Chapter 16 Hematuria and Dysuria

1 What is the definition of gross and microscopic hematuria?

Gross hematuria is defined as reddish or pinkish discoloration of the urine with confirmation of red blood cells (RBCs) by microscopy. If the RBCs come from glomeruli, the acidic nature of the urine may change hemoglobin to hematin, causing the urine to appear brownish, tea-colored, or cola-colored.

Gross hematuria is defined as reddish or pinkish discoloration of the urine with confirmation of red blood cells (RBCs) by microscopy. If the RBCs come from glomeruli, the acidic nature of the urine may change hemoglobin to hematin, causing the urine to appear brownish, tea-colored, or cola-colored.

Microscopic hematuria is normal-appearing urine that, when centrifuged, has ≥5 RBCs per high-power field on microscopy.

Microscopic hematuria is normal-appearing urine that, when centrifuged, has ≥5 RBCs per high-power field on microscopy.

3 What can cause a “false-positive” urine dipstick?

Liao JC, Churchill BM: Pediatric urine testing. Pediatr Clin North Am 48:1425–1436, 2001.

4 What is the most likely diagnosis of a child presenting to the emergency department (ED) with “red urine”?

5 Is there a way to determine glomerular versus nonglomerular blood in the urine?

Table 16-1 Glomerular Versus Nonglomerular Blood in the Urine

| Glomerular | Nonglomerular |

|---|---|

| Brown or tea-colored urine | Bright red or pink urine |

| RBC casts | Blood clots |

| Dysmorphic RBCs | Normal RBC morphology |

| Cellular casts | Blood at initiation or termination of urination |

| Proteinuria |

RBC = red blood cell.

Adapted from Kalia A, Travis LB: Hematuria, leukocyturia, and cylindruria. In Edelmann CM (ed): Pediatric Kidney Disease, 2nd ed. Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1992, pp 553–563.

6 What is the differential diagnosis of hematuria in a child?

| Glomerular | Nonglomerular |

|---|---|

| Postinfectious nephritis (poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis) | Urinary tract infection |

| Hemorrhagic cystitis | |

| IgA nephropathy | Urethritis |

| Hereditary nephritis (Alport syndrome) | Sickle cell disease or trait |

| Benign familial hematuria (thin basement membrane disease) | Meatal stenosis |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |

| Exercise-related hematuria | Trauma |

| Subacute endocarditis | Urolithiasis |

| Ventriculoperitoneal shunt nephritis | Hypercalciuria |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Wilms’ tumor |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Polycystic kidney disease |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Urethral prolapse |

| Antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins) | |

| Ureteropelvic junction obstruction | |

| Leukemia | |

| Hemophilia |

Adapted from Kalia A, Travis LB: Hematuria, leukocyturia, and cylindruria. In Edelmann CM (ed): Pediatric Kidney Disease, 2nd ed. Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1992, pp 553–563.

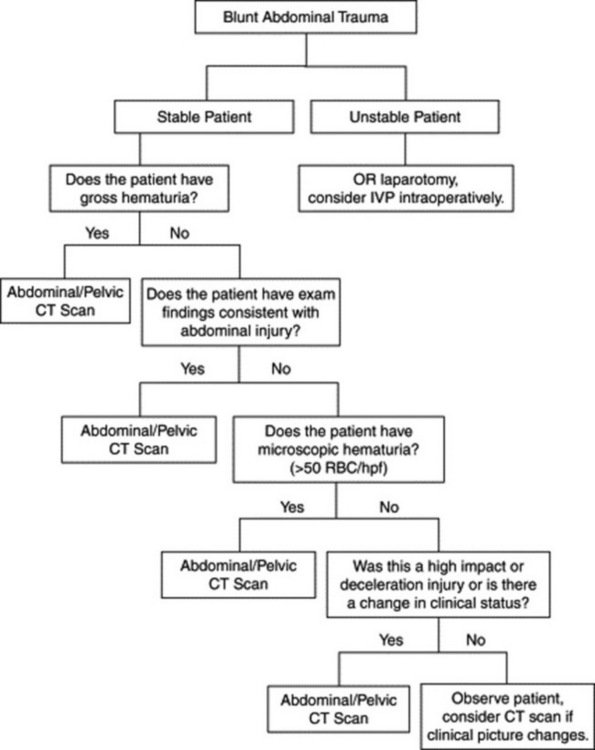

7 How would you evaluate a child with blunt abdominal trauma for renal injury?

10 Describe signs and symptoms associated with hematuria that require urgent/emergent evaluation.

1 Urinary tract infections are the most common cause of hematuria in children.

2 Distinguishing between glomerular and nonglomerular hematuria can help narrow the differential and lead to a diagnosis.

3 Any child with gross hematuria requires emergent evaluation.

4 Any child with hematuria should have a urine dipstick and microscopic urinalysis.

5 Hypercalciuria is the most common cause of pediatric urinary stones.

11 Which laboratory tests are helpful in the evaluation of hematuria?

Patel HP, Bissler JJ: Hematuria in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 48:1519–1535. 2001.

12 Describe the etiology of nephrolithiasis in children.

Gillespie RS, Stapleton FB: Nephrolithiasis in children. Pediatr Rev 25:131–138, 2004.

Hulton SA: Evaluation of urinary tract calculi in children. Arch Dis Child 84:320–323, 2001.

13 How do you diagnose urinary stones in children?

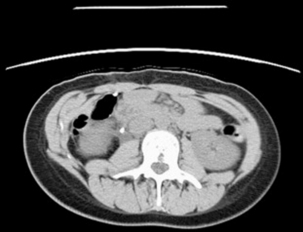

Evaluation and diagnosis should begin with a complete history and physical examination, including a history of urinary infections, current medications, and a detailed family history. A urinalysis and urine culture should be obtained. Microscopic hematuria is present in >90% of children with urinary stones. Infection is commonly seen with stones, so evidence of urinary tract infection does not exclude stones. Renal ultrasonography or nonenhanced helical computed tomography (CT) are the standard methods of diagnosis; they can detect very small stones as well as underlying anatomic abnormalities or alternative diagnoses. Most stones in children are composed of radio-opaque substances and may be seen on plain abdominal radiographs (Fig. 16-2), but the small size of most stones makes this test less sensitive. Intravenous pyelography is another option, although CT has largely replaced it because of increased sensitivity and specificity.

Gillespie RS, Stapleton FB: Nephrolithiasis in children. Pediatr Rev 25:131–138, 2004.

Hulton SA: Evaluation of urinary tract calculi in children. Arch Dis Child 84:320–323, 2001.

17 A child reports dysuria but is afebrile, with no genital lesions, and has a negative urinalysis for pyuria. What are the most probable diagnoses?

19 What parasitic infection should be considered in a traveler or recent immigrant presenting with hematuria or dysuria?

Lischer GH, Sweat SD: 16-year-old boy with gross hematuria. Mayo Clin Proc 77:475–478, 2002.

Ross A, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, et al: Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med 346:1212–1220, 2002.