4 Hemostasis

Chemical Hemostatic Agents

General Principles of Chemical Hemostasis

All of the hemostatic chemicals can be damaging to the eye. Exercise great caution when using chemical agents after a shave or snip (scissors) biopsy on the eyelids or near the eye. The chemical from a dripping cotton-tipped applicator can run into the eye when the biopsy is close to the globe. The Cryo Tweezer described in Chapter 15 is a preferred method for treating skin tags or warts around the eye to avoid chemical exposures. Using electrosurgery for hemostasis can also keep chemicals away from the eye. If aluminum chloride is to be used in this location, dry off the chemical agent on the cotton-tipped applicator with a gauze pad before carefully touching the cotton-tipped applicator to the eyelid or periocular skin. If any chemical does get into the eye, the eye should be flushed immediately.

Aluminum Chloride

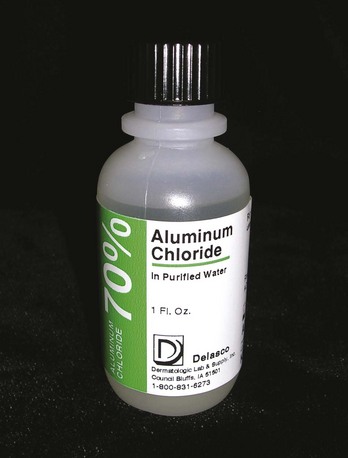

Aluminum chloride comes in strengths from 20% to 70% available in water- or alcohol-based solutions (Figure 4-1). Alcohol alone (anhydrous alcohol) will support a solution of up to 20%, so the stronger concentrations are either in water or a mixture of water and alcohol. I prefer to use aluminum chloride in an aqueous solution because it can be used safely with electrosurgery and comes in higher concentrations. With an alcohol-based solution, it is possible to ignite the alcohol when electrosurgery is performed in the same field. However, drying the field after applying the alcohol-based solution makes it safe to use with electrosurgery.

FIGURE 4-1 70% aluminum chloride in purified water is a useful topical hemostatic agent.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Aqueous aluminum chloride can be ordered as a 35% or 70% solution from Delasco (see the Resources section at the end of the chapter for ordering information). Both are inexpensive and excellent for hemostasis. No studies are available to determine whether one percentage is better than another. I use 70% with good results. These solutions have a 3-year shelf life. Drysol, the brand name of 20% aluminum chloride in anhydrous ethyl alcohol that is sold by prescription to treat hyperhidrosis, also produces hemostasis but is more expensive to purchase and messier to use.

The major advantage of aluminum chloride is that it is a clear solution that does not stain or tattoo the tissue. It does not cause tissue necrosis and does not damage the normal skin surrounding the wound. Aluminum chloride should not be used in deep wounds that will be sutured because it can delay healing and increase scarring.1

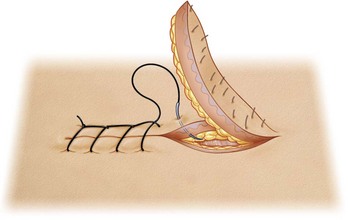

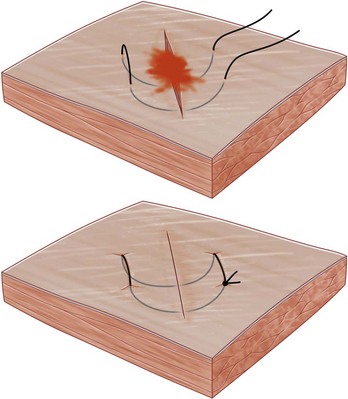

When using aluminum chloride after a shave or punch biopsy, first dry the field with a cotton-tipped applicator or gauze. The aluminum chloride should then be applied to the dry field by rolling or twisting the moist applicator against the open wound (Figure 4-2). Although light pressure may work, it often helps to use heavier pressure while twisting the applicator clockwise and counterclockwise against the area. After a 2- to 4-mm punch biopsy, a dry cotton-tipped applicator can be held with downward pressure against the open hole to dry the field. If sutures are not to be used, the aluminum chloride should be applied with downward pressure and held against the wound until hemostasis is achieved (Figure 4-3).

Electrocoagulation

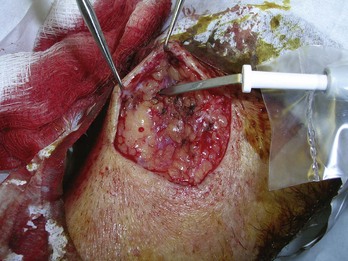

Electrocoagulation is an ideal method for controlling bleeding during surgery. This is especially true with an excision that will be closed with sutures. Electrocoagulation is essential in most elliptical excisions and all flaps. During surgery, electrocoagulation helps to produce a relatively bloodless field (Figure 4-4). This helps to see the landmarks for placing both deep and superficial sutures. Electrocoagulation can prevent postoperative bleeding and hematoma formation. Patients should, however, still be given information on what to do if postoperative bleeding occurs and a number to call if help is needed.

Electrosurgery is an ideal method for hemostasis when tissue destruction is desired. This is true when shaving off a pyogenic granuloma or hemangioma. The electrodestruction diminishes the likelihood of regrowth of vascular tissue while achieving hemostasis. Another example of this is during electrodesiccation and curettage of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The electrodesiccation simultaneously destroys malignant tissue and produces hemostasis. (See Chapter 14, Electrosurgery, for further information on this procedure.)

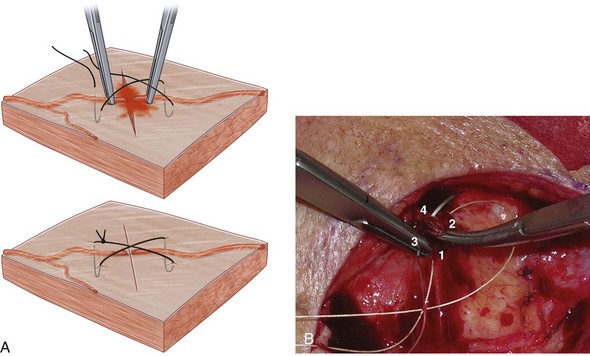

In surgical wounds that need closure, it is important not to use so much electrocoagulation that it produces large areas of char and tissue necrosis. This can increase the risk of wound infection. When a vessel is not responding to electrocoagulation, use a suture. One easy method is to use an absorbable suture with a small figure-of-eight suture around the vessel (Figure 4-5). For example, if you are already using Vicryl for your deep sutures, just use this for the hemostatic stitch. The U-suture (square suture) is another method of obtaining hemostasis with a deep absorbable suture (Figure 4-6).

Electrosurgical Equipment and Its Use

Modern electrosurgical equipment uses an alternating current transferred to the patient through cold electrodes. The tissue is heated through tissue resistance to the current. The current used can range from 0.5 to 4 MHz (radio-frequency). The various types of electrosurgical units are covered in detail in Chapter 14.

Regardless of the type of unit used, there are four major ways to produce electrocoagulation:

Working in a Bloody Field

Bipolar forceps have the advantage of working in a bloody field that is not entirely dry (Figure 4-7). It is still best to dry the field as much as possible, but the current can still pass through the bleeding tissue despite the presence of blood. The ball electrode on the Surgitron can also work in a bloody field (Figure 4-8). When a standard electrode is not working because the field has too much blood, it may help to grasp the bleeding tissue with a hemostat or forceps and direct the current through the instrument to stop the bleeding. The bipolar forceps is the safest method to use in a patient with a pacemaker or implantable defibrillator (see Chapter 14, Electrosurgery).

In Figure 4-9, a pyogenic granuloma was just shaved off the lip of a postpartum woman. A dry cotton-tipped applicator was rolled ahead of the electrode with pressure to dry the field for electrocoagulation with a Hyfrecator electrode. Because this was a very vascular lesion, the electrocoagulation was applied as the cotton-tipped applicator was lifted from the bleeding site.

To summarize, electrocoagulation should be used in the following situations:

Mechanical Hemostasis: Pressure and Sutures

After suturing an elliptical excision, it is wise to apply a pressure dressing to decrease the risk of hematoma formation. This can be left in place for 24 hours and is described further in Chapter 35, Wound Care. We recommend that patients apply direct pressure for 5 to 10 minutes by the clock if postoperative bleeding occurs at home. Increasingly longer periods of time can be attempted as needed. Of course, if the bleeding continues patients will need to access direct care.

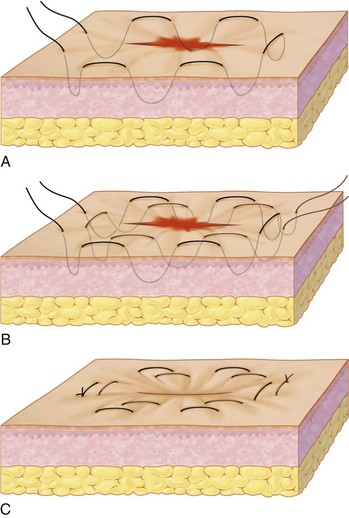

In skin surgery, blood vessels may require tying off. It is usually quicker to use the electrosurgery unit for small blood vessels, with the exception of superficial large arteries such as labial or temporal arteries. These vessels can be clamped with a small hemostat and tied off with absorbable sutures. The figure-of-eight suture and U-shaped suture are useful in this setting (Figures 4-5 and 4-6). Horizontal mattress sutures can be used to stop oozing on the edges of the wound and achieve wound eversion (Figure 4-10).

FIGURE 4-10 A horizontal mattress suture can be used to minimize oozing at the cut edges.

(From Robinson J, Hanke W, Sengelmann R, Siegel D. Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2010.)

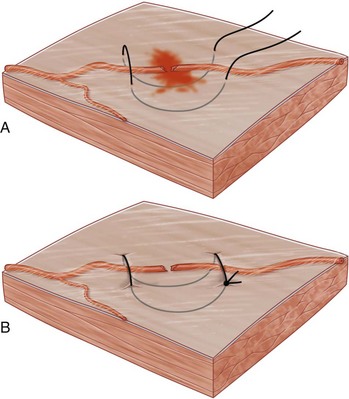

Purse String Stitch

The purse string stitch is depicted in Figure 4-11. A single purse-string suture may be tried at first. A double purse-string suture can be used when other methods fail (Figure 4-11). A 3-0 or 4-0 Prolene suture with at least a 16-mm needle is useful for this technique. The first purse string is placed around the central lesion, with both ends of the suture terminating on one side of the lesion. The second purse string is begun on the opposite end of the first suture and placed around the central lesion. Hemostasis is achieved as both purse-string ends are cinched tight, tamponading the vessels peripheral to the centrally excised lesion.3

Locked Stitch

A running locked suture (Figure 4-12) provides more hemostasis than a running suture that is not locked. In most skin surgery the locking is not needed and increases the risk of necrosis of the wound edges. When bleeding is continuing despite other methods, the benefits outweigh the risks of locking the sutures.

Using Tourniquets and Clamps to Prevent Bleeding

A chalazion clamp was designed to keep a bloodless field on the eyelid when removing a chalazion. It also can be used on the lip to provide hemostasis during surgery (Figure 4-13). A finger tourniquet can be made with a surgical glove to create a bloodless field for finger surgery (Figure 4-14).

Conclusion

Many techniques are available to control bleeding during and after surgery. Judicious application of these hemostatic methods can save time, minimize complications, and maximize the cosmetic outcome of surgery by reducing unnecessary tissue destruction. A summary of recommended hemostasis methods for various procedures is given in Table 4-1.

TABLE 4-1 Recommended Hemostasis Methods for Various Procedures

|

Procedure |

Hemostasis Method |

|---|---|

| Shave biopsy | Aluminum chloride; light electrocoagulation if this fails. |

| Punch biopsy | If sutured: suturing usually stops bleeding but pressure and/or electrocoagulation may also be needed. |

| Elliptical excision | If not sutured: pressure, aluminum chloride, and electrosurgery if needed. |

| External pressure and electrocoagulation to produce dry field. | |

| Tying off of vessels and bleeding areas as needed. | |

| Closing with sutures. | |

| Applying external pressure dressing. | |

| Note: Chemical agents should not be used. | |

| Curettage | Aluminum chloride or electrocoagulation. |

| Scissor surgery | Aluminum chloride or electrocoagulation (snip surgery). |

| Incision and drainage | Packing of the wound, which produces hemostasis by pressure. |

Resources

Chemical agents and electrosurgery equipment can be ordered from the Delasco Dermatologic Buying Guide (800-831-6273; www.delasco.com) and from some of the other resources listed in Chapter 2.

1. Olmstead PM, Lund HZ, Leonard DD. Monsel’s solution: a histologic nuisance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:492-498.

2. Daniels J. Is silver nitrate the best agent for management of umbilical granulomas? Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(5):432.

3. Nguyen T. Hemostasis. In: Robinson J, Hanke W, Sengelmann R, Siegel D, editors. Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:245-258.