Chapter 1 History, development and current activity in coronary intervention

Following the first percutaneous coronary angioplasty in 1977, growth in the procedure has been exponential.

Following the first percutaneous coronary angioplasty in 1977, growth in the procedure has been exponential. It is estimated that in 2000, approximately one million angioplasty procedures were undertaken worldwide.

It is estimated that in 2000, approximately one million angioplasty procedures were undertaken worldwide. In the USA the number of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasties (PTCAs) performed annually exceeds that of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) procedures.

In the USA the number of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasties (PTCAs) performed annually exceeds that of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) procedures.HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Cardiac catheterisation and coronary angiography

More than two decades have passed since Andreas Grüntzig (Fig. 1.1) first attempted the percutaneous relief of a coronary stenosis. This single event, representing the culmination of many years of experimentation, has now passed into legend. Percutaneous coronary revascularisation has emerged as a routine cardiac procedure, but the trials and tribulations of workers in the field of invasive cardiology, whose efforts led stepwise to that day in September 1977, are nevertheless worthy of review.

Other developments also allowed cardiac catheterisation to progress to a stage recognisable in the present day. In 1953, Seldinger introduced his technique of entering arteries percutaneously. Serious peri-procedural cardiac arrhythmias could be addressed with closed chest cardiac compression (1960) and the introduction of direct current (DC) defibrillation by Lown in 1962. X-ray documentation had been limited to single plate exposures until the image intensifier coupled to film exposure at rapid frame rates resulted in the emergence of true cineangiography. Cardiac events could thereby be visualised in ‘real time’ incorporating less contrast volume and less radiation exposure to both patient and operator.

Coronary angioplasty

Initial non-surgical attempts to address arterial obstruction focused on the peripheral circulation. Charles Dotter, together with Judkins in 1964, first reported a successful approach in leg arteries using co-axial sheaths to allow sequential dilatations. In an initial series of nine patients with severe perpheral ischaemia; six improved and four amputations were avoided. However, it was recognised that a better mechanical method of dilatation was required which exerted radial, rather than longitudinal force, on the vessel wall. A latex balloon was initially tried, but it was then appreciated that a non-elastic dilator was preferable. In 1974 Andreas Grüntzig developed a sausage-shaped polyvinyl chloride (PVC) balloon, mounted at the end of a catheter, which could be inflated to a predetermined diameter to exert a radial force of 3 to 5 atmospheres. This was initially used in the iliac and femoropopliteal system with satisfactory results, and was then extended to address disease in renal, basilar, coeliac and subclavian arteries.

A report of the first 50 cases was published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 1979, indicating success in 32 patients. Stenosis severity fell from 84% to 34%, with a reduction in the translesional pressure gradient from 58 to 19 mmHg. Seven patients required emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG); there was a 5% incidence of myocardial infarction, but no procedural deaths. In a book prepared before his untimely death in 1985, Grüntzig wrote:

TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

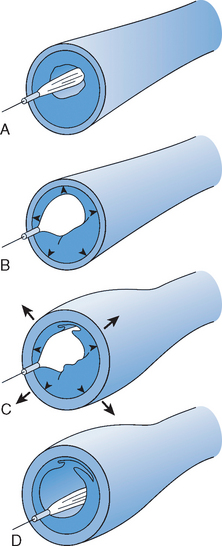

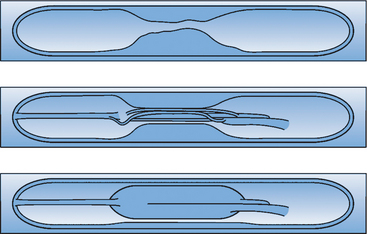

The procedure of coronary angioplasty, although modified over the last 20 years by enhanced technology, still conforms to the original descriptions of the technique (Figs. 1.2 and 1.3). Under radiographic control and local anaesthesia, the coronary arterial ostium is engaged with a guiding catheter and the target lesion traversed with an atraumatic guidewire. A balloon-tipped catheter is then advanced over the guidewire until it reaches the site of atheromatous obstruction, at which point the balloon is inflated with diluted contrast medium. The size of balloon, inflation pressure and the number and duration of inflations, varies according to the lesion characteristics. When the angiographic appearances suggest adequate lesion dilatation, all the equipment is removed and the patient is returned to the ward.

Guiding catheters

Although coronary angioplasty represented an extension of diagnostic angiography, the construction of guiding catheters needed modification as these would need to support the passage of high profile and inflexible balloon catheters through tortuous vessels and across high-grade obstructions, rather than simply allow contrast injection. Initial examples had large outer diameters with poor memory and torque control. In the early 1980s, bonded, multilayer guiding catheters were developed comprising an inner surface of Teflon (to decrease friction), a middle layer of woven mesh (for torque control) and an outer layer of polyurethane (to maintain form). The variety of preformed shapes available for diagnostic work (Judkins, Amplatz), were reflected in the design of guides for interventional use, with many additional configurations to deal with atypical anatomy (e.g. Voda, Multipurpose, El Gamal, Hockey Stick).

Guidewires

A short wire was fixed to the distal tip of the balloon catheter in 1979, but a major advance was made in 1982 when Simpson developed a long moveable and independent guidewire that was inserted through the central lumen. This allowed better tip control and steerability enabling access to distal coronary lesions. The initial 0.018 wires were later to be reduced in diameter and incorporate a variety of lubricious coatings to reduce friction and enhance passage through severe stenoses. Another modification was the introduction of a low profile balloon able to be moved only over a limited segment of reduced diameter wire (Hartzler ‘Micro’).

Balloon catheters

Balloon preparation was often problematical as the material did not collapse easily with aspiration and thus de-airing was frequently incomplete. Until the development of superior materials, this was overcome with a specific air venting tube which was integral in the Simpson–Roberts balloon catheter system.

These, and other technological advances steadily increased the scope of PTCA allowing a larger variety of lesions to be treated more successfully and with greater safety. Angioplasty had grown from a pioneering and unpredictable experiment to become a routine therapy for patients with coronary disease. A further breakthrough was to occur in 1987 which, in significance, was second only to Grüntzig’s pioneering efforts; this was the first implantation in man of an intracoronary stent (see Chapter 6).

WORLDWIDE ACTIVITY

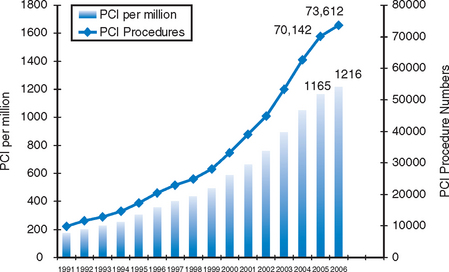

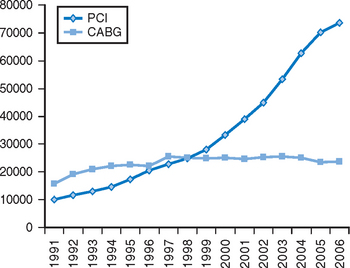

The growth in activity has been seen worldwide, with the USA particularly generating large volumes. It is interesting to note that ten years after the first report of coronary artery bypass grafting in 1968, 100,000 operations had been performed in the USA. However this figure had been overtaken by the number of PTCA procedures (106000) undertaken within only seven years of its first reported series in 1978. Recent UK data suggest that CABG rates may now be on the decline as PTCA activity continues to increase (Fig. 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Comparison of rates of PCI and CABG in the UK.

Source: BCIS Audit Returns (2006) (www.bcis.org.uk)

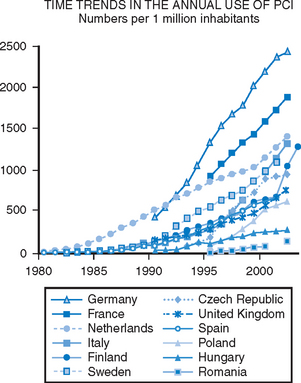

In 1995, there were an estimated 350 000 PTCA cases performed in the USA, with almost 500 000 undertaken worldwide. In Europe, activity has been similarly increasing from approximately 250 000 in 1995, to almost 300 000 in 1997. Individual European countries differ in interventional activity and thus in the PTCA rates per million of the population (Fig. 1.5). Growth in activity in the UK, although substantial, nevertheless lags behind that of other European countries like France, Germany and Belgium. This discrepancy in the UK compared with other Western European nations is primarily a funding issue within the National Health Service (NHS). A lack of resources limits the number of patients coming forward for angiographic investigation, and thereby the number available for revascularisation with CABG as well as PTCA.

Figure 1.5 Comparison of time trends in European PCI activity.

Source: Euroheart Survey, 3rd Report (www.escardio.org)

In the UK, data on PTCA activity is collected by the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) on an annual basis. Input from participating centres has been voluntary, but nevertheless the volumes recorded have always been in concordance with those suggested by industry sources when equipment sales have been examined. Thus in 1991, 52 centres in the UK undertook 9933 PTCA procedures representing 174 cases per million population. The annual growth in activity has varied between approximately 12% and 19%, the average since 1991 being 15% per year. In 2006, a total of 91 centres reported almost 74 000 procedures, giving a rate per million of 1216 (Fig. 1.6).