CHAPTER 1 History and Anatomy

History

Gregory R.D. Evans and Elizabeth J. Hall-Findlay

Breast Reconstruction

The evolution of the use of autogenous tissue led to more options for women seeking reconstruction. Further, some women concerned about the use of implants turned to autogenous reconstruction as a viable alternative. Numerous techniques have evolved to allow for reconstruction using natural tissues. The earliest utilized muscles to provide blood flow to the skin and create a breast mound. The latissimus dorsi flap was the most popular form of autogenous tissue reconstruction in the 1970s. Although there are currently still limitations to this form of reconstruction, this option is still utilized today for patients seeking improved reconstructive outcomes.1–5

In 1982 the first transverse rectus abdominis flap (TRAM) flap procedure was performed. This transfer of the lower abdominal muscle, fat, and tissue improved the shape of the breast and allowed a more acceptable donor site for autogenous breast reconstruction. The flap has remained a workhorse for reconstruction but is still complicated by issues related to blood supply and donor site morbidity. As microsurgical techniques evolved, our ability to improve the vascular supply of the TRAM flap also increased. As our microsurgical skills improved, further refinements of flap harvest were performed. The goal was to continue to decrease the potential for donor site morbidity. Initial attempts included techniques of muscle sparing. This allowed the harvest of part of the rectus muscle while sparing other components, leaving the rectus muscle intact in certain locations. Perforator flaps were introduced in the late 1990s and early 2000s as a mechanism to decrease the abdominal donor site morbidity. The deep inferior epigastric perforator flap and the superficial inferior epigastric flap allowed transfer of these autogenous tissues while sparing the harvest of the rectus abdominis muscle. With improved microsurgical skills, additional locations for reconstruction were examined. The gluteal artery perforator flap allows the use of skin from the buttocks. The gracilis myocutaneous flap allows the use of skin and a portion of muscle from the inner thighs. The latissimus dorsi was again utilized without harvesting of muscle to supply bulk in the creation of a breast mound.1–5

Anatomy

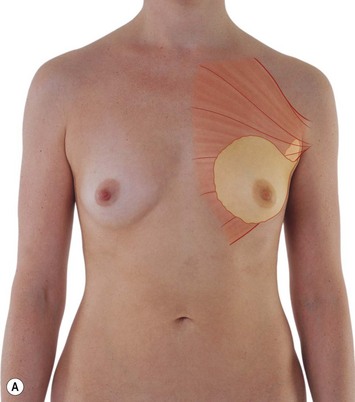

The adult female breasts lie on each side of the anterior thorax with their bases extending from about the second to sixth ribs.1–8 The breasts lie on a substantial layer of fascia overlying the pectoralis major muscle superomedially, the serratus anterior muscle in the lower third, and the anterior rectus sheath in the lower medial area. Although these appear to be the boundaries of the breast, the duct system often extends more widely than this. In about 15% of the cases, breast tissue extends below the costal margins. It is critical when performing breast reconstruction that the inframammary fold is maintained or at least identified and reconstructed if surgical removal of additional breast tissue below this fold is required. Considerable asymmetry is frequently found among normal women and the patient may not be aware of this asymmetry or may accept this as a normal variant. This is important to point out to the patient as autogenous reconstruction with preservation of the skin envelope may lead to further asymmetry postoperatively. One-half of the women have a volume difference of 10% or more and one-quarter have a volume difference of 20% or greater (Fig. 1.1).1

Fig. 1.1 Anterior view of breast.

From Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM, et al. Gray’s atlas of anatomy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

The precise position of the nipple–areola complex varies widely with the fat content of the breast and the age of the patient. In the nulliparous breast, the nipple position lies approximately 19–21 cm from the sternal notch.2 The amount of fat within the breast varies widely, as one would expect. The intimacy with which it is mixed with glandular tissue also varies. Microscopic examination demonstrates that the nipple is composed of the terminal ducts with a supporting stroma of smooth muscle that are mainly arranged in a circular fashion with a few arranged radially. Contraction of the circular muscles causes nipple projection; contraction of the radial fibers causes retraction.

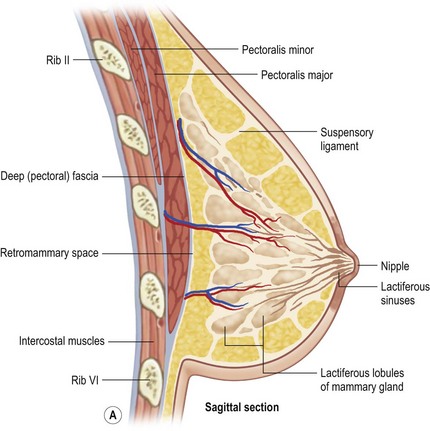

Breast tissue consists of lobes separated from each other by fascial envelopes, usually 15–20 in number. Each lobe is drained by a ductal system from which a lactiferous sinus opens on the nipple and each lactiferous sinus receives up to 40 lobules. Each lobule contains 10–100 alveoli which comprise the basic secretory unit (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2 Lateral view and sagittal section of breast.

From Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM, et al. Gray’s atlas of anatomy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

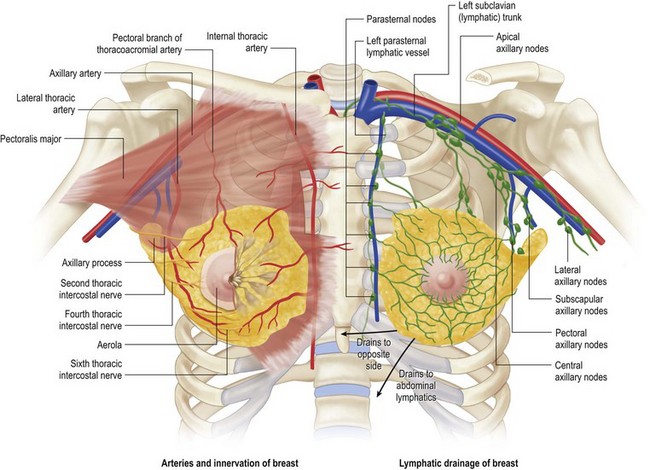

The blood supply is from the axillary artery via its thoracoacromial, lateral thoracic and subscapular arteries, and from the subclavian artery via the internal thoracic artery. The internal thoracic artery supplies the three large anterior perforating branches through the second, third and fourth intercostal spaces. The veins form a rich subareolar plexus and drain to the intercostals and axillary veins and to the internal thoracic veins (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3 Left, arteries and innvervation of breast. Right, lymphatic drainage of breast.

From Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM, et al. Gray’s atlas of anatomy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

The lymphatic drainage of the breast is of great importance in the spread of malignant disease. Several lymphatic plexi issue from the parenchymal portion of the breast and the subareolar region which drain to the regional lymph nodes, the majority of which lie within the axilla. Most of the lymph from each breast passes into the ipsilateral axillary nodes along a chain which begins at the anterior axillary nodes and continue into the central axillary and apical nodal groups. Further drainage occurs into the subscapular and interpectoral node groups. A small amount of lymph drains across to the opposite breast and also downward into the rectus sheath. Some of the medial part of the breast is drained by lymphatics, which accompany the perforating internal thoracic vessels and drain into the internal thoracic groups of nodes in the thorax and into the mediastinal nodes (Fig. 1.3).3

The innervation of the breast is principally by somatic sensory nerves and autonomic nerves accompanying the blood vessels. In general, the areola and nipples are richly supplied by somatic sensory nerves while the breast parenchyma is mostly supplied by autonomic nerves, which appear to be solely sympathetic. No parasympathetic activity has been demonstrated in the breast. Detailed histological examination has failed to demonstrate any direct neural end terminal connections with breast ductal cells or myoepithelial cells, suggesting that the principal control mechanisms of secretion and milk ejections have a humoral rather than nervous mechanism. (Although personal experience would intuitively be in conflict with this statement. EH-F) It appears that the areolar epidermis is relatively poorly innervated whereas the nipple and lactiferous ducts are richly innervated. The somatic sensory nerve supply is via the supraclavicular nerves (C3, C4) superiorly and laterally from the lateral branches of the thoracic intercostal nerves. The medial aspects of the breast receive supply from the anterior branches of the thoracic intercostal nerves which penetrate the pectoralis major to reach the breast skin. The major supply of the upper outer quadrant of the breast is via the intercostobrachial nerve (C8, T1), which gives a large branch to the breast as it traverses the axilla (Fig. 1.3).

1 Harcourt DM, Rumsey NJ, Ambler NR, et al. The psychological effect of mastectomy with or without breast reconstruction: a prospective, multicenter study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1060.

2 Brandberg Y, Malm M, Blomqvist L. A prospective and randomized study, ‘SVEA,’ comparing effects of three methods for delayed breast reconstruction on quality of life, patient-defined problem areas of life, and cosmetic result. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:66.

3 Breuing KH, Warren SM. Immediate bilateral breast reconstruction with implants and inferolateral AlloDerm slings. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(3):232-239. PMID: 16106158

4 Salzberg CA. Nonexpansive immediate breast reconstruction using human acellular tissue matrix graft (AlloDerm). Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57(1):1-5.

5 Garramone CE, Lam B. Use of AlloDerm in primary nipple reconstruction to improve long-term nipple projection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(6):1663-1668.

6 Loughry CW, Shelffer DB, Price TE, et al. Breast volume measurments in 598 women using biostereometric analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;22:380-385.

7 Westreich M. Anthropomorphic breast measurements: protocol and results in 50 women with aesthtically perfect breasts and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:468-479.

8 Suami H, Pan WR, Mann GB, et al. The lymphatic anatomy of the breast and its implications for sentinel lymph node biopsy: a human cadaver study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:863-871.

Bostwick J. Plastic and reconstructive breast surgery. St. Louis MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2000.

Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM, et al. Gray’s atlas of anatomy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

Mansel RE, Webster DJT, Sweetland HM. Benign disorders and diseases of the breast, 3rd ed. New York: Saunders; 2009.

Moses KP, Banks JC, Nava PB, et al. Atlas of clinical gross anatomy. St. Louis: Mosby; 2005.

Standring S, et al. Grays anatomy, 40th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.