CHAPTER 8 History, Physical Examination, and the Preoperative Evaluation

Gathering a Patient History

Finally, a review of systems is part of every comprehensive history. This review includes changes in the patient’s respiratory, neurologic, cardiac, endocrine, psychiatric, gastrointestinal, urogenital, cutaneous skin, or musculoskeletal systems. The otolaryngologist often may derive more insight into the patient’s problem by inquiring about constitutional changes such as weight loss or gain, fatigue, heat or cold intolerance, rashes, and the like (Box 8-1).

Physical Examination

Facies

After assessing the patient’s overall appearance, the face should be analyzed for facial asymmetry by positioning the head squarely in front of the examiner. For instance, in patients considering facial plastic surgery, a hemifacial microsomia may affect the final outcome, which should be discussed before the operation. In addition, a paretic facial nerve always is a serious finding that can be detected by observing the tone of the underlying facial musculature and overlying facial skin. Facial wrinkles are more prominent when the facial nerve is functioning. For patients recovering from facial nerve paralysis, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) Facial Nerve Grading System is a respected standard for reporting gradations of nerve function (Table 8-1).

| Grade | Facial Movement | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Normal | Normal facial function at all times |

| II | Mild dysfunction | Forehead: moderate-to-good function |

| Eye: complete closure | ||

| Mouth: slight asymmetry | ||

| III | Moderate dysfunction | Forehead: slight-to-moderate movement |

| Eye: complete closure with effort | ||

| Mouth: slightly weak with maximum effort | ||

| IV | Moderately severe dysfunction | Forehead: none |

| Eye: incomplete closure | ||

| Mouth: asymmetrical with maximum effort | ||

| V | Severe dysfunction | Forehead: none |

| Eye: incomplete closure | ||

| Mouth: slight movement | ||

| VI | Total paralysis | No movement |

Neck

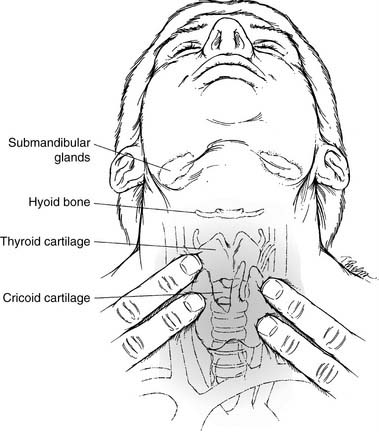

The neck, an integral part of the complete otolaryngology examination, is best approached by palpating it while visualizing the underlying structures (Fig. 8-1). The midline structures such as the trachea and larynx can be easily located and then palpated for deviation or crepitus. If there is a thyroid cartilage fracture, tenderness and crepitus may be present. In thick, short necks, the “signet ring” cricoid cartilage is a good landmark to use for orientation. The hyoid bone can be inspected and palpated by gently rocking it back and forth.

Triangles of the Neck

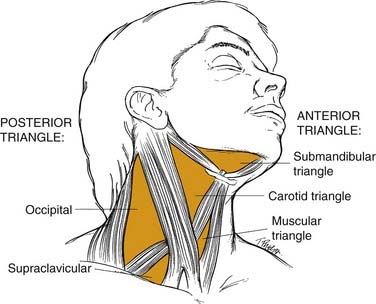

Most physicians find it helpful to define the neck in terms of triangles when communicating the location of physical findings (Fig. 8-2). The sternocleidomastoid muscle divides the neck into a posterior triangle—whose boundaries are the trapezius, clavicle, and sternocleidomastoid muscles—and an anterior triangle—bordered by the sternohyoid, digastric, and sternocleidomastoid muscles. These triangles are further divided into smaller triangles. The posterior triangle houses the supraclavicular and the occipital triangles. The anterior triangle then may be divided into the submandibular, carotid, and muscular triangles.

Lymph Node Regions

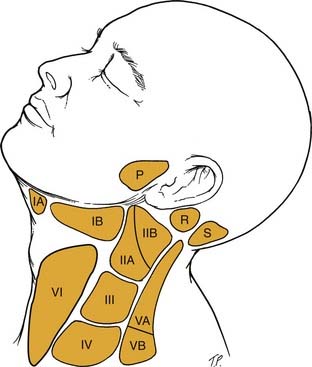

Another classification system for neck masses, endorsed by the American Head and Neck Society and the AAO-HNS, uses radiographic landmarks to define six levels to depict the location of adenopathy (Fig. 8-3). Level I is defined by the body of the mandible, anterior belly of the contralateral digastric muscle, and the stylohyoid muscle. Level IA contains the submental nodes, and level IB consists of the submandibular nodes. They are separated by the anterior belly of the digastric muscle.

Ears

Tympanic Membrane

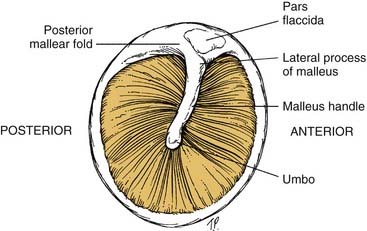

To assess the middle ear for effusions, use the tympanic membrane as a window that allows a view of the middle ear structures (Fig. 8-4). Effusions may be clear (serous), cloudy with infection present, or bloody. When the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver, actual bubbles may form in the effusion.

Hearing Assessment

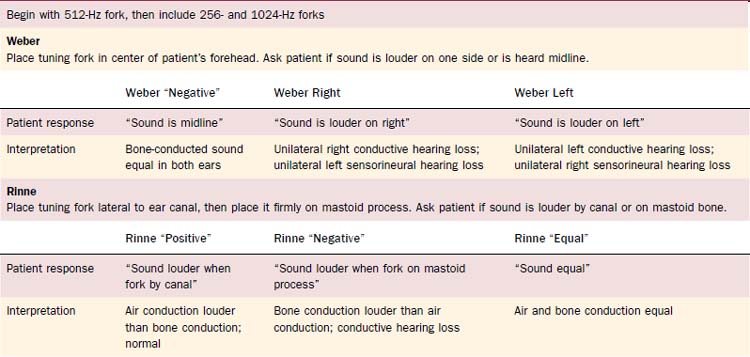

Tuning fork tests, usually done with a 512-Hz fork, allow the otolaryngologist to distinguish between sensorineural and conductive hearing loss (Table 8-2). They also may be used to confirm the audiogram, which may give spurious results because of poor-fitting earphones or variations in equipment or personnel. All tests should be conducted in a quiet room without background noise. Furthermore, one should ensure that the external auditory canal is not blocked with cerumen.

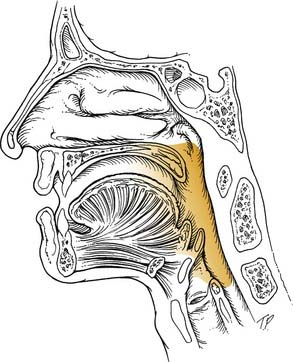

Oropharynx

The oropharynx includes the posterior third of the tongue, anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars, the soft palate, the lateral and posterior pharyngeal wall, the soft palate, and the vallecula (Fig. 8-5). It is best visualized using a head lamp and two tongue depressors. A dental mirror is beneficial in viewing the vallecula and the posterior pharyngeal wall, which often are obscured. Using a gloved finger to examine the base of tongue or tonsil may reveal indurated areas that may be appropriate for biopsy for neoplasm. The patient should be aware of the possibility that gagging may ensue when this is done. In patients with especially strong gag reflexes, a fiberoptic examination may be necessary to fully assess the base of tongue, posterior pharyngeal wall, and vallecula. By carefully passing the flexible fiberoptic endoscope through the anesthetized nose, the interaction of the soft palate and tongue base during swallowing also may be viewed. The uvula should be inspected because a bifid structure may signify a submucosal cleft palate. In addition, an inflamed large uvula may mean the uvula has been traumatized during the night if the patient snores heavily. Small carcinomas or papilloma lesions also may be present, so careful palpation may be indicated.

Larynx and Hypopharynx

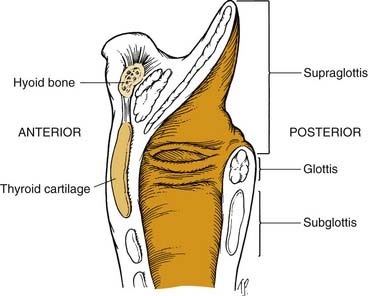

The larynx often is subdivided into the supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis. The supraglottic area includes the epiglottis, the aryepiglottic folds, the false vocal cords, and the ventricles. The glottis comprises the inferior floor of the ventricle, the true vocal folds, and the arytenoids. The subglottis region generally is considered to begin 5 to 10 mm below the free edge of the true vocal fold and to extend to the inferior margin of the cricoid cartilage, although this is somewhat controversial (Fig. 8-6).

Correct positioning of patients increases their comfort while maximizing the examiner’s view of the larynx. The legs should be uncrossed and placed firmly on the footrest. The back should be straight with the hips planted firmly against the chair. Patients, while leaning slightly forward from the waist, should place their chin upward so that the examiner’s light source is sufficiently illuminating the oropharynx. After discussing the examination procedure with the patient, the patient’s tongue is pulled forward by the examiner, who uses a gauze sponge between the thumb and index finger. This allows the physician’s long middle finger to retract the patient’s upper lip superiorly. A warm dental mirror (to prevent fogging) is placed in the oropharynx and elevates the uvula and soft palate to view the larynx (Fig. 8-7). The patient with a strong gag reflex may benefit from a small spray of local anesthetic to help suppress the reflex.

Neurologic Examination

Table 8-3 outlines the basics of a neurologic examination appropriate for most head and neck patients. Certainly patients presenting with vertigo or dysequilibrium require a highly specialized neurologic examination, but that is beyond the scope of this chapter. Much valuable clinical information can be obtained with an evaluation of the cranial nerves.

| Cranial Nerves | Tests |

|---|---|

| I | Sense of smell to several substances |

| Do not use ammonia (common chemical sense caused by CN V stimulation) | |

| II | Visual acuity |

| Visual fields | |

| Inspect optic fundi | |

| III | Extraocular movements in six fields of gaze |

| IV | Pupillary reaction to light |

| V | Palpate temporal and masseter muscles |

| Patient should clench teeth | |

| Test forehead, cheeks, jaw for pain, temperature, and light (cotton) touch | |

| Corneal reflex (blinking in response to cotton touching the cornea) | |

| VI | Near reaction to light |

| Ptosis of upper eyelids | |

| VII | Symmetry of face in repose |

| Raise eyebrows, frown, close eyes tightly, smile, puff out cheeks | |

| VIII | Auditory—tuning fork tests for hearing |

| Vestibular—nystagmus on lateral gaze; Hallpike-Dix test; head shaking; caloric testing; Frenzel lenses | |

| IX, X | Hoarseness |

| True vocal cord mobility | |

| Gag reflex (CN IX or X) | |

| Movement of soft palate and pharynx | |

| XI | Shrug shoulders against examiner’s hand (trapezius muscle) |

| Turn head against examiner’s hand (sternocleidomastoid muscle) | |

| XII | Stick tongue out |

| Tongue deviates toward side of lesion | |

| Tongue atrophy, fasciculations |

CN, cranial nerve.

Preoperative Evaluation

Systems

Adkins RBJr. Preoperative assessment of the elderly patient. In: Cameron JL, editor. Current Surgical Therapy. St Louis: Mosby, 1992.

Buckley FP. Anesthesia and obesity and gastrointestinal disorders. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, editors. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1989.

Curzen N. Patients with permanent pacemakers in situ. In: Goldstone JC, Pollard BJ, editors. Handbook of Clinical Anesthesia. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

Davies W. Coronary artery disease. In: Goldstone JC, Pollard BJ, editors. Handbook of Clinical Anesthesia. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

Ellison N. Hemostasis and hemotherapy. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, editors. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1989.

Gelman S. Anesthesia and the liver. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, editors. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1989.

Goldstone JC. COPD and anesthesia. In: Goldstone JC, Pollard BJ, editors. Handbook of Clinical Anesthesia. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

Graf G, Rosenbaum S. Anesthesia and the endocrine system. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, editors. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1989.

Hirsch NP, Smith M. Central nervous system. In: Goldstone JC, Pollard BJ, editors. Handbook of Clinical Anesthesia. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

Hurford WE. Specific considerations with pulmonary disease. In Firestone LL, Lebowitz PW, Cook CE, editors: Clinical Anesthesia Procedures of the Massachusetts General Hospital, ed 3, Boston/Toronto: Little, Brown, 1988.

Kovatsis PG. Specific considerations with renal disease. In Davidson JK, Eckhardt WFIII, Perese DA, editors: Clinical Anesthesia Procedures of the Massachusetts General Hospital, ed 4, Boston/Toronto/London: Little, Brown, 1993.

Long TJ. General preanesthetic evaluation. In Davidson JK, Eckhardt WFIII, Perese DA, editors: Clinical Anesthesia Procedures of the Massachusetts General Hospital, ed 4, Boston/Toronto/London: Little, Brown, 1993.

Morgan C. Cardiovascular disease, general considerations. In: Goldstone JC, Pollard BJ, editors. Handbook of Clinical Anesthesia. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

Robbins KT, Clayman G, Levine PA, et al. Neck dissection classification update. Revisions proposed by the American Head and Neck Society and the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:751.

Rotter S. Specific considerations with cardiac disease. In Davidson JK, Eckhardt WFIII, Perese DA, editors: Clinical Anesthesia Procedures of the Massachusetts General Hospital, ed 4, Boston/Toronto/London: Little, Brown, 1993.

Strang T, Tupper-Carey D. Allergic reaction. In: Goldstone JC, Pollard BJ, editors. Handbook of Clinical Anesthesia. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996.

Sussman GL, Beezhold DH. Allergy to latex rubber. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:43.

Vandam LD, Desai SP. Evaluation of the patient and preoperative preparation. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, editors. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1989.