Chapter 172 Herpes Simplex

Diagnostic Summary

Diagnostic Summary

• Acute or recurrent viral infection of the skin or mucous membranes characterized by the appearance of grouped vesicles on an erythematous base frequently occurring about the mouth (herpes gingivostomatitis), lips (herpes labialis), genitals (herpes genitalis), and conjunctiva and cornea (herpes keratoconjunctivitis)

• Incubation period of 2 to 12 days, average 6 to 7

• Positive culture, vesicle scraping stained with Giemsa stain, or serologic test (type-specific glycoprotein testing for both herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2)

• Regional lymph nodes sometimes tender and swollen

• Outbreak may follow minor infections, trauma, hormonal fluctuations, stress (emotional, dietary, and environmental), and sun exposure

• Viral shedding, leading to possible transmission, during primary infection, recurrences, and (asymptomatically) between recurrences

General Considerations

General Considerations

More than 70 viruses compose the Herpesviradae family. Of these, four are important in human disease: herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus. Serologic methods have distinguished two types of HSV, which have been designated HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 is frequently acquired in early childhood, with evidence of serologic infection approaching 90% in adults. More than one-third of the world’s population has recurrent HSV. Although 80% of seropositive individuals do not have clinically apparent recurrences, they still shed virus asymptomatically. Current estimates indicate that 20% to 40% of people in the United States have recurrent HSV infections.1 Previously, HSV-1 was primarily isolated from extragenital sites, while genital infections were caused primarily by HSV-2. By the year 2000, however, HSV-1 had replaced HSV-2 as the primary cause of genital lesions, likely due to orogenital contact.2 A retrospective review of genital HSV isolates collected in a university student health service showed that HSV-1 accounted for 78% of all genital isolates in this population by 2001, compared with 31% of isolates in 1993.3 Individuals who are exposed to HSV and have asymptomatic primary infections may experience an initial clinical episode of genital herpes months to years after becoming infected.

Therapeutic Considerations

Therapeutic Considerations

Enhancement of the host’s immunologic status is a key goal in the control of herpes infection. In addition to general immune support (for a complete discussion, see Chapter 56) one of the key natural measures to strengthen cell-mediated immunity is the use of polypeptide-rich bovine thymus extracts. These have been shown to be effective in preventing both the number and severity of recurrent infections in immune-suppressed individuals.4 Thymus extract appears to increase the lymphoproliferative response to HSV, natural killer cell activity, and interferon production, thus preventing viral activation by potentiating these cell-mediated immune responses.

Nutritional Supplements

Zinc

Oral supplementation with zinc (50 mg/day) has been shown to be effective in clinical studies.5 Although zinc is an effective inhibitor of HSV replication in vitro, its effect in vivo is probably related to its role in enhancing cell-mediated immunity. The topical application of 0.01% to 0.025% zinc sulfate solutions has also been shown to be effective in both ameliorating symptoms and inhibiting recurrences of HSV infection.6

Vitamin C

Both the oral consumption and topical application of vitamin C increase the rate of healing of herpetic ulcers. In a randomized double-blind study, an ascorbic acid–containing pharmaceutical formulation (Ascoxal) applied with a soaked cotton wool pad three times daily for 2 minutes resulted in patients reporting fewer days with scabs and fewer cases of worsening of symptoms. Cultures yielded herpes complex viruses significantly less frequently in the treatment group.7 In another study, 20 patients with herpes labialis were treated with a complex of 600 mg water-soluble bioflavonoids and 600 mg vitamin C given orally in equal increments three times daily. Twenty episodes of herpes labialis were treated with a complex of 1000 mg water-soluble bioflavonoids and 1000 mg of vitamin C in equal increments five times daily. Ten episodes were treated with a lactose preparation. This approach was maintained for 3 days after the recognition of symptoms. The water-soluble bioflavonoid–vitamin C complex was shown to reduce vesiculation and to prevent disruption of the vesicular membrane. The therapy was most beneficial when it was initiated at the beginning of the disease. Those treated with the 1000-mg regimen saw their blisters heal in 4.4 days, compared with 10 days for the placebo group. Optimal remission of symptoms was observed in 4.2 +/- 1.7 days with the 600-mg dosage of the water-soluble bioflavonoid/ascorbic acid complex.8 Vitamin C has also been employed intravenously with benefit in the treatment of patients with HSV infection, including AIDS patients.9

Lysine and Arginine

A lysine-rich/arginine-poor diet has become a popular treatment for HSV infections. This approach came from research showing that lysine has antiviral activity in vitro owing to its antagonism of arginine metabolism.10 HSV replication requires the synthesis of arginine-rich proteins, and arginine itself is suggested to be an operon coordinate inducer.11 A preponderance of lysine over arginine is believed to act as either an allosteric enzyme inhibitor or an operon coordinate repressor.

Double-blind studies on the effectiveness of lysine supplementation with uncontrolled avoidance of arginine-rich foods have shown inconsistent results.11–14 These outcomes may be due to the relatively low levels of lysine used (1200 mg/day) and the severity of the cases in some of the studies (placebo and treated groups had lesions for 40% of the time in one negative study).11,12 In one study, lysine was given at a larger dosage (1 g three times daily) along with the dietary restriction of nuts, chocolate, and gelatin.13 At 6 months, lysine was rated as effective or very effective by 74% of those receiving lysine compared with only 28% of those receiving the placebo. The mean number of outbreaks was 3.1 in the lysine group compared with 4.2 in the placebo group.

Theoretically, this approach should be effective, because in vitro studies have shown that HSV replication depends on adequate levels of arginine and low levels of lysine.14 As dibasic amino acids, they compete with each other for intestinal transport, and rats fed a lysine-rich diet displayed a 60% decrease in brain arginine levels, although there was no change in serum levels.9 Because HSV is believed to reside in the ganglia during latency, lysine supplementation and arginine avoidance seem appropriate. However, this approach is not curative—it only inhibits recurrences. In some patients, withdrawal from lysine is followed by relapse within 1 to 4 weeks.14

Topical Preparations

Melissa officinalis

One of the most widely used topical preparations in the treatment and prevention of herpes outbreaks is a concentrated extract (70:1) of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm). Rather than a single antiviral chemical, Melissa contains several components that work together to prevent the virus from infecting human cells. When Melissa cream was used in patients with an initial herpes infection, results from comprehensive trials in three German hospitals and a dermatology clinic demonstrated that there was not a single recurrence.16 In other words, by using the cream, not a single patient with a first herpes outbreak developed another cold sore.

Furthermore, it was noted in these studies that the Melissa cream produced an interruption of the infection and promoted healing of the herpes blisters much faster than normal. The control group receiving other topical creams had a healing period of 10 days, while the group receiving the Melissa cream healed completely within 5 days. The Melissa cream was also studied in patients suffering from recurrent cold sores. Researchers found that if subjects used this cream regularly, they would either stop having recurrences or experience a tremendous reduction in the frequency of recurrences (an average cold sore–free period of >3.5 months).17

The Melissa cream should be applied to the lips two to four times daily during an active recurrence. It can be applied fairly thickly (1 to 2 mm). Detailed toxicology studies have demonstrated that it is extremely safe and suitable for long-term use. Extracts of other species of the Lamiaceae family have also shown in vitro efficacy against the adsorption, but not replication of HSV-1 and HSV-2, including Mentha piperita, Prunella vulgaris, Rosmarinus officialis, Salvia officinalis, and Thymus vulgaris.18

Glycyrrhiza glabra

Another popular ingredient for the topical treatment and prevention of herpes outbreaks is glycyrrhetinic acid. This triterpenoid component of Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice root) inhibits both the growth and cytopathic effects of herpes simplex as well as vaccinia, Newcastle disease, and vesicular stomatitis viruses.19 Topical glycyrrhetinic acid has been shown in clinical studies to be helpful in reducing the healing time and pain associated with cold sores and genital herpes.20–22

Resveratrol

Resveratrol (3,5,4’-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a natural component of certain foods such as grapes; it has been shown to have anti-HSV activity in vitro. Intriguing research in mice has shown that the topical application of a cream rich in resveratrol (12.5% to 25%) effectively blocked replication of the HSV virus and stopped lesion eruption if applied early and frequently.23,24 No human studies have been reported; however, subsequent in vitro studies have yielded data indicating that resveratrol suppresses HSV-induced activation of NF-kappaB within the nucleus and impairs the expression of essential immediate-early, early, and late HSV genes and the synthesis of viral DNA.25

Therapeutic Approach

Therapeutic Approach

Diet

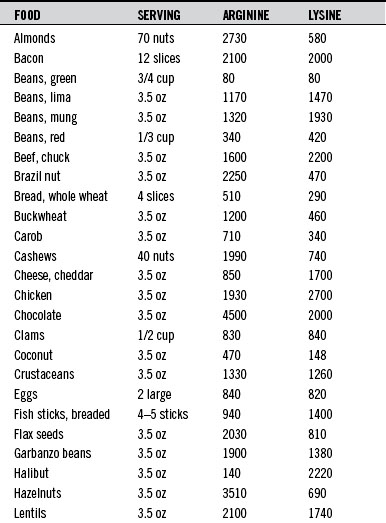

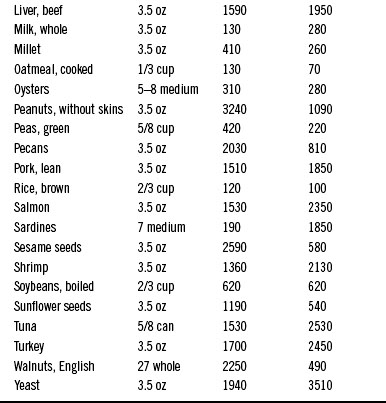

A diet that avoids major food allergens and limits arginine-rich foods while promoting lysine-rich foods is recommended (see Table 172-1). The foods with the worst arginine-to-lysine ratio are chocolate, peanuts, and almonds.

1. Malkin J.E. Epidemiology of genital herpes simplex virus infection in developed countries. Herpes. 2004;11(suppl 1):2A–23A.

2. Lafferty W.E. The changing epidemiology of HSV-1 and HSV-2 and implications for serological testing. Herpes. 2002;9:51–55.

3. Roberts C.M., Pfister J.R., Spear S.J. Increasing proportion of herpes simplex virus type 1 as a cause of genital herpes infection in college students. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:797–800.

4. Aiuti F., Sirianni M., Stella A., et al. A placebo-controlled trial of thymic hormone treatment of recurrent herpes simplex labialis infection in immunodeficient hosts. Int J Clin Pharm Ther Toxicol. 1983;21:81–86.

5. Fitzherbert J. Genital herpes and zinc. Med J Aust. 1979;1:399.

6. Brody I. Topical treatment of recurrent herpes simplex and post-herpetic erythema multiforme with low concentrations of zinc sulphate solution. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:191–213.

7. Hovi T., Hirvimies A., Stenvik M., et al. Topical treatment of recurrent mucocutaneous herpes with ascorbic acid-containing solution. Antiviral Res. 1995;27:263–270.

8. Terezhalmy Gt, Bottomley W.K., Pelleu G.B. The use of water-soluble bioflavinoid-ascorbic acid complex in the treatment of recurrent herpes labialis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;45(1):56–62.

9. Cathcart R.F. Vitamin C in the treatment of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Med Hypotheses. 1984;14:423–433.

10. Griffith R., DeLong D.C., Nelson J.D. Relation of arginine-lysine antagonism to herpes simplex growth in tissue culture. Chemotherapy. 1981;27:209–213.

11. DiGiovanna J.J., Blank H. Failure of lysine in frequently recurrent herpes simplex infection. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:48–51.

12. Griffith R., Norins A., Kagan C. A multicentered study of lysine therapy in herpes simplex infection. Dermatologica. 1978;156:257–267.

13. McCune M.A., Perry H.O., Muller S.A. Treatment of recurrent herpes simplex infections with L-lysine monohydrochlorite. Cutis. 1984;34:366–373.

14. Griffith R.S., Walsh D.E., Myrmel K.H., et al. Success of L-lysine therapy in frequently recurrent herpes simplex infection. Dermatologica. 1987;175:183–190.

15. Gaby A. Natural remedies for herpes simplex. Altern Med Rev. 2006 Jun;11(2):93–101.

16. Wolbling R.H., Leonhardt K. Local therapy of herpes simplex with dried extract from Melissa officinalis. Phytomedicine. 1994;1:25–31.

17. Koytchev R., Alken R.G., Dundarov S. Balm mint extract (Lo-701) for topical treatment of recurring herpes labialis. Phytomedicine. 1999;6:225–230.

18. Nolkemper S., Reichling J., Stintzing F.C., et al. Antiviral effect of aqueous extracts from species of the Lamiaceae family against Herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in vitro. Planta Med. 2006 Dec;72(15):1378–1382.

19. Pompei R., Pani A., Flore O., et al. Antiviral activity of glycyrrhizic acid. Experientia. 1980;36:304.

20. Partridge M., Poswillo D. Topical carbenoxolone sodium in the management of herpes simplex infection. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;22:138–145.

21. Csonka G., Tyrrell D. Treatment of herpes genitalis with carbenoxolone and cicloxolone creams: a double blind placebo controlled trial. Br J Vener Dis. 1984;60:178–181.

22. Ikeda T., Yokomizo K., Okawa M., et al. Anti-herpes virus type 1 activity of oleanane-type tripterpenoids. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005 Sep;28(9):1779–1781.

23. Docherty J.J., Smith J.S., Fu M.M., et al. Effect of topically applied resveratrol on cutaneous herpes simplex virus infections in hairless mice. Antiviral Res. 2004;61:19–26.

24. Faith S.A., Sweet T.J., Bailey E., et al. Resveratrol suppresses nuclear factor-kappa B in herpes simplex virus infected cells. Antiviral Res.. 2006 Dec;72(3):242–251.

25. Fink M., Fink J. Treatment of Herpes simplex by alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E). Br Dent J. 1980;148:246.

26. Faith SA, Sweet TJ, Bailey E, et al. Resveratrol suppresses nuclear factor-kappa B in herpes simplex virus infected cells. Antiviral Res. 72:242-251.