Chapter 3 HEARTBURN, ACID REGURGITATION AND BARRETT’S OESOPHAGUS

DEFINITIONS AND SPECTRUM

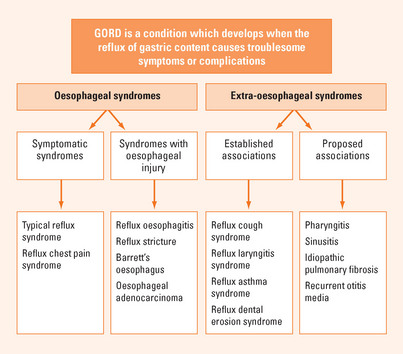

Heartburn is defined as a burning sensation in the retrosternal area and regurgitation as the perception of flow of refluxed gastric content into the mouth or hypopharynx. These are the cardinal symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux. Reflux is a physiological event but excessive reflux exposes the patient to the risk of physical complications or symptoms that impair quality of life. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is defined as a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms or complications. Thus, in the absence of physical complications the definition depends on the impact of symptoms on an individual. Frequently, significant impairment of well-being (quality of life) occurs when symptoms occur on two or more days a week. GORD can be divided into oesophageal syndromes and extra-oesophageal syndromes (Figure 3.1). The former includes symptomatic syndromes of typical reflux symptoms and reflux induced chest pain and syndromes associated with oesophageal injury including oesophagitis (erosive GORD), strictures, Barrett’s oesophagus and the small risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Extra-oesophageal reflux syndromes include the established associations with cough, laryngitis and asthma as well as other putative associations.

EPIDEMIOLOGY, RISK FACTORS AND NATURAL HISTORY

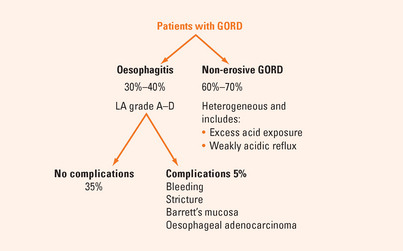

Most patients with GORD have normal oesophageal mucosa at endoscopy (Figure 3.2). Only about one-third of patients with reflux disease have reflux oesophagitis confirmed by endoscopically visible mucosal breaks (erosions or ulceration).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Hiatal hernia is common in reflux disease. Hiatal hernia increases the likelihood that reflux will occur by impairing LOS function. However, the presence of a hiatal hernia does not necessarily mean that reflux disease is present.

DIAGNOSIS

Symptom recognition and assessment

Atypical symptoms include chest pain, which may mimic cardiac pain, and symptoms associated with extra-oesophageal manifestations of GORD including cough, sore throat, hoarseness and wheeze. GORD should be considered in patients who present with no other apparent cause for these symptoms although most patients with reflux-induced extra-oesophageal symptoms will also have typical GORD symptoms.

INVESTIGATIONS

The role of endoscopy

It is inappropriate to investigate every patient with suspected GORD. Patients who have mild, typical reflux symptoms and no alarm symptoms may be given a trial of therapy without investigation.

Endoscopy is warranted if the diagnosis is unclear, because symptoms are either non-specific or atypical for GORD or are ‘mixed’ with upper gut symptoms, such as epigastric pain (Table 3.1). Endoscopy should also be undertaken for symptoms that persist or are refractory to treatment, when complications are suspected or there are alarm symptoms present (weight loss, dysphagia, odynophagia, bleeding or anaemia).

Ancillary tests

24-hour ambulatory oesophageal pH monitoring

Only a minority of patients need ancillary testing. A pH study tests whether symptoms are temporally related to the occurrence of reflux. Measurement of the amount of reflux that occurs is of lesser diagnostic value. pH monitoring is also useful in patients in whom the diagnosis is unclear after endoscopy and a therapeutic PPI trial. It is used particularly in patients with suspected extra-oesophageal manifestations of GORD. It also has a role in assessing the adequacy of acid suppression in patients taking PPIs with presumed GORD who continue to have symptoms on therapy.

MANAGEMENT OF GORD

Medical therapy

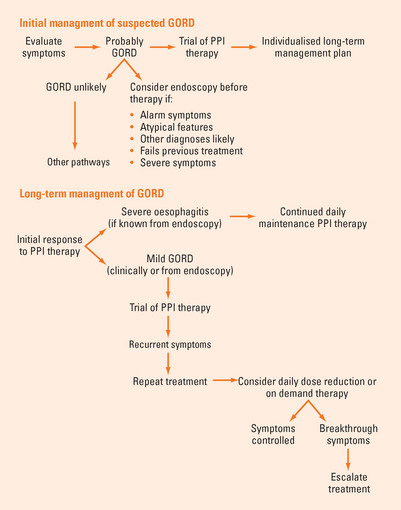

PPIs are the most effective therapy for GORD, providing rapid and reliable symptom resolution and healing of oesophagitis in most patients (80% after 8 weeks). Management involves a first phase of diagnosis, assessment of severity and initial trial of once-daily PPI therapy, usually given before breakfast, for 4–8 weeks (Figure 3.3). Patients with prominent evening or nocturnal symptoms may be dosed before the evening meal. A positive initial response to PPI therapy supports the clinical diagnosis, relieves symptoms, reassures the patient and heals oesophagitis if present. While the majority of patients with GORD will achieve good control of symptoms, a substantial minority will not. These patients are more likely to have non-erosive GORD with less acid reflux demonstrable and are less responsive to acid suppression.

FIGURE 3.3 Management pathways for GORD.

GORD = gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; PPI = proton pump inhibitor.

The second or maintenance phase involves tailoring an individualised long-term plan using the lowest dose and frequency of drug possible. The aim is to control symptoms and minimise relapses, reduce the risk of complications of the disease or of therapy and to minimise costs. Patients with longstanding, severe symptoms or a higher grade of oesophagitis need continuous PPI therapy, as relapse is inevitable if treatment is withdrawn. A few patients need twice-daily dosing. Milder disease is treated with less intense therapy. A trial of treatment cessation is warranted in patients with short-term symptoms as not all patients relapse. An attempt can be made to ‘step down’ to a lower PPI dose or to an H2-receptor antagonist (H2-RA). Intermittent, self-directed (‘on demand’) therapy is effective for some patients with less frequent symptoms. Patient-directed use of antacids, antacid/alginate combinations or ‘over the counter’ H2-RAs may be helpful for the relief of mild and occasional reflux symptoms but are adjunctive treatment only for significant GORD. Prokinetic agents have little role in management.

Endoscopic antireflux therapy

Endoscopic procedures have been developed as alternatives to laparoscopic fundoplication. Adequate comparative short-and long-term efficacy data are lacking and safety issues are unresolved. Although these techniques are being used, at present such techniques should be considered experimental and their use confined to clinical trials in major centres.

Barrett’s oesophagus

Definitions of Barrett’s oesophagus vary, but the core component is the presence of metaplastic columnar epithelium from the gastro-oesophageal junction and extending proximally. Specialised intestinal metaplasia (SIM) is often identified in this metaplastic epithelium and it is the presence of SIM that confers the risk of progression to dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. For this reason the presence of oesophageal SIM identified by histological examination of biopsy specimens is considered a prerequisite for the diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus by some, whereas others prefer to describe Barrett’s oesophagus on endoscopic appearances and then specify the presence or absence of SIM after biopsy results are available. The endoscopic description of Barrett’s oesophagus should include a standardised measure of extent.

When Barrett’s oesophagus is found or suspected in the presence of oesophagitis, epithelial atypia or dysplasia may be misdiagnosed. In this case the examination needs to be repeated after mucosal healing with PPIs. Surveillance of Barrett’s oesophagus after initial diagnosis aims to identify patients who progress to high-grade dysplasia or early adenocarcinoma so that appropriate intervention can be provided to improve survival. The optimal surveillance interval is not defined. Generally, 2–3-yearly biopsies are recommended.

SUMMARY

Heartburn is defined as a burning sensation in the retrosternal area. Regurgitation is the perception of flow of reflux gastric content into the mouth or hypopharynx. GORD is defined as a condition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms or complications. Risk factors for GORD include hiatal hernia, obesity and increasing age. Most GORD is non-erosive (endoscopy-negative reflux disease). About one-third of patients have oesophagitis (erosions or mucosal breaks). GORD is associated with excessive oesophageal acid exposure. Some patients have symptoms triggered by weakly acidic reflux episodes. GORD encompasses oesophageal syndromes and extra-oesophageal syndromes. The diagnosis of GORD is mostly symptom based. Typical symptoms are heartburn and acid regurgitation. Other symptoms include excessive belching, odynophagia and waterbrash. Atypical symptoms include chest pain, cough and sore throat. Dysphagia occurs with GORD, but in conjunction with weight loss, anaemia or bleeding is an indication for endoscopy to exclude strictures or malignancy. Notably, GORD symptoms can overlap with peptic ulcer disease and functional (non-ulcer) dyspepsia. In some patients with GORD, epigastric pain is the major symptom. Many patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) also complain of reflux symptoms, suggesting that both conditions may be part of the spectrum of a broader gastrointestinal disorder. Assessment of the duration, frequency and severity of symptoms and the impact of symptoms on quality of life allows grading of GORD severity and guides therapy. A positive response to a therapeutic trial of PPI therapy supports the diagnosis of GORD, although both false positives and false negatives occur with a PPI trial. Endoscopy is warranted if the diagnosis is unclear or when symptoms persist or are refractory, or if there are alarm symptoms. The goals of management are to relieve symptoms, reduce risk and restore quality of life. PPIs are the most effective pharmacotherapy for GORD providing rapid and reliable symptom resolution and healing of oesophagitis in most patients. Management involves an initial trial of a PPI and a tailored long-term plan using the lowest dose and frequency of drug. Antireflux surgery is an option for a selected minority or those who prefer not to take acid suppression therapy. Weight loss in obese patients may improve symptoms of GORD and should be advised. Barrett’s oesophagus is a premalignant condition conferring an increased risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. However, there is controversy regarding optimal screening, surveillance and treatment for this condition currently.

DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190-200.

Katelaris PH. An evaluation of current GERD therapy: a summary and comparison of effectiveness, adverse effects and costs of drugs, surgery and endoscopic therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18(Suppl):39-45.

Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2006;387:2086-2100.

Sharma P, McQuaid K, Dent J, et al. A critical review of the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus: the AGA Chicago Workshop. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:310-330.

Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et alGlobal Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920.

van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Bonis PA, et al. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2006. CD002095