1 History and background of traditional Chinese medicine in neurological conditions

Zang Fu, the origins of physiology

Firstly we will give a quick explanation of the major functions of the Zang Fu organs. These functions are seen as inextricably linked and interdependent and lead to TCM diagnoses of some complexity. We are indebted to Worsley, an influential Western teacher and practitioner (and also originally a physiotherapist) for some useful ideas about the Zang Fu organs in general [1]. Most texts offer two lists of six pairs of organs, some functions of which correspond to those understood by Western medicine and some which plainly do not (Table 1.1).

| Zang organs (Yin) | Fu organs (Yang) |

|---|---|

| Heart (Xin) | Small Intestine (Xiao Chang) |

| Lungs (Fei) | Large Intestine (Da Chang) |

| Liver (Gan) | Gall Bladder (Dan) |

| Spleen (Pi) | Stomach (Wei) |

| Kidney (Shen) | Urinary Bladder (Pang Guan) |

| Pericardium (Xin Bao) | Sanjiao |

|---|---|

| (Extra Uterus) | (Extra Brain) |

Heart (Xin)

The connection between the Heart and the emotions is well understood in folk legend in most countries but there is little scientific proof that this could have any foundation. However there are some interesting ideas in a paper by Rosen [2], where the internal memory of the heart cells with regard to physiological process is recognized and discussed. It is suggested that the heart does remember, ‘making use of mechanisms similar to those in other systems that manifest memory, the brain, the gastrointestinal tract and the immune system’.

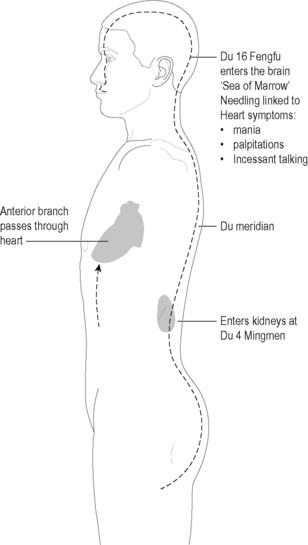

Since the Du meridian is also closely associated with the Kidneys at Du 4 or Mingmen, both these points can be used to influence Heart function (Figure 1.1).

Lungs (Fei)

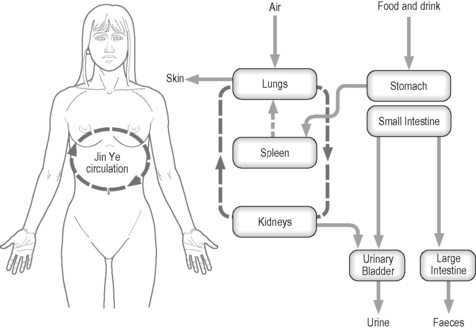

The Lungs control respiration and are responsible for the intake of clean air, which they convert into ‘Clear Qi’. Together with the Qi produced from substances that are eaten and drunk, this goes to make up the Post Heaven or renewable Qi within the body. The rhythm of the Lungs sets the rate for all other body functions, starting with the first breath taken by the newborn baby. The clean air or Qi from the Lungs condenses into fluid and passes down through the Sanjiao to the Kidneys, where it is heated, vaporizes and ascends to the Lungs again, forming a sort of energy cycle effectively controlling water circulation within the body (Figure 1.2).

Liver (Gan)

Some authorities describe this as a rhythm, similar to that of the Lungs, but differing in that it is a voluntary rhythm depending on the circumstances [3]. Ideas of fight and flight, as understood in Western neurology, are clearly appropriate here.

Liver Qi should flow freely in all directions. If it is constrained it is said to invade the Stomach, Spleen or Lung. ‘Liver invading Spleen’ is fast becoming a common modern syndrome, perhaps because of the combined effect of unsuitable diet and stress on the liver triggering a chain reaction throughout the Zang Fu [4]. The Liver functions as a gentle regulator of the Spleen and Stomach and is thus a regulator of digestion. In addition, bile, under the control of the Liver, aids in the digestive process.

Spleen (Pi)

In TCM the Spleen is regarded as the minister of agriculture, able to control and regulate the production and distribution of essential nourishment. The Spleen is said to govern transformation and transportation. It is the main digestive organ in TCM and responsible, along with the Stomach, for the breaking down or transformation of ingested food and drink and its subsequent transportation to the other sites in the body where it will be utilized. The Spleen is said to incorporate and then distribute Nutritive Essence in order to diminish or augment body mass [5]. It is responsible for forming and reconstituting the internal milieu, gathering and holding together the substance of the body.

Kidney (Shen)

If too much fluid accumulates in the lower Jiao (Figure 1.2), it stagnates, giving rise to swelling at the knees and ankles, gravitational oedema, abdominal bloating and, occasionally, puffiness beneath the eyes. The build-up of fluid will have a direct effect on the lungs and eventually the heart, leading to further swelling in the upper part of the body.

Pericardium (Xin Bao)

The Pericardium is closely related to the Heart; traditionally it is thought to shield the Heart from the invasion of External Pathogenic factors. It is also known as the Heart Protector. The ancient manuscripts, most particularly the Spiritual Pivot [6], do not grant the Pericardium true Zang Fu status, describing the Heart as the master of the five Zang and the six Fu. The Heart is considered to be the dwelling of the Shen and no Pathogen can be allowed past the barrier of the Pericardium in case the Heart is damaged and the Shen departs and death occurs. The Pericardium displays some of the characteristics of Xin Heart but is far less important, in that it only assists with the government of Blood and housing the Mind.

However, as stated earlier, Worsley considered the Pericardium more of a function than an entity and the points on the channel are often used to treat emotional problems, having a perceived cheering effect [1]. They are also frequently used for their sedative effect. The meridian is also used in treatment of the Heart but is considered to be a less intense form of therapy than the use of Heart points.

Fu organs

Gall Bladder (Dan)

when the Liver constantly plans, and the Gall Bladder is constantly indecisive, by being bent over without stretching, and holding anger that is not discharged, the Heart blood grows dryer by the day. Spleen humor does not move and phlegm then confounds the orifices of the Heart, forming Heart Wind [7].

Stomach (Wei)

The link between digestion and the mental state has often been considered in the West and common sense tells us that one affects the other. It is rare to see it considered from the Chinese perspective, however, and an article by McMillin et al. [8] throws some light on the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve connections, which serve to reinforce the Zang Fu attributes.

Sanjiao

The Sanjiao is really the summary of the physiology of the Zang Fu organs and points on that meridian (designated Triple Energizer, or TE, by the World Health Organization) can be utilized in coordination of function, particularly fluid circulation. Figure 1.2 shows the contents of the three Jiaos with the predominant direction of Qi flow. In fact all the Zang Fu organs are interlinked in some way, either by fluid circulation or Qi production, so any diagram can become very complex once every factor is taken into account.

Zang Fu in neurology

The link between Chinese medicine and the brain is tenuous at best. As defined within the Zang Fu system the brain is one of the Curious Organs, so called because they are hollow, resembling the Fu organs and also functioning as stores rather than excreting. The other recognizable organs in this group are the Uterus and the Gall Bladder. Also considered under this heading, however, are the bones, the circulation system of blood and bone marrow. As Ross notes: ‘These tissues, in their aspect as the Curious Organs, have relatively little theoretical or practical importance and are generally treated via other systems’ [9].

The Brain (Nao)

In more modern texts it is designated a true Zang Fu (although one of the Curious Organs) and allotted functions that correlate closely with what we understand from our modern studies [10].

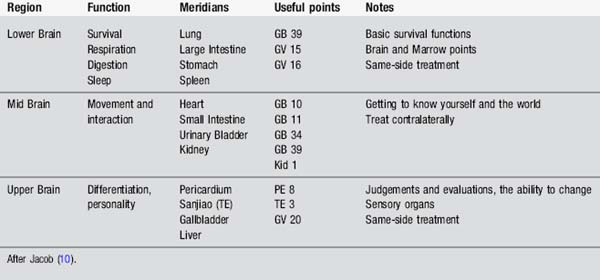

So the brain controls memory, concentration, motor activity and mental activity. It also controls the senses – sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch. Some texts also claim that Kidney Essence produces the Marrow which gathers to fill the brain and spinal cord, but this is rather a lazy way of thinking. If the brain can really be classified in the Zang Fu system then borrowing function from Western medicine is disingenuous at best. Nonetheless, one of the recent textbooks [10] has a wonderful list, owing its content to a cheerful mix of paradigms. Claiming that there are three parts to the brain, it characterizes function and offers selected acupoints, as shown in Table 1.2, giving somewhere to start in the general complexity.

Introducing the important syndromes

Bi syndrome

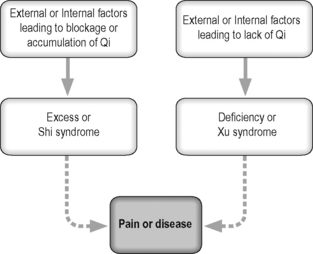

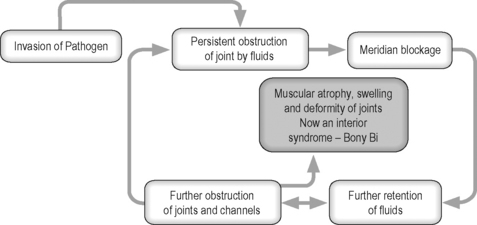

When Pathogenic factors invade the body they enter the most superficial meridians, particularly the Urinary Bladder and Small Intestine, and cause a general slowing of the flow. This affects both Qi and Blood. When fluids are slowed they tend to thicken, stagnate and become sticky. This process is the beginning of the formation of what is defined in TCM as Phlegm (Figure 1.3).

Wind Bi suggested points

All points to clear wind except BL 17 and BL 18, which nourish blood in order to expel the Pathogen.

Heat Bi suggested points

Use meridian end points, Spring, Well and Stream points.

All the forms of Bi syndrome discussed so far represent an acute type of condition, with the potential for leading to an excess internal syndrome (Figure 1.4).

Bi syndrome associated with Zang Fu organs

Vascular/Heart Bi

The following points may be used to relieve blood stasis:

Some of the above points could also be added to the local points used for the painful joint.

It is difficult to separate the circulation disturbances from abnormal blood pressure. Where acupuncture has been shown to decrease mean blood pressure significantly, it would seem a logical use of the intervention in this type of case [11]. A recent review investigating the actions of many complementary therapies in reducing high blood pressure came to the conclusion that acupuncture may have some value [12].

Antihypertensive drug therapy is efficient and reduces morbidity and mortality; however it is expensive and causes undesirable side-effects in some patients. Acupuncture effectively lowered both systolic and diastolic blood pressure after 6 weeks of TCM acupuncture in a recent study; however the effect did not outlast the duration of the treatment [13]. More work is anticipated in this field.

Muscle/Spleen Bi

As in the other categories, local and distal points to the affected joints are used.

Bone/Kidney Bi

The characteristic symptoms of soreness and pain in the joints are usually accompanied by stiffness and lack of mobility. Patients occasionally complain of heaviness in the affected limb. Kidney energies are said to decrease with advancing age so the fact that the joints and the spine tend to become stiff and limited in movement, resulting in the need to walk with some kind of artificial aid in this syndrome, tallies quite clearly with the universal picture of old age. There are many similarities between these symptoms and those of Parkinson’s disease (see Chapter 7). As is the way in most medicine, although some symptoms can be collected together in clear groups to form the syndromes, patients rarely present with such a clear pattern.

The Bi syndrome is a very interesting concept, based on the general idea that full body health is only possible if the Qi or vital energy found in the meridians and organs is able to move freely, flowing to where it is needed most and away from areas of pathological stagnation and concentration [14].

Wei Bi or atrophy syndrome

The theories informing a diagnosis of atrophy syndrome involve the invasion of Pathogenic Heat in the initial stages. This Heat dries up the body fluids and by doing so injures both the muscles and tendons. The original invasion also involves both the skin and the Lungs and manifests as a febrile disease (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 • Origin of Wei syndrome patterns.

(After Ross J. Zang Fu, The Organ System of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1984.)

Atrophy syndrome usually results directly from concentration of Exterior Heat in the Lungs, causing injury to body fluid. The general treatment principle will be to tonify Yin and Jin Ye or fluid balance. Most used are the Yang Ming meridians [15]. Stomach points are used for the lower limb and Large Intestine points for the upper limb. Qi deficiency of the Spleen and Stomach, often exacerbated by irregular food intake, can produce similar symptoms, such as weakness of the limbs, with movement impaired but still present. Often there will be indigestion with bloating and faecal frequency. The patient will dislike being cold and have a pale complexion. This can often be seen after a long debilitating illness.

Common TCM syndromes associated with Wei Bi

Feng syndromes

Some acupuncture authorities advise that any elderly person with numbness of the fingers, slightly slurred speech and a tongue showing any of the previously described colours should take immediate steps to avoid overwork, excessive stress and a poor diet. A short-term preventive measure would be direct Moxibustion on GB 39 Xuanzhong and ST 36 Zusanli [16].

Similar points to dispel wind, as in the case of wind Bi, mentioned earlier, can also be chosen. Some of the more effective are listed in Table 1.3.

| Point | Comment |

|---|---|

| LI 4 Hegu | Upper quadrant |

| LI 11 Quchi | Upper quadrant |

| LI 20 Yinxiang | Face |

| GB 20 Fengchi | Neck and shoulder |

| GB 21 Jianjing | Neck and shoulder |

| GB 31 Fengshi | Lower limb |

| GB 41 Zulinqi | Lower limb |

| BL 12 Fengmen | General |

| BL 62 Shenmai | Link to central nervous system/extra meridians |

| GV 20 Baihui | Link to central nervous system/extra meridians |

Summary

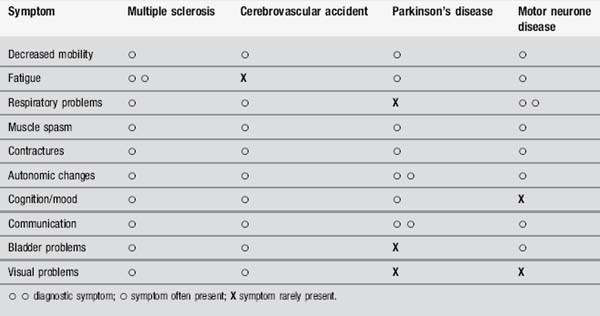

Very few patients are unlucky enough to suffer from all these problems but the nature of nerve damage implicit in the diagnosis of the condition means that they are all possible. Neurological conditions are often difficult to distinguish (with the possible exception of a straightforward stroke), because they have a great deal in common with one another. Table 1.4 shows the symptoms described above and how they relate to some of the diseases commonly treated by neurophysiotherapists.

It becomes evident that the treatment of cerebrovascular accident will not be dissimilar to that of MS, apart from the obvious problem of laterality, because the basic physiological functions within the body will need to be stimulated in similar ways. This is heresy to a neurology physiotherapist and quite possibly to a traditional acupuncturist too. However the staging proposed by Blackwell and MacPherson (see Chapter 8), will apply across the range of neurological problems, with minor adjustments, because it is firmly rooted in Zang Fu theory, which in itself regards organ physiology as function [17].

[1] Worsley J.R. Talking about Acupuncture in New York. England: Worsley, 1982.

[2] Rosen M.R. The heart remembers:clinical implications. Lancet. 2001;357:468-471.

[3] Larre C., Rochat de La Vallee E. The Secret Treatise of the Spiritual Orchid. London: Monkey Press, 2003;69.

[4] Maciocia G. The Foundations of Chinese Medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1989.

[5] Beinfeld H., Korngold E. Between heaven and earth. New York: Ballantine Books, 1992.

[6] Spiritual Pivot or Ling Shu. [Wu Jing-Nuan, Trans.]. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002.

[7] Dey T. Soothing the troubled mind. Brookline, Massachusetts: Paradigm Publications, 1999.

[8] McMillin D.L., Richards D.G., Mein E.A., et al. The Abdominal Brain and Enteric Nervous System. J Altern Complementary Med. 1999;5(6):575-586.

[9] Ross J., Zang Fu. The Organ System of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1984.

[10] Jacob J.H. The Acupuncturist’s Clinical Handbook, 5th ed. New York: Integrative Wellness, 2003.

[11] Yin C., Seo B., Park H.J., et al. Acupuncture, a promising adjunctive therapy for essential hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Neurol Res. 2007;29(Suppl. 1):S98-S103.

[12] Nahas R. Complementary and alternative medicine approaches to blood pressure reduction: An evidence-based review. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(11):1529-1533.

[13] Flachskampf F.A., Gallasch J., Gefeller O., et al. Randomized trial of acupuncture to lower blood pressure. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3121-3129.

[14] Hopwood V. Acupuncture in Physiotherapy. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2004.

[15] Xu H., Ni Y., Liu Y., et al. Diseases of Internal Medicine. Acupuncture Treatment of Common Diseases Based upon Differentiation of Syndromes. Beijing: The Peoples Medical Publishing House, 1988;243-250.

[16] Maciocia G. Wind-stroke. The Practice of Chinese Medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994;665-684.

[17] Blackwell R., MacPherson H. Multiple Sclerosis. Staging and patient management. Journal of Chinese Medicine. 1993;42:5-12.