8 Hepatobiliary disease

Jaundice

Classification

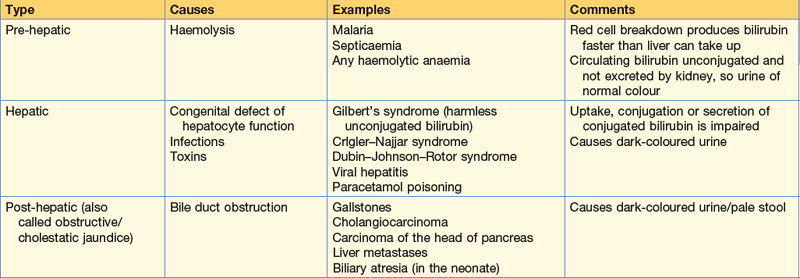

Jaundice is due to elevated bilirubin in blood (upper limit of normal is 17 µmol/L). Jaundice may be pre-hepatic, hepatic or post-hepatic (Table 8.1).

Investigations

Blood tests

| Alkaline phosphatase | Aspartate and alanine transferases | |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatocellular damage | ↑ | ↑↑↑ |

| Extrahepatic biliary obstruction | ↑↑↑ | ↑ |

Liver infections

Pyogenic liver abscess

Liver abscess is rare. Common organisms include Streptococcus milleri, E. coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus and Bacteroides (see Box 8.1 for causes).

Liver tumours

Gallstones (cholelithiasis)

Epidemiology and aetiology

Gallstones occur in 10% of the population over 50. They are more common in females but can affect anyone. Cholesterol is the principal constituent of the majority of stones, usually combined with bile pigment, especially bilirubin. Stones composed of pigment alone account for 5% of the total. Eighty per cent of stones are asymptomatic. Gallstones are caused by a combination of excess cholesterol concentration in bile, stasis or increased bilirubin secretion in bile. Bacterial infection may also play a role. Symptoms of gallstones are related to the complications they cause (Box 8.2).

Gallstone ileus

Occasionally in elderly patients a gallbladder containing stones erodes into the duodenum and stones migrate into the GI tract. A stone that has a greater diameter than the narrowest part of the small bowel (terminal ileum) may impact to cause small bowel obstruction (see p. 88). Biliary symptoms may be minimal.

Pancreatic disease

Developmental anomalies

• Pancreas divisum – most of the pancreas drains into the duodenum through the accessory duct of Santorini

• Annular pancreas – a rare cause of extrinsic compression of the second part of the duodenum, from failure of the two developing pancreatic ducts to fuse

• Heterotopic pancreas – accessory budding of the primitive duodenum results in nodules of pancreatic tissue in abnormal positions, for example stomach, duodenal wall or jejunum.

Physiology

Investigation of pancreatic function is shown in Box 8.3. The imaging methods for the pancreas are shown in Table 8.3.

| Technique | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Abdominal X-ray | Calcification |

| Sentinel loop in acute pancreatitis | |

| Ultrasound | Gland size |

| Presence of gallstones | |

| Cysts | |

| Calcification | |

| Tumour | |

| Duct dilatation | |

| Venous encasement/obstruction | |

| CT | As for ultrasound and is better to define vascular involvement in malignant disease |

| MR | MRI similar to CT but MRCP gives good images of the bile and pancreatic ducts |

| Angiography | Tumour detection |

| Anatomical definition and vascular involvement | |

| Endoscopic ultrasound | Becoming gold standard to give additional information and permit guided biopsy |

| Laparoscopy with or without ultrasound | Valuable for detection of small liver and peritoneal metastases |

Note: percutaneous biopsy under image control can be done to determine the nature of pancreatic swellings.

MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis

Both endocrine and exocrine function, as well as structure of the gland, return to normal after resolution of the attack unless complications occur. The aetiology of pancreatitis is shown in Table 8.4.

| Cause | Possible mechanism |

|---|---|

| Gallstones | Duodenopancreatic reflux Ampullary obstruction with infected bile reflux into pancreatic duct |

| Alcohol | Unknown |

| Iatrogenic: |

? High-pressure injury

? Obstruction to duct

Acute pancreatitis

Assessment of severity

Clinical assessment at presentation is unreliable at predicting the course of the illness. Remarkably well-looking patients with serum amylase >1000 can deteriorate suddenly, and desperately sick-looking individuals can recover quickly. For this reason scoring systems have been developed which allow low- and high-risk patients to be identified. The most commonly used scoring system is the Glasgow method, summarised in Table 8.5. All patients with a serum amylase over 1000 should have their Glasgow criteria established and repeated daily to monitor recovery.

Table 8.5 The Glasgow criteria to gauge severity of pancreatitis

| Factor | Level |

|---|---|

| Age | >55 years |

| Leucocytosis | >15 × 109/L |

| Blood urea concentration | >16 mmol/L (no response to fluid administration) |

| Blood glucose concentration | >10 mmol/L in the non-diabetic |

| Serum albumin concentration | <32 g/L |

| Serum calcium concentration | <2.0 mmol/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | >600 IU/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | >100 IU/L |

| Arterial PO2 | <60 mmHg (8.0 kPa) |

If more than three of the above are positive, the attack is severe.

Prognosis

Complications include hypovolaemia, hypoxia, hypocalcaemia, hyperglycaemia and disseminated intravascular coagulation (Table 8.6). Very occasionally, dead infected areas within the pancreas may be treated by surgery (necrosectomy), which can carry a high mortality rate. Pancreatic lavage is sometimes used.

| System or site | Nature and cause |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Circulatory failure: hypovolaemia |

| Respiratory | Hypoxia and respiratory failure (ARDS): abdominal distension cytokine release bacterial translocation |

| Renal | Acute renal failure – hypovolaemia |

| Haematological | Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| Metabolic | Hypocalcaemia – calcium deposition in areas of fat necrosis |

| Hyperglycaemia – islet cell dysfunction | |

| Acid-base disturbance from tissue necrosis | |

| Nutritional | Muscle wasting/catabolism |

| Sepsis in damaged tissue | Infected retroperitoneal slough – bacterial translocation |

| Pancreatic abscess – infected fluid collection | |

| Retroperitoneum | Fat necrosis – enzyme release |

| Pseudocyst | Effusion with or without duct damage |

| Gastrointestinal | Prolonged paralytic ileus – retroperitoneal inflammation |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding – necrosis of gut wall | |

| Colonic necrosis | |

| Duodenal obstruction | |

| Hepatobiliary | Jaundice/obstruction of common bile duct |

| Vascular | Portal/splenic vein thrombosis |

| Haemorrhage from arterial rupture | |

| SIRS multiorgan dysfunction | Severe pancreatitis causes multiple system failure |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

The spleen

Splenomegaly

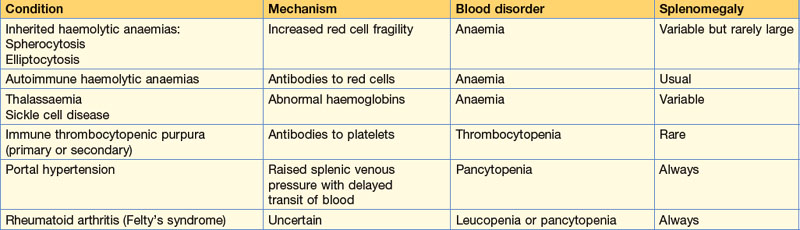

Causes of hypersplenism and possible indications for splenectomy are shown in Table 8.7. Other indications for splenectomy include trauma or as part of other operative procedures, for example gastrectomy, tumours, cysts or more rarely diagnostic procedures such as colonoscopy.

Ruptured spleen

The immediate management of traumatic ruptured spleen (resuscitation) is covered in Chapter 4, p. 66-68. The majority of ruptures are associated with blunt trauma, although splenic hypertrophy may make injury more likely. In the haemodynamically unstable patient laparotomy and splenectomy are indicated, but there is a trend towards conservative management in the stable patient. A CT grading system has developed (see American Association for the Surgery of Trauma guidelines) with Grade 1 = <10% area, subcapsular haematoma to Grade V = ‘Shattered spleen’. Stable patients >55y with isolated Grade 1 or 2 injury can often be managed with close observation.