Chapter 23

Heart Failure Evaluation and Long-Term Management

Arunima Misra, MD, FACC, Kumudha Ramasubbu, MD, FACC, Shawn T. Ragbir, MD, Glenn N. Levine, MD, FACC, FAHA and Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA

This chapter deals specifically with the evaluation and long-term management of patients with heart failure caused by depressed ejection fraction. The management of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (diastolic dysfunction) is discussed in Chapter 24. The management of patients with acute decompensated heart failure is discussed in Chapter 22. Specific discussions of the evaluation and management of myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and restrictive/infiltrative cardiomyopathy, as well as consideration with cardiac transplantation, are discussed in other dedicated chapters in this section of the book. The roles of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with heart failure are discussed in this chapter, as well as in the chapters on pacemakers (Chapter 37) and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (Chapter 38).

1. What are the most common causes of heart failure?

2. What elements should the initial assessment of the patient with heart failure include?

Initial assessment of the patient with heart failure should include:

Evaluation of heart failure symptoms and functional capacity (dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea [PND], fatigue, and lower extremity edema)

Evaluation of heart failure symptoms and functional capacity (dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea [PND], fatigue, and lower extremity edema)

Evaluation for the presence of diabetes; hypertension; smoking; prior cardiac disease; family history of cardiac disease; history of heart murmur, congenital heart disease, or rheumatic fever; sleep disturbances (obstructive sleep apnea [OSA]); thyroid disease history; exposure to infectious agents; exposure to cardiotoxins; mediastinal irradiation; and past or current use of alcohol and illicit drugs

Evaluation for the presence of diabetes; hypertension; smoking; prior cardiac disease; family history of cardiac disease; history of heart murmur, congenital heart disease, or rheumatic fever; sleep disturbances (obstructive sleep apnea [OSA]); thyroid disease history; exposure to infectious agents; exposure to cardiotoxins; mediastinal irradiation; and past or current use of alcohol and illicit drugs

Physical examination, including heart rate and rhythm; blood pressure and orthostatic blood pressure changes; measurements of weight, height, and body mass index; overall volume status; jugular venous distension; carotid upstroke and presence or absence of bruits; lung examination for rales or effusions; cardiac examination for systolic or diastolic murmurs; displaced point of maximal impulse (PMI); presence of left ventricular heave; intensity of S2; presence of S3 or S4; liver size; presence of ascites; presence of renal bruits; presence of abdominal aortic aneurysm; peripheral edema; peripheral pulses; and checking whether the extremities are cold and clammy

Physical examination, including heart rate and rhythm; blood pressure and orthostatic blood pressure changes; measurements of weight, height, and body mass index; overall volume status; jugular venous distension; carotid upstroke and presence or absence of bruits; lung examination for rales or effusions; cardiac examination for systolic or diastolic murmurs; displaced point of maximal impulse (PMI); presence of left ventricular heave; intensity of S2; presence of S3 or S4; liver size; presence of ascites; presence of renal bruits; presence of abdominal aortic aneurysm; peripheral edema; peripheral pulses; and checking whether the extremities are cold and clammy

Laboratory tests, including complete blood cell count (CBC), creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum electrolytes, natriuretic peptide (BNP or NT-proBNP), fasting blood glucose, lipid profile, liver function tests, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and urine analysis; and screening for hemochromatosis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), pheochromocytoma, amyloidosis, or rheumatologic diseases reasonable in selected patients, particularly if there is clinical suspicion for testing

Laboratory tests, including complete blood cell count (CBC), creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum electrolytes, natriuretic peptide (BNP or NT-proBNP), fasting blood glucose, lipid profile, liver function tests, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and urine analysis; and screening for hemochromatosis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), pheochromocytoma, amyloidosis, or rheumatologic diseases reasonable in selected patients, particularly if there is clinical suspicion for testing

Twelve-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), assessing for rhythm, conduction abnormalities, QRS voltage and duration, QT duration, chamber enlargement, presence of ST/T changes, and Q waves

Twelve-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), assessing for rhythm, conduction abnormalities, QRS voltage and duration, QT duration, chamber enlargement, presence of ST/T changes, and Q waves

Transthoracic echocardiogram to asses for left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) function: wall motion; chamber sizes; filling pressures; morphology of the valves; presence of ventricular hypertrophy; and diastolic parameters

Transthoracic echocardiogram to asses for left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) function: wall motion; chamber sizes; filling pressures; morphology of the valves; presence of ventricular hypertrophy; and diastolic parameters

Consideration of ischemia workup; depending on patient’s age, history, symptoms, and ECG, this may be no workup, stress testing, or cardiac catheterization.

Consideration of ischemia workup; depending on patient’s age, history, symptoms, and ECG, this may be no workup, stress testing, or cardiac catheterization.

Endomyocardial biopsy is not part of routine workup but can be considered in highly specific circumstances (see later).

Endomyocardial biopsy is not part of routine workup but can be considered in highly specific circumstances (see later).

Consider cardiac MRI if infiltrative causes, such as cardiac sarcoidosis or amyloidosis, are suspected.

Consider cardiac MRI if infiltrative causes, such as cardiac sarcoidosis or amyloidosis, are suspected.

3. How are heart failure symptoms classified?

Class I: No limitation; ordinary physical activity does not cause excess fatigue, shortness of breath, or palpitations.

Class I: No limitation; ordinary physical activity does not cause excess fatigue, shortness of breath, or palpitations.

Class II: Slight limitation of physical activity; ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, shortness of breath, palpitations, or angina.

Class II: Slight limitation of physical activity; ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, shortness of breath, palpitations, or angina.

Class III: Marked limitation of physical activity; ordinary activity will lead to symptoms.

Class III: Marked limitation of physical activity; ordinary activity will lead to symptoms.

Class IV: Inability to carry on any physical activity without discomfort; symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF) are present even at rest; increased discomfort is experienced with any physical activity.

Class IV: Inability to carry on any physical activity without discomfort; symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF) are present even at rest; increased discomfort is experienced with any physical activity.

4. What is the stage system for classifying heart failure?

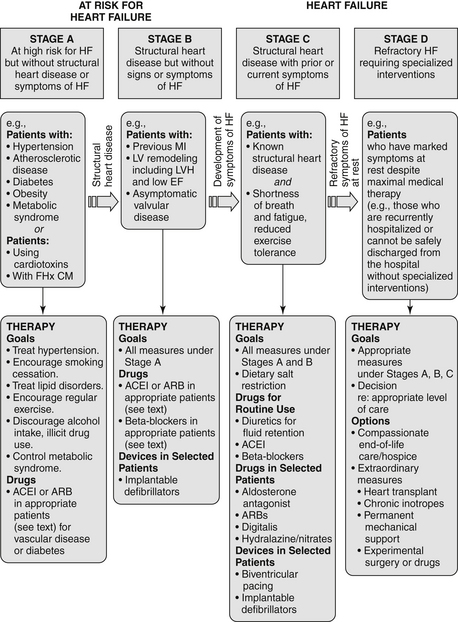

In 2001, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) introduced a system to categorize the stages of heart failure. This system is somewhat different in focus than the previous NYHA classification system and was intended, in part, to emphasize the prevention of the development of symptomatic heart failure. In addition, the 2009 update on the 2005 Heart Failure Guidelines suggest appropriate therapy for each stage (Figure 23-1).

Figure 23-1 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Stages in the Development of Heart Failure/Recommended Therapy by Stage. (From Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, et al: ACC/AHA 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults : a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: Developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, Circulation 119:1977-2016, 2009; originally published online March 26, 2009.) ACEI, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; EF, ejection fraction; FHx CM, family history of cardiomyopathy; HF, heart failure; LV, left ventricle; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MI, myocardial infarction.

Stage A: Patient is at high risk for developing heart failure but is without structural heart disease or symptoms of heart failure. Includes patients with hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), obesity, diabetes, history of drug or alcohol abuse, history of rheumatic fever, family history of cardiomyopathy, or treatment with cardiotoxins

Stage A: Patient is at high risk for developing heart failure but is without structural heart disease or symptoms of heart failure. Includes patients with hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), obesity, diabetes, history of drug or alcohol abuse, history of rheumatic fever, family history of cardiomyopathy, or treatment with cardiotoxins

Stage B: Patient with structural heart disease but is without signs or symptoms of heart failure. Includes patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI), LV remodeling (including left ventricular hypertrophy [LVH] or low ejection fraction), or asymptomatic valvular disease

Stage B: Patient with structural heart disease but is without signs or symptoms of heart failure. Includes patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI), LV remodeling (including left ventricular hypertrophy [LVH] or low ejection fraction), or asymptomatic valvular disease

Stage C: Patient with structural heart disease and with prior or current symptoms of heart failure

Stage C: Patient with structural heart disease and with prior or current symptoms of heart failure

Stage D: Patient with refractory heart failure requiring specialized interventions

Stage D: Patient with refractory heart failure requiring specialized interventions

5. Which patients with heart failure should be considered for endomyocardial biopsy (EMB)?

In 2007, the ACC/AHA/European College of Cardiology (ACC/AHA/ECC) issued a scientific statement on the role of EMB. Most patients who are seen for heart failure should not be referred for EMB. Biopsy results are often nonspecific or unrevealing, and in most cases there is no specific therapy based on biopsy results that have been shown to improve prognosis. However, in certain clinical scenarios, EMB should be performed (class I recommendation) or can be considered and is considered reasonable (class IIa recommendation). As given in that document, these scenarios include the following:

New-onset heart failure of less than 2 weeks duration associated with a normal-sized or dilated left ventricle and hemodynamic compromise (class I; level of evidence B)

New-onset heart failure of less than 2 weeks duration associated with a normal-sized or dilated left ventricle and hemodynamic compromise (class I; level of evidence B)

New-onset heart failure of 2 weeks to 3 months duration associated with a dilated left ventricle and new ventricular arrhythmias, second- or third-degree heart block, or failure to respond to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks (class I; level of evidence B)

New-onset heart failure of 2 weeks to 3 months duration associated with a dilated left ventricle and new ventricular arrhythmias, second- or third-degree heart block, or failure to respond to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks (class I; level of evidence B)

Heart failure of more than 3 months duration associated with a dilated left ventricle and new ventricular arrhythmias, second- or third-degree heart block, or failure to respond to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks (class IIa; level of evidence C)

Heart failure of more than 3 months duration associated with a dilated left ventricle and new ventricular arrhythmias, second- or third-degree heart block, or failure to respond to usual care within 1 to 2 weeks (class IIa; level of evidence C)

Heart failure associated with a dilated cardiomyopathy of any duration associated with suspected allergic reaction or eosinophilia (class IIa; level of evidence C)

Heart failure associated with a dilated cardiomyopathy of any duration associated with suspected allergic reaction or eosinophilia (class IIa; level of evidence C)

Heart failure associated with suspected anthracycline cardiomyopathy (class Ia; level of evidence C)

Heart failure associated with suspected anthracycline cardiomyopathy (class Ia; level of evidence C)

Heart failure with unexplained restrictive cardiomyopathy (class IIa; level of evidence C)

Heart failure with unexplained restrictive cardiomyopathy (class IIa; level of evidence C)

6. What are the general treatments for patients with heart failure?

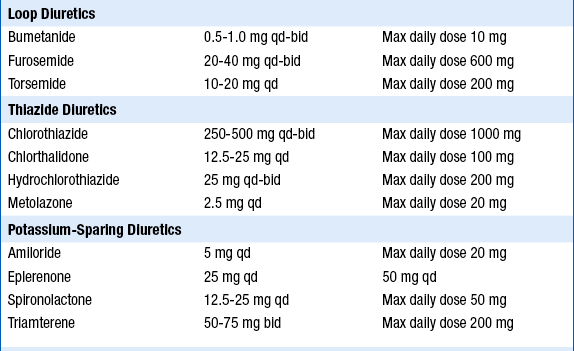

Diuretics are indicated for volume overload. Starting doses of furosemide are often 20 to 40 mg once or twice a day, but higher doses will be required in patients with significant renal dysfunction. The dose should be uptitrated to a maximum of up to 600 mg daily in divided doses. Failure of therapy is often the result of inadequate diuretic dosing. Torsemide is more expensive than furosemide but has superior absorption and longer duration of action. Bumetanide is approximately 40 times more potent milligram-for-milligram than furosemide and can also be used in patients who are unresponsive or poorly responsive to furosemide. Synergistic diuretics that act on the distal portion of the tubule (thiazides such as metolazone, or potassium-sparing agents) are often added in those who fail to respond to high-dose loop diuretics alone. In addition, a new recommendation from 2009 Focused Update states that for hospitalized heart failure patients, if diuresis is inadequate to relieve congestion, higher doses of loop diuretics should be used, addition of second diuretic should be made or continuous infusion of a loop diuretic should be considered.

Diuretics are indicated for volume overload. Starting doses of furosemide are often 20 to 40 mg once or twice a day, but higher doses will be required in patients with significant renal dysfunction. The dose should be uptitrated to a maximum of up to 600 mg daily in divided doses. Failure of therapy is often the result of inadequate diuretic dosing. Torsemide is more expensive than furosemide but has superior absorption and longer duration of action. Bumetanide is approximately 40 times more potent milligram-for-milligram than furosemide and can also be used in patients who are unresponsive or poorly responsive to furosemide. Synergistic diuretics that act on the distal portion of the tubule (thiazides such as metolazone, or potassium-sparing agents) are often added in those who fail to respond to high-dose loop diuretics alone. In addition, a new recommendation from 2009 Focused Update states that for hospitalized heart failure patients, if diuresis is inadequate to relieve congestion, higher doses of loop diuretics should be used, addition of second diuretic should be made or continuous infusion of a loop diuretic should be considered.

Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system should be initiated. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are first-line agents in those with depressed ejection fraction because they have been convincingly shown to improve symptoms, decrease hospitalizations, and reduce mortality. Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are used in those who are ACE-inhibitor intolerant because of persistent cough. ARBs may also be considered in addition to ACE inhibitors in select patients (this latter decision is best left to a heart failure specialist). The aldosterone antagonists spironolactone or eplerenone can be considered as additional therapy in carefully selected patients with preserved renal function already on standard heart failure therapies.

Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system should be initiated. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are first-line agents in those with depressed ejection fraction because they have been convincingly shown to improve symptoms, decrease hospitalizations, and reduce mortality. Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are used in those who are ACE-inhibitor intolerant because of persistent cough. ARBs may also be considered in addition to ACE inhibitors in select patients (this latter decision is best left to a heart failure specialist). The aldosterone antagonists spironolactone or eplerenone can be considered as additional therapy in carefully selected patients with preserved renal function already on standard heart failure therapies.

Hydralazine and isosorbide are used in patients who are unable to tolerate both ACE inhibitors and ARBs because of renal failure. Hydralazine and isosorbide should be considered in addition to an ACE inhibitor or ARB in African Americans, and can be considered as an add-on therapy in others. They may be considered in patients who are ACE inhibitor and ARB intolerant.

Hydralazine and isosorbide are used in patients who are unable to tolerate both ACE inhibitors and ARBs because of renal failure. Hydralazine and isosorbide should be considered in addition to an ACE inhibitor or ARB in African Americans, and can be considered as an add-on therapy in others. They may be considered in patients who are ACE inhibitor and ARB intolerant.

The beta-adrenergic blocking agents (β-blockers) metoprolol succinate (Toprol XL), carvedilol (Coreg), and bisoprolol have been shown to decrease mortality in appropriately selected patients. These agents should be initiated in euvolemic patients on stable background heart failure therapy, including ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

The beta-adrenergic blocking agents (β-blockers) metoprolol succinate (Toprol XL), carvedilol (Coreg), and bisoprolol have been shown to decrease mortality in appropriately selected patients. These agents should be initiated in euvolemic patients on stable background heart failure therapy, including ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are considered for primary prevention in patients whose ejection fractions remain less than 30% to 35% despite optimal medical therapy, and who have a good-quality life expectancy of at least 1 year.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are considered for primary prevention in patients whose ejection fractions remain less than 30% to 35% despite optimal medical therapy, and who have a good-quality life expectancy of at least 1 year.

Biventricular pacing for resynchronization therapy should be considered. According to the 2009 American College of Cardiology Foundation/AHA (ACCF/AHA) guidelines, biventricular pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) should be considered for patients in sinus rhythm with NYHA class III-IV symptoms, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 35%, and QRS greater than 120 ms. Consultation with an electrophysiologist is recommended.

Biventricular pacing for resynchronization therapy should be considered. According to the 2009 American College of Cardiology Foundation/AHA (ACCF/AHA) guidelines, biventricular pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) should be considered for patients in sinus rhythm with NYHA class III-IV symptoms, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 35%, and QRS greater than 120 ms. Consultation with an electrophysiologist is recommended.

The elements of long-term management of patients with CHF resulting from depressed LV systolic function are summarized in Table 23-1.

TABLE 23-1

ELEMENTS OF THE LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE DUE TO LEFT VENTRICULAR SYSTOLIC DYSFUNCTION

| Treatment/Intervention | Recommendation (Level of Evidence) |

| Diuretics for fluid retention | Class I (LOE: C) |

| Salt restriction | Class I (LOE: C) |

| ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) | Class I (LOE: A) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) in ACEI-intolerant patients | Class I (LOE: A) |

| ARB in persistently symptomatic patients with reduced LVEF already being treated with conventional therapy | Class IIb (LOE: C) |

| Hydralazine + Isosorbide in patients ACEI and ARB intolerant | Class IIb (LOE: C) |

| Hydralazine + Isosorbide in patients already on ACEI and β-blocker with persistent symptoms | Class IIa (LOE: A) |

| β-Blockers | Class I (LOE: A) |

| Digoxin in patients with heart failure symptoms. Generally used in those with continued symptoms and/or hospitalizations despite good therapy with diuretics and ACEIs | Class IIa (LOE: B) |

| Aldosterone antagonists in patients with moderate-severe symptoms who can carefully be monitored for renal function and potassium level and with baseline creatinine < 2-2.5 mg/dL and potassium < 5.0 mEq/L | Class I (LOE: B) |

| Exercise training in ambulatory patients | Class I (LOE: B) |

| ICD for “secondary prevention” (history of cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillation, or hemodynamically destabilizing ventricular tachycardia) | Class I (LOE: A) |

| ICD for “primary prevention” for LVEF < 30%-35% and symptomatic heart failure (see text) | Class I-IIa (LOE: A-B) |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy for patients in sinus rhythm with class III-IV symptoms despite medical therapy, LVEF < 35%, and QRS > 120 ms (see text) | Class I (LOE: A) |

Modified from Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al: ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 46:e1-e82, 2005.

7. How do ACE inhibitors and ARBs work?

ARBs selectively block the binding of angiotensin II to the AT1 receptor, thereby blocking the effect of angiotensin II on end organs. This results in attenuation of sympathetic tone, decrease in arterial vasoconstriction, and attenuation of myocardial hypertrophy. Because angiotensin II stimulates aldosterone production, circulating levels of aldosterone are reduced. This results in a decrease in sodium chloride absorption, potassium excretion in the distal tubules, and water retention.

8. What approach should be taken if a patient treated with an ACE inhibitor develops a cough?

9. What is the efficacy of ARBs compared with ACE inhibitors in patients with chronic heart failure?

10. When should ARBs be added to ACE inhibitors in patients with chronic heart failure?

Continue to have symptoms of heart failure despite receiving target doses of ACE inhibitors and β-blockers

Continue to have symptoms of heart failure despite receiving target doses of ACE inhibitors and β-blockers

Are taking ACE inhibitors but are unable to tolerate β-blockers and have persistent symptoms, if there are no contraindications

Are taking ACE inhibitors but are unable to tolerate β-blockers and have persistent symptoms, if there are no contraindications

11. How do aldosterone antagonists work?

12. List the indications and recommended dosing of aldosterone antagonists in heart failure.

Current indications include the following:

Chronic NYHA class III-IV heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction 35% or less; already receiving standard therapy for heart failure, including ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, and diuretics (based on the RALES trial with spironolactone [Aldactone]). The recent EMPHASIS trial with eplerenone demonstrated improvement in survival and heart failure hospitalizations in patients with mild (NYHA class II) heart failure symptoms and systolic heart failure suggesting a wider class of patients (NYHA class II-IV) may benefit from aldosterone antagonism.

Chronic NYHA class III-IV heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction 35% or less; already receiving standard therapy for heart failure, including ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, and diuretics (based on the RALES trial with spironolactone [Aldactone]). The recent EMPHASIS trial with eplerenone demonstrated improvement in survival and heart failure hospitalizations in patients with mild (NYHA class II) heart failure symptoms and systolic heart failure suggesting a wider class of patients (NYHA class II-IV) may benefit from aldosterone antagonism.

Post-MI LV dysfunction (ejection fraction less than 40%) and heart failure; already receiving standard therapy, including ACE inhibitors and β-blockers (EPHESUS study of eplerenone)

Post-MI LV dysfunction (ejection fraction less than 40%) and heart failure; already receiving standard therapy, including ACE inhibitors and β-blockers (EPHESUS study of eplerenone)

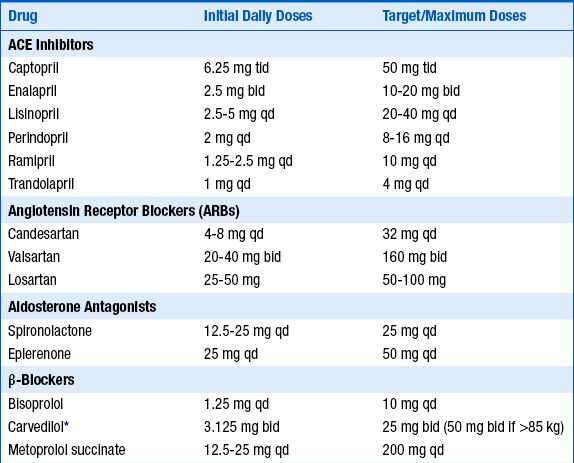

The initial and target doses for aldosterone antagonists and other drugs used to treat patients depressed systolic ejection fraction and/or CHF are listed in Table 23-2.

TABLE 23-2

INITIAL AND TARGET DOSES FOR COMMONLY USED DRUGS FOR PATIENTS WITH DEPRESSED SYSTOLIC EJECTION FRACTION AND/OR CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; bid, twice a day; qd, one a day; tid three times a day.

∗Extended-release carvedilol now available, although this preparation not specifically tested in heart failure.

Modified from Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al: ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 46:e1-e82, 2005.

13. Can all patients with heart failure safely be started on an aldosterone antagonist?

14. Describe common adverse effects of ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and aldosterone antagonists.

Common adverse effects include the following:

ACE inhibitors: hypotension, worsening renal function, hyperkalemia, cough, angioedema

ACE inhibitors: hypotension, worsening renal function, hyperkalemia, cough, angioedema

ARBs: hypotension, worsening renal function, hyperkalemia

ARBs: hypotension, worsening renal function, hyperkalemia

Aldosterone antagonists: hyperkalemia; renal dysfunction may be aggravated, may cause hypotension and hyponatremia

Aldosterone antagonists: hyperkalemia; renal dysfunction may be aggravated, may cause hypotension and hyponatremia

15. What are the indications and dosing of nitrates/hydralazine in patients with chronic heart failure?

Taking all the evidence together, the I/H combination is indicated in the following patients:

Those who cannot take an ACE inhibitor or ARB because of renal insufficiency or hyperkalemia

Those who cannot take an ACE inhibitor or ARB because of renal insufficiency or hyperkalemia

Those who are hypertensive and/or symptomatic despite taking ACE inhibitor, ARB, and β-blockers

Those who are hypertensive and/or symptomatic despite taking ACE inhibitor, ARB, and β-blockers

The combination of hydralazine and nitrates is recommended to improve outcomes for patients self-described as African Americans with moderate-severe symptoms on optimal medical therapy with ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, and diuretics.

The combination of hydralazine and nitrates is recommended to improve outcomes for patients self-described as African Americans with moderate-severe symptoms on optimal medical therapy with ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, and diuretics.

Hydralazine: start at 37.5 mg three times a day and increase to a goal of 75 mg three times a day.

Hydralazine: start at 37.5 mg three times a day and increase to a goal of 75 mg three times a day.

Isosorbide dinitrate: start at 20 mg three times a day and increase to a goal of 40 mg three times a day.

Isosorbide dinitrate: start at 20 mg three times a day and increase to a goal of 40 mg three times a day.

16. How should patients be treated with β-blockers?

Patients should not be initiated on β-blocker therapy during decompensated or hemodynamically unstable state heart failure.

Patients should not be initiated on β-blocker therapy during decompensated or hemodynamically unstable state heart failure.

β-Blocker therapy should only be initiated when patients are euvolemic and hemodynamically stable, are usually on a good maintenance dose of diuretics (if indicated), and receiving ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

β-Blocker therapy should only be initiated when patients are euvolemic and hemodynamically stable, are usually on a good maintenance dose of diuretics (if indicated), and receiving ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

β-Blockers should be initiated at low doses, uptitrated gradually (in at least 2-week intervals), and titrated to target doses shown to be effective in clinical trials (see Table 23-2). Practitioners should aim to achieve target doses in 8 to 12 weeks from initiation of therapy and to maintain patients at maximal tolerated doses.

β-Blockers should be initiated at low doses, uptitrated gradually (in at least 2-week intervals), and titrated to target doses shown to be effective in clinical trials (see Table 23-2). Practitioners should aim to achieve target doses in 8 to 12 weeks from initiation of therapy and to maintain patients at maximal tolerated doses.

If patient symptoms worsen during initiation or dose titration, the dose of diuretics or other concomitant vasoactive medications should be adjusted, and titration to target dose should be continued after the patient’s symptoms return to baseline.

If patient symptoms worsen during initiation or dose titration, the dose of diuretics or other concomitant vasoactive medications should be adjusted, and titration to target dose should be continued after the patient’s symptoms return to baseline.

If uptitration continues to be difficult, the titration interval can be prolonged, the target dose may have to be reduced, or the patient should be referred to a heart failure specialist.

If uptitration continues to be difficult, the titration interval can be prolonged, the target dose may have to be reduced, or the patient should be referred to a heart failure specialist.

If an acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure occurs, therapy should be maintained if possible; the dose can be reduced if necessary, but abrupt discontinuation should be avoided. If the dose is reduced (or discontinued), the β-blocker (and prior dose) should be gradually reinstated before discharge, if possible.

If an acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure occurs, therapy should be maintained if possible; the dose can be reduced if necessary, but abrupt discontinuation should be avoided. If the dose is reduced (or discontinued), the β-blocker (and prior dose) should be gradually reinstated before discharge, if possible.

17. What is the mechanism of action of digoxin?

18. Is there scientific evidence for the use of digoxin?

The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of 6801 symptomatic patients with heart failure and ejection fraction less than 45%, who were in sinus rhythm. Mean follow-up was 37 months. Patients already receiving digoxin were allowed into the trial and randomized to digoxin or placebo without a washout period. About 95% of patients in both groups received ACE inhibitors; β-blockers were not in use for heart failure at the time. The primary outcome was total mortality. Digoxin did not improve total mortality (34.8% versus 35.1% in the placebo group, P = 0.80) or deaths from cardiovascular causes (29.9% versus 29.5%, P = 0.78). Hospitalizations as a result of worsening heart failure (a secondary endpoint) were significantly reduced by digoxin (26.8% versus 34.7% in the placebo group, risk ratio 0.72, P < 0.001). Hospitalizations for suspected digoxin toxicity were higher in the digoxin group (2% versus 0.9%, P < 0.001). In an ancillary, parallel trial in patients with ejection fraction greater than 45% and sinus rhythm, the findings were consistent with the results of the main trial. Whether these results hold with contemporary heart failure treatment that includes β-blockers, aldosterone-receptor blockers, and resynchronization therapy is not known.

19. What are some of the relevant drug interactions of digoxin?

Quinidine, verapamil, amiodarone, propafenone, and quinine (used for muscle cramps) may double digoxin levels, and the dose of digoxin should be halved when used in combination with any of these drugs.

Quinidine, verapamil, amiodarone, propafenone, and quinine (used for muscle cramps) may double digoxin levels, and the dose of digoxin should be halved when used in combination with any of these drugs.

Tetracycline, erythromycin, and omeprazole can increase digoxin absorption, whereas cholestyramine and kaolin-pectin can decrease it.

Tetracycline, erythromycin, and omeprazole can increase digoxin absorption, whereas cholestyramine and kaolin-pectin can decrease it.

Thyroxine and albuterol increase the volume of distribution, resulting in decreased digoxin levels.

Thyroxine and albuterol increase the volume of distribution, resulting in decreased digoxin levels.

Cyclosporine and paroxetine and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can increase serum digoxin levels.

Cyclosporine and paroxetine and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can increase serum digoxin levels.

20. What are the clinical manifestations of digoxin toxicity?

21. What are the electrocardiographic findings of digoxin toxicity?

First- and second-degree AV block

First- and second-degree AV block

Paroxysmal atrial tachycardia with AV block (common)

Paroxysmal atrial tachycardia with AV block (common)

Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (rare but typical)

Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (rare but typical)

Regularized atrial fibrillation or atrial fibrillation with slow ventricular response (common)

Regularized atrial fibrillation or atrial fibrillation with slow ventricular response (common)

22. How is digoxin toxicity treated?

It depends on the clinical severity. Digoxin withdrawal is sufficient with only suggestive symptoms. Activated charcoal may enhance the gastrointestinal (GI) clearance of digoxin if given within 6 hours of ingestion. Drugs that increase plasma digoxin levels (see Question 19) should be discontinued (except amiodarone, because of its long half-life). Correction of hypokalemia is vital (intravenous [IV] replacement through a large vein is preferred with life-threatening arrhythmias), but judgment is needed in the presence of high degrees of AV block. Symptomatic AV block may respond to atropine or to phenytoin (100 mg IV every 5 minutes up to 1000 mg until response or side effects); if no response, use digoxin immune Fab (ovine) (Digibind). The use of temporary transvenous pacing should be avoided. Patients with severe bradycardia should be given Digibind, even if they respond to atropine. Lidocaine and phenytoin may be used to treat ventricular arrhythmias, but for potentially life-threatening bradyarrhythmias or tachyarrhythmias, Digibind should be used. IV magnesium may be given 2 grams over 5 minutes and has been shown to help with digoxin toxicity related arrhythmias. Dialysis has no role because of the high tissue-binding of digoxin.

23. What are the indications for Digibind?

24. What three classes of drugs exacerbate the syndrome of CHF and should be avoided in most CHF patients?

a. Antiarrhythmic agents. They can exert cardiodepressant and proarrhythmic effects. Only amiodarone and dofetilide have been shown not to adversely affect survival.

b. Calcium channel blockers. The nondihydropyridines can lead to worsening heart failure and have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Only the dihydropyridines or vasoselective calcium channel blockers have been shown not to adversely affect survival.

c. NSAIDs. According to the ACC/AHA guidelines, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can cause sodium retention and peripheral vasoconstriction and can attenuate the efficacy and enhance the toxicity of diuretics and ACE inhibitors. The European Society of Cardiology also cautions against the use of NSAIDs.

25. Is dietary restriction of sodium recommended in patients with symptomatic heart failure?

26. Is fluid restriction recommended in all patients with heart failure?

27. Should patients with CHF be told to use salt substitutes instead of salt?

28. What are the current criteria for consideration of CRT with biventricular pacing?

Class III or ambulatory class IV symptoms despite good medical therapy

Class III or ambulatory class IV symptoms despite good medical therapy

LVEF less than or equal to 35%

LVEF less than or equal to 35%

QRS more than 120 ms (especially if left bundle branch block morphology present)

QRS more than 120 ms (especially if left bundle branch block morphology present)

29. Which patients with heart failure should be considered for an ICD?

Secondary prevention (cardiac arrest survivors of ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation [VT/VF], hemodynamically unstable sustained VT)

Secondary prevention (cardiac arrest survivors of ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation [VT/VF], hemodynamically unstable sustained VT)

Structural heart disease and sustained VT, whether hemodynamically stable or unstable

Structural heart disease and sustained VT, whether hemodynamically stable or unstable

Syncope of undetermined origin with hemodynamically significant sustained VT or VF induced at electrophysiologic study

Syncope of undetermined origin with hemodynamically significant sustained VT or VF induced at electrophysiologic study

LVEF less than or equal to 35% at least 40 days after MI and NYHA functional class II-III

LVEF less than or equal to 35% at least 40 days after MI and NYHA functional class II-III

LVEF less than 30% at least 40 days after MI and NYHA functional class I

LVEF less than 30% at least 40 days after MI and NYHA functional class I

LVEF less than or equal to 35% despite medical therapy in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and NYHA functional class II-III

LVEF less than or equal to 35% despite medical therapy in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and NYHA functional class II-III

Nonsustained VT caused by prior MI, LVEF less than 40%, and inducible VF or sustained VT at electrophysiologic study

Nonsustained VT caused by prior MI, LVEF less than 40%, and inducible VF or sustained VT at electrophysiologic study

ICD therapy is recommended to improve survival in patients who have survived cardiac arrest or who have sustained VT, which is either poorly tolerated or associated with reduced systolic LV function (class I; level of evidence A).

ICD therapy is recommended to improve survival in patients who have survived cardiac arrest or who have sustained VT, which is either poorly tolerated or associated with reduced systolic LV function (class I; level of evidence A).

ICD implantation is reasonable in selected patients with LVEF less than 30% to 35%, not within 40 days of an MI, on optimal background therapy including ACE inhibitor, ARB, β-blocker, and an aldosterone antagonist, where appropriate, to reduce likelihood of sudden death (class I; level of evidence A).

ICD implantation is reasonable in selected patients with LVEF less than 30% to 35%, not within 40 days of an MI, on optimal background therapy including ACE inhibitor, ARB, β-blocker, and an aldosterone antagonist, where appropriate, to reduce likelihood of sudden death (class I; level of evidence A).

ICD implantation in combination with biventricular pacing can be considered in patients who remain symptomatic with severe heart failure, NYHA class III-IV, with LVEF 35% or less and QRS 120 ms or more to improve mortality or morbidity (class IIa; level of evidence B).

ICD implantation in combination with biventricular pacing can be considered in patients who remain symptomatic with severe heart failure, NYHA class III-IV, with LVEF 35% or less and QRS 120 ms or more to improve mortality or morbidity (class IIa; level of evidence B).

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Arnold, J.M.O., Heart Failure (HF) 2012 Available at http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/cardiovascular_disorders/heart_failure/heart_failure_hf.html Accessed March 19, 2013

2. Cooper, L.T., Baughman, K.L., Feldman, A.M., et al. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology. Endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America and the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1914–1931.

3. Epstein, A.E., DiMarco, J.P., Ellenbogen, K.A., et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices) developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:e1–e62.

4. Heart Failure Society of America. The HFSA website. Available at http://www.hfsa.org. Accessed March 19, 2013

5. Heart Failure Society of America. Heart failure in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail. 2006;12:e38–e57.

6. Hunt, S.A., Abraham, W.T., Chin, M.H., et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:e1–e82.

7. Jessup, M., Abraham, W.T., Casey, D.E., et al. Focused Update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016.

8. Mann, D.L. Management of heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. In Libby P., Bonow R., Mann D., eds.: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

9. Swedberg, K., Cleland, J., Dargie, H., et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: executive summary (update 2005): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1115–1140.

10. Dumitru, I. Heart Failure. Available at http://www.emedicine.com. Accessed March 19, 2013