History and Examination

HISTORY

The history is the most important part of the neurological evaluation. Just as detectives gain most information about the identity of a criminal from witnesses rather than from the examination of the scene of the crime, neurologists learn most about the likely pathology from the history rather than the examination.

The general approach to the history is common to all complaints. Which parts of the history prove to be most important will obviously vary according to the particular complaint. An outline for approaching the history is given below. The history is usually presented in a conventional way (below) so that doctors being informed of or reading the history know what they going to be told about next. Everyone develops their own way of taking a history and doctors often adapt the way they do it depending on the clinical problem facing them. This section is organised according to the usual way in which a history is presented—recognising that sometimes elements of the history can be obtained in a different order.

Many neurologists would regard history taking, rather than neurological examination, as their special skill (though you obviously need both). This indicates the importance attached to history taking within neurology, and reflects that it is an active process, requiring listening, thinking and reflective questioning rather than simply passive note taking. There is now evidence that it is not just what the patient says, but the way he says it that can be diagnostically useful (for example in the diagnosis of non-epileptic attack disorder).

The neurological history

• Age, sex, handedness, occupation

• History of present complaint

Basic background information

Establish some basic background information initially—the age, sex, handedness and occupation (or previous occupation) of the patient.

Handedness is important. The left hemisphere contains language in almost all right-handed individuals, and in 70% of patients who are left-handed or ambidextrous.

Present complaint

Start with an open question such as ‘Tell me all about it from the very beginning’ or ‘What has been happening?’. Try to let patients tell their story in their own words with minimum interruption. The patient may need to be encouraged to start from the beginning. Often patients want to tell you what is happening now. You will find this easier to understand if you know what events led up to the current situation.

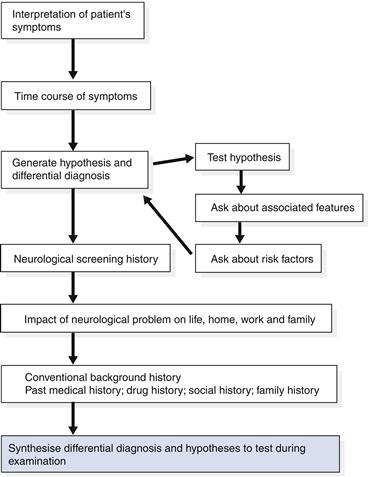

Whilst listening to their story, try to determine (Fig. 1.1):

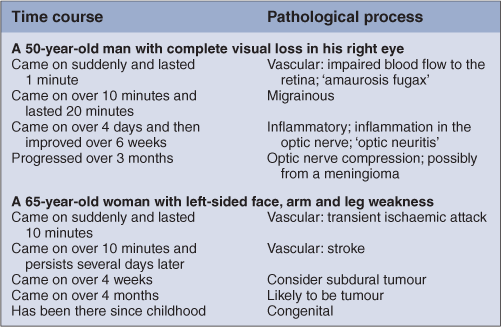

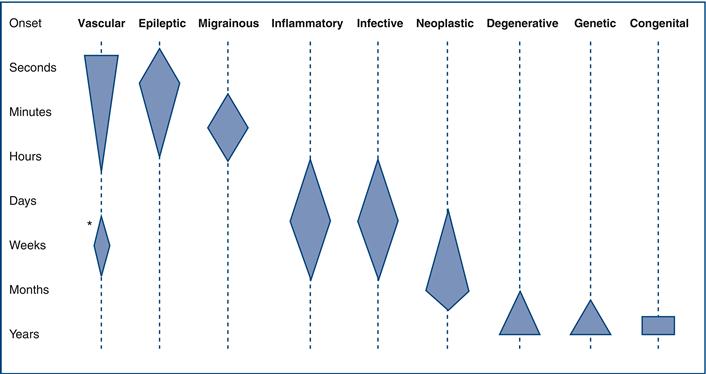

• The time course. This tells you about the tempo of the pathology (Table 1.1 and Fig. 1.2).

– The pattern: If intermittent, what was its duration and what was its frequency?

Figure 1.1 Flow chart: the present complaint

Also determine:

Conventional history

Past medical history

This is important to help understand the aetiology or discover conditions associated with neurological conditions. For example, a history of hypertension is important in patients with stroke; a history of diabetes in patients with peripheral neuropathy; and a history of previous cancer surgery in patients with focal cerebral abnormalities suggesting possible metastases.

It is always useful to consider the basis for any diagnosis given by the patient. For example, a patient with a past medical history that starts with ‘known epilepsy’ may not in fact have epilepsy; once the diagnosis is accepted, it is rarely questioned and patients may be treated inappropriately.

Drug history

It is essential to check what prescribed drugs and over-the-counter medicines are being taken. This can act as a reminder of the conditions the patient may have forgotten (hypertension and asthma). Drugs can also cause neurological problems—it is often worth checking their adverse effects.

N.B. Many women do not think of the oral contraceptive as a drug and need to be asked about it specifically.

Family history

Many neurological problems have a genetic basis, so a detailed family history is often very important in making the diagnosis. Even if no one in the family is identified with a potentially relevant neurological problem, information about the family is helpful. For example, think about what a ‘negative’ family history means in:

The former might well have a familial problem though the family history is uninformative; the latter would be very unlikely to have an inherited problem.

In some circumstances, patients can be reluctant to tell you about certain inherited problems: for example, Huntington’s disease. On other occasions, other family members can be very mildly affected; for example, in the hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies, some family members will simply be aware that they have high arched feet, so this needs to be actively sought if it is likely to be relevant.

Social history

Neurological patients frequently have significant disability. For these patients, the environment in which they normally live, their financial circumstances, their family and carers in the community are all very important to their current and future care.

Toxin exposure

It is important to establish any exposure to toxins, including in this category both tobacco and alcohol, as well as industrial neurotoxins.

Systemic inquiry

Systemic inquiry may reveal clues that general medical disease may be presenting with neurological manifestations. For example, a patient with atherosclerosis may have angina and intermittent claudication as well as symptoms of cerebrovascular disease.

Patient’s perception of illness

Ask patients what they think is wrong with them. This is useful when you discuss the diagnosis with them. If they turn out to be right, you know they have already thought about the possibility. If they have something else, it is also helpful to explain why they do not have what they suggested and probably are particularly concerned about. For example, if they have migraine but were concerned that they had a brain tumour, it is helpful to discuss this differential diagnosis specifically.

Anything else?

Always include an open question towards the end of the history—‘Is there anything else you wanted to tell me about?’—to make sure patients have had the chance to tell you everything they wanted to.

Synthesis of history and differential diagnosis

It is useful to summarise the history before moving on to the examination—in your own mind at least—and try to come to a differential diagnosis. The type of differential diagnosis will vary according to the patient—some examples:

If you think about the differential at this stage, you can then be sure to use the examination to try to come to a diagnosis.

So, think about the differential diagnosis generated from the history. Think what might be found on examination in these circumstances and ensure you focus on these possibilities during your examination.

In summary, think about the history.

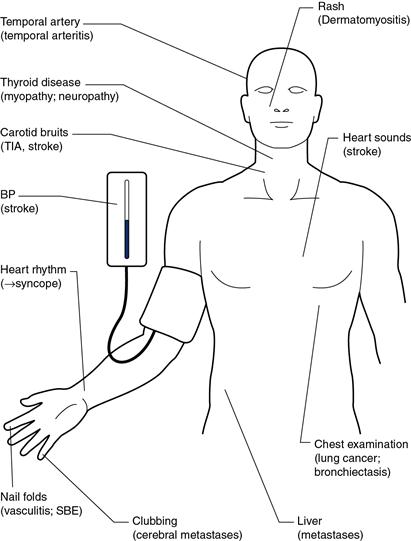

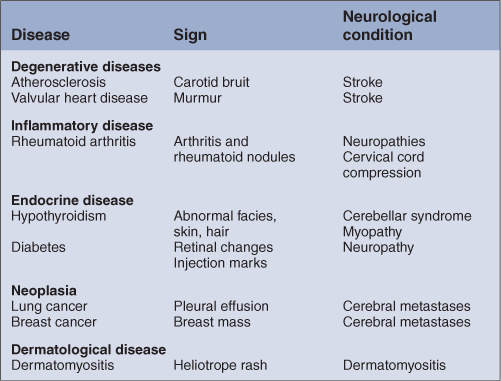

GENERAL EXAMINATION

General examination may yield important clues as to the diagnosis of neurological disease. Examination may find systemic disease with neurological complications (Fig. 1.3 and Table 1.2).

A full general examination is therefore important in assessing a patient with neurological disease. The features that need to be particularly looked for in an unconscious patient are dealt with in Chapter 27.

TIP

TIP TIP

TIP TIP

TIP

TIP

TIP