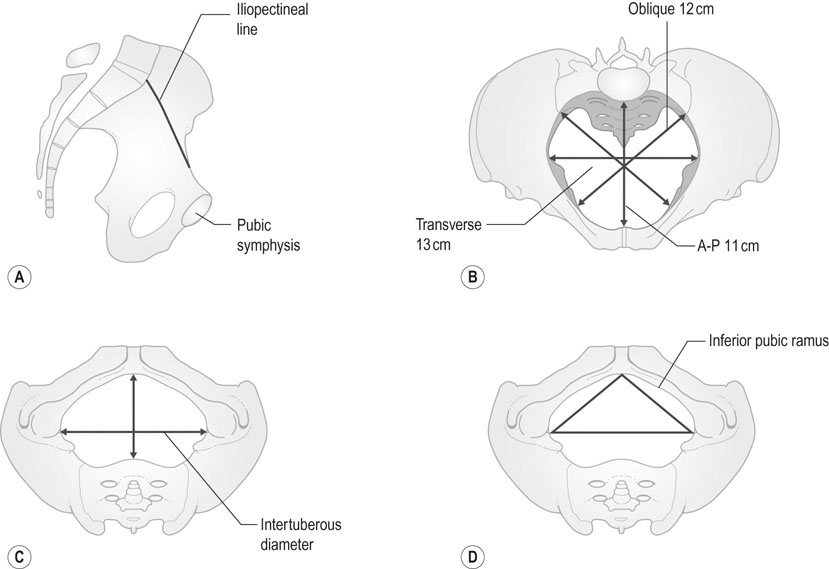

Assessment of the bony pelvis

The bony pelvis consists of the sacrum, the coccyx and two innominate bones. The pelvic area above the iliopectineal line is known as the false pelvis and the area below the pelvic brim is the true pelvis. The latter is the important section in relation to childbearing and parturition. Thus, the wall of the true pelvis is formed by the sacrum posteriorly, the ischial bones and the sacrosciatic notches and ligaments laterally, and anteriorly by the pubic rami, the obturator fossae and membranes, the ascending rami of the ischial bones and the pubic rami (Fig. 6.9).

The planes of the Pelvis

Plane of the pelvic inlet

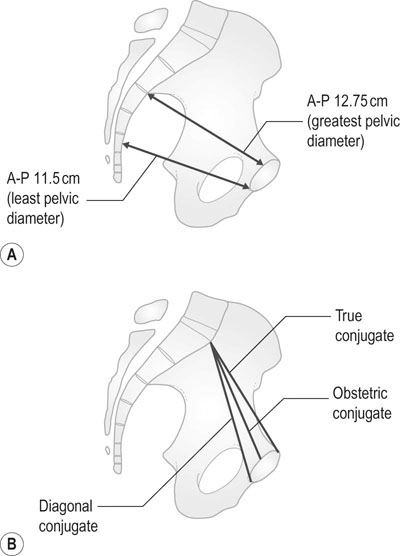

The true conjugate or anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic inlet is the distance between the midpoint of the sacral promontory and the superior border of the pubic symphysis anteriorly (Fig. 6.10). The diameter measures approximately 11 cm. The shortest distance and the one of greatest clinical significance is the obstetric conjugate diameter. This is the distance between the midpoint of the sacral promontory and the nearest point on the posterior surface of the pubic symphysis.

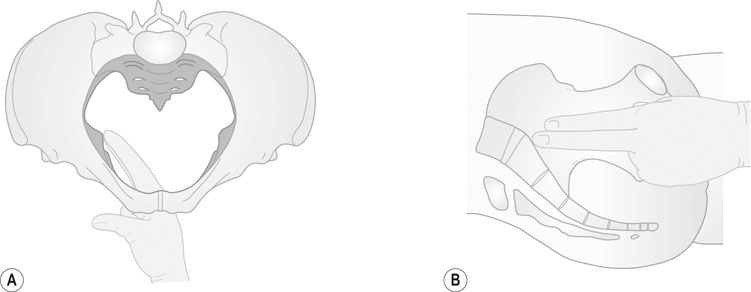

It is not possible to measure either of these diameters by clinical examination; the only diameter at the pelvic inlet that is amenable to clinical assessment is the distance from the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis to the midpoint of the sacral promontory. This is known as the diagonal conjugate diameter and is approximately 1.5 cm greater than the obstetric diameter. In practical terms it is not usually possible to reach the sacral promontory on clinical examination, and the highest point that can be palpated is the second or third piece of the sacrum. If the sacral promontory is easily palpable, the pelvic inlet is contracted (Fig. 6.11A).

Plane of least pelvic dimensions

The plane of least pelvic dimensions represents the level at which impaction of the fetal head is most likely to occur. The anteroposterior diameter extends from the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis and transects the line drawn between the ischial spines. Both the transverse (interspinous) and the anteroposterior diameters can be assessed clinically and the interspinous diameter is the narrowest space in the pelvis (10 cm). The ischial spines should be palpated to see if they are prominent and also to make an estimate of the interspinous diameter (Fig. 6.11B).

Abdominal palpation

Palpation of the uterine fundus

Measurement of symphysial–fundal height

Using two standard deviations from the mean, it is possible to describe the 10th and 90th centile values. The sensitivity of this method for the detection of small for gestational age babies varies from 20% to 70% in different studies. Serial measurements by the same person plotted on customized growth charts are more likely to detect growth restricted babies. The accuracy is considerably reduced as a random observation after 36 weeks gestation. The predictive value is also lower for large-for-dates infants. However, the technique is simple and easily applicable and is particularly useful where other more precise techniques are not available.

Palpation of fetal parts

Fetal parts are not usually palpable before 24 weeks gestation. When palpating the fetus, it must be remembered that the presence of amniotic fluid necessitates the use of ‘dipping’ movements with flexion of the fingers at the metacarpophalangeal joints. The purpose of palpation is to describe the relationship of the fetus to the maternal trunk and pelvis (Fig. 6.13).

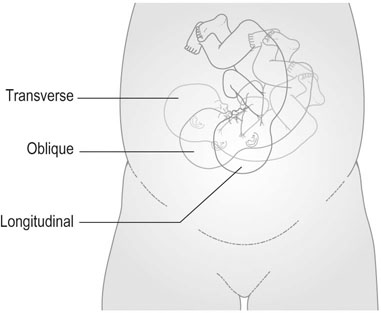

Lie

The term ‘lie’ describes the relationship of the long axis of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus (Fig. 6.14). Facing the feet of the mother, the examiner’s left hand is placed along the left side of the maternal abdomen and the right hand on the right lateral aspect of the uterus. Systematic palpation towards the midline with the left and then the right hand will reveal either the firm resistance of the fetal back or the irregular features of the fetal limbs.

The normal attitude of the fetus is one of flexion (Fig. 6.15) but on occasions, as with the ‘flying fetus’, it may exhibit an attitude of extension.

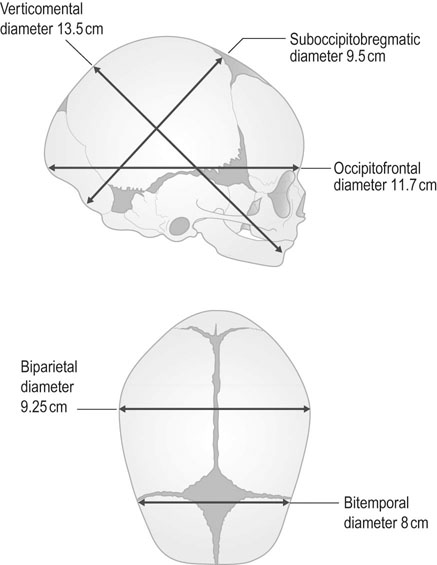

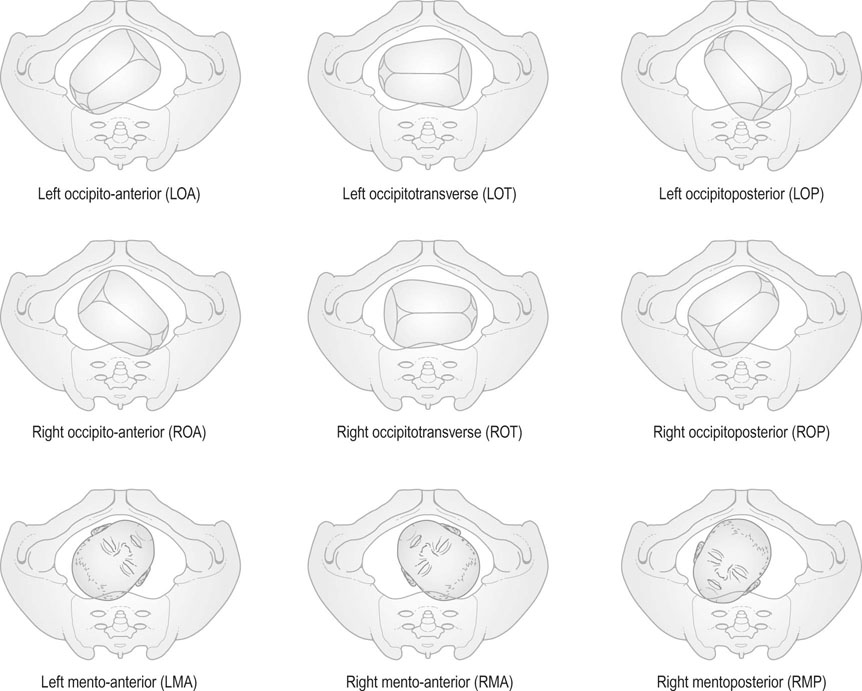

Presentation

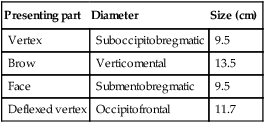

Depending on the degree of flexion or deflexion, various parts of the head will present to the pelvic inlet. Where the head is well flexed, the presentation is the vertex, i.e. the area that lies between the anterior and posterior fontanelles. If the head is completely extended, the face presents to the pelvic inlet (face presentation) and if it lies between these two attitudes, the brow presents (brow presentation). The brow is the area between the base of the nose and the anterior fontanelle. The diameter of presentation for the vertex is the suboccipitobregmatic diameter (Table 6.1, Fig. 6.16). If the head is deflexed, the occipitofrontal diameter presents. With a brow presentation, the verticomental diameter presents to the pelvic inlet. Presentation and position can be accurately determined only by vaginal examination when the cervix has dilated and the suture lines and fontanelles can be palpated. This situation only really pertains when the mother is well established in labour.

Table 6.1

| Presenting part | Diameter | Size (cm) |

| Vertex | Suboccipitobregmatic | 9.5 |

| Brow | Verticomental | 13.5 |

| Face | Submentobregmatic | 9.5 |

| Deflexed vertex | Occipitofrontal | 11.7 |

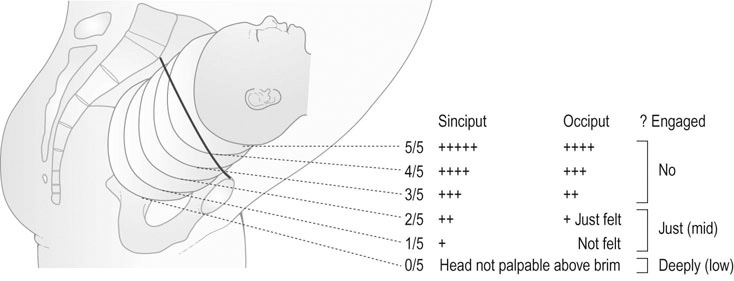

Station and engagement

The station of the head is described in fifths above the pelvic brim (Fig. 6.18). The head is engaged when the greatest transverse diameter (the biparietal diameter) has passed through the inlet of the true pelvis. The head that is engaged is usually fixed and only two-fifths palpable. It is usually difficult to feel abdominally.

Where it is difficult to locate the head, this may either be because the head is under the maternal rib cage, as with a breech presentation, or because it is a case of anencephaly.

Auscultation

Auscultation of the fetal heart rate is a routine part of the obstetric examination. It is now standard practice to use a hand-held Doppler ultrasound device that will produce an electronic signal to enable the heartbeat to be recognized and counted, but should be confirmed with a Pinard fetal stethoscope (Fig. 6.19). The fetal heart sounds are best heard in late pregnancy below the level of the umbilicus over the anterior fetal shoulder (approximately half way between the umbilicus and the anterior superior iliac spine) or in the midline where there is a posterior position. With a breech presentation the sound is best heard at the level of the umbilicus. The rate and rhythm of the heart beat should be recorded.