3 History of cosmetic botulinum toxin

Summary and Key Features

• In the mid-eighties, Dr Jean Carruthers noticed a concomitant improvement in glabellar rhytides in a patient treated with botulinum toxin (BoNT) for blepharospasm

• First trial involved 18 patients and was published in 1992

• By 2002, open-label studies of more than 800 patients confirmed the efficacy and safety of BoNT in the treatment of hyperfunctional wrinkles

• In April 2002, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved BoNT for the non-surgical reduction of glabellar rhytides

• Cosmetic BoNT is now used for hyperkinetic lines in the face, neck, and chest, for facial sculpting, and as an adjunct to other rejuvenating modalities

• The original formulation of BoNT has since gone on to receive approval for 20 indications in more than 75 countries

Introduction

The discovery of ‘sausage poison’ and subsequent identification of Clostridium botulinum as the bacterium responsible has had an enormous and lasting impact on the field of cosmetic dermatology. As is often the case in medicine, a series of serendipitous discoveries – coupled with astute clinical observations – unlocked the potential of botulinum toxin (BoNT) and led to significant medical gains (Tables 3.1 and 3.2). Once hailed as a promising breakthrough for a handful of muscular disorders, BoNT has since become a veritable mainstay of the cosmetic practitioner, its popularity growing exponentially to become one of the most requested procedures in facial rejuvenation.

| Late 1700s | Outbreaks of deadly illness from contaminated foods sweeps across Europe |

| 1793 | Biggest outbreak in Wildebrad, Southern Germany |

| 1811 | ‘Prussic acid’ named as culprit in sausage poisoning |

| 1822 | Dr Justinus Kerner publishes monograph of ‘sausage poison’ and accurately describes botulism |

| 1895 | Professor Emile Pierre Van Ermengem identifies Clostridium botulinum as causative agent of botulism |

| 1895–1915 | Seven serotypes of toxins are recognized |

| 1928 | Dr Herman Sommer isolates most potent serotype: BoNT-A |

| 1946 | Carl Lamanna and James Duff develop concentration and crystallization techniques subsequently used by Dr Edward J. Schantz at Fort Detrick, Maryland, for possible biological weapon |

| 1972 | Dr Schantz takes his research to the University of Wisconsin, where he produces the large batch of BoNT-A that remained in clinical use until December 1997 |

Table 3.2 Timeline of therapeutic development and use

| Late 1960s–early 1970s | Dr Alan Scott begins animal experimentation with BoNT-A supplied by Dr Schantz |

| 1973 | Dr Scott publishes the first report of BoNT-A in primates |

| 1978 | FDA grants approval to begin testing small amounts of the toxin (Oculinum) in human volunteers |

| 1980 | Landmark paper demonstrating that BoNT-A corrects gaze misalignment in humans |

| 1988 | Allergan Inc. acquires rights to distribute Dr Scott’s Oculinum in the United States |

| 1989– | FDA approves BoNT-A for the non-surgical correction of strabismus, blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, and Meige syndrome in adults Clinical use expands to include treatment of cervical dystonia and spasmodic torticollis Allergan purchases Dr Scott’s company and renames the toxin Botox® |

Serendipitous discovery

By the late 1980s, nearly 10 000 patients had received injections of BoNT type A (BoNT-A; then called ‘Oculinum’ and distributed to qualified injectors by Dr Alan Scott of the Smith Kettlewell Institute of Visual Sciences, San Francisco, CA) for the treatment of strabismus, benign essential blepharospasm, and hemifacial spasm (Smith Kettlewell 1990.) Many of these patients had received multiple injections with no evidence of antibody formation or systemic complications over 6 years of continued use. In Vancouver, British Columbia, ophthalmologist Dr Jean Carruthers noticed a remarkable and unexpected effect in the brow of a patient treated for blepharospasm: a noticeable reduction in the appearance of glabellar furrows, giving her a more serene, untroubled expression. Dr Carruthers discussed the observation with her dermatologist spouse, Dr Alastair Carruthers, who was attempting to soften the forehead wrinkles of his patients using soft-tissue-augmenting agents available in the eighties.

Patient zero and the first clinical trials

Intrigued by the possibilities, the Carruthers injected a small amount of Scott’s BoNT-A between the brows of their assistant, Cathy Bickerton Swann – known as ‘patient zero’ – and awaited the results (Figure 3.1A–D). Seventeen more patients followed, aged 34 to 51, who would become part of the first report on the efficacy of BoNT-A, published in 1992. Subjects received injections directly into the glabellar furrow (10–12.5 U/furrow), as well as one or more subsequent injections into the corrugator muscles (10–20 U/furrow or per corrugator) 3 to 4 months following previous injections. One patient did not respond at all to injection, and one was lost to follow-up. The remaining patients experienced varying degrees of brow improvement, from complete line effacement (six of seventeen) (Fig. 3.2) to discernible brow creases that simply lessened in depth (eight subjects). The effects of the toxin lasted from 4 to 11 months, depending on the number of repeated injections and length of exposure. In general, subjects who received treatment over a longer period of time experienced a treatment persistence of 7–11 months. Side effects included one case each of brow and lid ptosis that resolved within 14 days, two cases of transient headache, and one subject who experienced transient numbness at the injection site. Although the authors conclude by saying that BoNT-A is safe and effective, ‘We do not believe at present that it is the treatment of choice’ except for ‘those who are collagen-allergic or who are disinclined to undergo surgery.’

FDA approval

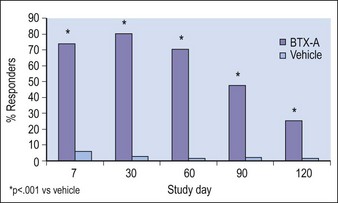

The second large trial was identical in design to the first and comprised 273 patients injected with BoNT-A (n = 202) or placebo (n = 71). As in the first trial, response to BoNT-A peaked at day 30 for both physician- and patient-assessment and was significantly greater than for placebo at every follow-up visit (p <0.001) (Fig. 3.3). No treatment-related serious complications were reported; the most common adverse events in the BoNT-A group were headache (11.4%) and unilateral blepharoptosis (1%).

Blitzer A, Brin MF, Keen MS, et al. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of hyperfunctional lines of the face. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 1993;119:1018–1022.

Blitzer A, Bonder WJ, Aviv JE, et al. The management of hyperfunctional facial lines with botulinum toxin. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 1997;123:389–392.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Botulinum toxin type A: history and current cosmetic use in the upper face. Seminars in Cutaneous and Medical Surgery. 2001;20:71–84.

Carruthers A, Carruthers JDA. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of glabellar frown lines and other facial wrinkles. In: Jankovic J, Hallett M. Therapy with botulinum toxin. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1994:577–595.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Botulinum toxin A in the mid and lower face and neck. Dermatologic Clinics. 2004;222:151–158.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. The evolution of botulinum neurotoxin type A for cosmetic applications. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2007;9:186–192.

Carruthers JA, Lower NJ, Menter MA, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar lines. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002;46:840–849.

Carruthers JD, Lowe NJ, Menter AM, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type A for patients with glabellar lines. for the Botox Glabellar Lines II Study Group. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2003;112:1089–1098.

Carruthers JDA, Carruthers JA. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1992;18:17–21.

Clark RP, Berris CE. Botulinum toxin: A treatment for facial asymmetry caused by facial nerve paralysis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1989;84:353–355.

Fagien S, Carruthers JD. A comprehensive review of patient-reported satisfaction with botulinum toxin type a for aesthetic procedures. Plastics and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;122:1915–1925.

Kane MA. Nonsurgical treatment of platysmal bands with injection of botulinum toxin A. Plastics and Reconstructive Surgery. 1999;103:656–663.

Keen M, Blitzer A, Aviv J, et al. Botulinum toxin A for hyperkinetic facial lines: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Plastics and Reconstructive Surgery. 1994;94:94–99.

Klein AW. Treatment of wrinkles with Botox. Current Problems in Dermatology. 2002;30:188–217.

Kuczynski A, PULSE; Drought Over, Botox Is Back Retrieved April 13, 2011 from http://www.nytimes.com/1997/12/14/style/pulse-drought-over-botox-is-back.html

Liew S, Dart A. Nonsurgical reshaping of the lower face. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2008;28:251–257.

Lowe NJ, Maxwell A, Harper H. Botulinum A exotoxin for glabellar folds: a double-blind, vehicle-controlled study with an electromyographic injection technique. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996;35:569–572.

Lowe NJ, Yamauchi P. Cosmetic uses of botulinum toxins for lower aspects of the face and neck. Clinics in Dermatology. 2004;22:18–22.

Pribitkin EA, Greco TM, Goode RL, Keane WM. Patient selection in the treatment of glabellar wrinkles with botulinum toxin type A injection. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 1997;123:321–326.

Smith Kettlewell Institute of Visual Sciences. Botulinum toxin (Oculinum) study: IND-723. Patients treated as of 31 December 1989. San Francisco, CA.: Smith Kettlewell Institute of Visual Sciences; 1990.

The American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. The American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Releases New Procedure Survey Data. Online. Available http://www.asds.net/TheAmericanSocietyforDermatologicSurgeryReleasesNewProcedureSurveyData.aspx, 2008. 22 July 2010

The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2009 2008 Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics