2 History of onabotulinumtoxinA therapeutic

Summary and Key Features

• Botulinum toxin has become a valuable therapy for treating selected neurological and urological disorders and managing the appearance of glabellar facial lines

• After identification of a muscle-relaxing substance present in sausages, scientists attributed these effects to a bacterium that became known as Clostridium botulinum. They isolated and characterized the neurotoxin, and described its mechanism of action on nerve terminals

• Dr Alan Scott, an ophthalmologist in San Francisco, began studying botulinum toxin type A (‘Oculinum’) in the 1960s and 1970s as a possible treatment for patients with strabismus

• Following Alan Scott’s successful studies in strabismus patients, he and others, including our group at Columbia University working under a research protocol, examined botulinum toxin type A in several neurological conditions, including blepharospasm, cervical dystonia, and also hyperfunctional facial lines, marked by the overactivity of facial or neck muscles

• Oculinum was approved for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm by the United Stated Food and Drug Administration in 1989

• Alan Scott’s first manufactured research therapeutic, Oculinum, was later acquired by Allergan and renamed Botox®

• Other botulinum toxin products have subsequently been licensed, each having its own clinical profile and dosing strategy; today these products have unique non-proprietary names

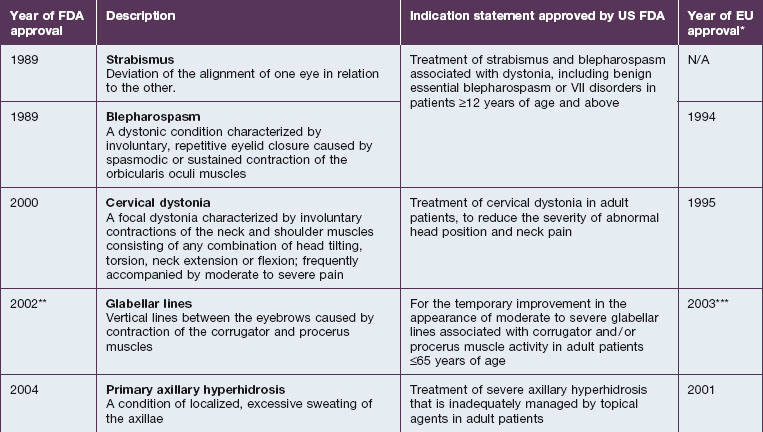

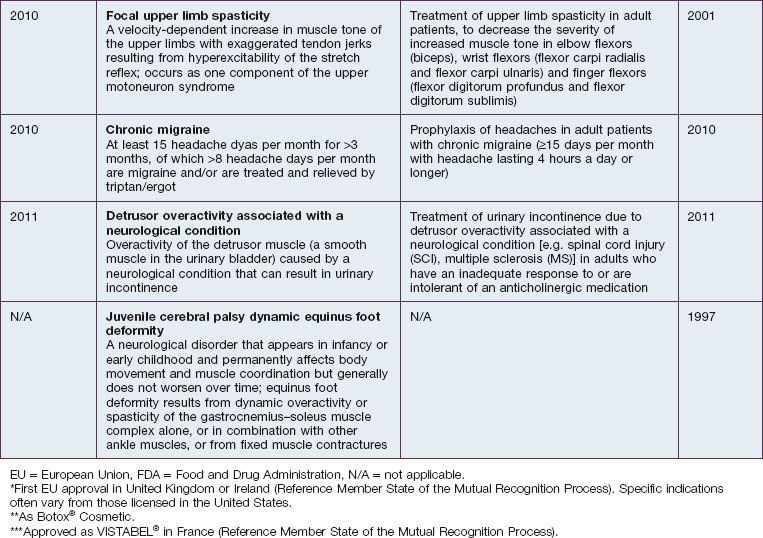

• As of 2011, onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox® / Botox® Cosmetic) is approved for multiple indications worldwide, including eight indications in the United States

• In providing a treatment option for several rare neurological conditions, the clinical development of onabotulinumtoxinA may have contributed to an enhanced understanding of these disorders

Identification, isolation, and characterization

The first well-described cases of medical illness after oral ingestion of an apparent foodstuff that may have contained some botulinum toxin were reported between 1817 and 1822 by the German physician Justinus Kerner. Kerner noted that the active substance interrupted signals from the motor nerves to muscles, but spared sensory nerves and cognitive abilities. He also theorized that the substance could possibly be used as therapy for medical conditions when ingested orally.

The bacterial etiology of botulism was first noted by the microbiologist Emile Pierre van Ermengen who documented his findings in 1897, identifying and naming the responsible bacteria as Bacillus botulinus, which later became Clostridium botulinum. In 1905, Tchitchikine found that C. botulinum produced a substance that affected neurotransmitter function. In 1919, Professor Burke of Stanford University described an alphabetical classification for the different serotypes of botulinum toxin based on his toxin–antitoxin experiments.

Exploration of clinical potential

Scott took the crystalline toxin into his laboratory and diluted it into small aliquots, buffered it with albumin instead of gelatin, and developed testing and storage conditions. He found that injecting minute amounts into extraocular muscles of monkeys with electromyographic (EMG) guidance produced long-lasting effects for the correction of strabismus and, at the doses used, without any systemic effects. Scott published these preclinical results in 1973, performed additional preclinical toxicology studies to evaluate doses that produced systemic effects in primates and obtained an Investigational New Drug (IND) designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to conduct the first clinical trial for humans with strabismus in 1977 by injecting minute amounts locally into the extraocular muscles. He called his formulation ‘Oculinum’ (Fig. 2.1). This clinical trial led to the 1980 publication of the first 19 patients, where efficacy in treating strabismus was reported.

Developed indications for onabotulinumtoxinA

OnabotulinumtoxinA is approved for eight different indications in the United States, which are described in Table 2.1 along with their year of approval and the US FDA indication. Table 2.1 also lists the approval years for these indications in the European Union (EU).

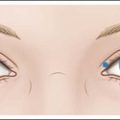

Strabismus

As noted previously, the therapeutic use of botulinum toxin type A began with strabismus, in 1978 when Alan Scott used the toxin to treat the disorder in children after successful experiments in monkeys. The rationale for treating strabismus was that the toxin would create weakness in the injected ocular muscles, causing them to relax over time. This would enable the antagonist muscles contract more effectively, achieving the desired result. Scott noted in 1980 that, along with its efficacy in strabismus correction, botulinum toxin type A was an appropriate therapeutic agent because it had no known effects other than muscle paralysis, had no antigenic effects at small doses and, based on his experience at the time, did not diffuse to muscles adjacent to those injected, produced dose-dependent effects that could last for several weeks, and, in the treatment of strabismus, did not show systemic effects.

Cervical dystonia

Shortly after beginning our research with onabotulinumtoxinA, we were funded by the FDA’s Office of Orphan Product Development to conduct a double-blind study examining the efficacy of onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of cervical dystonia, the results of which were reported by Greene et al in 1990. Later, based on an Allergan-sponsored, pivotal Phase III study, onabotulinumtoxinA was approved by the FDA in 2000 for the treatment of cervical dystonia in adult patients, to reduce the severity of abnormal head position and neck pain.

Primary focal hyperhidrosis

In the 1950s, Ambache reported on animal studies that explored the potential blocking effect of botulinum toxin on sweat glands. Human data were not available until 1994, when Bushara & Park reported areas of anhidrosis around botulinum toxin type A injection sites in hemifacial spasm patients.

Adult post-stroke spasticity

In 1989, Das & Park of the Southend District Stroke Unit of Rochford Hospital in Essex, United Kingdom reported on the use of botulinum toxin type A to treat eight post-stroke patients refractory to conventional therapy and observed improvement in spasticity with an acceptable side effect profile. Many open-label and several double-blind trials followed and have confirmed these findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the editorial assistance of Mary Ann Chapman, PhD.

Ambache N. A further survey of the action of Clostridium Botulinum toxin upon different types of autonomic nerve fibre. Journal of Physiology (Lond). 1951;113:1–17.

Brin MF, Aoki KR, Dressler D. Pharmacology of botulinum toxin therapy. In: Brin MF, Comella C, Jankovic J. Dystonia: etiology, clinical features, and treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004:93–112.

Brin MF, Blitzer A. Botulinum toxin: dangerous terminology errors [letter] [see comments]. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1993;86:493–494.

Brin MF, Fahn S, Moskowitz C, et al. Localized injections of botulinum toxin for the treatment of focal dystonia and hemifacial spasm. Movement Disorders. 1987;2:237–254.

Brooks VB. Vernon Brooks. In: Squire LR, ed. The history of neuroscience in autobiography. New York: Academic Press; 2001:76–117.

Burgen AS, Dickens F, Zatman LJ. The action of botulinum toxin on the neuro-muscular junction. Journal of Physiology (Lond). 1949;109:10–24.

Burke GS. Notes on Bacillus botulinus. Journal of Bacteriology. 1919;4:555–570.

Bushara KO, Park DM. Botulinum toxin and sweating. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1994;57:1437–1438.

Das TK, Park DM. Effect of treatment with botulinum toxin on spasticity. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1989;65:208–210.

Fahn S, List T, Moskowitz CB, et al. Double-blind controlled study of botulinum toxin for blepharospasm. Neurology. 1985;35(Suppl1):271.

Greene P, Kang U, Fahn S, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of botulinum toxin injections for the treatment of spasmodic torticollis. Neurology. 1990;40:1213–1218.

Kerner J. Das Fettgift und die Fettsaure und ihre Wirkungen auf den thierischen Organismus. Ein Beytrag zur Untersuchung des in verdorbenen Wursten giftig wirkenden Stoffes. Stuttgart, Tubingen: Cotta-Verlag; 1822.

Scott A. Development of botulinum toxin (Foreword). In: Jankovic J, Albanese A, Atassi MZ, et al. Botulinum toxin – therapeutic clinical practice and science. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

Scott AB. Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 1980;17:21–25.

Scott AB. Preface. In: Jankovic J, Hallett M. Therapy with botulinum toxin. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1994:vii–ix.

Scott AB. Development of botulinum toxin therapy. Dermatologic Clinics. 2004;22:131–133. v

Simpson LL. The origin, structure, and pharmacological activity of botulinum toxin. Pharmacological Reviews. 1981;33:155–188.

Snipe PT, Sommer H. Studies on botulinus toxin. 3. Acid precipitation of botulinus toxin. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1928;43:152–160.