Hip Arthroscopy

Jonathan E. Fow

Etiology

Arthroscopy of the hip has been performed for many years, but has become more mainstream over the last few years. Initially, it was used as a minimally invasive method of removing loose bodies. As we have learned more about variations in hip morphology, both congenital and acquired, the useful applications of hip arthroscopy have grown. Overall, hip arthroscopy can improve pain and function in 68% to 96% of surgical patients1 (Fig. 20-1).

Anatomy

Femoral acetabular impingement (FAI) is a cause of hip pain and debility. An anomalous, aspherical femoral head or anterosuperior “bump” on the femoral head and neck are features of controlled action motion (CAM) impingement (Fig. 20-2). An anterosuperior acetabular lip or retroverted acetabulum causes pincer impingement (Fig. 20-3). There is often a mixed morphology involving attributes of both CAM and pincer impingement. Femoral osteoplasty to reshape the femoral head and neck can treat CAM impingement, whereas acetabular osteoplasty can reshape the acetabular rim to improve pincer impingement.2 Both osteoplasty procedures result in improved range of motion (ROM) and function. Hip arthroscopy can address labral tears by both débridement and repair. Surgeons may perform microfracture or abrasion chondroplasty on the acetabulum also to débride cartilage lesions, and extraarticular pathology, such as gluteus medius tears, chronic iliotibial (IT) band snapping syndrome, and snapping psoas syndrome, can also be addressed endoscopically.

The complex mechanical interrelationships of the lumbar spine, hip, and lower extremity can functionally cause FAI despite near normal architecture. There can be functional impingement caused by hyperlordosis or the type of stress or activity imposed on the joint. In addition, often there exists multiple sources of pain such as degenerated discs, sacroiliac disorders, hip bursitis and IT band syndrome, hip flexor strains, and hernias. Diagnosis of FAI, loose bodies, and other causes of intraarticular or extraarticular hip pain must be confirmed while other possible sources of pain are ruled out. At the very least, patients should be aware of the risk that hip pain can be, and often is, multifactorial. Arthroscopy of the hip may only be able to address a percentage of the pain they experience.

Indications/Considerations

Patients who are seen in the office with hip pain are initially examined, their history reviewed, and radiographs taken. History of the patient’s hip pain may include chronic psoas strains, lumbar spine, and sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Transitioning to a higher or different level of activity (e.g., high school to college track) may precipitate hip pathology, as well as previous involvement and previous injuries in sports. FAI can also become symptomatic with changes in equipment, which affect body position such as shoes and bicycles.

Hip pathology is often described by a patient as groin or gluteal pain. Because hip pain can also radiate to the thigh and knee, patients may have had inappropriate knee arthroscopy.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION: Examining the lumbar spine, hip, and knee and observing posture and gait are very important in evaluating a patient with hip pain. Consider pursuing evaluation in functional positions, especially during sporting activities (e.g., running, pushing, jumping, skating, lunging). Observe the relationship of the pelvis to the lower extremities, then examine the extremities. Examine the patient walking, standing, supine, lateral, and prone.

Standing:

Gait: Observe stride length, foot progression angle, pelvis rotation, stance phase, foot drop, clicking, popping, antalgic gait, Trendelenburg gait, pelvic wink (external rotation >40), short leg limp (IT band pathology, true/false leg length discrepancy).

Patient recreation of click: Psoas or IT band.

Alignment: Note shoulder height, scoliosis, pelvic tilt; grossly measure anterosuperior iliac spine (ASIS) to medial malleolus; note spinal alignment posterior and lateral (flat lumbar spine) hyperlordotic; and consider that which would functionally affect pelvic and acetabular orientation (e.g., weak abdominal musculature, gluteus, lumbar spine, tight hamstrings). Observe single-leg stance for pelvic balance.

Sitting:

Leg length, rotation, neurologic (motor: abduction: superior gluteal nerve L4 to S1; adduction: obturator nerve L2 to 4; knee extension: L2 to 4; knee flexion: L4 to S3 sciatic nerve; great toe extension: L5; extensor hallucis longus, plantar flexion: L4 to S1; sensory: dermatomal sensation).

Supine:

ROM: External rotation, internal rotation in hip neutral and 90° of hip flexion, popliteal angle, supine abduction, frog leg abduction (knee height), adduction.

Palpate: Inguinal region, pubis, ASIS, anteroinferior iliac spine (AIIS), Stinchfield test (straight leg raise versus resistance causing pain indicates iliopsoas and/or intraarticular pathology), inferior to AIIS (labrum, anterior capsule, rectus reflected). Note: Nondisplaced or stress fracture will also hurt with straight leg raise, heel strike, and log roll.

Provocative: FADIR (flexion, adduction, internal rotation) indicates FAI and labral pathology, FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation) or Patrick test for groin, iliopsoas, lateral FAI, lateral-FAI flexion to extension in abduction (abduction), posterior labrum, and sacroiliac pathology); Thomas test: click may indicate labral tear and tightness represents iliopsoas contracture; McCarthy: full ROM from extension to flexion with external/internal rotation; Scour test: full flex and palpate superior acetabular rim for irregularity.

Lateral:

Palpate ischial tuberosity, greater trochanter, tensor fascia lata, IT band, piriformis, gluteus, sacrum, coccyx, sciatic nerve.

Ober (knee flexion and extension), test strength gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, Ely test in lateral tight quadriceps mechanism.

Prone:

Palpate sacroiliac joint, ischial tuberosity, spine, musculature. Ely test: rectus/quadriceps contracture.

Others

ROM is examined with the hip in flexion and extension. The hip is fully passively ranged and observed for pain with FADIR and FABER. Popliteal angle is evaluated to check for hamstring tightness. A loss of the arc of motion of the hip, especially internal rotation, is suspicious for significant FAI or arthritis. A low lumbar spine examination can help rule out or reveal concurrent lumbar spine pathology. Strength of abductors, adductors, hip flexors, and extensors, as well as knee and ankle muscles, can be very revealing about the functional contributions of deficits and imbalance that contribute to hip pain. Even a foot drop can contribute to overuse of hip flexors and subsequent hip pain.

Imaging

Radiographs include AP pelvis, cross-table, and frog lateral hip views. Simple radiographs can demonstrate dysplasia (decreased center-edge angle), acetabular retroversion (crossover sign), CAM lesions (increased alpha angle), loose bodies, and radiographic signs of arthritis (joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts) (Fig. 20-4). Newer studies suggest that joint space narrowing with less than 3 mm of space remaining, inferior osteophytes, and a center-edge angle of less than 20° (measure of dysplasia/shallow acetabulum) are reasons to not perform a hip arthroscopy but rather prepare the patient for a hip replacement when symptoms warrant the procedure despite conservative treatment.3 Other considerations are lumbar spine and sacroiliac pathology.

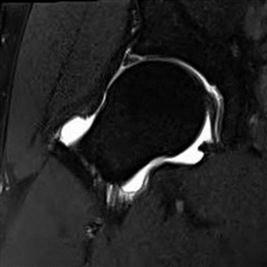

If examination and radiographs support the diagnosis of a hip problem, an MRI can be performed to observe for labral pathology, chondral injury, and loose bodies (Fig. 20-5). An arthrogram at the time of the MRI improves the accuracy of the examination, and allows injection of a local anesthetic and cortisone type of medication into the joint and observation for pain relief. If pain relief occurs, then intraarticular causes of hip pain are suggested. More specifically, response to the injection implies chondral damage.4 Depending on the cause, a computed tomographic scan with 3-D reconstructions may help better analyze the pincer impingement lesion and how much “rim trimming” may need to be performed to correct that pathology (Fig. 20-3).

Hip arthroscopy is an excellent, minimally invasive method of addressing femoral acetabular pathology previously only addressed with open hip disarticulation.

Surgical Procedure

Hip arthroscopy can be performed from two surgical positions: supine and lateral. Arthroscopic portals are identical in both positions, and the choice is really based on surgeon training and preference.

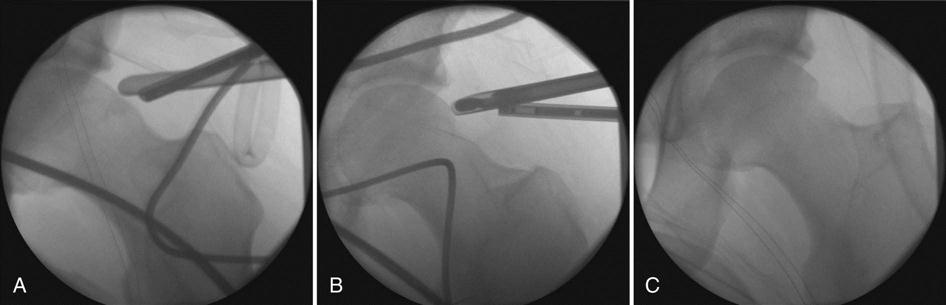

Supine hip arthroscopy can be performed with easier operating room setup. However, the posterior lateral portal is difficult to establish, and the entire procedure can be more difficult in an obese to large patient (Fig. 20-1).

Lateral hip arthroscopy requires a more complex room setup with a specialized table attachment to apply traction and position the leg. It does provide excellent access to the hip joint anterior and posterior, even in large patients.

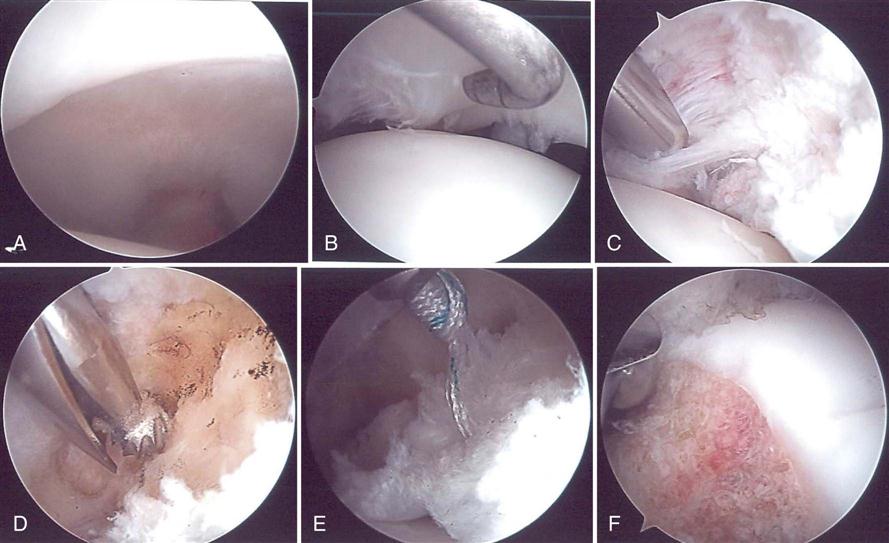

Once the patient is positioned, the anterolateral portal is established first. Various arthroscopic portals penetrate the tensor fascia lata, gluteus medius, and sartorius and rectus femoris. After careful placement with fluoroscopic guidance, the anterior portal is established next, with care taken to avoid injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. The capsule is opened between the portals and then split in a “T” or “H” shape to gain access to the femoral CAM lesion. Most surgeons start in the central compartment to look for loose bodies, cartilage injuries, ligamentous injuries, and notch osteophytes (Fig. 20-6). Cartilage injuries are often adjacent to labral injuries. In the peripheral compartment, the labrum, acetabular rim, and anterosuperior femoral neck are evaluated. Labral tears can be débrided or repaired with suture anchors. At the same time, a “rim-trimming” or acetabular osteoplasty can be performed where the pincer impingement is removed and the acetabular retroversion is improved. Care is taken via preoperative planning not to remove so much acetabulum as to destabilize the hip by respecting the CEA. The femoral CAM lesion can also be removed via a femoral osteoplasty (Figs. 20-7 and 20-8). Multiple portals can be used to access the central and peripheral compartments. A posterolateral portal, accessory anterolateral portal, and the mid anterolateral portal can be used to assist with the femoral osteoplasty, rim trimming, or anchor placement. The anterior portals may put branches of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve at risk; thus the portals are carefully closed with absorbable and/or nonabsorbable suture. A bulky dressing and an abduction pillow are placed. The surgery can be performed outpatient in a surgery center or a hospital. The surgical time can be quite prolonged, and an overnight stay may be considered.

The protocol for postoperative management varies based on whether microfracture or labral repairs are performed. Indomethacin is given for 2 weeks to help prevent postoperative heterotopic ossification (HO).5 Extra effort is taken to lavage the joint and soft tissues after the femoral osteoplasty, but HO is still possible and one reason for reoperation. After surgery, the patient can be sent home with arrangements for a continuous passive motion machine, crutches or walker, and a hip cryo-sleeve.

Outcomes

Depending on the condition of the acetabular cartilage and possibly the labrum, patients can do quite well. Long-term outcomes can be very satisfying, delaying or preventing the need for hip replacement. A more severe or involved acetabular cartilage damage predicts a poorer outcome and earlier need for arthroplasty.

Surgical challenges are related to the acetabular cartilage damage, severity of the CAM impingement, and labral takedown and rim-trimming for pincer impingement. Recent studies suggest superior outcomes in labral repair (Harris Hip Score 89.7% vs. 66.7% good to excellent results). Although it may make sense to recreate the labral “gasket,” a large definitive study needs to be published.6 The labrum contributes to hip stability. Hip stability is not reduced until 2 cm has been removed.7

Although hip arthroscopy is safer and has a faster rehabilitation rate than an open procedure, complications can still occur. Various studies quote an up to 18% complication rate.8 They include neuropraxia of the sciatic, femoral, or lateral femoral cutaneous nerve; HO (1.6%); portal wound bleeding; and instrument breakage. Other case reports describe complications that include femoral neck fracture,9 dislocation,10 trochanteric bursitis, abdominal compartment syndrome,11 intrathoracic extravasation of fluid,12 avascular necrosis,13 and penetration of the acetabulum by anchors.14 A common reason for reoperation is underresection of the CAM lesion. Postoperative radiographs can show the improvement in CAM lesions and elimination of the crossover sign. The need for a conversion to a total hip arthroscopy is as high as 26%.

Neuropraxias can be related to portal placement or distraction. Symptoms are usually short-lived and resolve completely. HO can occur, and indomethacin is given after surgery to help prevent its formation. Patients can develop painful stiffness several weeks after surgery despite early good ROM. Therapy is essential to try to restore and maintain ROM at this point. If HO forms and is symptomatic, it can be resected. The patient is given indomethacin and radiation to help prevent recurrence at the time of the resection of HO. After labral repair, care must be taken to avoid impingement, which may stress the repair before healing (≥6 weeks). Furthermore, after microfracture in the hip, it is recommended to limit weight bearing, and many surgeons advocate the use of a postoperative continuous passive motion for reasons similar to its use after microfracture in the knee.

Possible Complications

In addition to the complications previously listed, there are a few other potential rehabilitation concerns. Pain control is important so that the therapist can properly mobilize the hip; this seems to be a focus over the first several weeks. Maintaining weight-bearing status is also important for protecting the healing labrum and microfracture bed. Sudden stiffness or mechanical signs may forebode reinjury of the labrum, worsening cartilage injury (or frank rapid-onset osteoarthritis), avascular necrosis, or developing HO and would necessitate communication with the surgeon.

Various types of procedures can be performed to correct hip pathology through hip arthroscopy surgery. Cartilage and lesions can be débrided. For example, labral tears can be débrided or repaired. Osteoplasty procedures can be done to improve ROM and function, including chondroplasty to the acetabulum for microfractures and abrasions. Also, extraarticular pathology, such as gluteus medius tears, chronic IT band snapping syndrome, and snapping psoas syndrome, can also be addressed. The rehabilitation progression will vary depending on the hip pathology and procedure.

Summary

This chapter equips the rehabilitation professional with an understanding of the various procedures performed using hip arthroscopy. Also, a description of a hip arthroscopy is provided so that the reader can appreciate the different tissues that are compromised, altered, or repaired during this surgery.