Hepatectomy

Surgical Principles

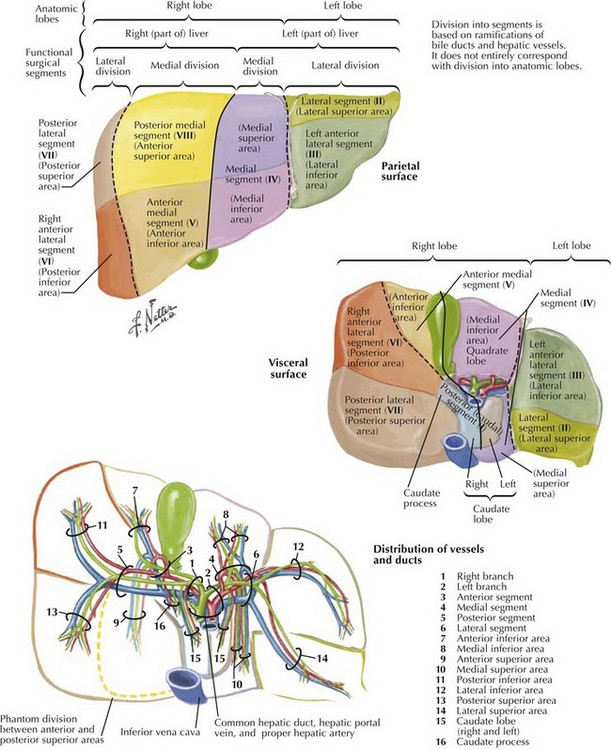

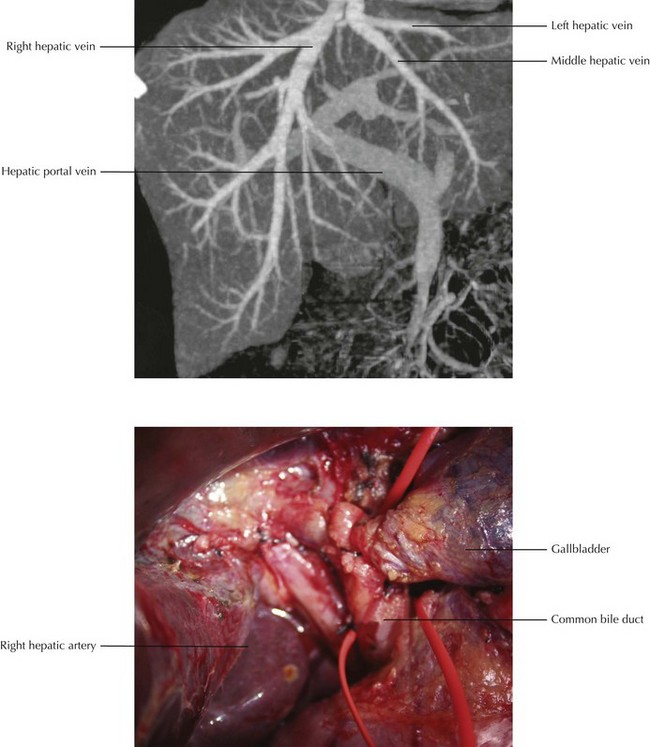

The liver is composed of eight segments based on the portal inflow into the organ (Fig. 14-1). Segments I to IV constitute the left lobe (colored purple, blue, and green on illustration) and segments V to VIII, the right lobe. Preoperative understanding of the patient’s underlying liver anatomy is critical when planning a liver resection. Because of the wide variability in all the hepatic vascular and biliary structures, as well as a considerable amount of variability in the relative sizes of the right and left lobes, imaging is performed to delineate the key structures that may be encountered during the resection (Fig. 14-2). The most useful studies are triple-phase computed tomography or a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging with contrast (Fig. 14-3).

FIGURE 14–3 Hepatic artery: magnetic resonance image and surgical view.

(CT image from Kamel IR, Liapi E, Fishman E. Liver and biliary system: evaluation by multidetector CT. Radiol Clin North Am 2005;43(6):977-97.)

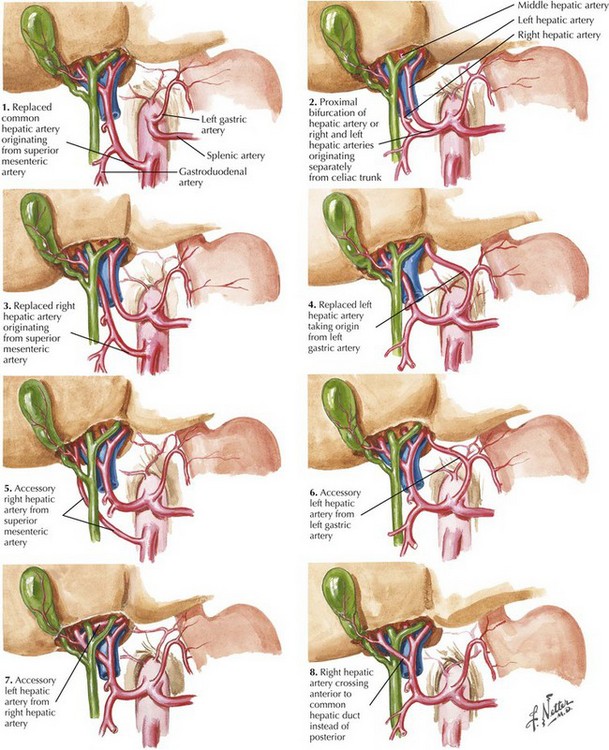

Arterial supply to the liver is through the hepatic artery, which supplies branches to the right and left lobes. Variations in the arterial supply to the liver include an additional, accessory, or replaced right or left hepatic artery and an aberrant origin of the common hepatic artery (Fig. 14-4). The most common variants of the arterial blood supply to the liver include an additional or replaced right hepatic artery from the superior mesenteric artery. This vessel is usually one of the first branches off the superior mesenteric and courses behind the head of the pancreas, posterior to the portal vein and common bile duct, traveling directly into the right lobe of the liver.

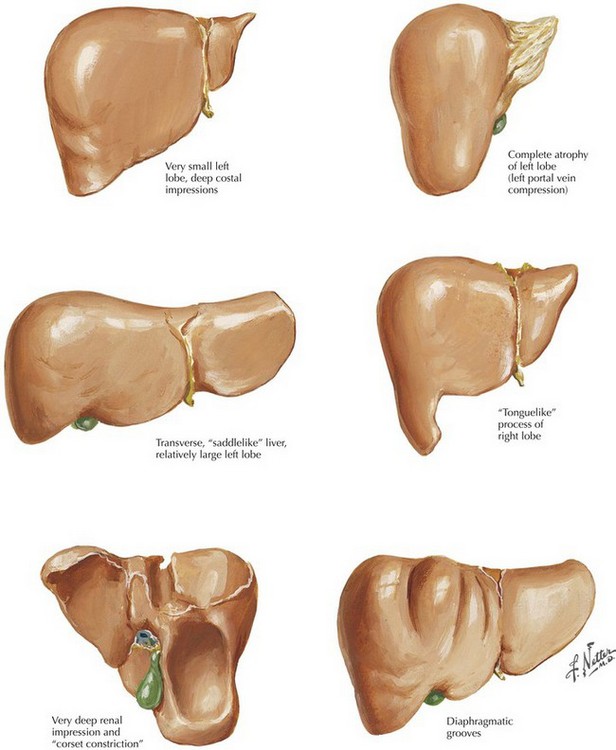

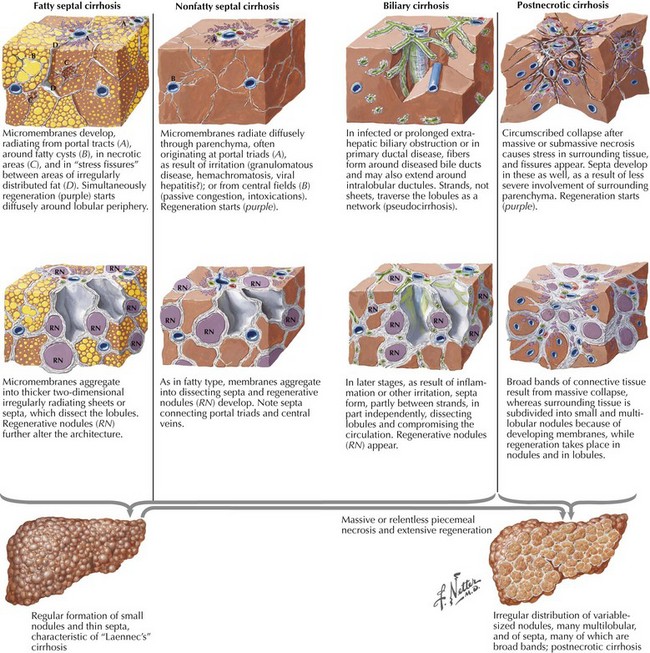

Considerable variations exist in the relative size of the right and left lobes of the liver (Fig. 14-5). In addition to the size of each lobe, the underlying health of the liver parenchyma must also be factored into the decision regarding the minimum amount of liver that must remain for the patient to avoid liver insufficiency. Patients with cirrhosis or hepatic steatosis may need larger residual volumes after resection to maintain adequate function (Fig. 14-6).

Right Hepatic Lobectomy

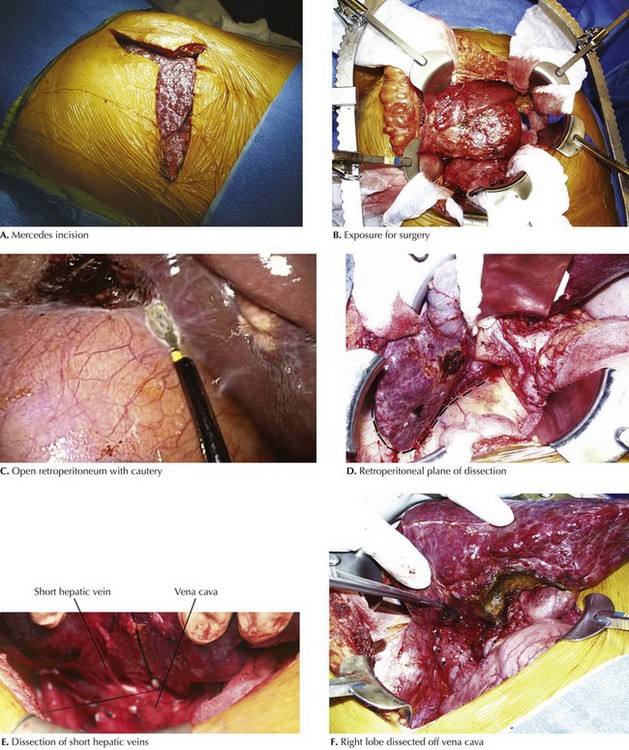

Various types of incisions can provide adequate exposure for a right lobe liver resection. One of the most common is the upper abdominal Mercedes incision, a bilateral subcostal incision with midline extension (Fig. 14-7, A). Other variations include midline, bilateral subcostal, or a right subcostal incision with upper midline extension. Adequate exposure with a self-retaining retractor is essential. To assist with fixation, Bookwalter upright posts can be placed in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) and in the left lower quadrant. This allows two-point fixation to the large ring and assists in optimization of surgical exposure (Fig. 14-7, B).

The liver dissection is begun in the hilum by mobilizing the gallbladder off the liver bed. The lateral border between segments IV and V approximates the dissection plane between the right and left lobes of the liver. The retroperitoneum and Gerota’s fascia, attached to the posterior right lobe of the liver, are incised to prevent liver lacerations of segments VI and VII, as the mobilization of the right lobe is begun (Fig. 14-7, C and D).

Once the inferior right lobe is free, the triangular ligament is divided along the liver to mobilize the right lobe out of the retroperitoneum. This dissection is continued superiorly to the entrance of the right hepatic vein into the vena cava. This maneuver separates the right lobe from the diaphragm. The dissection is continued posteriorly until the vena cava and short hepatic veins are fully exposed. Small short hepatic veins can be ligated and divided; larger ones can be closed with a 2.5-mm vascular stapler or suture-ligated (Fig. 14-7, E and F).

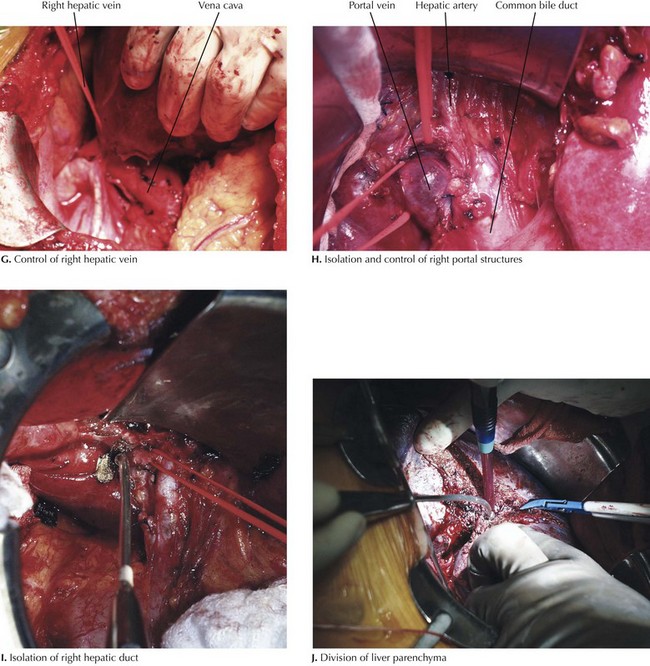

Once all the short hepatic veins are divided, the right hepatic vein can be encircled and controlled with a vessel loop (Fig. 14-8, G). At this time, attention returns to the hilum. The common bile duct can be followed to the bifurcation, and the right hepatic duct can be encircled with a vessel loop. Arterial branches lateral to the bile duct can be identified, ligated proximally and distally, and then divided. The bifurcation of the right and left portal vein branches can now be identified, and the right portal vein can be controlled proximally and distally, divided, and then oversewn, or it can be stapled with a vascular stapler (Fig. 14-8, H and I).

After a 10-minute course of preischemic conditioning with an adequate recovery, the porta hepatis is clamped, the right hepatic vein is taken, and the liver parenchyma is divided (Fig. 14-8, J). Intraoperative ultrasound is useful at this point to mark a plane of dissection lateral to the middle hepatic vein and to mark branches from the right lobe that drain through the middle vein, if present. Liver parenchymal dissection can be done with a crush technique, an ultrasonic device, or high pressure water dissection (ERBE). Other techniques include using a stapler to divide the tissue or a bipolar cautery device.

Left Hepatic Lobectomy

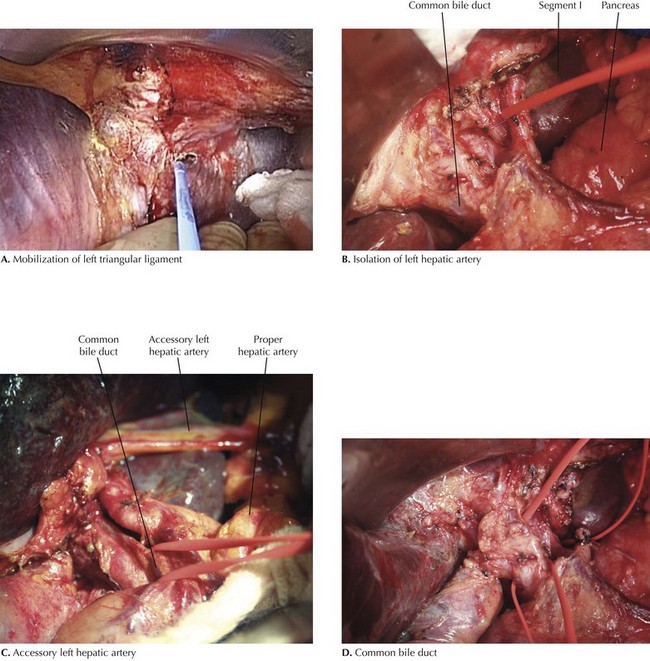

The left lateral segment of the liver is mobilized by dividing the left triangular ligament (Fig. 14-9, A). The left segment is then retracted laterally and the gastrohepatic ligament opened. If present, an accessory or replaced left hepatic artery will travel in the gastrohepatic ligament to the liver. It can be ligated at this point in the dissection; otherwise, the peritoneum over the proximal hepatic artery lymph node is incised and the hepatic artery exposed. The hepatic artery is dissected proximally into the hilum to expose the left hepatic artery (Fig. 14-9, B).

If a formal left hepatectomy is being performed, the left hepatic artery can be ligated after it leaves the main hepatic artery. If segment I is to be left, the artery should be taken after it gives off the branch to segment I. Often, segment IV will have a separate branch off the main hepatic artery. If a formal left hepatic lobectomy is to be performed, the main hepatic artery can be followed to the common bile duct to see if segmental arteries to segment IV are present (Fig. 14-9, C).

Once the left hepatic artery is taken, the gallbladder can be dissected off the liver bed and the cystic artery and duct ligated and divided. The common bile duct is then followed to the bifurcation, and the main left duct is encircled with a vessel loop (Fig. 14-9, D). If segment I is to be left, the duct must be taken distal to the segment I bile duct takeoff. The duct can be taken early if performing a formal left lobectomy. If segmental resections are planned, it is often better to leave the duct until the parenchymal dissection, to facilitate identification of small ducts that travel into segments to be left.

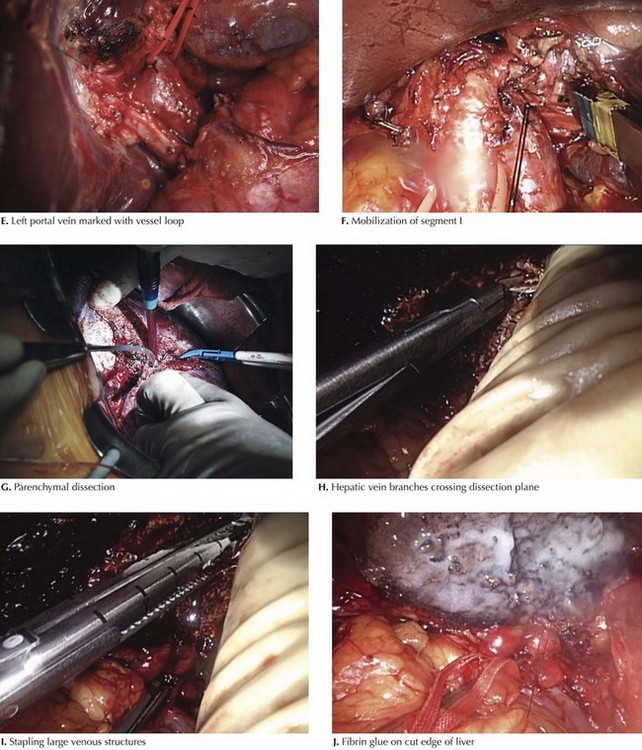

At this time, the main left portal vein can be identified and encircled with a vessel loop (Fig. 14-10, E). The portal vein can be taken with a stapler or can be controlled with clamps, divided, and then oversewn. If the caudate lobe is to be left, the portal branch to the caudate must be saved.

The caudate lobe is mobilized off the vena cava. Short hepatic vein branches are ligated and divided to mobilize the left lobe off the vena cava. Large short hepatic veins can be easily taken with an endovascular GIA stapler. Once the mobilization is complete, the caudate lobe and left segment can be retracted lateral to help expose the left and middle hepatic veins (Fig. 14-10, F). These can be dissected off the vena cava and marked with a vessel loop.

The demarcation plane of the right and left lobes should be evident. Using intraoperative ultrasound, the resection plane lateral to the middle hepatic vein can be marked on the surface of the liver. Using a parenchymal transection technique, the liver parenchyma is divided (Fig. 14-10, G). Larger vessels encountered in the parenchymal dissection can be taken with a stapler or suture-ligated (14-10, I). Once the parenchymal dissection is complete, the cut surface is cauterized with argon beam coagulation and covered with absorbable fibrin glue (14-10, J). A Pringle maneuver or portal inflow occlusion can be performed during the parenchymal dissection if significant bleeding is encountered during the separation of the liver.

Aragon, RJ, Solomon, NL. Techniques of hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3(1):28–40.

Blumgart, LH, Belghiti, J. Surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2007.

Celinski, SA, Gamblin, TC. Hepatic resection nomenclature and techniques. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90(4):737–748.