Chapter 5 History and Examination

Taking the history

Women may find discussing gynaecological symptoms difficult and require

| Privacy | Time | Sympathy |

|---|---|---|

| The consultation should be held in a room with adequate facilities and privacy. Permission should be sought for any students who are present | The patient should be allowed to tell her own story before any attempt is made to elicit specific symptoms | The doctor’s manner must be one of interest and understanding |

| Standard history taking | Additional features relevant to gynaecology |

|---|---|

| Age | Parity |

| Presenting complaint | Obstetric history |

| Past medical history | Contraception and fertility requirements |

| Medication history | Smear history |

| Allergies | Menstrual history – this will often be part of the presenting complaint |

| Social history | |

| Family history | |

| Systemic enquiry |

Useful definitions

Menarche – first menstrual period.

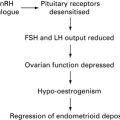

Menopause – date of final menstrual period. This can only be defined with certainty after a year has elapsed since the final menstrual period. It is also useful to ask about menopausal symptoms and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) use. The classic menopausal symptom is vasomotor flushes, but a myriad of other symptoms can also be experienced (see Chapter 18 The Menopause).

Abnormal Bleeding

Postcoital bleeding – bleeding occurring after intercourse.

Intermenstrual bleeding – bleeding between periods.

Postmenopausal bleeding – bleeding more than one year since LMP.

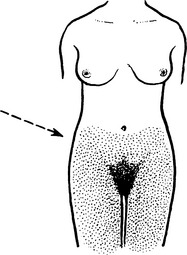

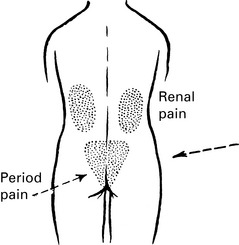

Pelvic pain

Primary dysmenorrhoea – periods have been painful since established menstruation has occurred.

Other Gynaecolgical Symptoms

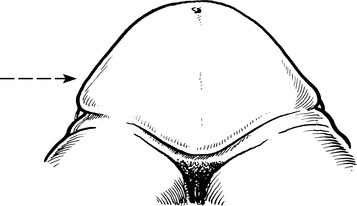

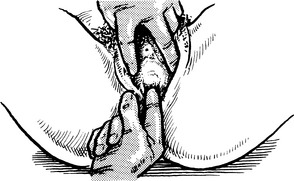

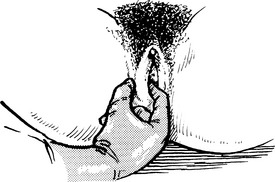

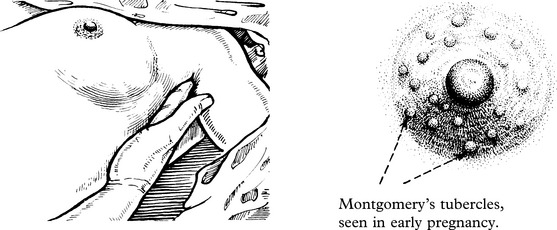

Examination of the vulva

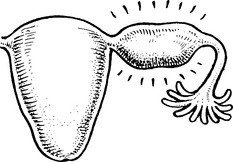

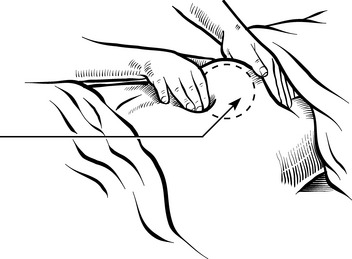

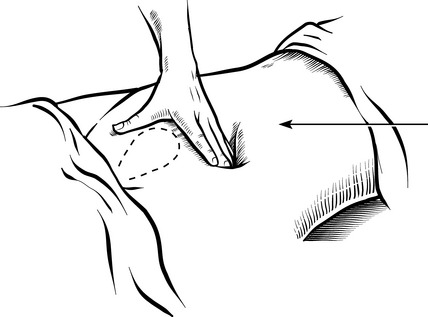

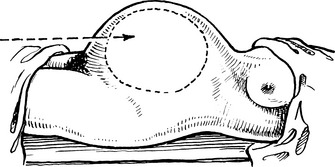

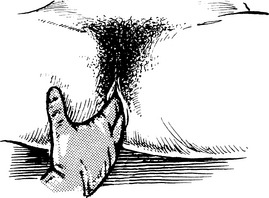

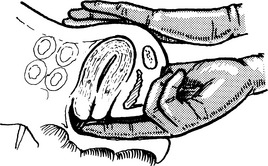

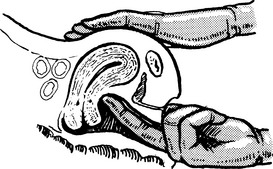

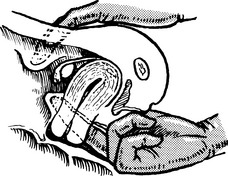

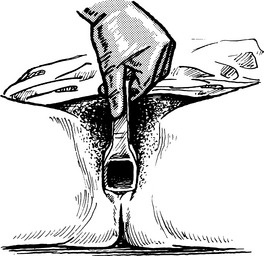

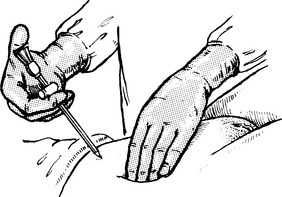

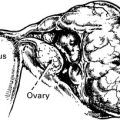

Bimanual pelvic examination

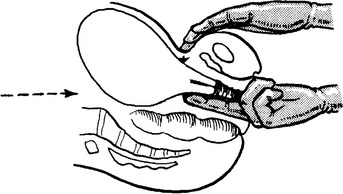

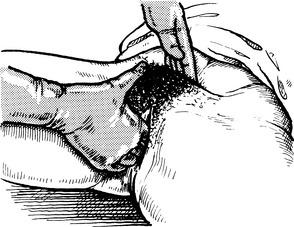

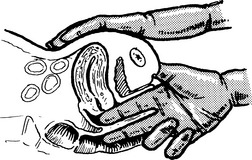

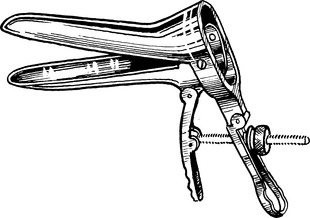

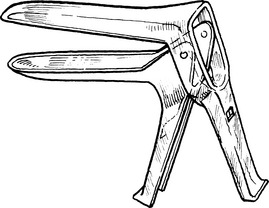

Speculum examination

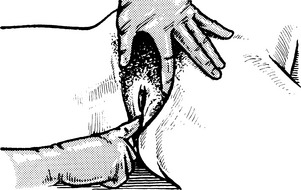

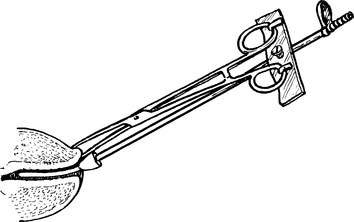

SIMS’ SPECULUM (the duckbill speculum) is designed to hold back the posterior vaginal wall so that air enters the vagina because of negative intra-abdominal pressure, and the anterior wall and cervix are exposed.