15 Hernia

Definitions

Specific sites of abdominal hernias

Inguinal hernia

A pantaloon hernia is a combination of the two.

Indirect hernias are usually derived from a remnant of the processus vaginalis which does not close. It is therefore more common in infancy. Sixty per cent occur on the right side and they are twenty times more common in men than women. Direct hernias are acquired lesions and usually a condition of later life. The differences between an indirect and direct inguinal hernia are shown in Table 15.1.

Table 15.1 Differences between indirect and direct inguinal hernia

| Indirect | Direct | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient’s age | Any age but usually young | Older |

| Cause | May be congenital | Acquired |

| Bilateral | 20% | 50% |

| Protrusion on coughing | Oblique | Straight |

| Appearance on standing | Does not reach full size immediately | Reaches full size immediately |

| Reduction on lying down | May not reduce immediately | Reduces immediately |

| Descent into scrotum | Common | Rare |

| Occlusion of internal ring | Controls | Does not control |

| Neck of sac | Narrow | Wide |

| Strangulation | Common | Rare |

| Relation to inferior epigastric vessels | Lateral | Medial |

Femoral hernia

The differential diagnosis of a femoral hernia is shown in Table 15.2. Femoral hernias account for 7% of all hernias and are four times more common in women than men (although inguinal hernias are still more common in women than femoral). They are most common in late middle age and are rare in children. Bilateral hernias occur in 20%. The femoral canal is bounded by the inguinal ligament (anteriorly), the lacunar part of the inguinal ligament (medially) and the pectineal part of the inguinal ligament (posteriorly). This narrow femoral ring produces considerable risk of incarceration of any hernia. The narrow canal makes femoral hernia the one most likely to result in a Richter’s hernia.

Table 15.2 Inguinal swellings which may resemble a femoral hernia

| Condition | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inguinal hernia |

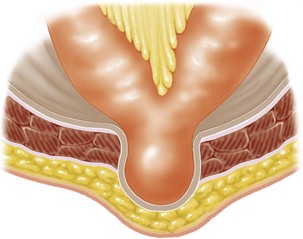

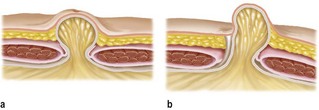

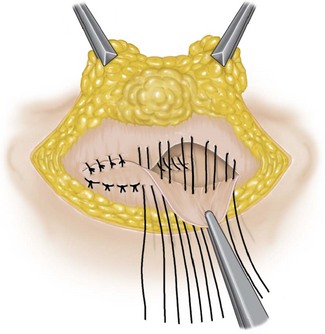

Umbilical hernia

• true umbilical hernia: a protrusion through the umbilical scar

• para-umbilical hernia: usually at the superior aspect between the umbilical vein and upper margin of the umbilical ring.

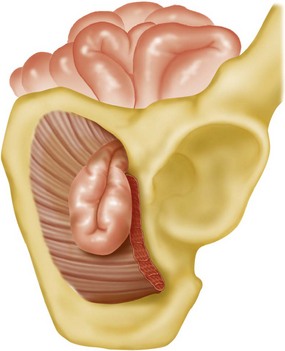

Obturator hernia

This is mostly seen in frail, elderly women (Fig. 15.4). Richter’s strangulation is common. Fifty per cent of patients complain of pain along the upper medial side of the thigh with episodes of previous obstructive-like symptoms. Signs are rare and the diagnosis is most often made at laparotomy for small bowel obstruction.