Hematopoietic and Lymphatic Tissues

Cells of the hematopoietic and lymphatic tissues serve vital functions of host defense, internal homeostasis, and bodily intactness. They all originate from the same stem cell population and in their functional activities interact in various ways (see chapter 1). Disorders in one cell population may thus cause reactions in the other. For this reason, the hematopoietic and lymphatic systems are discussed together. Just as there are a large number of different cell populations with various differentiation stages and functional activities, so are there a multitude of human diseases of the blood and lymphatic systems. The most common and important are discussed in this chapter. The most common leading symptoms of all these diseases are infection, hemorrhage or thrombosis, and anemia.

Neoplastic Lymphatic Disorders

Malignant neoplasias of the lymphatic tissues are collectively identified as malignant lymphomas (MLs) or, when malignant cells circulate in the blood, lymphocytic leukemias. There are 2 major groups of MLs: Hodgkin lymphomas (lymphogranulomatosis) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs). Hodgkin lymphoma, or Hodgkin disease (HD), is distinguished from NHL by its polymorphic features, including certain inflammatory components such as fibrosis and occasional regression simulating nonneoplastic diseases, which eventually may progress to ML. Although it is a lymphatic malignancy, it is accompanied by a large number of associated nonneoplastic cells, which may influence the course and progression of the disease. NHL, by contrast, begins as malignant clonal proliferations. Transition from HD to NHL and combinations of HD with certain types of NHL have been observed (HD and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [CLL] or follicular center cell lymphoma [FCC]; see Table 10-4).

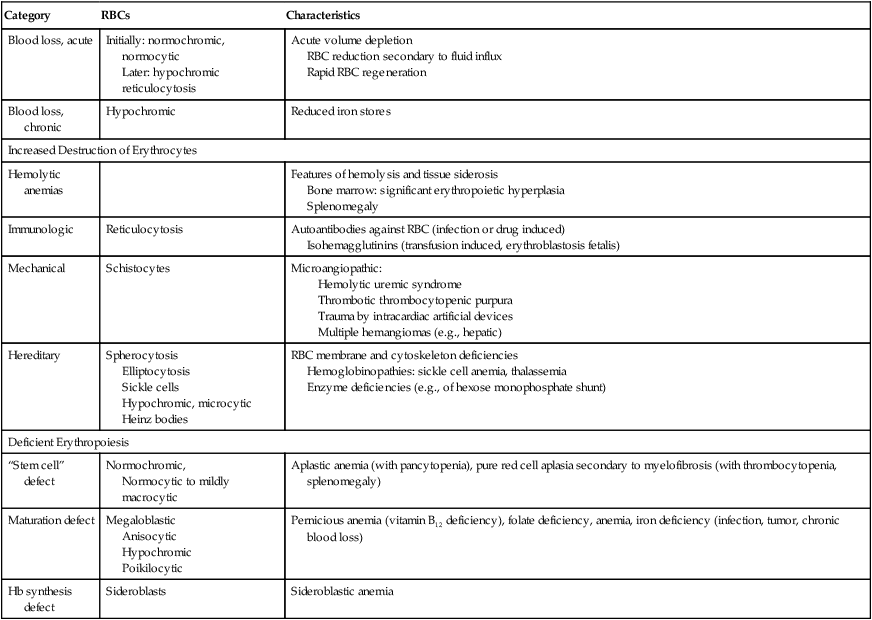

TABLE 10-1

| Category | RBCs | Characteristics |

| Blood loss, acute | Initially: normochromic, normocytic Later: hypochromic reticulocytosis |

Acute volume depletion RBC reduction secondary to fluid influx Rapid RBC regeneration |

| Blood loss, chronic | Hypochromic | Reduced iron stores |

| Increased Destruction of Erythrocytes | ||

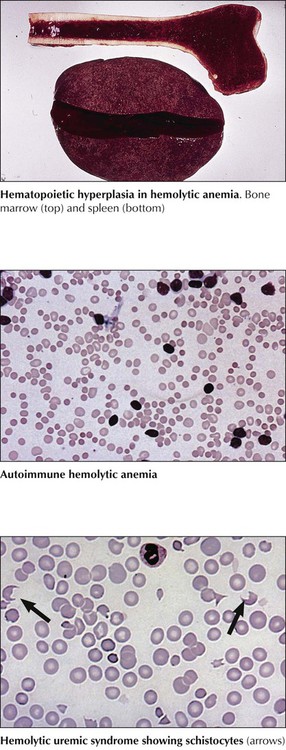

| Hemolytic anemias | Features of hemolysis and tissue siderosis Bone marrow: significant erythropoietic hyperplasia Splenomegaly |

|

| Immunologic | Reticulocytosis | Autoantibodies against RBC (infection or drug induced) Isohemagglutinins (transfusion induced, erythroblastosis fetalis) |

| Mechanical | Schistocytes | Microangiopathic: Hemolytic uremic syndrome Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura Trauma by intracardiac artificial devices Multiple hemangiomas (e.g., hepatic) |

| Hereditary | Spherocytosis Elliptocytosis Sickle cells Hypochromic, microcytic Heinz bodies |

RBC membrane and cytoskeleton deficiencies Hemoglobinopathies: sickle cell anemia, thalassemia Enzyme deficiencies (e.g., of hexose monophosphate shunt) |

| Deficient Erythropoiesis | ||

| “Stem cell” defect | Normochromic, Normocytic to mildly macrocytic |

Aplastic anemia (with pancytopenia), pure red cell aplasia secondary to myelofibrosis (with thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly) |

| Maturation defect | Megaloblastic Anisocytic Hypochromic Poikilocytic |

Pernicious anemia (vitamin B12 deficiency), folate deficiency, anemia, iron deficiency (infection, tumor, chronic blood loss) |

| Hb synthesis defect | Sideroblasts | Sideroblastic anemia |

normochromic: normal color (i.e. normal Hb content); normocytic: normal size and shape of RBC; hemolytic: red cell lysis

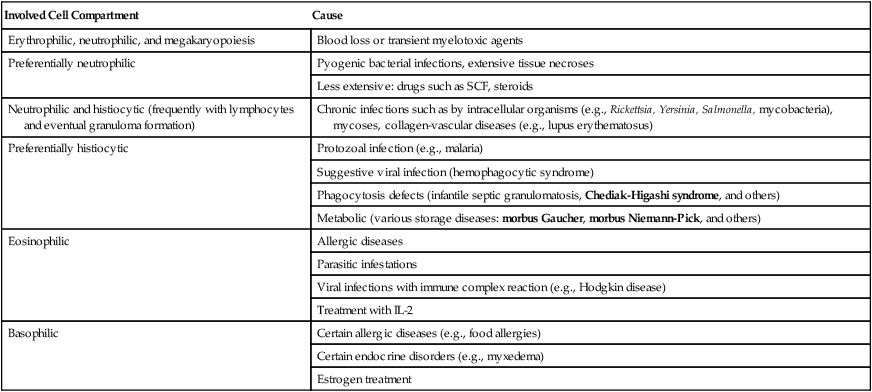

TABLE 10-2

REACTIVE HEMATOPOIETIC HYPERPLASIA (NONLYMPHATIC)

| Involved Cell Compartment | Cause |

| Erythrophilic, neutrophilic, and megakaryopoiesis | Blood loss or transient myelotoxic agents |

| Preferentially neutrophilic | Pyogenic bacterial infections, extensive tissue necroses |

| Less extensive: drugs such as SCF, steroids | |

| Neutrophilic and histiocytic (frequently with lymphocytes and eventual granuloma formation) | Chronic infections such as by intracellular organisms (e.g., Rickettsia, Yersinia, Salmonella, mycobacteria), mycoses, collagen-vascular diseases (e.g., lupus erythematosus) |

| Preferentially histiocytic | Protozoal infection (e.g., malaria) |

| Suggestive viral infection (hemophagocytic syndrome) | |

| Phagocytosis defects (infantile septic granulomatosis, Chediak-Higashi syndrome, and others) | |

| Metabolic (various storage diseases: morbus Gaucher, morbus Niemann-Pick, and others) | |

| Eosinophilic | Allergic diseases |

| Parasitic infestations | |

| Viral infections with immune complex reaction (e.g., Hodgkin disease) | |

| Treatment with IL-2 | |

| Basophilic | Certain allergic diseases (e.g., food allergies) |

| Certain endocrine disorders (e.g., myxedema) | |

| Estrogen treatment |

SCF indicates colony stimulating factor; IL, interleukin.

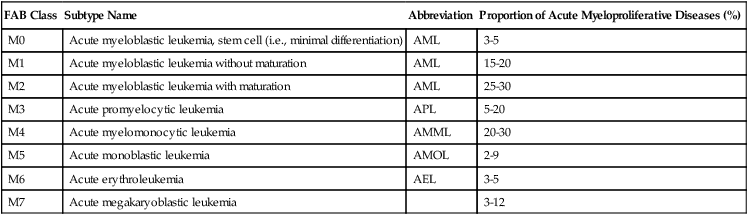

TABLE 10-3

CLASSIFICATION IN SUBTYPES OF ACUTE MYELOPROLIFERATIVE DISEASES*

| FAB Class | Subtype Name | Abbreviation | Proportion of Acute Myeloproliferative Diseases (%) |

| M0 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia, stem cell (i.e., minimal differentiation) | AML | 3-5 |

| M1 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia without maturation | AML | 15-20 |

| M2 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia with maturation | AML | 25-30 |

| M3 | Acute promyelocytic leukemia | APL | 5-20 |

| M4 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | AMML | 20-30 |

| M5 | Acute monoblastic leukemia | AMOL | 2-9 |

| M6 | Acute erythroleukemia | AEL | 3-5 |

| M7 | Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia | 3-12 |

FAB indicates French-American-British classification.

*Acute myeloproliferative diseases are clonal neoplastic disorders of hematopoietic stem cells, the classification of which is determined by their preferential cytologic differentiation.

Adapted from Hoffman R et al. Hematology. Philadelphia: Churchill-Livingstone; 2000.

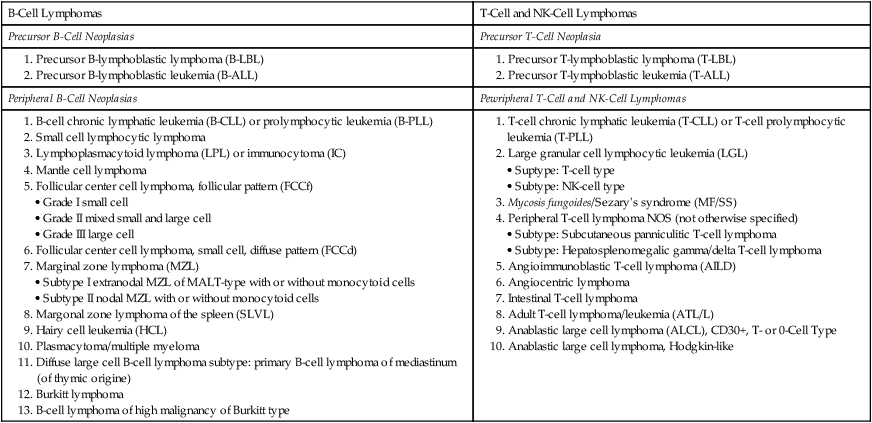

TABLE 10-4

CLASSIFICATION OF LYMPHOMA (NHL) ENTITIES

Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) Classification

| B-Cell Lymphomas | T-Cell and NK-Cell Lymphomas |

| Precursor B-Cell Neoplasias | Precursor T-Cell Neoplasia |

1. B-cell chronic lymphatic leukemia (B-CLL) or prolymphocytic leukemia (B-PLL)

2. Small cell lymphocytic lymphoma

3. Lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma (LPL) or immunocytoma (IC)

5. Follicular center cell lymphoma, follicular pattern (FCCf)

6. Follicular center cell lymphoma, small cell, diffuse pattern (FCCd)

7. Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL)

8. Margonal zone lymphoma of the spleen (SLVL)

10. Plasmacytoma/multiple myeloma

11. Diffuse large cell B-cell lymphoma subtype: primary B-cell lymphoma of mediastinum (of thymic origine)

1. T-cell chronic lymphatic leukemia (T-CLL) or T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL)

2. Large granular cell lymphocytic leukemia (LGL)

3. Mycosis fungoides/Sezary’s syndrome (MF/SS)

4. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma NOS (not otherwise specified)

5. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AILD)

8. Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (ATL/L)

9. Anablastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), CD30+, T- or 0-Cell Type

Classification of anemias by immediate cause is shown in Table 10-1. Acute blood loss initially causes blood volume depletion; normochromic anemia becomes overt 24 to 48 hours later, after some volume is replaced. Chronic blood loss (e.g., in intestinal ulcers, polyposis, hypermenorrhea) with depletion of the body’s iron stores causes hypochromic anemia. Erythrocyte destruction causes several anemias. Immunohemolytic anemia arises spontaneously after infection or drug treatment or in erythroblastosis fetalis, the incompatibility of erythrocyte antigens between an Rh-negative mother and her Rh-positive fetus. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) is caused by mechanical shear forces from fibrin strands in small vessels (hemolytic uremic syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or multiple hemangiomas) or from artificial devices in the bloodstream (e.g., cardiac valvular prostheses). Peripheral blood smears show fragmented erythrocytes (schistocytes, fragmentocytes).

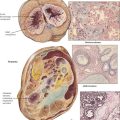

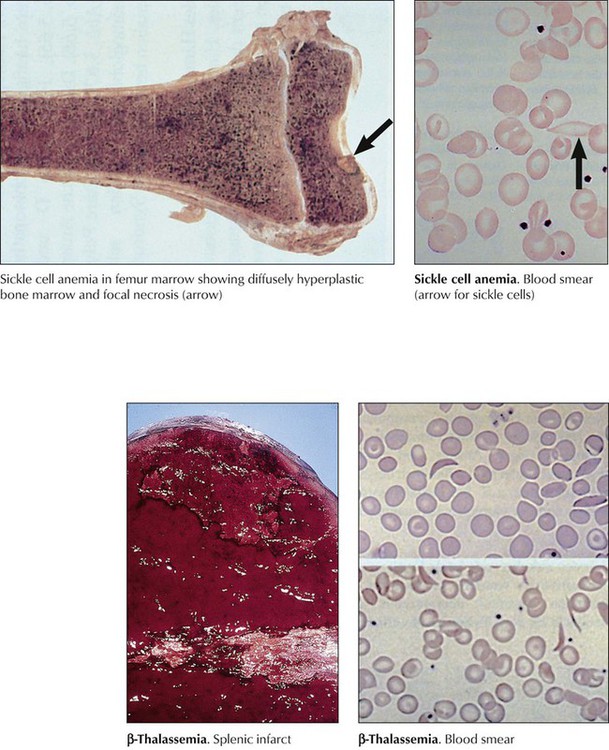

Hereditary anemias with structural abnormalities of RBC membranes, cytoskeleton, or hemoglobin (Hb) show spherocytes (hereditary spherocytosis), elliptocytes (hereditary elliptocytosis), sickle cells (sickle cell anemia), or poikilocytosis, anisocytosis, microcytosis, hypochromasia, and reticulocytosis. Vulnerable RBCs are sequestered in the spleen and undergo hemolysis. Many hereditary anemias thus have clinical features of hemolytic anemia: splenomegaly, bone marrow hyperplasia, and tissue siderosis. Thalassemias entail defective synthesis of Hb α or β chains (α, β-thalassemia). A severe form (Cooley anemia) shows a reduction or absence of Hb β chains, predominance of fetal hemoglobulin, reactive bone marrow hyperplasia and splenomegaly, enhanced iron resorption, and iron overload syndrome (hemosiderosis, hemochromatosis). In sickle cell anemia, rigid sickle cells undergo hemolysis and cause vasoocclusive disease (capillary stasis and thrombosis) with infarcts in many organs.

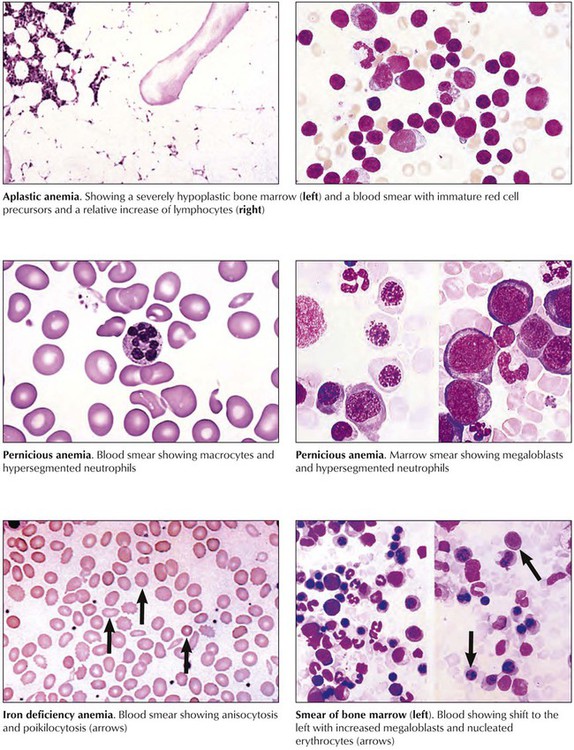

Aplastic anemia is characterized by anemia, neutropenia (reduced number in neutrophils), and thrombocytopenia (reduced number in platelets) and may transform to leukemia. The bone marrow is hypocellular. Patients show pallor, petechial hemorrhages, and increased susceptibility to infection. Pernicious anemia (megaloblastic anemia) arises from a deficiency of vitamin B12, folate, or both secondary to reduced resorption in atrophic gastritis or chronic liver diseases. Myelocytes and megakaryocytes in the bone marrow show nuclear abnormalities (e.g., “horseshoe myelocytes,” hypersegmented megakaryocytes). Sideroblastic anemia is an X chromosome–linked or acquired deficiency of Hb synthesis. It is a hypochromic microcytic anemia with ferric phosphate or hydroxide deposits in mitochondria of erythroblasts (ring sideroblasts). Resistant cases necessitate multiple transfusions and thus may be complicated by iron overload syndrome with secondary hemochromatosis, cardiac failure, and diabetes mellitus.

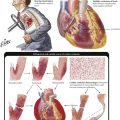

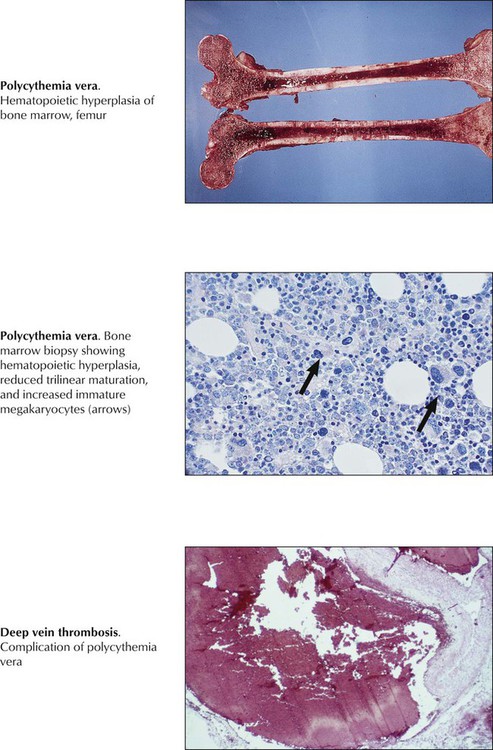

A chronic myeloproliferative disease with autonomous clonal proliferation of myelopoietic stem cells in bone marrow and extramedullary sites (liver, spleen), polycythemia vera (PCV; primary erythrocytosis) must be distinguished from other chronic myeloproliferative diseases, such as chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), primary thrombocythemia (PTH), and osteomyelofibrosis (OMF). The bone marrow in PCV shows panhyperplasia with erythropoietic predominance, depletion of bone marrow iron stores, progressive fibrosis, and clusters of macromegakaryocytes. Clinical features include splenomegaly, erythrocytosis of 6 to 10 million cells/µL, Hb level greater than 20 g/dL, and hematocrit greater than 60%. Serum erythropoietin is reduced. Patients show a typical red facies and report headaches and dizziness. Disturbances in blood flow may result in angina pectoris, claudicatio intermittens, upper intestinal ulcerations, or life-threatening thrombotic complications. Twenty percent to 50% of PCV patients progress to preleukemia and acute leukemia.

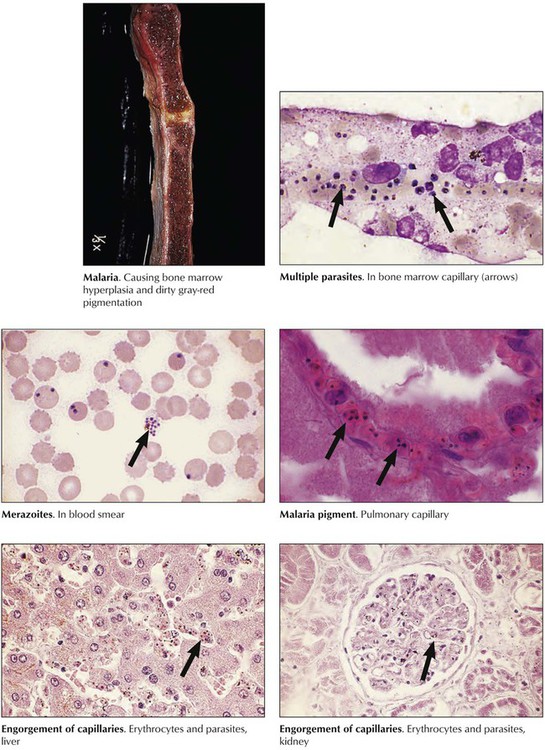

Plasmodium protozoa (P vivax, P malariae, P ovale, and P falciparum) are carried by the female Anopheles mosquito, whose bite transfers sporozoites to the blood. After infecting hepatocytes, they transform to merozoites and infect erythrocytes. The 4 species cause diseases of different cycles and severity. P vivax and P ovale cause tertian malaria, P malariae causes quartan malaria, and P falciparum causes falciparum malaria, the most lethal form. Initial symptoms are anorexia, headache, bone pain, and chills. Episodic destruction of RBCs by schizogony and release of merozoites causes spiking fevers and shaking chills every third day in tertian and falciparum malaria and every fourth day in quartan malaria. Pathologic changes are hemolytic anemia, reticuloendothelial (RE) cell hyperplasia (liver, lymph nodes, spleen), obstruction of capillaries by infected RBCs (lungs, liver, kidneys, bone marrow, brain), and deposits of malaria pigment in RE cells and vascular endothelia.

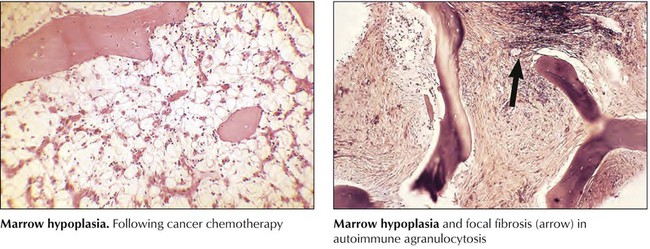

Decrease or loss of peripheral blood neutrophilic WBCs (neutropenia or agranulocytosis) is caused either by enhanced removal or destruction of cells or by their reduced production (i.e., by bone marrow hypoplasia). Increased destruction may result from toxins or infections (e.g., drugs, overwhelming infections), autoimmune reactions (e.g., autoimmune neutropenia or agranulocytosis), or increased removal in enlarged spleens (i.e., hypersplenism with neutrophilic sequestration). In these cases, the bone marrow shows reactive hyperplasia without cytologic abnormalities. In cases of toxic destruction, peripheral blood neutrophils may show toxic granulations in their cytoplasm and hypersegmented or fragmented nuclei. The 3 characteristic clinical consequences of hematopoietic hypoplasia are anemia, hemorrhage (in thrombocytopenia), and infection (in neutropenia or agranulocytosis).

Hematopoietic hyperplasia in the bone marrow and reactive leukocytosis in the blood occur in response to various inflammatory stimuli or to certain cellular and metabolic deficiencies and may progress to simulating neoplasia (leukemoid reaction). Hematopoietic hyperplasia is accompanied by release from the bone marrow of less mature cells (shift to the left) with increased numbers of immature neutrophils, metamyelocytes, or even myelocytes. Different from neoplasia, reactive hyperplasia is usually transient and subsides when the causative stimulus is terminated (Table 10-2).

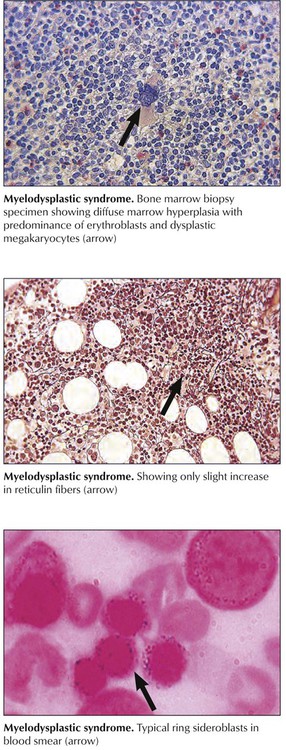

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a form of hematopoietic hyperplasia and dysplasia with peripheral cytopenia. MDS originates from hematopoietic stem cell defects with multiple genetic abnormalities and clonal proliferation of hematopoietic cells, T lymphocytes, and clonal or polyclonal B lymphocytes. Several stages are identified: (1) refractory anemia (RA), with less than 5% blasts in the bone marrow; (2) refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (RARS), with less than 5% blasts; (3) refractory anemia with excess blasts (RAEB), with 5% to 20% bone marrow blasts; and (4) refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation (RAEB-T), with 20% to 30% bone marrow blasts and more than 5% blasts in the blood. Anemia and fatigue are early symptoms, followed by neutropenia, infections, thrombocytopenia, and bleeding. Bone marrow aspirates show a megaloblastic erythropoiesis with ring sideroblasts, increased myeloblasts, and hypolobulated megakaryocytes. Transition to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) occurs in 40% to 50% of advanced cases.

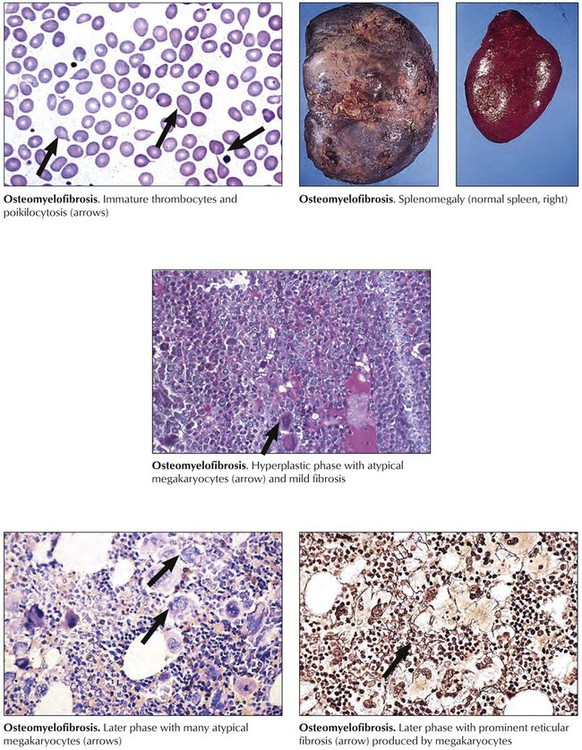

Chronic myeloproliferative diseases, clonal neoplastic disorders with variable myelofibrosis and a terminal blastic phase, include PCV, osteomyelofibrosis, CML, and PTH (primary thrombocythemia). Osteomyelofibrosis, also referred to as agnogenic myeloid metaplasia, myelosclerosis, and idiopathic myeloid metaplasia, occurs primarily in older populations exposed to viral infections or toxic chemicals. Patients report fatigue, fever and night sweats, weight loss, upper abdominal fullness (splenomegaly, hepatomegaly), and bleeding. Peripheral blood shows “teardrop” poikilocytosis (dacryocytes), normoblasts, immature myeloid cells and megathrombocytes with the bone marrow in early hematopoietic hyperplasia, and predominance of megakaryocytes and granulocytes. Megakaryocytes include many pleomorphic giant forms with nuclear atypia, naked nuclei, and cytoplasmic fragments. Life expectancy varies according to risk factors (low Hb level and low WBC count) from 93 months to 13 months.

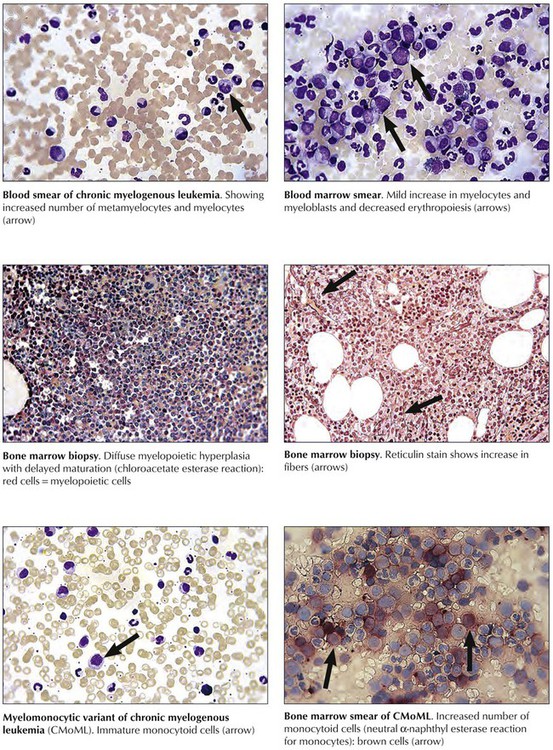

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), another chronic myeloproliferative disease, is defined by myeloid hyperplasia, leukocytosis, basophilia, and splenomegaly. CML is associated with a characteristic chromosomal t(9,22)(q34;q11) translocation, the Philadelphia chromosome, which provides the mutated cells with a proliferative advantage. Clinical features are fatigue, weight loss, sweats, bone pain, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, and petechial hemorrhages. An initial chronic phase of CML (<10% blasts in bone marrow) is followed by an accelerated phase with final inevitable and fatal blast crisis (>30% blasts in the bone marrow with promyelocytes). Variants of CML include chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), which must be distinguished from MDSs. The life expectancy of patients with CML depends on disease progression and type of treatment; 45% to 65% of patients survive 5 years.

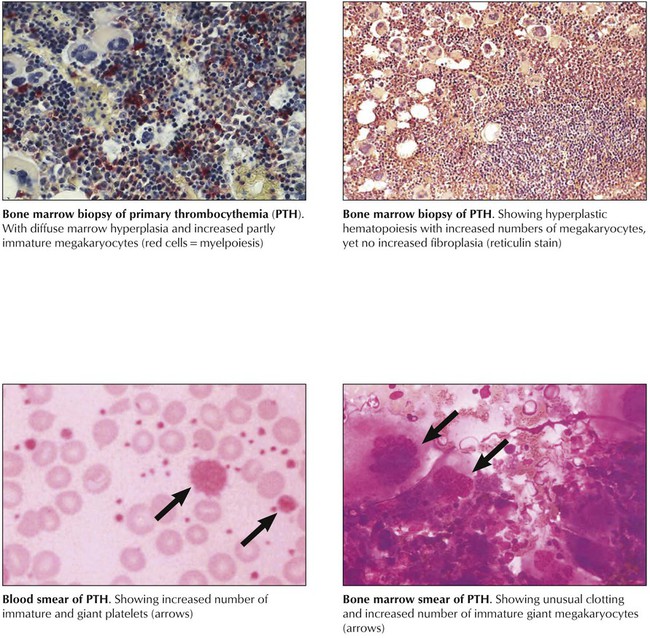

Primary thrombocythemia (PTH) is a chronic myeloproliferative disease with progressive megakaryocytic hyperplasia, peripheral thrombocytosis (>600,000/mL), splenomegaly, and hemorrhagic and thrombotic complications. The bone marrow contains partially clustered giant megakaryocytes and promegakaryocytes with mitoses, cytoplasmic fragments, and prominent emperipolesis (engulfment of a cell by a cell other than phagocytes). Clinical features may include hemorrhagic or thrombotic episodes or both, headache, dizziness, paresthesias, and other neurologic symptoms. Microvascular occlusions cause microinfarcts in several organs and occasional digital gangrene. Large vessel thrombosis occurs most frequently in femoral, renal, coronary, gastrointestinal (GI), and other arteries. In approximately 3% to 10% of patients, blastic transformation with features of myelogenous, myelomonocytic, megakaryocytic, or even lymphoblastic leukemia is reported. The 10-year survival rate for patients with PTH is 65% to 80%.

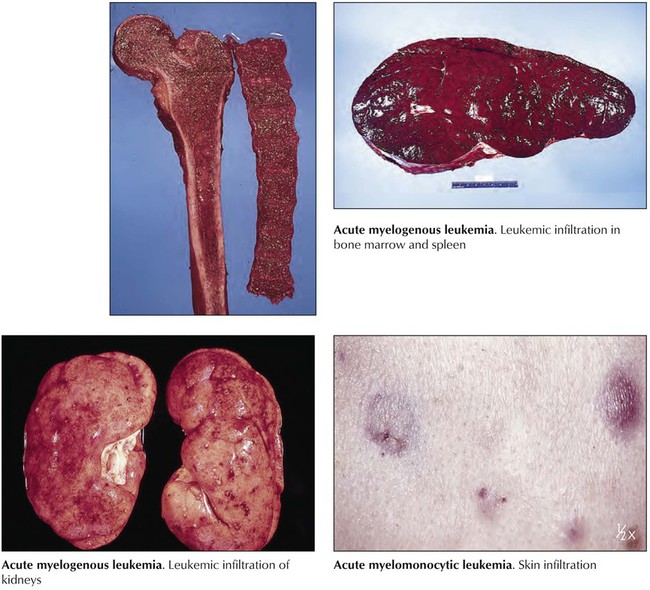

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is an acute myeloproliferative disease (Table 10-3) representing approximately 90% of all acute leukemias. Approximately 22% of cases develop in patients with MDSs. Patients usually present with malaise and fatigue, frequently after a flulike illness, and may have resistant skin infections, unusual pallor, and bleeding from the gums and the nose. Blood smears show leukopenia of 1000 WBCs/mL or excessive leukocytosis up to 200,000 WBCs/mL with increase in immature cells. The liver and the spleen are enlarged and infiltrated by atypical blasts. Additional symptoms result from metabolic and electrolyte derangements (hypokalemia, hypercalcemia), agranulocytosis (necrotizing enterocolitis), or rapid lysis of leukemic blasts (tumor lysis syndrome: urate nephropathy, hyperphosphatemia, muscle cramps, arrhythmias). Survival rates for all AML subtypes combined are 40% at 15 months and approximately 20% at 50 months.

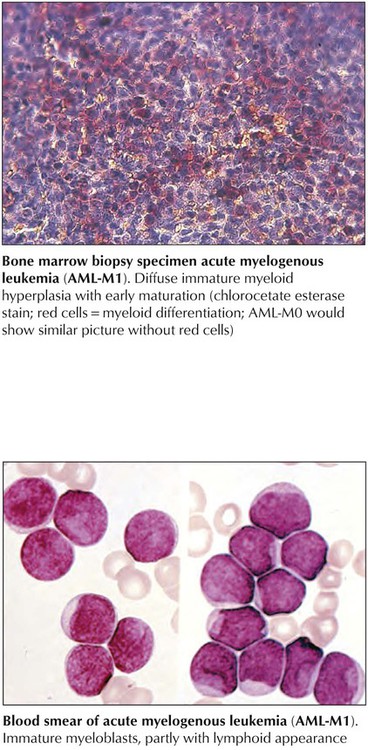

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML)–M0 and AML-M1 constitute the most immature types of AML and can be difficult to distinguish from acute lymphoblastic leukemia or monoblastic or megakaryoblastic leukemia. They present with more than 30% blasts with hardly any positive myeloperoxidase reaction. AML-M0 cells are usually positive for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and CD34 (hematopoietic stem cell marker). AML-M1 types show approximately 10% promyelocytes, suggesting some myelopoietic differentiation. The prognosis is poor. AML-M2 shows signs of maturation beyond promyelocytes. There are more than 30% blasts, and promyelocytes account for 3% to 20% of leukemic cells with occasional maturation of eosinophils and basophils. Maturing cells contain intracytoplasmic red rodlike structures (Auer rods) and stain strongly for chloroacetate esterase and peroxidase enzyme activities. The 50% of patients who have t(8;21) chromosomal translocations have a slightly better prognosis than those without translocations.

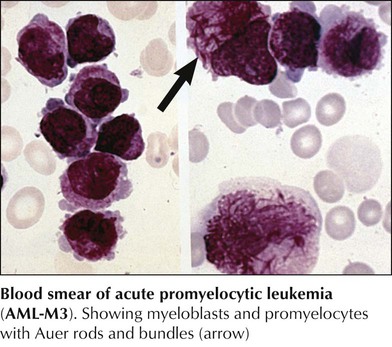

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (AML-M3) is characterized by atypical promyelocytes in the bone marrow and hypergranular cells with multiple Auer rods (Auer bundles). Patients with M3 leukemia are generally younger (median age, 31 years) and have lower WBC counts than patients with more common leukemias. They frequently have coagulation disorders with hemorrhage and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). There are diagnostic chromosomal t(15q+;17q-) translocations, which cause a fusion of the retinoic acid receptor-α region on chromosome 17 to a region in chromosome 15 (PML-RARα) and seem to account for a differentiation blockage of the myeloid lineage. Differentiation can be induced by administration of all-trans retinoic acid, with complete remission of disease in 70% to 85% of patients.

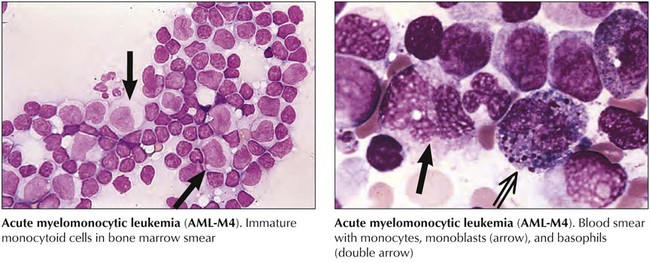

Acute myelomonocytic leukemia (AML-M4) is characterized by cells differentiating toward granulocytes and monocytes. Atypical blasts in the bone marrow (>30%) include myeloblasts, monoblasts, and promonocytes, the latter staining positive for (fluoride inhibitable) nonspecific esterase enzyme activity. There may be abnormal eosinophils with the appearance of monoblasts and eosinophil crystals in the cytoplasm, which may carry CD2+ T-cell markers (M4EO subtype). Clinical features include extramedullary disease with multiple organ involvement including the skin and the central nervous system (CNS). Pronounced hepatosplenomegaly and blood cell counts of 30,000 to 100,000 cells/mL are common. Karyotypic changes on chromosome 16 (inversions and translocations) may be found. The response rate to chemotherapy is 65% or greater. Acute monoblastic leukemia (AML-M5) is characterized by more than 80% cells of the monocytic series with positive cytoplasmic α-naphthyl acetate esterase reaction. It may occur in young age groups and is associated with a poor prognosis.

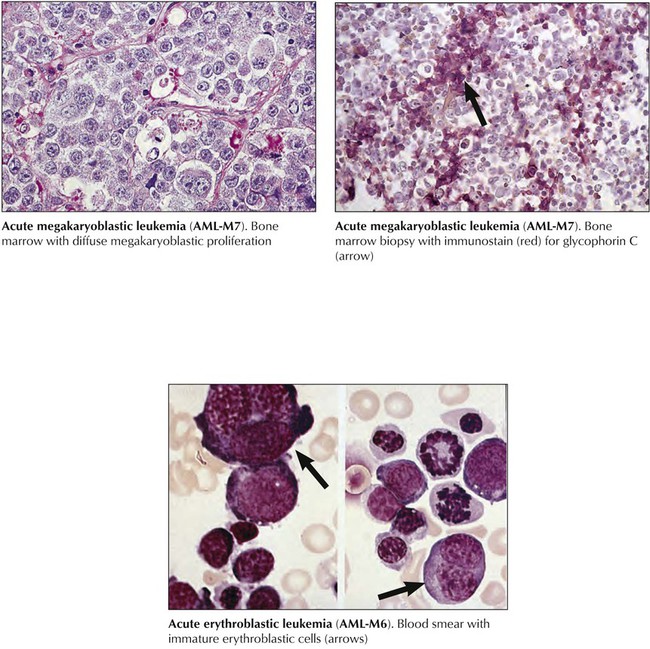

Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AML-M7) (acute myelofibrosis or malignant myelosclerosis), follows OMF or CML in up to half of patients. Megakaryoblasts (>30% of cells) are undifferentiated round cells reacting positively with antibodies against platelet glycoproteins or factor VIII–related antigens. WBC counts are usually 5,000 cells/mL or less. Secondary AML-M7 shows prominent hepatosplenomegaly. Advanced marrow fibrosis causes marrow aspirates to be inadequate for diagnosis (“dry tap”). Response to chemotherapy is usually poor. Acute erythroleukemia (AML-M6) is characterized by more than 50% abnormal erythroblasts with mixed proportions (30%) of myeloid and monocytic precursors. Peripheral blood smears show abnormal erythrocytes with prominent basophilic granules but rarely atypical blasts. Patients with acute erythroleukemia are usually older than 50 years and have anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, and occasionally rheumatic symptoms, polyclonal gammopathy, and Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia.

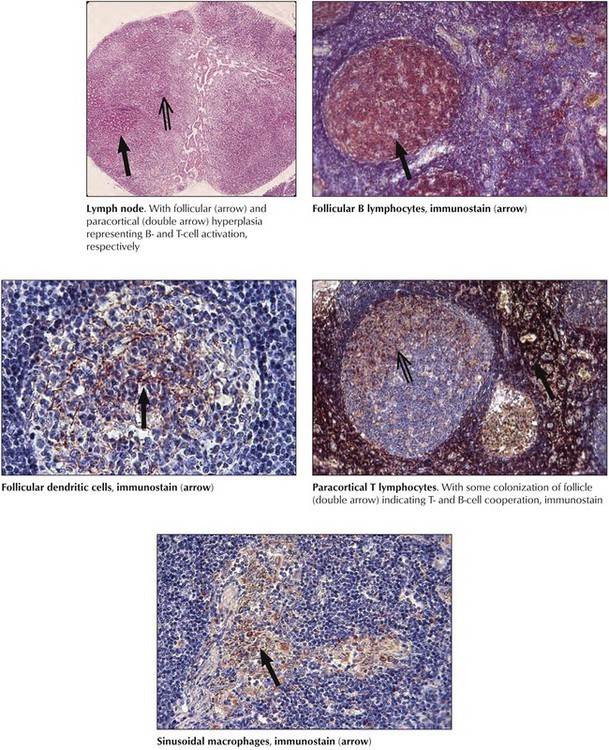

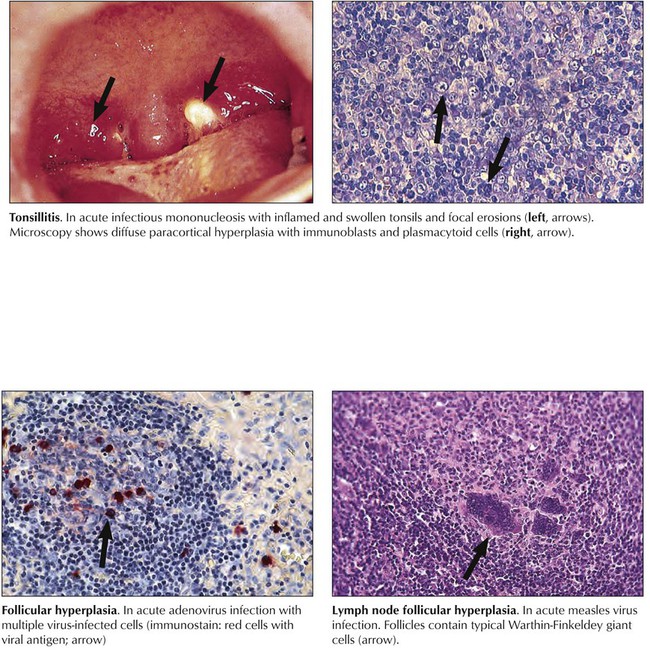

After preferred homing of cells in secondary lymphatic tissues and the subdivision of these tissues into functional T- and B-cell units, hyperplasia or aplasia in these units reflects T- or B-cell activities. Functional stimulation of the B-cell system leads to follicular hyperplasia, with prominent plasmacytosis in later stages. Stimulation of the T-cell system leads to paracortical hyperplasia and activation of phagocytosis to sinus histiocytosis or diffuse reticulohistiocytosis. Under physiologic conditions of stimulation by compound antigens, these units react together. Loss of reactivity (e.g., hypoplasia or atrophy) of one of these units indicates deficiency. Hyperplastic changes indicating functional activation of lymphatic tissues are found in various viral infections and are most pronounced in infections by lymphotropic viruses (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus types 6 and 7, cytomegalovirus). They cause clinical disorders such as infectious mononucleosis.

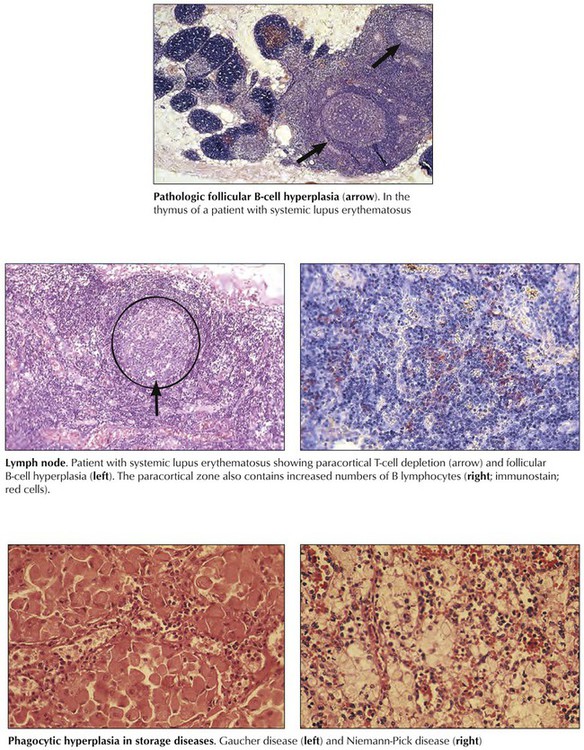

Pathologic aberrations from “physiologic” lymphatic hyperplasia are found in autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis) and are characterized by B-cell hyperactivity combined with selective T-cell deficiency. Typical lymph node changes consist of prominent follicular hyperplasia and plasmacytosis with paracortical lymphoid depletion. Regressive changes appear and may include degenerating and fibrotic germinal centers (burnt-out follicles), atrophy and fibrosis, or postcapillary venules and paracortical zones. Plasmacytosis increases. In some systemic autoimmune diseases, such as lupus erythematosus, the thymus shows an unusual B-cell hyperplastic reaction with follicular hyperplasia, germinal center formation, and plasmacytosis. Excessive and pathologic reactions in lymphatic tissues affect the phagocytic system, as occurs in storage diseases (thesauropathies, thesaurismoses), such as Niemann-Pick disease and Gaucher disease.

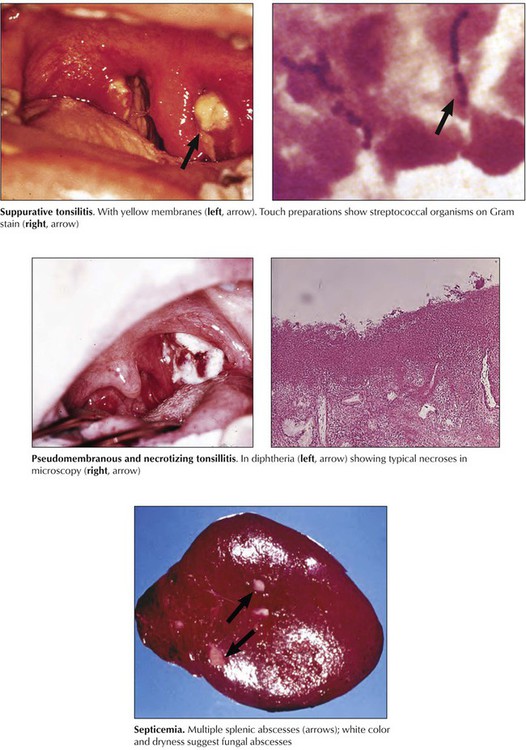

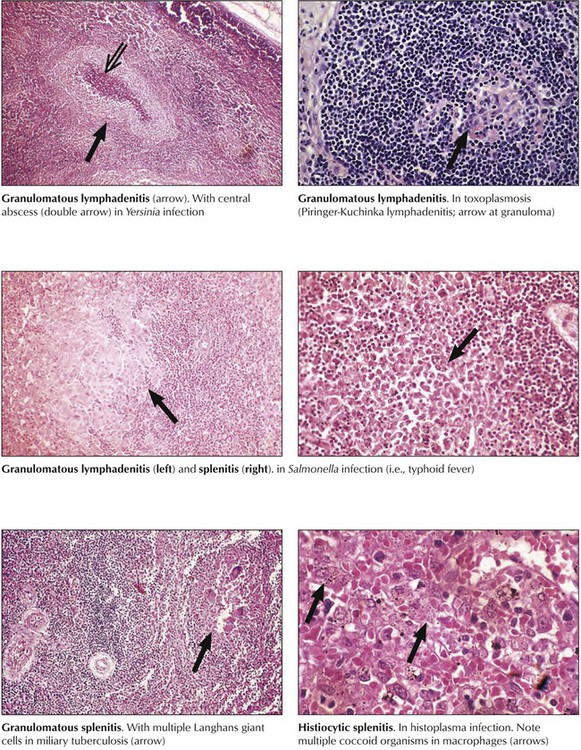

Bacterial infections (excluding organisms with intracellular replication) commonly cause suppurative inflammation; depending on their toxin production, they may cause necrosis, abscess formation, or hemorrhage. These are usually secondary infections after puriform infections in their lymphatic drainage area or septicemia. Lymphadenitis or splenitis with abscess formation is also common in acute fungal infections such as those caused by Candida species. If superficial (mucosal) lymphoid organs are involved, localized erosions, ulcerations, and pseudomembranous inflammation may result, as is typically observed in streptococcal and diphtheric tonsillitis or in Peyer patches with salmonella infections (typhoid fever).

Infections with intracellular organisms persist for a long period, stimulating the T-cell immune system and phagocytosis. Consequently, granulomatous inflammation arises in lymphatic tissues just as it would in other organs. Depending on the toxicity of the etiologic agent, necrosis and abscess formation may occur together. Granulomatous lymphadenitis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Salmonella species, or fungi of the Histoplasma genus is an example of such a reaction. Combinations of follicular granulomas and centrally located abscesses are found in such diverse infections as Yersinia lymphadenitis, lymphogranuloma venereum, tularemia, and catscratch disease. Some toxic fungal infections, such as histoplasmosis and mucormycosis, may cause similarly combined necrotic and granulomatous reactions.

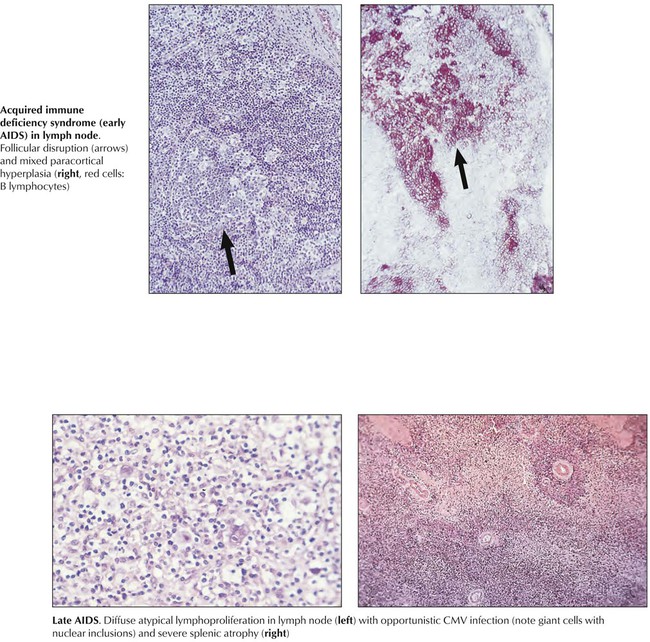

Viral infections may cause hyperplastic reactions in lymphatic tissues. Specific viral infections can be identified only by characteristic cytopathic effects (e.g., Warthin-Finkeldey cells in measles virus infection or cytomegalic inclusion disease in cytomegalovirus infection) or by immunologic and molecular techniques for viral antigens and nucleic acids. Except for the lymphotropic viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus, where such techniques may occasionally be helpful, viral infections are proven by observing their characteristic diseases in nonlymphatic organs and by serologic testing or viral isolation. Lymphotropic viruses cause a prominent paracortical T-zone hyperplasia with release of stimulated T and B cells into the bloodstream (mononucleosis cells, plasmablastoid B cells). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection causes rapid loss of cells from the paracortical T-cell zone, structural disruption of cortical follicles, and reactive polyclonal B-cell proliferation.

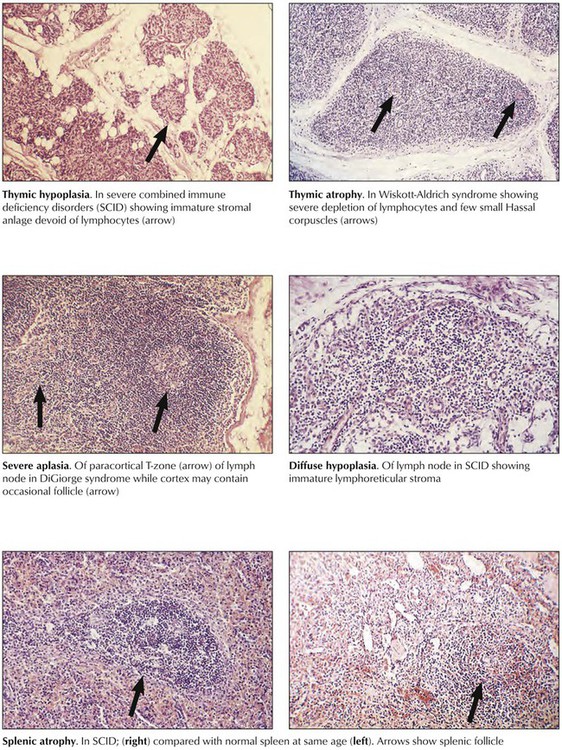

Immune deficiency disorders (IDDs) may be inherited or acquired. Either may affect the B- or T-cell systems or both, with thymic atrophy, paracortical and cortical atrophy of lymph nodes, or follicular atrophy of the spleen and other lymphoid tissues. Reticular dysgenesis (DeVaal-Seynhaeve syndrome), the most extensive form of inherited IDD, affects the T- and B-cell systems and hematopoiesis. Other classic examples, all incompatible with life, are DiGeorge syndrome of the T-cell system and of the parathyroid glands, Bruton disease of the B-cell system, and severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) of T and B cells.

Acquired immune deficiency disorders are caused by toxic drugs (chemotherapeutics, steroids, analgesics, and others), ionizing radiation, endocrine and metabolic disturbances, chronic alcoholism, and viral infections such as congenital rubella and HIV, which is characterized by a combination of T-cell deficiency and polyclonal B-cell proliferation. The diagnosis and classification of IDDs follows detailed immunologic testing. Pathologic studies with immunologic T- and B-cell quantification show hypoplasia or atrophy of the T-cell system (i.e., thymus and paracortical area of lymph nodes, periarteriolar sheath of spleen), hypoplasia or atrophy of the B-cell system (i.e., lymph node and splenic follicles, plasma cell maturation), or combinations of these features. Clinical consequences of IDDs include opportunistic infections and neoplasia (e.g., MLs).

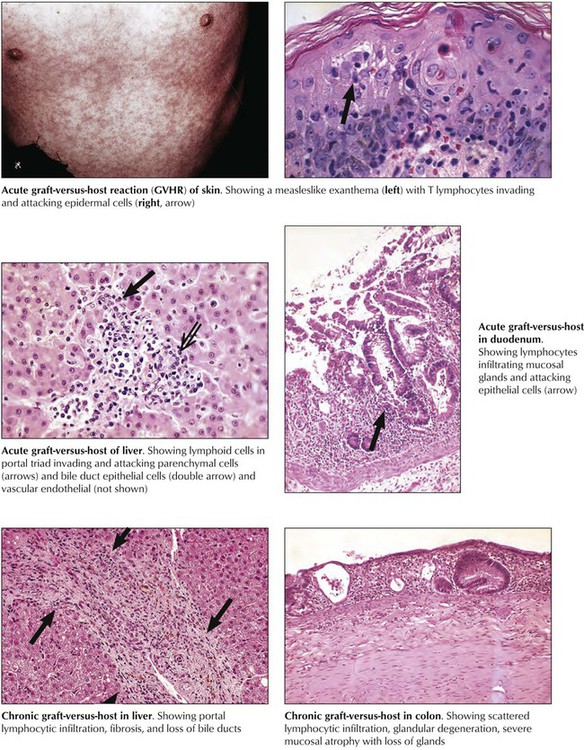

Graft-versus-host reaction (GVHR) is the “rejection” of the recipient (host) by a transplant (graft). It may occur whenever genetically foreign immunocompetent cells are transplanted into an immunodeficient recipient, especially in bone marrow allotransplantation. It also may occur in patients with leukemia or other IDDs who receive multiple blood transfusions. Transfused immunocompetent T lymphocytes recognize and destroy such allogeneic host cells as epidermal cells, hepatocytes, bile duct epithelia, intestinal epithelial cells, and cells of hemolymphatic tissues. Microscopically, a typical acute GVHR shows a T-cell immune reaction in the skin, the liver, and the upper intestines combined with growth inhibition and atrophy of hemolymphatic tissues. Severe acute GVHR has a high mortality secondary to severe ulcerating enteritis with superinfection, diarrhea, and fluid loss; severe hepatitis with hepatocellular necroses; or systemic viral disease and bacterial septicemia.

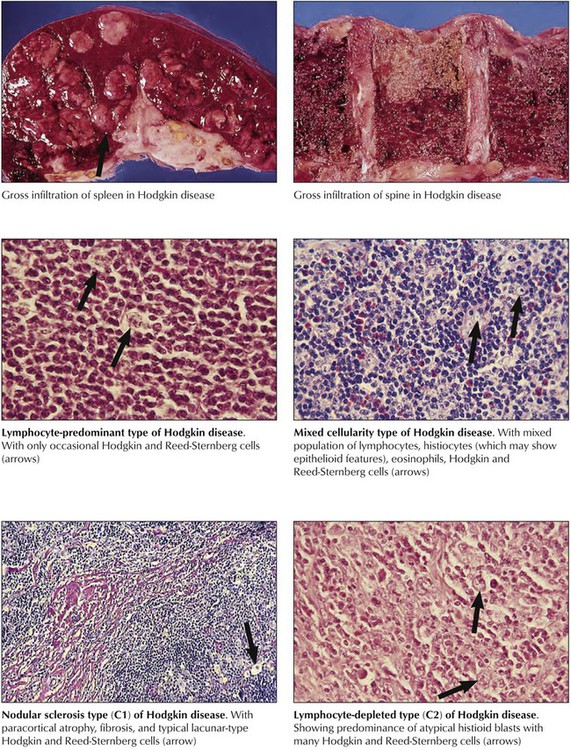

Hodgkin disease is characterized histologically by mixed proliferations of lymphoid cells with various numbers of histiocytes, eosinophils, and the diagnostic Hodgkin cells or Reed-Sternberg cells. Lymph nodes may show focal or diffuse involvement with effacement of the architecture and invasion beyond their capsule. HD cells are mononuclear histiocytoid blasts with vesicular nuclei and large prominent nucleoli. Reed-Sternberg cells are essentially similar but binucleated blasts. HD are classified into 4 major groups according to their overall cell composition: lymphocyte-predominant type, mixed-cellularity type, nodular-sclerosing type, and lymphocyte-depleted type. The most frequently affected lymph nodes are in the mediastinum (59%), the neck (55-58%), the axillae (13-14%), and the lung hilus (11-12%). Multimodal radiation therapy and chemotherapy can result in stage-dependent disease-free survival of up to 94% at 10 years.

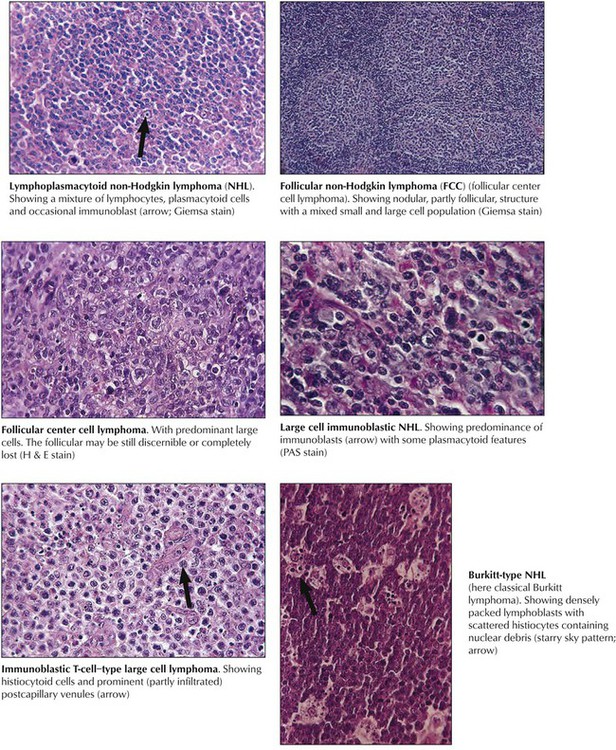

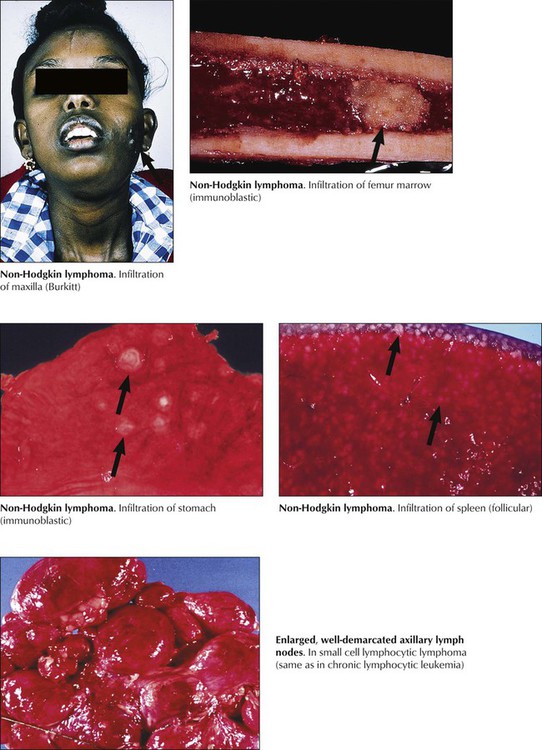

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas are a diverse group of monoclonal T- or B-cell proliferative diseases recently classified according to the Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification, shown in Table 10-4, which categorizes them based on cytology, histologic growth pattern, immunologic phenotype, and cytogenetic markers and includes consideration of clinical course and prognosis. Immunologically, there are B-cell lymphomas, T-cell lymphomas, T-cell–rich B-cell lymphomas, B-cell–rich T-cell lymphomas, and natural killer (NK) cell lymphomas. The etiology of most NHLs is unknown. Some are related to viral infection; Epstein-Barr virus is implicated in Burkitt and Burkitt-type lymphoma, and human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV-1) is implicated in adult T-cell leukemia (ATL). Many NHLs show genetic mutations with unusual oncogene activation (e.g., c-myc, BCL-2, BCL-1, BCL-6, PAX-5, NPM/ALK) or inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (p53, p16).

Patients with NHL present with persistent indolent lymphadenopathy with or without splenic enlargement and B-symptoms (night sweats, fever, weight loss). Internal and extranodal lymphomas cause symptoms only by compression or infiltration of adjacent organs (e.g., abdominal discomfort, uncharacteristic GI problems). Hypersplenism or direct invasion of the bone marrow may be followed by anemia, thrombocytopenia, and pancytopenia. Treatment of NHL is adjusted according to its histologic classification and clinical stage. Follicular lymphomas and small-cell lymphomas are usually less aggressive and have a better prognosis than large-cell and diffuse lymphomas. In certain lymphomas, however, relapses have been described after periods as long as 15 years.

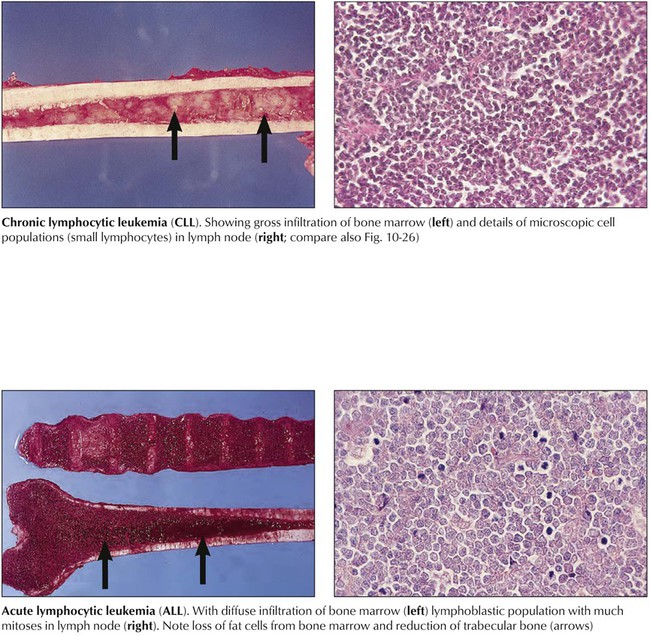

Lymphocytic leukemias are characterized by hematogenous circulation of malignant cells and lymphomatous infiltration of bone marrow, lymphatic organs, or extralymphatic sites. CLL, in approximately 90% of cases a B-cell malignancy, is the most common form of leukemia. Immunodeficiency and autoimmune reactions (autoimmune hemolytic anemia) may accompany CLL, rendering the patient susceptible to infections. The disease course is slowly progressive but rapid when chemotherapy becomes necessary. Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL; cytologic subtypes L1-L3 according to cell size) is preferentially a childhood leukemia. Approximately 80% of cases of childhood ALL consist of monoclonal B-precursor cells, and approximately 15% consist of cells from the T-cell lineage. Clinical features are anemia (pallor, fatigue), thrombocytopenia (hemorrhage), and mature leukocytopenia (infections). Combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy have resulted in long-term disease-free survival of 70% to 80% of children.

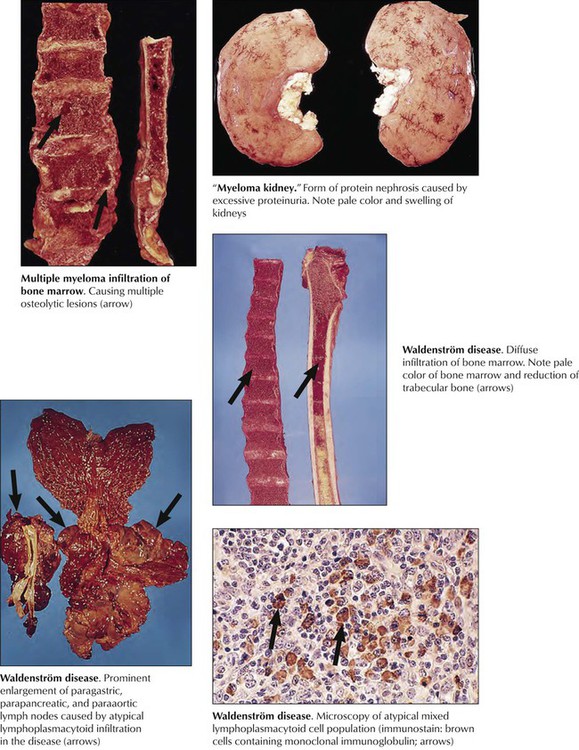

Multiple myeloma is a neoplastic clonal proliferation of plasma cells (plasmacytoma) usually at multiple sites in the bone marrow. It frequently is accompanied by the production of unusual immunoglobulin components (gammopathy, monoclonal M protein in serum, and Bence Jones protein in urine). Clinical features include bone pain, anemia, bleeding, hypercalcemia, hyperglobulinemia (myeloma kidney), and susceptibility to infection. Systemic amyloidosis develops in later stages of the disease. With treatment, the life expectancy is approximately 2.5 to 3 years. Waldenström disease (WD) is another form of mature B-cell neoplasia with respective lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the bone marrow and immunoglobulin (Ig) M macroglobulinemia. Other frequently involved sites are lymph nodes, spleen, GI tract, lungs, and skin. Clinical features are hyperviscosity, cryoglobulinemia, bleeding, renal disease, peripheral neuropathy, and amyloidosis. The median survival of patients with WD is 5 years.