Chapter 37 Herb–nutrient–drug interactions

With contribution from Dr Antigone Kouris-Blazos

Introduction

In the United States, approximately 1 in 4 persons prescribed pharmaceutical medications also consume a dietary supplement.1, 2 Dietary supplements that include herbs, vitamin and/or mineral preparations, and other dietary supplements such as glucosamine and fish oils, may augment or antagonise the actions of prescription and non-prescription drugs. This is because supplements have demonstrated pharmacologic actions that may then go on to produce therapeutic outcomes.3 Moreover, supplements that do not have a documented pharmacologic action can also significantly affect the absorption, metabolism, and disposition of other pharmaceutical products. Health professionals usually question the nutritional adequacy and safety of a patient’s diet, however the nutritional impact of medications is often overlooked. Pharmaceuticals have both beneficial and adverse effects, although there is a strong focus on the benefits. Furthermore, drug–drug interactions are generally integral to decision-making yet the impact of drug–food and drug–nutrient interactions are rarely acknowledged or, mostly, deemed clinically insignificant.

Some vitamin–mineral–herbal supplements require separation from medications by about 2–4 hours to avoid potential problems with absorption or interactions. See the medications in Table 37.1 for more specific advice in relation to this rule.

Table 37.1 Common herbs and nutrients and their interactions with medications

| Drugs | Interactions | |

|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system and sedating medication | ||

| Herb | Effect | |

| St John’s wort | ||

(a) All patients on warfarin should be monitored closely with the introduction of any complementary medicine such as garlic, fish oils, ginseng and ginkgo.

(b) Given the serious consequences associated with small changes in the coagulation status, patients on warfarin should be carefully monitored when: 1) initiating or stopping any nutritional or herbal supplement 2) commencing new bottles of the same product in case of product variation.

(c) Monitor serum digoxin levels in patients taking St John’s wort and ginseng.

(d) Separate psyllium by several hours to allow the absorption of drugs to occur more effectively.

Types of herb–drug interactions

There are 2 types of interactions that occur between natural products and pharmaceuticals.

The evidence documenting dietary supplement–drug interactions varies extensively. There is at present no process for the systematic evaluation of dietary/nutritional supplement products for possible interactions with prescription medications. As a result of this deficit, there is an incomplete knowledge of the interactions that may occur. The information is largely researched from many different sources including animal studies, human case reports, case series, historical contraindications, and the extrapolation from basic pharmacology data, or from clinical trials. Many of the recommendations associated with herb–drug interactions are based on speculation rather than research.4 According to a recent study, overall the risk of actual harm from a herb–drug interaction is low.5 According to the authors the 5 most common natural products with a potential to affect medications include garlic, St John’s wort, ginkgo, valerian and kava. These herbal medicines accounted for 68% of the potential clinically signifi cant interactions in the survey. The 4 most common prescription medicines affected by supplements are antithrombotics, such as warfarin, antidepressants, sedatives and anti-diabetic agents.

Types of nutrient–drug interactions

Pharmaceuticals can affect and be affected by nutrition.

As a general rule, it is advisable to separate vitamin and/or mineral supplements from medications by about 2–4 hours to reduce any potential interactions. However, where the drug affects metabolism or excretion of a nutrient such a simple rule may not apply.

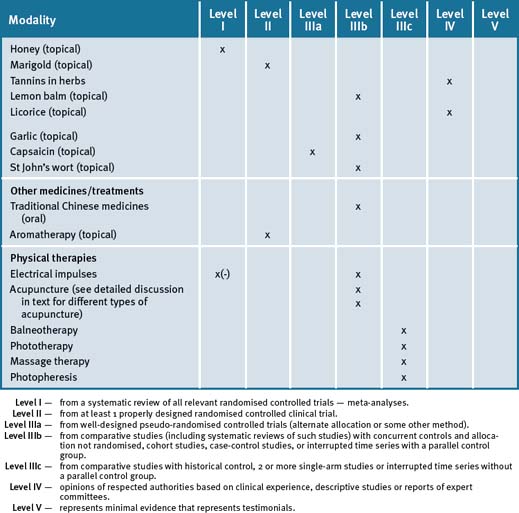

Figure 37.1 lists the top 12 nutrient-depleting drugs (see also Appendix 2).6, 7

Figure 37.1 Top nutrient-depleting drugs∗

∗Consider recommending foods high in these nutrients; if blood tests suggest deficiency then a supplement may be needed (see Chapter 2, Nutritional assessment and therapies).

Nutrient absorption

Pharmaceuticals can affect the absorption of nutrients via:

Nutrient metabolism

Altered cellular metabolism can result from the pharmaceutical:

Patient populations and specific pharmaceuticals

Antacid medication

Antacids neutralise stomach acid and their high levels of calcium can interfere with the absorption of Fe, Zn, Cr, Cu, vitamins A, B1, B12, folate, D, E, K. They can also impair appetite and alter taste. Aluminium in some antacids (e.g. Mylanta®) can bind dietary phosphates and this can further lead to calcium depletion and cause osteomalacia. Ca/Mg citrate, vitamin C supplements, citrus juices and milk can increase aluminium absorption so should be separated from drug consumption by at least 2 hours. Fe/Zn/fibre supplements and foods high in oxalates (e.g. tea, wheat germ) and phytates (e.g. bran, oats) can reduce absorption of antacids. Long-term use of antacids can increase serum magnesium levels. Elderly patients should not take antacids at meal times or with other dietary supplements. (See Appendix 2 for references.)

Psychiatric medications

St John’s wort is today most widely known as a herbal treatment for depression. St John’s wort has been documented to be one of the most common natural products with a potential for interaction.5, 8

St John’s wort pharmacodynamic action may have an effect on serotonin levels even though this is not probably its inherent mechanism of action in the treatment of depression. It has been associated with serotonin syndrome due to raised serotonin levels in patients also receiving a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).9 It has been reported that St John’s wort should gradually be reduced when an SSRI is initiated.10

St John’s wort pharmacokinetic interactions have been extensively demonstrated to decrease serum levels of psychiatric medications metabolised by the CYP450 enzyme system.11, 12, 13 Also, although changes in serum levels of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants with the use of St John’s wort have been reported, these changes may not result in a significant clinical effect.12–15

Oral contraceptive pill (OCP)

As St John’s wort can induce the enzyme cytochrome P450, it can potentially affect the levels of any drugs that are metabolised by this pathway, such as anti-epileptics and the oral contraceptives. There have been reported cases of break-through bleeding in women taking the OCP and St John’s wort increasing the risk of pregnancy.16 However, a recent study has reported that a low dose of St John’s wort extract Ze117 which was reported to have a low hyperforin content, did not interact with the pharmacokinetics of the hormonal components of the low-dose oral contraceptive.17

Anticoagulant medication

Warfarin

There have been documented case reports on interactions between the anticoagulant warfarin and St John’s wort, Ginkgo biloba (gingko), garlic, and ginseng.18, 19

Studies have demonstrated that St John’s wort increases the metabolism of warfarin, leading to significantly reduced serum levels of the drug.20–23 However, the clinical response to the combination has not been quantified.

Care must be taken with patients on warfarin starting any complementary medicine. INR should be checked within 2 weeks of starting the complementary medicine.

Ginkgo biloba extracts from the ginkgo leaves contains flavonoid glycosides and terpenoids (ginkgolides, bilobalides). It has many alleged nootropic properties, and is mainly used as a memory and concentration enhancer and as an anti-vertigo agent.24 Animal and in vitro data suggest that Ginkgo biloba extracts may modulate CYP3A4 enzyme system activity.25 Ginkgo biloba does not interact with warfarin or aspirin but has been demonstrated to have anti-platelet activity.26, 27 A randomised cross-over study to assess the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin with ginkgo and ginger demonstrated that at recommended dosage these herbs do not significantly affect clotting status of warfarin in healthy subjects.26 However, in combination with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, ginkgo has been reported to cause severe bleeding, including intracranial bleeding.28–30

Animal studies, and some early investigational studies in humans, have suggested possible cardiovascular benefits of garlic. Garlic has intrinsic anti-platelet activity.31 However, a recent clinical trial has demonstrated that garlic is safe and poses no serious haemorrhagic risk for monitored patients prescribed warfarin.32 Further, a recent review of the literature concluded that there is no evidence that supports the concern of perioperative bleeding in users of garlic.33 Nevertheless, care must be taken when prescribed with warfarin.

A low-level of evidence clinical study found no effect of Asian ginseng (Panax ginseng) in combination with warfarin.30 American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), a separate plant, decreases warfarin serum levels in humans, resulting in less anticoagulation.30 Further, another study has reported that American ginseng significantly reduced peak plasma warfarin level and warfarin INR.34 Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus) has not been studied; however, it contains a constituent that inhibits platelet aggregation. A recent review concludes that there is no evidence linking the use of ginseng to perioperative bleeding.33 Specifically, patients receiving American ginseng should be monitored when changing products or even bottles of the same product.35, 36

Putative antioxidants such as vitamin E and essential fatty acids from fish oil are often cited in scientific reviews of nutritional supplement–drug interactions.37, 38 In a small clinical study of 16 patients, fish oils (3–6g/day) were reported to not affect the coagulation status in patients who were receiving warfarin.39 Nevertheless, caution is needed due to anti-platelet effects of fish oils. A recent expert opinion on fish oils has surmised that the benefits of triglyceride lowering with omega-3 fatty acids more than outweighs any theoretical risks for increased bleeding.40

In vitro studies demonstrate enhancement of the anti-platelet effect of aspirin by vitamin E and therefore it has been suggested that it may have an effect on bleeding time.41 However, clinical trials with and without warfarin and vitamin E have demonstrated no clear increased risk of bleeding even though high doses of vitamin E were used and could have antagonised vitamin K levels.42–44

Cranberry juice contains polyphenolic and phytochemical compounds with possible benefits to the cardiovascular system, immune system and as an anti-cancer agent.45–49 In 2004 the Committee on Safety of Medicines — the UK agency dealing with drug safety — advised patients taking warfarin not to drink cranberry juice because adverse effects such as increased incidence of bruising were reported from case reports, possibly resulting from the presence of salicylic acid native to polyphenol-rich plants such as the cranberry. It may also increase INR by inhibiting the CYP450 enzyme-reducing metabolism of warfarin. However, recent reviews of case reports and pilot studies have failed to confirm this effect, collectively indicating no significant interaction between daily consumption of 250 mL of cranberry juice and warfarin.50, 51, 52 A controlled study demonstrated no effect on coagulation.50

Given that warfarin has a narrow therapeutic index and the serious consequences associated with small changes, the anticoagulation status in patients taking dietary supplements containing blood thinning herbs or vitamins (see Table 37.2 at the end of this chapter) should be carefully monitored whenever they initiate or stop taking any nutritional supplement. Moreover, patients on warfarin should also be monitored when they commence new bottles of the same product in case of product variations, and until the effect in the individual patient is known.

| Potential blood thinning foods and herbs which may interact with blood thinning medication and theoretically should be avoided at least 1–2 weeks prior to and 1 week after surgery | |

(Source: EBSCO Publishing. Online. Available: http://healthlibrary.epnet.com/GetContent.aspx?token=1edc3d6e-4fec-4b20-baca-795e48830daa [accessed 4 Sept 2010]; Braun L, Cohen M. Herbs and Natural Supplements: an evidence-based guide (2nd edn). Elsevier, Sydney, 2007; Health Notes Online. Available: http://www.pccnaturalmarkets.com/health/2411003/ [accessed 4 Sept 2010])

Aspirin

Aspirin can reduce the absorption of B12, folate, vitamin C, Fe, Zn, Ca and increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and anaemia with chronic use, primarily at high doses. Aspirin can also reduce appetite. A high intake of omega-3 EPA/DHA (>3000mg/day) from fish oil or flaxseed oil (>30g/day) or evening primrose oil (>1g/d) or vitamin E (>100IU) with aspirin may increase risk of haemorrhagic stroke. Other blood thinning herbs and/or foods that have the potential to increase the blood thinning effects of aspirin (and warfarin or clopidogrel) if taken at high supplemental doses include: Aloe vera, carnitine, chamomile, chondroitin, cinnamon, CoQ10, cranberry, devil’s claw, dong quai, feverfew, garlic, ginger, gingko, ginseng, glucosamine, goji, grape seed extract, green tea, krill oil, policosanol, saw palmetto, turmeric and willow bark. (See Appendix 2 for references.)

For a list of herbs and foods that may interact with anticoagulant medication, see Table 37.2.

Cardiovascular medication

Of all the supplements used by patients who have cardiac disease, St John’s wort (used to treat mood disorders) is associated with the most interactions. It can decrease serum concentrations of drugs including most calcium channel blockers and statins.53, 54, 55 Blood pressure and lipid levels, respectively, should be monitored closely if a patient is taking 1 of these drugs concomitantly with St John’s wort.

The mechanisms of St John’s wort on the pharmacokinetics of other drugs is due to induction of cytochrome P450 (CYP450) isoenzymes CYP3A4, CYP2C9, and CYP1A2, and of the transport protein P-glycoprotein, leading to decreased concentration of medications.56 In 1 study, St John’s wort was reported to have decreased digoxin blood levels by 25%. The most likely mechanism was by inducing P-glycoprotein and the clearance of digoxin.57, 58

Ginseng which is a commonly used herb5 has been reported to cause an increase in digoxin serum levels in a case report of 1 patient.59 At present digoxin levels should be monitored in patients taking Siberian ginseng or St John’s wort (or any supplement for that matter, since digoxin has a narrow therapeutic window).

Laxative medication

Psyllium commonly used as a dietary fibre is not absorbed by the small intestine. The purely mechanical action of psyllium mucilage absorbs excess water while stimulating normal bowel elimination. Although its main use has been as a laxative, it is more appropriately termed a true dietary fibre. With other related bulk-forming laxatives, these dietary supplements are often not considered to be medications by many patients. However, they can slow or diminish absorption of many pharmaceutical drugs.60

Psyllium has been reported to reduce the concentration of carbamazepine absorption and its serum levels.61 In addition, a case report has demonstrated that psyllium decreased the absorption of lithium.62

Diabetes medication

Metformin/pioglitazone/sulfonylureas can decrease absorption of vitamin B12 and folate. Magnesium supplements can increase absorption of pioglitazone and sulfonylureas these drugs can also reduce appetite and alter taste. K/Mg citrate supplements may reduce their therapeutic effect. Short-term studies have not found glucosamine supplements to have an adverse effect on blood glucose levels in diabetics. Sulfonylureas can affect thyroid function (and cause weight gain) by reducing the uptake of iodine by the thyroid. (See Appendix 2 for references.)

Currently nutrient-herb–drug interactions are not well documented in patients being treated for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). However, a number of supplements have been reported to have intrinsic effects on serum glucose. In a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) to demonstrate a hypotensive effect of hawthorn in patients with diabetes taking medication, it was reported that no herb–drug interaction was found.63

Chromium and psyllium also have been reported to have hypoglycaemic effects.64, 65, 66 Also ginseng, fenugreek and Gymnema sylvestre have demonstrated in vivo hypoglycaemic activity and in patients with diabetes this effect might be additive when combined with oral hypoglycaemics or insulin.67, 68, 69

Recently it has been reported that bitter melon (Momordica charantia) has a similar affect to rosiglitazone.70 The cumulative evidence demonstrates that bitter melon and fenugreek may be useful for the treatment of T2DM.71

The effect of these supplements may be unpredictable in T2DM, and hypoglycaemic medication may need to be altered if blood glucose changes occur.2

Thyroxine (T4)

Thyroxine does not cause nutrient deficiencies, however, its absorption is reduced by food and mineral supplements. Thyroxine should be taken on an empty stomach, ideally 1 hour before food or 2 hours after food. Meals high in fibre and/or soy should also be separated from thyroxine by several hours. Any supplements or fortified foods (e.g. Anlene milk) containing minerals, especially Ca, Fe, Zn, chromium and Se, should be taken with a gap of 4 hours from taking thyroxine. Secretion of TSH, production of T4 by the thyroid and conversion of endogenous or exogenous T4 to T3 in the thyroid, liver and other tissues requires an adequate intake of I, Fe, Se, Zn, Mg, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin A and tyrosine. Correcting deficiencies of these nutrients may have an additive effect on thyroid function that may result in a need for a reduced dose of thyroxine. This may be desirable since thyroxine therapy can have side-effects (e.g. potentiates glucose intolerance). Mild iodine deficiency has re-emerged in Australia over the last 10–15 years, with 43% of the population having inadequate iodine intakes. (See also Chapter 32, pregnancy disorders.) Good food sources of iodine include kelp/seaweed, fish and iodised salt. Iodine deficiency can be detected by way of several fasting urinary iodine tests (iodine/creatine ratio). If iodine deficiency is identified, a low dose iodine supplement (100mcg/day) approaching the RDI of 150mcg/day may be necessary with a concomitant reduction in thyroxine dose. High dose iodine supplements should be avoided as they can block thyroid hormone synthesis and create an underactive state. A T4:T3 ratio >3 may suggest selenium deficiency. However, since both I and Se deficiencies can co-exist, iodine deficiency must be corrected first to enable the thyroid to respond to selenium supplementation. Foods and/or supplements that may have an additive effect on thyroid function include low dose iodine/kelp/seaweed, Fe, tyrosine, withania and brahmi. Foods and/or supplements that may reduce thyroid function or the effects of thyroxine include high dose iodine/kelp/seaweed, isoflavones, lemon balm, bugleweed, red rice yeast extract, SAMe, carnitine, and celery seed. Goitrogenic foods include raw broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, garlic, onion, linseed, rapeseed, lima beans, soy, peanuts, swede, sweet potato, and millet; they usually reduce utilisation of iodine by the thyroid by blocking the uptake of iodine, particularly when dietary iodine intake is low, potentially reducing thyroid production. This may be a useful effect in patients with hyperthyroidism. However, if iodine intake is adequate in patients with hypothyroidism, these foods will have a minor effect on thyroid production and will probably not cause problems. (See Appendix 2 for references.)

HIV medication

Herbal medicines are widely used by HIV patients. Several herbal medicines have been shown to interact with antiretroviral drugs, which might lead to drug failure.68 Echinacea purpurea (echinacea), garlic, ginkgo, milk thistle, and St John’s wort have the potential to cause significant interactions with antiretroviral medication.

St John’s wort is the herbal supplement with the most evidence of an effect on these enzyme systems.72 Some degree of clinical research has demonstrated reductions in antiretroviral serum concentrations in patients who have taken garlic and vitamin C.73, 74 Other herbal products such as milk thistle, echinacea species, and goldenseal inhibit CYP450 enzymes in vitro, but do not appear to give rise to a clinically relevant effect.72–76

The effectiveness of HIV therapy should be monitored in patients taking these supplements, particularly St John’s wort. Because of the risk of dangerous interactions, patients prescribed antiretrovirals should be discouraged from using St John’s wort.2

Anticonvulsant medications

An extensive early review has reported that there are numerous plant products that demonstrate anticonvulsant activity.77 Even though there may not be an unequivocal and overwhelming scientific literature for herbal medicines interacting with anticonvulsant medications, there is strong biological plausibility for significant interactions between some herbal medicines (e.g. kava, valerian) and anticonvulsant medications. The Epilepsy Society of Southern New York in the US has cautioned that certain herbs, supplements and alternative medicines can cause or worsen seizures and may interact with pharmaceutical medications (see the table on the website).78 Moreover, many herbal medicines from Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) cultures, for example, have been documented to treat seizures and may have sedative effects, and can interact with other herbal medicines and supplements, as well as prescription medications.79, 80, 81

Sedatives

The 5 most common natural products with a potential for interaction with pharmaceuticals included garlic, valerian, kava, ginkgo, and St John’s wort, and that these herbal medicines accounted for 68% of the potential clinically significant interactions in the survey.82 The study concluded that the 4 most common classes of prescription medications with a potential for interaction with herbal medicines included sedatives, antithrombotic medications, antidepressant agents, and anti-diabetic agents.

A study on the action of Kava in neurotransmission concluded that kava pyrones exhibited a profile of cellular actions that show a large overlap with several mood stabilisers, especially lamotrigine.83

Immunosuppressant medication

A systematic review has concluded that St John’s wort interacts with cyclosporine, causing a decrease of cyclosporine blood levels and leading in several cases to transplant rejection.84 An animal study has demonstrated that the immunosuppressive methotrexate has significant interactions with the eastern Asia herb of the root extract of kudzu (Pueraria lobata).85 The co-administration of the herb with methotrexate significantly decreased the elimination of the drug and resulted in markedly increased exposure of methotrexate to the rats. Other herbs and/or nutrients that have the potential to stimulate the immune system and possibly counter the effects of immunosuppressants and corticosteroids include alfalfa, astragalus, andrographis, baical skullcap, echinacea, ginseng, goldenseal, withania, licorice root, and/or the mineral zinc.

Summary

A recent US report shows that approximately 66% of patients do not tell their medical practitioners about their nutritional/dietary supplement use.86 Patients may not consider nutritional supplements to be legitimate drugs or to carry adverse risks.87 Therefore, all patients should be asked about their use of dietary supplements irrespective of the type of supplement consumed. Clinicians should question their patients openly about their vitamins, herbs, other supplements, teas, tinctures, or natural products that they are consuming. All of these supplements should be treated as other drugs and recorded in the patient record.

1 Kaufman D.W., Kelly J.P., Rosenberg L., et al. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: the Slone survey. JAMA. 2002;287:337-344.

2 Gardiner P., Graham R.E., Legedza A.T., et al. Factors associated with dietary supplement use among prescription medication users. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1968-1974.

3 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. Pub L No 103–417. Online. Available: www.fda.gov/opacom/laws/dshea.html#sec3 (accessed 15 April 2008).

4 Gardiner P., Phillips R., Shaughnessy A.F. Herbal and dietary supplement–drug interactions in patients with chronic illnesses. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):73-78.

5 Sood A., Sood R., Brinker F.J., et al. Potential for interactions between dietary supplements and prescription medications. Am J Med. 2008;121(3):207-211.

6 Hamilton Smith C., Bidlack W.R. Dietary concerns associated with the use of medications. J Am Diet Assoc. 1984;84(8):901-914.

7 Wahlqvist M.L. Nutrition and health problems related to substance abuse and medications. Food and Nutrition. Allen and Unwin; 1997.

8 Zhou S., Chan E., Pan S.Q., et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions of drugs with St John’s wort. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18(2):262-276.

9 Hammerness P., Basch E., Ulbricht C., et al. for the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. St John’s wort: a systematic review of adverse effects and drug interactions for the consultation psychiatrist. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:271-282.

10 Singh Y.N. Potential for interaction of kava and St. John’s wort with drugs. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:108-113.

11 Izzo A.A. Drug interactions with St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): a review of the clinical evidence. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;42:139-148.

12 Markowitz J.S., DeVane C.L. The emerging recognition of herb-drug interactions with a focus on St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). Psychopharmacol Bull. 2001;35:53-64.

13 Peng C.C., Glassman P.A., Trilli L.E., et al. Incidence and severity of potential drug-dietary supplement interactions in primary care patients: an exploratory study of 2 outpatient practices. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(6):630-636.

14 Izzo A.A., Ernst E. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: a systematic review. Drugs. 2001;61:2163-2175.

15 Roots I. Interaction of a herbal extract from St. John’s wort with amitriptyline and its metabolites. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;67:69.

16 Hall S.D., Wang Z., Huang S.M., et al. The interaction between St John’s wort and an oral contraceptive. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74(6):525-535.

17 Will-Shahab L., Bauer S., Kunter U., et al. St John’s wort extract (Ze 117) does not alter the pharmacokinetics of a low-dose oral contraceptive. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(3):287-294.

18 Vaes L.P., Chyka P.A. Interactions of warfarin with garlic, ginger, ginkgo, or ginseng: nature of the evidence. Ann Pharmacot. 2000;34:1478-1482.

19 Hu Z., Yang X., Ho P.C., et al. Herb-drug interactions: a literature review. Drugs. 2005;65:1239-1282.

20 Jiang X., Williams K.M., Liauw W.S., et al. Effect of St John’s wort and ginseng on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects [Published correction appears in Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004;58:102. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:592-599.

21 Zhou S., Chan E., Pan S.Q., et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions of drugs with St. John’s wort. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18:262-276.

22 Henderson L., Yue Q.Y., Bergquist C., et al. St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): drug interactions and clinical outcomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:349-356.

23 Jiang X., Blair E.Y., McLachlan A.J. Investigation of the effects of herbal medicines on warfarin response in healthy subjects: a population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling approach. J Clin Pharm. 2006;46:1370-1378.

24 Kennedy D.O., Jackson P.A., Haskell C.F., Scholey A.B. Modulation of cognitive performance following single doses of 120 mg Ginkgobiloba extract administered to healthy young volunteers. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(8):559-566.

25 Robertson S.M., Davey R.T., Voell J., et al. Effect of Ginkgo biloba extract on lopinavir, midazolam and fexofenadine pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(2):591-599.

26 Jiang X., Williams K.M., Liauw W.S., et al. Effect of ginkgo and ginger on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:425-432.

27 Mohutsky M.A., Anderson G.D., Miller J.W., et al. Ginkgo biloba: evaluation of CYP2C9 drug interactions in vitro and in vivo. Am J Ther. 2006;13:24-31.

28 Meisel C., Johne A., Roots I. Fatal intracerebral mass bleeding associated with Ginkgo biloba and ibuprofen. Atherosclerosis. 2003;167:367.

29 Abebe W. Herbal medication: potential for adverse interactions with analgesic drugs. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:391-401.

30 Bebbington A., Kulkarni R., Roberts P. Ginkgo biloba: persistent bleeding after total hip arthroplasty caused by herbal self-medication. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:125-126.

31 Pierre S., Crosbie L., Duttaroy A.K. Inhibitory effect of aqueous extracts of some herbs on human platelet aggregation in vitro. Platelets. 16(8), 2005. 469–467

32 Macan H., Uykimpang R., Alconcel M., et al. Aged garlic extract may be safe for patients on warfarin therapy. J Nutr. 2006;136:793S-795S.

33 Beckert B.W., Concannon M.J., Henry S.L., et al. The effect of herbal medicines on platelet function: an in vivo experiment and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(7):2044-2050.

34 Yuan C.S., Wei G., Dey L., et al. Brief communication: American ginseng reduces warfarin’s effect in healthy patients: a randomized, controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):23-27.

35 Garrard J., Harms S., Eberly L.E., Matiak A. Variations in product choices of frequently purchased herbs: caveat emptor. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2290-2295.

36 Yuan C.S., Wei G., Dey L., et al. Brief communication: American ginseng reduces warfarin’s effect in healthy patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:23-27.

37 Buckley M.S., Goff A.D., Knapp W.E. Fish oil interaction with warfarin. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:50-52.

38 Desai D., Hasan A., Wesley R., Sunderland E., Pucino F., Csako G. Effects of dietary supplements on aspirin and other antiplatelet agents: an evidence-based approach. Thromb Res. 2005;117:87-101.

39 Bender N.K., Kraynak M.A., Chiquette E., Linn W.D., Clark G.M., Bussey H.I. Effects of marine fish oils on the anticoagulation status of patients receiving chronic warfarin therapy. J Thromb Thrombol. 1998;5:257-261.

40 Harris W.S. Expert opinion: omega-3 fatty acids and bleeding-cause for concern? Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(6A):44C-46C.

41 Celestini A., Pulcinelli F.M., Pignatelli P., et al. Vitamin E potentiates the antiplatelet activity of aspirin in collagen stimulated platelets. Haematologica. 2002;87:420-426.

42 Kim J.M., White R.H. Effect of vitamin E on the anticoagulant response to warfarin. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:545-546.

43 Booth S.L., Golly I., Sacheck J.M., et al. Effect of vitamin E supplementation on vitamin K status in adults with normal coagulation status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:143-148.

44 Dereska N.H., McLemore E.C., Tessier, et al. Short-term, moderate dosage vitamin E supplementation may have no effect on platelet aggregation, coagulation profile, and bleeding time in healthy individuals. J Surg Res. 2006;132:121-129.

45 Bagchi D., Sen C.K., Bagchi M., Atalay M. Anti-angiogenic, antioxidant, and anti-carcinogenic properties of a novel anthocyanin-rich berry extract formula. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2004;69(1):75-80.

46 Seeram N.P., Adams L.S., Zhang Y., et al. Blackberry, black raspberry, blueberry, cranberry, red raspberry, and strawberry extracts inhibit growth and stimulate apoptosis of human cancer cells in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(25):9329-9339.

47 Bagchi D., Roy S., Patel V., et al. Safety and whole-body antioxidant potential of a novel anthocyanin-rich formulation of edible berries. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;281(1–2):197-209.

48 Boivin D., Blanchette M., Barrette S., Moghrabi A., Béliveau R. Inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and suppression of TNF-induced activation of NFkappaB by edible berry juice. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(2):937-948.

49 Seeram N.P. Berry fruits: compositional elements, biochemical activities, and the impact of their intake on human health, performance, and disease. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(3):627-629.

50 Greenblatt D.J., von Moltke L.L., Perloff E.S., et al. Interaction of flurbiprofen with cranberry juice, grape juice, tea, and fluconazole: in vitro and clinical studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:125-133.

51 Li Z., Seeram N.P., Carpenter C.L., et al. Cranberry does not affect prothrombin time in male subjects on warfarin. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(12):2057-2061.

52 Pham D.Q., Pham A.Q. Interaction potential between cranberry juice and warfarin. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(5):490-494.

53 Tannergren C., Engman H., Knutson L., et al. St John’s wort decreases the bioavailability of R- and Sverapamil through induction of the first-pass metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;75:298-309.

54 Sugimoto K., Ohmori M., Tsuruoka S., et al. Different effects of St John’s wort on the pharmacokinetics of simvastatin and pravastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70:518-524.

55 Portoles A., Terleira A., Calvo A., et al. Effects of Hypericum perforatum on ivabradine pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: an open-label, pharmacokinetic interaction clinical trial. J Clin Pharm. 2006;46:1188-1194.

56 Henderson L., Yue Q.Y., Bergquist C., et al. St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): drug interactions and clinical outcomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:349-356.

57 Johne A., Brockmoller J., Bauer S., Maurer A., Langheinrich M., Roots I. Pharmacokinetic interaction of digoxin with an herbal extract from St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). Clin Pharm Ther. 1999;66:338-345.

58 Tian R., Koyabu N., Morimoto S., et al. Functional induction and de-induction of P-glycoprotein by St. John’s wort and its ingredients in a human colon adenocarcinoma cell line. Drug Metab Disp. 2005;33:547-554.

59 McRae S. Elevated serum digoxin levels in a patient taking digoxin and Siberian ginseng. CMAJ. 1996;155:293-295.

60 Petchetti L., Frishman W.H., Petrillo R., et al. Nutriceuticals in cardiovascular disease: psyllium. Cardiol Rev. 2007;15(3):116-122.

61 Etman M. Effect of a bulk forming laxative on the bioavailablility of carbamazepine in man. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1995;21:1901-1906.

62 Perlman B.B. Interaction between lithium salts and ispaghula husk. Lancet. 1990;335:416.

63 Walker A.F., Marakis G., Simpson E., et al. Hypotensive effects of hawthorn for patients with diabetes taking prescription drugs: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(527):437-443.

64 Sierra M., Garcia J.J., Fernandez N., et al. Therapeutic effects of psyllium in type 2 diabetic patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:830-842.

65 Ziai S.A., Larijani B., Akhoondzadeh S., et al. Psyllium decreased serum glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin significantly in diabetic outpatients. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:202-207.

66 Yeh G.Y., Eisenberg D.M., Kaptchuk T.J., et al. Systematic review of herbs and dietary supplements for glycemic control in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1277-1294.

67 Kiefer D., Pantuso T. Panax ginseng. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(8):1539-1542.

68 Shimizu K., Ozeki M., Tanaka K., et al. Suppression of glucose absorption by some fraction extracted from gymnema silvestre leaves. J Vet Med Sci. 1997;59:245-262.

69 Inayat-Ur-Rahman, Malik S.A., et al. Serum sialic acid changes in non-insulin-dependant diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) patients following bitter melon(Momordica charantia) and rosiglitazone (Avandia)treatment. Phytomedicine. 2009 Apr 9.

70 [No authors listed] Momordica charanti a (bitter melon). Monograph. Altern Med Rev. 2007;12(4):360-363.

71 Raju J., Gupta D., Rao A.R., et al. Trigonellafoenum graecum (fenugreek) seed powder improves glucose homeostasis in alloxan diabetic rat tissues by reversing the altered glycolytic, gluconeogenic and lipogenic enzymes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;224(1–2):45-51.

72 Van den Bout-van den Beukel C.J., Koopmans P.P., et al. Possible drug-metabolism interactions of medicinal herbs with antiretroviral agents. Drug Metab Rev. 2006;38(3):477-514.

73 Lee L.S., Andrade A.S., Flexner C. Interactions between natural health products and antiretroviral drugs: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1052-1059.

74 Gallicano K., Foster B., Choudhri S. Effect of short-term administration of garlic supplements on single-dose ritonavir pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:199-202.

75 Mills E., Montori V., Perri D., et al. Natural health product–HIV drug interactions: a systematic review. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:181-186.

76 van den Bout-van den Beukel C.J., Koopmans P.P., et al. Possible drug-metabolism interactions of medicinal herbs with antiretroviral agents. Drug Metab Rev. 2006;38:477-514.

77 Chauhan A.K., Dobhal M.P., Joshi B.C. A review of medicinal plants showing anticonvulsant activity. Ethnopharmacol. 1988;22(1):11-23.

78 Epilepsy Society of Southern New York in the US. Online. Available: www.essny.org/images/Herbalchart.pdf (accessed April 2009).

79 Elferink J.G.R. Epilepsy and its treatment in the ancient cultures of America. Epilepsia. 1999;40:1041-1046.

80 Kim I.J., Kang J.K., Lee S.A. Factors contributing to the use of complementary and alternative medicine by people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:620-624.

81 Lai C.W., Huang X., Lai Y.H.C., Zhang Z., Liu G., Yang M.Z. A survey of public awareness, understanding and attitudes toward epilepsy in Henan province,. China. Epilepsia. 1990;31:182-187.

82 Dalla Corte C.L., Fachinetto R., Colle D., et al. Potentially adverse interactions between haloperidol and valerian. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(7):2369-2375.

83 Grunze H., Langosch J., Schirrmacher K., et al. Kava pyrones exert effects on neuronal transmission and transmembraneous cation currents similar to established mood stabilizers–a review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25(8):1555-1570.

84 Ernst E. St John’s Wort supplements endanger the success of organ transplantation. Arch Surg. 2002;137(3):316-319.

85 Chiang H.M., Fang S.H., Wen K.C., et al. Life-threatening interaction between the root extract of Pueraria lobata and methotrexate in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;209(3):263-268.

86 Kennedy J., Wang C.C., Wu C.H. Patient Disclosure about Herb and Supplement Use among Adults in the US. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008;5(4):451-456.

87 Gardiner P., Graham R.E., Legedza A.T., et al. Factors associated with dietary supplement use among prescription medication users. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1968-1974.