CHAPTER 110 History and Principles of Pain Rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

Pain rehabilitation is a specific form of rehabilitation medicine applied to the management of chronic pain. To qualify, it is important to distinguish between acute and chronic pain. Acute pain is a self-limiting form of noxious stimulation following tissue injury that persists during that period of time during which the body would be expected to repair itself and recover to its preexistent biological status. Chronic pain is a condition which lasts beyond the reparative phase. Secondary physical and behavioral effects develop that create disability and an inability to function. A variety of adverse events tend to be associated with the development of chronic pain including drug abuse, further decreased function, psychiatric abnormalities, multiple unsuccessful surgical interventions, social and economic isolation, and even suicide.1

Unfortunately, surgical disciplines confounded this approach by developing more complicated operative remedies for which success was claimed, but whose supportive data base was questionable. The burgeoning world of anesthesiologic interventional techniques also claimed success, again unsupported by scientifically reliable data. The rehabilitation model appears to have produced the most acceptable data and, at least, has equal or better outcome results without the risks attending all interventional applications.2

THE NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL BASIS OF PAIN REHABILITATION

Pain rehabilitation enables patients with chronic pain to return to a productive lifestyle. Pain centers or clinics are facilities where patients are sent for the treatment of chronic pain, after conventional management has failed and no further directed disease-oriented care is deemed appropriate.3

Patients who are considered candidates for pain rehabilitation have chronic pain, illness, disability conviction, and are physically and functionally impaired. Pathological abnormalities must be distinguished from dysfunction. Activation must occur before pain is resolved.4,5

Patients with chronic pain present a clinical challenge because of the vast time and the diagnostic and therapeutic resources they consume. The pain management approach must be capable of properly identifying patients’ problems whether sensory, perceptual, psychological, psychosocial, environmental, or biomechanical in nature. Treatment goals are to reduce chronicity, prevent re-injury or disability, and restore function, as well as to return the patient to a productive lifestyle.6

The original concept that nerve root compression from a herniated disc produces pain was challenged decades ago when Rosomoff7 presented a series of observations together with clinical and experimental evidence that supported the contention that alternative nonsurgical methods will provide successful treatment even for manifest disc herniations or lumbar stenosis. Physiologic studies demonstrated that, except for a transient painful impulse when the nerve is first impacted, sustained nerve root compression or ‘pinching’ does not produce pain.8 There could be numbness or loss of function, but this is not a painful event.

From inspection of human anatomy, it is inescapably clear that all low back injuries must have associated soft tissue abnormalities. Even if the forces causing the injury reach sufficient magnitude to herniate or rupture an intervertebral disc, the force must be transmitted first through the surrounding soft tissue that binds the spine together as a functional unit. These tissues, when injured, undergo a breakdown of the cell membranes to arachidonic acid, from which biosynthesis of prostaglandins and associated products ensues. One important issue in this process is the induction of a state of hyperalgesia, following which a pain signal will evolve when excessive mechanical stimulation occurs or when compounds of reaction to injury, such as histamine or bradykinin, are produced.9 The nerve itself does not originate the pain signal; nociceptors are stimulated to initiate the transmission of the signal.

It is our thesis that the disordered musculoskeletal system is responsible for initiating these phenomena.3,7,10 These structures are in the surrounding paraspinal muscles, buttocks, hips, and legs. These peripheral sites are treatable by alternative medical approaches. Treatment will restore function and alleviate pain, often without the need for correcting intraspinal abnormalities that have traditionally been designated as the pain generator. Further, a study carried out in 45 000 patients with low back pain indicated that only 1 in 200 of patients may actually need surgical intervention;11 in our experience the number of patients is 1 in 500.

Muscular and fascial abnormalities are called myofascial syndromes. They have been well described by Travell and Simons.12 Abnormal movements of the back, restricted ranges of motion in the hips or legs, or the presence of muscle tenderness and/or trigger points, are seen with myofascial syndromes. These can perpetuate mechanical dysfunction, continued strain, muscle fatigue, and pain.

ALGORITHM FOR PAIN REHABILITATION

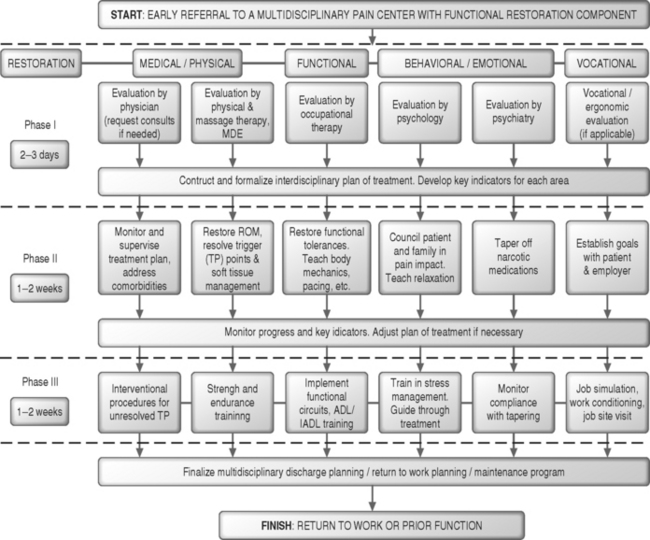

Although it can be described in discrete phases, rehabilitation is a continuous process of evaluation, treatment, conditioning, and reevaluations. The intensity and duration of each process depends on a variety of parameters including patient’s response, rate of progress, the presence of comorbidities, and the number and type of objectives to be met. The algorithm is depicted in Figure 110.1 and the elements are described below.

Admission criteria

To enter the system, the patient undergoes evaluation over a 3-day period. The rehabilitation team attempts to identify the medical, behavioral, vocational, financial, social, and other significant problems. The approach is comprehensive and holistic. Patient selection criteria are broad. The patient must have the ability to understand and carry out instructions, must be compliant and cooperative, and must not have aggressive or disruptive behavior that would disturb the milieu. Patients with schizophrenia, manic-depression, or other major psychiatric disorders are not precluded as long as they are receiving treatment which renders them stable. The patient, the family, and significant others, such as the lawyer, the employer, and the insurer must be accepting of vthe program. Worker compensation, liability cases, multiple surgeries, long histories of invalidism, or drug abuse are not exclusionary conditions. Although integral, the financial, legal, and administrative aspects of patient admission are beyond the scope of this chapter.

Activation and physical restoration

A daily treatment schedule is designed to accommodate the various treatments and disciplines. A typical treatment schedule for one patient is shown in Table 110.1. The contents of each patient’s schedule vary on a daily basis depending on the stage (week) in treatment, level of activation, and progress.

| Patient name___________________ | |

|---|---|

| Time | Activity |

| 8:00–8:30 | Movement therapy, warm up, low-impact aerobics |

| 8:30–10:00 | Physical therapy, stretching, modalities, back exercises, functional electrical stimulation, active exercises, gait training, flare-up procedures |

| 10:00–11:30 | Occupational therapy, body mechanics training, biofeedback, functional circuits, pacing, walking, climbing, lifting, carrying, pushing/pulling, reaching, safety, joint protection, ADL training |

| 11:30–12:00 | Psychological counseling, family counseling, stress management, breathing exercises, hypnosis, vocational counseling, vocational preparation, case management |

| 12:00–1:00 | Lunch break |

| 1:00–1:30 | Strength and cardiovascular training |

| 1:30–2:00 | Neuromuscular massage therapy |

| 2:00–3:00 | Occupational therapy, upper extremity activities exercises, educational activities, work simulation |

| 3:00–4:00 | Group activity, educational sessions |

| 4:00 | Evening activities, recreational activities |

A very effective tool in this phase is the concept of daily goals, final goal setting, and self-monitoring. Computerized modeling is used to determine optimal pathways a patient should follow during rehabilitation. The model utilizes statistical projection methods, which take into consideration the patient’s initial performance level and the desired goals.13 This nonlinear model derives its coefficients from retrospective data collected from over 1000 patients with chronic pain who successfully completed the 4-week rehabilitation and functional restoration program, and who have returned to a productive lifestyle. Once initial levels of performance have been measured and treatment goals have been determined, the daily goals are assigned to provide a personalized print-out of the expected ‘daily’ performance. The daily goals program provides daily increments for the patient’s therapeutic activities. The optimal progression print-out from initial tolerances to final goals is used by the patient and the treating staff to determine effects needed to achieve the desired daily performance throughout treatment.

EVALUATION OF FUNCTIONAL DISABILITY

Physician evaluation

The entry to evaluation and treatment is through the physician. The physician must obtain a detailed, accurate history. The mechanism of injury and the precise location of the pain at onset are critical. A neurologic examination evaluates reflexes, muscle strength, and sensory status to document the presence or absence of neurologic deficits.14 Although neurologic screening is essential, it is most often not significantly positive. In fact, only 1% of individuals have neurologic dysfunction which is reversible usually and, therefore, should not be considered as a pathological deficit. The soft tissue examination must be sophisticated and thorough.15 All musculoskeletal and myofascial abnormalities must be identified. This is particularly important, since myofascial syndromes may simulate neurological syndromes, particularly radiculopathies. The straight leg raising (SLR) test may produce leg pain considered to be indicative of irritated nerve roots, but this occurs even more regularly with myofascial syndromes. Contractures of the hip musculature, particularly the hip rotators, are common and disabling with standing or walking, so that restricted ranges of motion about the hips are not necessarily an indicator of articular disease. Palpable soft tissue tenderness by itself, again, is thought by some to be less specific or reliable, but, to reiterate, tender/trigger points and restricted ranges of motion are the hallmark of myofascial syndromes and must be sought so they can be identified and treated. They are, in fact, objective findings.

Simple laboratory tests, including blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, are sufficiently inexpensive and efficacious for use as initial tests when there is suspicion of back-related pathology, such as tumor or infection. Lastly, special tests such as radiographs, imaging techniques, electrodiagnostics, thermography, and discography should be reviewed or recommended, if deemed necessary, but should be interpreted with extreme caution.10

Motor dysfunction evaluation

This is a method developed to identify and effectively treat ‘motor’ dysfunction in patients with chronic pain conditions.16 This innovative testing utilizes on-line computerized electromyographic (EMG) methods to study recruitment of muscles involved in a chain of motor activities.17 This method may detect functional muscular abnormalities that cannot be identified by clinical examination, even by experienced observers. The EMG signals of the various muscles are examined for baseline activity, symmetry, magnitude, frequency contents, synchrony, timing, and patterns. Patients’ behaviors are also observed. Motor dysfunction evaluation (MDE) findings are then compared to relevant clinical findings. Patient-specific, as well as condition-specific, multidisciplinary approaches are then generated to deal with the problems during daily treatment. The overall objective is to improve function and accelerate restoration. This is accomplished through using EMG and other electrically assisted methods to increase sensory perception of muscles and joints; increase neuromuscular recruitment; increase strength and endurance; and reestablish synchrony, symmetry, pattern, and synergy of muscle activity, thereby increasing functional capacities and reduction of pain.

Behavioral therapy/psychological evaluation

This examination reveals a great deal about the patient’s mental state, behaviors, coping styles, and the effects of pain or injury on personality. Behavioral analysis considers compliance, achievement level before injury, activity level after injury, functional capacities, anxiety, depression, personality disorders, marital status, role reversal, and family dysfunctional states. There are psychological tests designed to elicit responses which can be translated into numerical values and compared with the performance of other persons, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory and the Millon Behavioral Health Inventory Assessment. These instruments test psychogenic attitudes, such as chronic tension, recent stress, premorbid pessimism, future despair, social alienation, and somatic anxiety. They are not a predictor of outcome, nor should they be used for that purpose. We no longer use these instruments, but depend heavily on individual interview assessments.18 If utilized, it should be for the purpose of finding out how the treating staff can interact with the individual in an effective manner to allow the patient to accept the rehabilitation plan. The patient has to be a partner in the rehabilitative process; otherwise, the effort will fail.

Vocational evaluation

The objectives of vocational evaluations are:

COMPONENTS OF PAIN REHABILITATION (INTERVENTIONS)

Medication/narcotics

The coanalgesic group of drugs may be used to enhance the effect of opioids or NSAIDs, have independent analgesic activity in certain situations, or counteract the side effects of analgesics. Neuropathic pain represents 30–40% of this treatment group. This is pain which has a burning, prickling quality which has been called dysesthetic pain as compared to the sharp, toothache-like pain managed with standard analgesics. Included in this group would be the tricyclic antidepressants, the antiepileptic drugs, local anesthetics, glucocorticoids, skeletal muscle relaxants, antispasmodial agents, antihistamines, benzodiazepines, caffeine, phenothiazines, and topical agents.

Physical therapy restoration

Modalities, when evaluated as unimodal therapy, may not show clear-cut evidence of effectiveness. However, they appear to be useful in combination which, unfortunately, makes statistical evaluation more difficult. Nonetheless, scientific rationale exists for some. Ice application with lowering of temperature is known to decrease nerve conduction to the point of anesthesia, and the inflammatory reaction is contained with a reduction of chronic changes.20,21 To be effective, the body part must be packed in ice for periods in excess of 30 minutes. Trigger point desensitization is indicated. Liberal use of ice is the preferred method of treatment. Heat does seem to soften muscle preparatory to stretching. An adjunct vapocoolant helps to block the stretch reflex and makes lengthening easier.

Mechanical traction is useful for certain specific indications. Conceptually, we apply traction to stretch muscle groups, not to distract the spine or to release nerve entrapment. We do not believe that distraction can be effected with the weights that are used, and the principle of entrapment is not tenable. Therefore, traditional pelvic or leg traction is not employed. Gravity traction is applied for iliopsoas contractures in the patient with a spinal flexion deformity and/or failure to extend the back. Autotraction is an important technique, which allows three-dimensional placement of the spine by rotating, flexing, or extending the unit as the patient imposes his or her own body force by pushing and pulling. The self-applied force of autotraction will not exceed that which could be potentially injurious, but it will release tight paraspinal muscles. Autotraction does not decompress the nerve root, as was the concept of its originators.22,23 Most stretching is manual and labor intensive, since it is important that the therapist feels the tissue during treatment.

Functional electrical stimulation

When a specific muscle group is weak, functional electrical neuromuscular stimulation and muscle reeducation are implemented.24,25 This technique can produce rapid and dramatic increases in muscle recruitment patterns and muscle strength; footdrop braces can be discarded. Functional electric stimulation (FES) is used when minimal muscle recruitment or reduced voluntary control are detected upon muscle testing. With FES, muscles can be strengthened ‘passively’ without placing excessive demands on the patient, especially in the presence of pain. FES is the process of applying an external electrical stimulus to a muscle or muscle groups in order to induce muscle contraction. We also use FES successfully to treat conversion-disorders-type paralysis, for electric testing of motor responses, and as a motor dysfunction treatment method. FES allows the induction of maximal muscular contraction without any voluntary effort on the part of the treated individual. This latter aspect is of value for patients with chronic pain whose pain is often aggravated through exercise or who are unable to initiate voluntary effort necessary for muscular conditioning due to disuse. Studies on FES indicate that this passive intervention strategy can be quite effective.25 It should be emphasized here that FES is not a substitute for regular exercise. FES is used to ‘jump start’ the neuromuscular system. Once the patient has gained sufficient power to initiate voluntary movement comfortably, the patient engages in active resistive exercises for strengthening and endurance training.

Motor dysfunction treatment

Motor dysfunction treatment (MDT) is incorporated into regular patient treatment to address problems such as depressed muscle activity, increased muscle tension (hyperactivity), significant EMG asymmetry or asynchrony, and nondistinctive EMG activity patterns (work versus rest cycles). For example, in order to restore function to muscle with depressed EMG activity, the MDT protocol will consist of monitoring the target muscle while the patient performs selected therapeutic maneuvers designed to recruit that muscle compared to its contralateral partner. If EMG recruitment is found to be minimal, functional electrical stimulation is used to increase strength and power of the affected muscle. As soon as the patient demonstrates ability to recruit the muscle(s) voluntarily, active EMG interventions using methods of muscle reeducation and biofeedback commence.

Postural correction

Awkward postures cause fatigue, strain, and eventually pain; they need to be corrected. Poor postures will result in pain, loss of stability, and falls.26 Faulty posture and poor body alignment develop slowly and may not be apparent to the individual. Poor posture is found with obesity, leading to weakened muscles, emotional tension, and poor body attitudes in the workplace. The incidence of pain increases in predominantly sitting work activities, especially with the use of computers. Ideally, patients do best when they can alternate activities among walking, standing, and sitting.27

It is recognized that when the body is not in correct alignment, static loading on muscles and joints results in awkward positions that are not healthy.26 Prolonged forward bending of the head and trunk, stooped postures, forced postures, and postures causing constant deviation from neutral alignment are but a few examples of poor postures. Even sleeping postures must be assessed.28

Job simulation and work readiness

Workplace design

This type of ergonomic intervention aims at assessing the relationship between human characteristics (e.g. posture, body mechanics) and musculoskeletal stresses with emphasis on work issues.29 The task of the ergonomist is to assist the patient or employer to design or modify the workstation to insure proper engineering design and good body mechanics when performing job tasks.

A tool which we have used in the process of analyzing and recommending workplace adjustments and modifications is Sitting Workplace Analysis and Design (SWAD).30 SWAD is a computer program resembling artificial intelligence. The inputs to the program are workplace user demographics, 16 anthropometric dimensions, workplace dimensions, work tools, and the priority and frequency of use of each work element. SWAD then combines this information with a ‘knowledge base’ of ergonomic principles and guidelines and a set of inference procedures. The output of SWAD is the recommended workplace dimensions, heights, reaches, footrest, chair parameters, VDT parameters, and optimal placement of all work tools. It enables customization of workstation adjustment without trial and error.

Electromyogram biofeedback

A carefully processed EMG signal can be a useful tool in the quantitative measurement of muscular performance, for reeducation and in the evaluation of patient’s response to specific treatments.17 Biofeedback is the process of using specialized instruments to give people information about their biological systems (temperature, heart rate, muscle activity, etc.). It is a set of training techniques used to increase awareness and voluntary control of biological conditions and relate them to human physical and emotional well-being. Biofeedback (BF) is useful in the relief of stress, tension, headaches, muscular dysfunction, and for the reduction of muscle tension, which correlates well with a reduction in pain and improvement of muscle strength.31,32

Behavioral modification

Patients with chronic pain perceive their pain as a disability limiting their functional status. The perception of pain as a disability is such a national problem that the Social Security Administration Commission on the Evaluation of Pain recommended the development of a listing ‘impairment due primarily to pain.’33

An abnormal psychological profile is inherited by the treatment team, insurer, and all others concerned. Our study of pain-population patients found 62.5% to have anxiety disorders and 56.2% to have current depression.34 These conditions were comingled with other less prevalent disorders. Only 5.3% of 283 patients were found to have no psychiatric diagnosis. Pure psychogenic pain is probably rare when presented as mental events giving rise to pain. However, all pain, as perceived by the patient, is real, regardless of cause. Most bodily pain is a combination of factors, e.g. physical stimuli and mental events. Abnormal mental and emotional states may arise from a background of past personal experiences with pain, or from personality characteristics. A history of physical abuse is not uncommon in patients with chronic pain.

The behavioral staff address the ‘fall out’ and behavioral responses to tapering from narcotics. Intense activation will produce endorphin release that helps ameliorate withdrawal.35 Most important of all, we do not teach people how to live or cope with their pain. Our goal is reduction or elimination of pain, and for the patient, to control any painful flare-ups. The pain is thereby no longer catastrophic; hence, it does not control the patient’s life.

Role of psychiatry

Patients with chronic pain being treated at pain centers have been reported to suffer a wide range of psychiatric conditions. These include depression, anxiety, drug dependence/abuse, irritability and/or anger, physical or sexual abuse, suicidal or homicidal ideation, and memory or concentration problems. These data are supported by epidemiological community studies, which indicate a strong relationship between chronic pain and depression.36–39

Depression is not only a potential target for treatment, but coping strategies may differ in depressed patients with chronic pain. Patients with chronic pain may over-rely on passive avoidance coping activities in response to life’s stresses, including pain; these coping activities may be a function of depressed mood.40

Drug abuse, dependence, and addiction are reported in the range of 3.2–18.9%.41 These diagnoses are reported in a significant percentage of chronic pain patients, but evidence of addictive behaviors is not common. The dependence occurs as a result of the pain, not addiction. At issue is whether patients with physician-perceived drug problems are best treated at a pain treatment facility or at a substance abuse facility. Detoxification in pain treatment facilities where simultaneous pain treatment is available appears to be the better route.37 Detoxification is not realistic unless pain alleviation occurs simultaneously. Management of pain medications and controlled substances should parallel physical and functional restoration.

HEADACHES AND PAIN REHABILITATION

Headache is a frequent comorbid condition in patients with chronic pain. These headaches are mostly classified as migraines. However, a considerable number of patients with chronic pain present with injury-related headaches. In one study,42 10.5% of the chronic pain patients had headache interfering with function. Of these, 55.8% related their headaches to an injury and 83.7% had neck pain. Migraine headache was most common (90.3%) with cervicogenic being second (33.8%). Of the total, 44.2% had more than one headache diagnosis. The most frequent headache precipitants were mental stress, neck positions, and physical activity utilizing the neck muscles. Of the total group, 74.6% had a neck tender point. Discriminate analysis found the following symptoms as the most common predictors of headache: (1) onset of severe headache beginning at the neck tender point and numbness in arms and legs; (2) headache brought on by neck positions and arms overhead; and (3) cervical pain with a tender point in the neck. Taut muscle bands and cervical tender/trigger points perpetuate head and neck pain. Successful rehabilitation efforts must address both the headache component through effective medications and physical medicine management of the cervical abnormality.

GERIATRIC PAIN REHABILITATION

While generally thought of as a worker compensation injury-related model, the concept of pain rehabilitation applies to patients of all age groups. As American workers age, the number of expected disabled workers is also expected to increase. Older workers and those who do become disabled can respond well to well-designed, customized programs tailored to their levels, goals, and expectations.43 Many studies have reported significant improvement in functional abilities of patients with pain irrespective of their age group.30,44,45 Even when the outcome of return to work in older patients was not achieved (e.g. Mayer and Gatchel4), the consensus is that older patients should not be denied access to pain rehabilitation after onset of injury.30

OUTCOME EVALUATION OF THE PAIN REHABILITATION MODEL

Are multidisciplinary pain centers effective? The answer is ‘yes,’ by virtue of increase in functional activity, return to work, decreased use of the healthcare system, elimination of opioid medication, closure of disability claims, pain reduction, and proved cost-effectiveness.46 Evidence from well-designed outcome studies indicates that: (1) multidisciplinary pain facilities do return patients with chronic pain to work; (2) the increased rates of return to work are due to treatment; and (3) the benefits of treatment are not temporary.2,47–49

In one study, our center reported that 86% of all patients treated returned to full activity, with 70% fully employed and another 16% who were physically capable of full employment but could not return to work because jobs were not available.50 Among the 86% who were fully active, there was no clear-cut difference between compensation and noncompensation class cases.14 In a more recent study, the return rate to full function and work was again 86%, albeit the patients had some residual discomfort that eventually remitted or was controlled at a low level of intensity.2 The 14% who failed to return to full function were highly complex patients with major behavioral problems.

1 Rosomoff RS. The pain patient. State of the Art Reviews. Spine. 1990;5(3):417-428.

2 Cutler RB, Fishbain D, Rosomoff HL, et al. Does nonsurgical pain center treatment of chronic pain return patients to work? A review and meta-analysis of the literature. Spine. 1994;19:643-652.

3 Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. A rehabilitation physical medicine perspective. Cohen MJM, Campbell JN, editors. Pain treatment centers at a crossroads: a practical and conceptual reappraisal, progress in pain research and management. Ch. 4, vol. 7.. IASP Press, Seattle, 1996;47-58.

4 Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. Effect of age on outcomes of tertiary rehabilitation for chronic disabling spinal disorders. Spine. 2001;26(12):1378-1384.

5 Rosomoff HL, Fishbain D, Goldberg M, et al. Physical findings in patients with chronic intractable benign pain of the back and/or neck. Pain. 1989;37:279-287.

6 Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. Comprehensive multidisciplinary pain center approach to the treatment of low back pain. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991;2(4):877-890.

7 Rosomoff HL. Do herniated disks produce pain? Clin J Pain. 1985;1:91-93.

8 Wall PD. Physiological mechanisms involved in the production and relief of pain. In: Bonica JJ, Procacci P, Pagni CA, editors. Recent advances on pain: pathophysiology and clinical aspects. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1974:36-63.

9 Vane JR. Pain of inflammation: an introduction. Bonica JJ, Lindblom U, Iggo A, editors. Advances in pain research and therapy, vol. 5.. Raven Press, New York, 1983;597-603.

10 Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. Assessment and treatment of chronic low back pain: the multidisciplinary approach. In: Rucker KS, Cole AJ, Weinstein SM, editors. Low back pain: a symptom-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2000:343-362.

11 Spitzer WO, LeBlanc FE, Dupuis M, et al. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders: a monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Spine. 1987;12:51-59.

12 Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1983.

13 Abdel-Moty E, Khalil T, Steele-Rosomoff R, et al. Maximizing progress during low back pain rehabilitation. In: Nielsen R.V., Jorgensen K, editors. Advances in industrial ergonomics and safety. London: Taylor & Francis; 1993:331-335.

14 Rosomoff HL, Green CJ, Silbret M, et al. Pain and low back rehabilitation program at the University of Miami School of Medicine. In: Ng LKY, editor. New approaches to treatment of chronic pain: a review of multidisciplinary pain clinics and pain centers. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph Series 36. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office; 1981:92-111.

15 Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. Myofascial pain syndromes. In: Follett KA, editor. Neurosurgical pain management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004:57-72.

16 Headley B. Assessing muscle dysfunction from active trigger points. Adv Physical Therap. 1997;8:21-22.

17 Khalil TM, Abdel-Moty E, Diaz E, et al. Electromyographic symmetry pattern in patients with chronic low back pain and comparison to controls. In: Karwowski W, Yates JW, editors. Advances in industrial ergonomics & safety, III. London: Taylor and Francis; 1991:483-490.

18 Fishbain DA, Turner D, Rosomoff H, et al. Millon Behavioral Health Inventory scores of patients with chronic pain associated with myofascial pain syndrome. Pain Med. 2001;2:1328-1335.

19 Steele-Rosomoff R, Rosomoff HL, Abdel-Moty E. Vocational rehabilitation and ergonomics. In: Burchiel KJ, editor. Surgical management of pain. New York: Thieme; 2001:171-180.

20 Rosomoff HL. The effects of hypothermia on the physiology of the nervous system. Surgery. 1956;40:328-336.

21 Rosomoff HL, Clasen RA, Hartstock R, et al. Brain reaction to experimental injury after hypothermia. Arch Neurol. 1965;13:337-345.

22 Lind GAM. Auto-traction: treatment of low back pain and sciatica. Sweden: Sturetryckeriet, 1974.

23 Natchev E. A manual on autotraction treatment for low back pain. Folksam Scientific Council Publ, B. 1984:171.

24 Abdel-Moty E, Khalil TM, Rosomoff RS, et al. Computerized electromyography in quantifying the effectiveness of functional electrical neuromuscular stimulation. In: Asfour SS, editor. Ergonomics/human factors, IV. New York: Elsevier Science; 1987:1057-1065.

25 Abdel-Moty E, Fishbain D, Goldberg M, et al. Functional electrical stimulation treatment of postradiculopathy associated muscle weakness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:680-686.

26 Khalil TM, Abdel-Moty E, Rosomoff RS, et al. Ergonomics in back pain. A guide to prevention and rehabilitation. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1993;81-86.

27 Khalil TM, Abdel-Moty E, Steele-Rosomoff R, et al. The role of ergonomics in the prevention and treatment of myofascial pain. In: Rachlin ES, editor. Diagnosis and comprehensive treatment of myofascial pain: handbook of trigger point management. New York: Mosby Year Book; 1993:487-523.

28 Khalil TM, Abdel-Moty E, Steele-Rosomoff R, et al. The role of ergonomics in the prevention and treatment of myofascial pain. In: Rachlin ES, editor. Diagnosis and comprehensive treatment of myofascial pain: handbook of trigger point management. New York: Mosby Year Book; 1993:487-523.

29 Khalil TM, Abdel-Moty E, Steele-Rosomoff R, et al. Ergonomic programs in post injury management. In: Karawowski W, Marras WS, editors. The occupational ergonomics handbook. New York: CRC Press; 1999:1269-1289.

30 Abdel-Moty E, Khalil TM, Rosomoff RS, et al. Ergonomics considerations and interventions. In: Tollison CD, Satterthwaite JR, editors. Painful cervical trauma: diagnosis and rehabilitative treatment of neuromusculoskeletal injuries. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 1990:214-229.

31 Asfour SS, Khalil TM, Waly S, et al. Biofeedback in back muscle strengthening. Spine. 1990;15(6):510-513.

32 Khalil T, Asfour SS, Waly SM, et al. Isometric exercise and biofeedback in strength training. In: Asfour SS, editor. Trends in ergonomics/human factors, IV. New York: Elsevier Science; 1987:1095-1101.

33 Turk DC, Rudy TE, Stieg RL. The disability determination dilemma: towards a multi-axial solution. Pain. 1988;34:217-229.

34 Fishbain DA, Goldberg M, Meagher R, et al. Male and female chronic pain patients categorized by DSM-III psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Pain. 1986;26:181-197.

35 Carr DB, Bullen BA, Skrinar GS, et al. Physical conditioning facilitates the exercise-induced secretion of beta-endorphin and beta-hypoprotein in women. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:560-563.

36 Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff HL, et al. Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clin J Pain. 1997;13(2):116-137.

37 Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Pain facilities: a review of their effectiveness and referral selection criteria. Psychiatr Manage Pain. 1997;1(2):107-116.

38 Fishbain DA. Somatization, secondary gain, and chronic pain: Is there a relationship? Curr Rev Pain. 1998;6:101-108.

39 Fishbain DA, Cutler BR, Rosomoff HL, et al. Comorbidity between psychiatric disorders and chronic pain. Psychiatr Manage Pain. 1998;2(1):1-10.

40 Weickgerant AL, Slater MA, Patterson TL, et al. Coping activities in chronic low back pain: relationship with depression. Pain. 1993;53:95-103.

41 Fishbain DA, Steele-Rosomoff R, Rosomoff HL. Drug abuse, dependence, and addiction in chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1992;8:77-85.

42 Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Cole B, et al. International Headache Society headache diagnostic patterns in pain facility patients. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:178-193.

43 Khalil TM, Abdel-Moty E, Zaki AM, et al. Reducing the potential for fall accidents among the elderly through physical restoration. In: Kumar S, editor. Advances in industrial ergonomics & safety, IV. London: Taylor & Francis; 1992:1127-1134.

44 Khalil TM, Abdel-Moty E, Diaz E, et al. Efficacy of physical restoration in the elderly. Experimental Aging Research. 1994;20(3):189-199.

45 Cutler RB, Fishbain DA, Lu Y, et al. Prediction of pain center treatment outcome for geriatric chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1994;10(1):10-17.

46 Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain centers in the treatment of chronic pain. Cohen MJM, Campbell JN, editors. Pain treatment centers at a crossroads: a practical and conceptual reappraisal. Progress in pain research and management, vol. 7.. IASP Press, Seattle, 1996;257-273.

47 Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Movement in work status after pain facility treatment. Spine. 1996;21(2):2662-2669.

48 Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff HL, et al. Impact of chronic pain patients’ job perception variables on actual return to work. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:197-206.

49 Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Pain facility treatment outcome for failed back surgery syndrome. Curr Rev Pain. 1999;3:10-17.

50 Cassisi JE, Sypert GW, Salamon A, et al. Independent evaluation of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program for chronic low back pain. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:877-883.

Abdel-Moty E, Fishbain D, Khalil T, et al. Functional capacity and residual functional capacity and their utility in measuring work capacity. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:168-173.

American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain 2003; 73.

Fishbain DA, Rosomoff HL, Cutler B, et al. Opiate detoxification protocols. A clinical manual. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1993;5(1):53-65.

Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff RS, et al. The problem-oriented psychiatric examination of the chronic pain patient and its application to the litigation consultation. Clin J Pain. 1994;10:28-51.

Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Validity in self-reported drug use in chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:3184-3191.

Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Does the Conscious Exaggeration Scale detect deception within patients with chronic pain alleged to have secondary gain? Pain Med. 2002;3:139-146.

Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Are opioid-dependent/tolerant patients impaired in driving-related skills? A structured evidenced-based review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(6):559-577.

Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Is pain fatiguing? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2003;4(1):51-62.

Gunn CC. Treatment of chronic pain intramuscular stimulation for myofascial pain of radiculopathic origin, 2nd edn., New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:165.

Khalil TM, Goldberg ML, Asfour SS, et al. Acceptable maximum effort (AME): a psychophysical measure of strength in back pain patients. Spine. 1987;12(4):372-376.

Khalil TM, Asfour SS, Martinez LM, et al. Stretching in the rehabilitation of low-back pain patients. Spine. 1992;17(3):311-317.

Moty EA, Khalil T, Asfour S, et al. On the relationship between age and responsiveness to rehabilitation. In: Das B, editor. Proceedings of the Annual International Industrial Ergonomics and Safety Conference. Advances in Industrial Ergonomics and Safety 11. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis; 1990:49-56.

Rosomoff HL, Fishbain DA, Goldberg M, et al. Are myofascial pain syndromes (MPS) physical findings associated with residual radiculopathy?. Pain. 1990;Suppl 5:S396.

Rosomoff RS, Rosomoff HL. Hospital-based inpatient treatment programs. In: Tollison CD, editor. Handbook of pain management, Ch. 51. 2nd edn. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:686-693.

Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS, Fishbain D. Chronic low back pain. J Back Musculoskel Rehab. 1997;9(3):201-208.

Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS, Fishbain DA. Types of pain treatment facilities referral selection criteria: are they medically & cost effective? J Florida Med Assoc. 1997;84(1):41-45.

Rosomoff HL, Steele-Rosomoff R. Surgery for the herniated lumbar disk with nerve root entrapment; are alternative treatments to surgical intervention effective? Curr Rev Pain. 1998;2:121-129.

Steele-Rosomoff R, Rosomoff HL. Hospital-based inpatient treatment programs. In: Tollison CD, Satterwaite JR, Tollison JW, editors. Practical pain management, Ch. 53. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:782-790.

US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. Selected characteristics of occupations defined in the DOT. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1981.

US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. Dictionary of occupational titles, 4th edn. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1986.

Yeomans SG, Liebenson C. Applying outcomes management to clinical practice. JNMS. 1997;5(1):1-14.