61 Hematuria and Proteinuria

Hematuria

Etiology and Pathogenesis

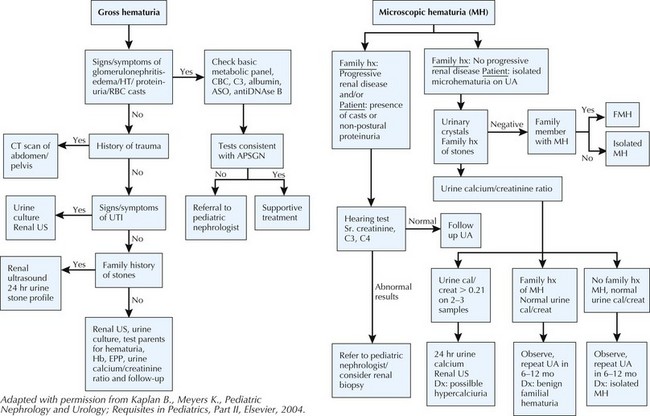

Table 61-1 and Box 61-1 provide a comprehensive differential diagnoses list for hematuria.

Table 61-1 Distinguishing Features of Glomerular and Nonglomerular Hematuria

| Feature | Glomerular | Nonglomerular |

|---|---|---|

| History | ||

| Burning on micturition | No | Urethritis, cystitis |

| Systemic complaints | Edema, fever, pharyngitis, rash, arthralgias | Fever with UTIs; pain with calculi |

| Family history | Deafness in Alport syndrome, renal failure | Usually negative except with calculi |

| Physical Examination | ||

| Hypertension | Often | Unlikely |

| Edema | Sometimes present | No |

| Abdominal mass | No | Wilms’ tumor, polycystic kidneys |

| Rash, arthritis | SLE, HSP | No |

| Urine analysis | ||

| Color | Brown, tea or cola colored | Bright red or pink |

| Proteinuria | Often | No |

| Dysmorphic RBCs | Yes | No |

| RBC casts | Yes | No |

| Crystals | No | May be informative |

HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; RBC, red blood cell; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Box 61-1 Differential Diagnosis of Hematuria

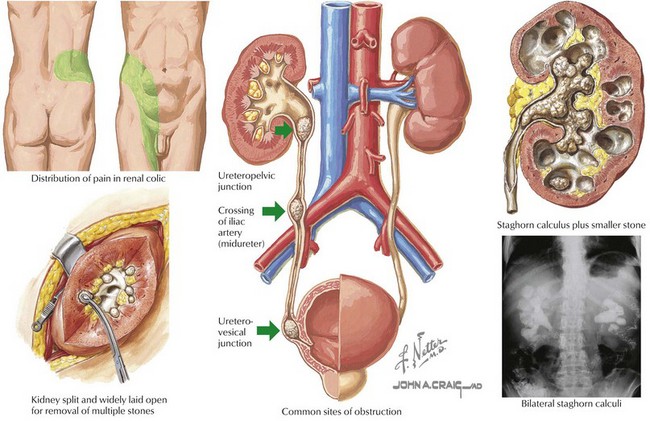

Hypercalciuria and Urolithiasis

Management of these patients is twofold (Figure 61-1). Pain management should be optimized. Surgical intervention or lithotripsy is indicated in cases of urinary obstruction or recurrent stones with superimposed urinary tract infections (UTIs). After the cause has been determined, therapy to prevent stone recurrence can be implemented; this includes increased fluid intake to ensure dilute hypotonic urine, dietary manipulation, and drug therapy in some cases.

Malignancy

Wilms’ tumor is the most common childhood malignancy of the kidney and is discussed further in Chapter 53. Microscopic hematuria is more commonly found than grossly bloody urine, but hematuria as the presenting sign of Wilms’ tumor is rare.

Alport Syndrome

Alport syndrome is a hereditary nephritis associated with sensorineural hearing loss. Alport syndrome presents with persistent or recurrent microscopic or gross hematuria. It is further discussed in Chapter 62.

Clinical Presentation

Proteinuria

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Benign Conditions

Transient Proteinuria

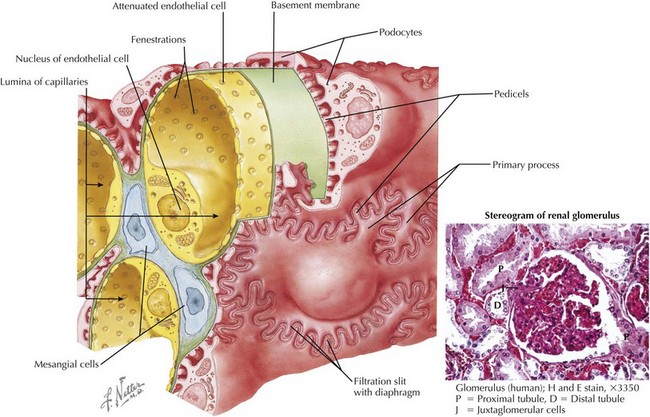

Transient proteinuria is unrelated to renal disease and resolves when the inciting factor disappears. It is rarely greater than 100 mg/dL on the dipstick. Febrile proteinuria usually appears with the onset of fever and resolves by 10 to 14 days. Proteinuria that occurs after exercise usually abates within 48 hours. Transient proteinuria seen with fever, exercise, and congestive heart failure is caused by hemodynamic alterations in renal blood flow that increases the passage of proteins across the glomerular basement membrane (Figure 61-4).

Orthostatic (Postural) Proteinuria

Orthostatic proteinuria is elevated protein excretion that occurs only when the patient is upright. Although the exact mechanism is unclear, orthostatic proteinuria is most likely the result of excessive glomerular filtration of protein (see Figure 61-4). Orthostatic proteinuria is fairly common, accounting for 60% of all causes of childhood proteinuria. The prevalence is even higher among teenagers. Orthostatic proteinuria is an incidental finding. There are no specific clinical features (e.g., edema) and no known cause.

The prognosis for orthostatic proteinuria is thought to be very good.

Pathologic Conditions

Glomerulonephritis

Proteinuria occurs in most glomerular diseases. All forms of glomerulonephritis are discussed in Chapter 62.

Nephrotic Syndrome

Nephrotic syndrome is defined by the presence of proteinuria, edema, hypercholesterolemia, and hypoalbuminemia. Nephrotic syndrome can be primary (isolated to the kidney) or secondary (part of a systemic disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus). Nephrotic syndrome, including minimal change disease, focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis, and membranous nephropathy, is more fully discussed in Chapter 63.

Clinical Presentation and Detection

See Box 61-2 for a list of differential diagnoses. The clinical findings for patients with pathologic causes of proteinuria are discussed in Chapters 62 and 63.

Box 61-2 Differential Diagnosis of Proteinuria

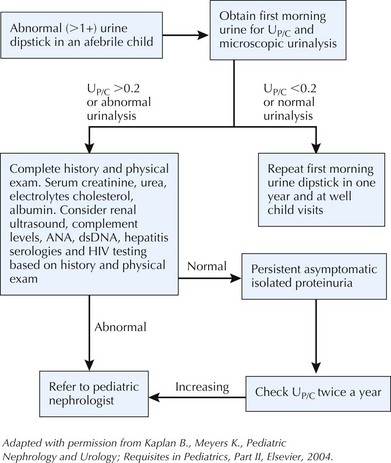

Evaluation and Management

Phase II Workup

See Figure 61-5 for an evaluation algorithm. Split urine samples should be collected, and a 24-hour urinary protein level should be obtained.

Bergstein JM. A practical approach to proteinuria. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:697-700.

Diven SC, Travis LB. A practical primary care approach to hematuria in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:65-72.

Feld LG, Waz WR, Perez LM, et al. Hematuria: an integrated medical and surgical approach. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44(5):1191-1210.

Hogg RJ, Portman RJ, Milliner D, et al. Evaluation and management of proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome in children: recommendations from a pediatric nephrology panel established at the National Kidney Foundation Conference on Proteinuria, Albuminuria, Risk, Assessment, Detection and Elimination (PARADE). Pediatrics. 2000;105:1242-1249.

Meyers KEC. Evaluation of hematuria in children. Urol Clin of N Am. 2004;31(3):559-573.

Yoshikawa N, Kitagawa K, Ohta K, et al. Asymptomatic constant isolated proteinuria in children. J Pediatr. 1991;119(3):375-379.