HEART FAILURE

The typical ‘textbook person’ at rest has a cardiac output of about 5 L/min (see Chapter 4). The key physiological variables determining cardiac output are grouped as follows:

• preload events (filling pressure of the ventricle)

• contractility events (events inside the myocyte particularly associated with [Ca++] and [H+])

• afterload events (the resistance to blood leaving the heart)

The first three items on this list determine the stroke volume of each ventricle and the heart rate is primarily regulated by the baroreceptor reflex which keeps arterial blood pressure quite constant (see Chapter 9).

In Case 6.1:1 the history is outlined of a 37-year-old man who finds that his exercise capacity is becoming limited.

Systolic vs diastolic failure

In general the causes of heart failure can be attributed to one or more of the following:

• decreased myocyte contractility

• inappropriate workload due to pressure overload (e.g. hypertension causing increased afterload) or volume overload (increased preload)

Heart failure may result from functional changes affecting either systole or diastole or both. Table 6.1 summarizes some of the key differences between systolic and diastolic heart failure. Examples of these different forms of cardiac failure are:

Table 6.1

Some characteristic differences between systolic and diastolic heart failure

| Systolic heart failure | Diastolic heart failure | |

| Systolic BP | Low normal; hypertension | Low normal; hypertension |

| End-diastolic volume | ↑↑ | Normal or ↓ |

| End-systolic volume | ↑↑ | ↓ |

| Stroke volume | Normal or ↓ | Normal or ↓ |

| Ejection fraction | ↓↓ | Normal |

| Myocardial hypertrophy | Eccentric | Concentric |

| LV wall thickness | ↓ | ↑↑ |

| Extracellular matrix | ↓ | ↑↑ |

It is widely thought that cardiac myocytes cannot proliferate, only change size and shape. Some recent reports however suggest limited myocyte division is possible after myocardial infarction. In eccentric hypertrophy extra sarcomeres (see Fig. 2.1) are added in series and so myocyte length increases leading to a dilated heart. In concentric hypertrophy extra sarcomeres are added in parallel and so myocyte diameter increases.

Haemodynamic events

Haemodynamic events in systolic heart failure

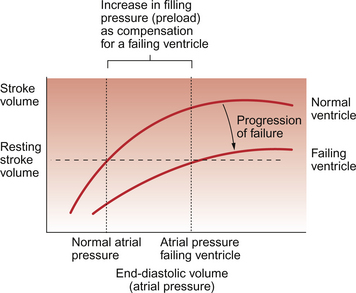

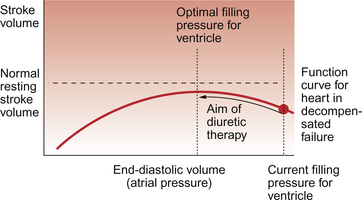

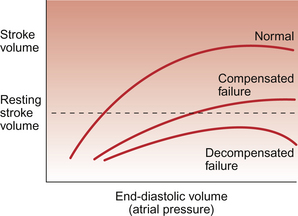

If the degree of functional impairment of the heart is relatively small then at rest the ventricle may be able to maintain a normal stroke volume and hence a normal cardiac output. This is achieved by an increase in filling pressure of the ventricle and hence an increase in end-diastolic volume. This increase in ‘preload’ causes the impaired ventricular function to move up a Starling curve (see Chapter 4) to reach a normal stroke volume (Fig. 6.1). There is however a limitation on the ability to increase stroke volume above the resting levels. This manifests itself as part of the exercise limitation experienced by heart failure patients. The increase in preload to restore resting stroke volume for a damaged heart to normal levels is referred to as ‘compensation’.

The extent to which compensation can occur is limited by the shape of the cardiac function curve. If end-diastolic volume increases too much then a plateau is reached when further increases in end-diastolic volume do not produce a corresponding increase in the force of contraction of the ventricle. If the cardiac output is still inadequate when this plateau region is reached then end-diastolic volume may continue to increase and this will eventually cause the force of contraction to decrease. This is the region of ‘decompensation’ on the Starling curve and may rapidly lead to death (Fig. 6.2).

Fig. 6.2 Decompensated cardiac failure. In compensated cardiac failure the resting stroke volume and therefore resting cardiac output can reach normal levels by virtue of an increase in filling pressure (preload) for the ventricle (see Fig. 6.1). In decompensated failure increases in preload fail to achieve a satisfactory cardiac output and further increases may lead to a decline in stroke volume.

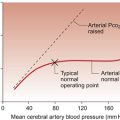

The commonest form of heart failure is left ventricle systolic failure. It has an annual mortality rate of 15–30% depending on disease severity. In pure left heart failure, the healthy right ventricle will continue to pump blood into the lungs until left ventricular preload is increased enough to restore ventricular balance, i.e. the same output from the two sides of the heart. This ventricular balance will be achieved at the price of raised left atrial, pulmonary capillary and pulmonary artery pressures. The raised pulmonary capillary pressure may result in pulmonary oedema (see Chapter 11) and this will cause the lungs to become ‘stiff’. There will be an increased resistance to inflation of the lungs (a decreased compliance) and this will produce a sensation of breathlessness (dyspnoea). The pulmonary oedema may also upset the balance between the distribution of lung ventilation and pulmonary blood flow causing a ‘ventilation-perfusion mismatch’ which will result in arterial hypoxaemia. This in turn will further reduce the delivery of oxygen to the heart and potentially exacerbate heart failure, producing a vicious circle of events.

The commonest cause of right heart failure is left heart failure. The right ventricle fails because of the increased afterload (increased pulmonary circuit blood pressure) produced by the left-sided failure. Right heart failure may also follow from a raised pulmonary vascular resistance (hypoxic vasoconstriction) such as may occur during decreased oxygenation of the blood in lung disease or in response to low oxygen pressures at altitude (see Chapter 9). The condition of right heart failure resulting from increased pulmonary vascular resistance or some other aspect of lung dysfunction leading to pulmonary artery hypertension is known as cor pulmonale.

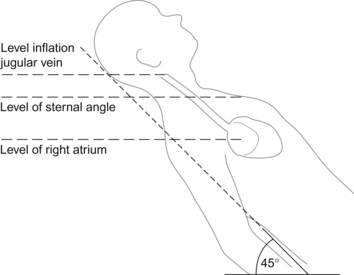

In right heart failure ventricular output may be maintained by an increased preload (right atrial pressure; RAP). Clinically it is possible to assess RAP by monitoring jugular venous pressure (Box 6.1). An increase in right atrial pressure will lead to an increase in pressure back through the vena cava and peripheral veins and capillaries and will result in peripheral oedema (see Chapter 11). This is manifested by ankle oedema (if the subject is standing or seated) or sacral oedema (if they are supine). There may also be enlargement of the liver which becomes palpable below the lower ribs. However it should be remembered that the most common cause of ankle swelling in the elderly is not right heart failure but immobility or vascular disease.

Haemodynamic events in diastolic heart failure

The characteristics of diastolic heart failure are delayed relaxation of the ventricle and impaired filling of the left ventricle often linked to increased stiffness of the ventricular wall. Mitral and/or tricuspid valve stenosis will also lead to diastolic dysfunction by providing an increased resistance to atrial emptying. If left-sided heart failure is purely associated with diastole then the ejection fraction (EF) of the ventricle (stroke volume expressed as a percentage of end-diastolic volume) will be normal or only slightly reduced at 40–50%. There will be an increase in left atrial pressure and pulmonary congestion secondary to raised pulmonary capillary pressure. Diastolic failure is typically seen in patients with cardiac hypertrophy (often as a result of hypertension) or restrictive problems such as the fibrotic changes which occur in amyloidosis or in pericarditis. These problems may be exacerbated by any tachycardia, as when the heart rate increases the time available for diastole is shortened more than the time available for systole (see Chapter 5).

Metabolic events in heart failure

In Chapter 5 the regulation of coronary blood flow is described. Impaired blood supply will lead to reduced ATP generation and impaired ventricular muscle performance. In Chapter 2 the roles of ATP in systole and diastole are described. Each cycle of cross-bridge formation requires the binding of a Ca++ ion to troponin C and the hydrolysis of an ATP molecule in order to achieve cardiac myocyte contraction during systole. ATP is also essential for myocyte relaxation during diastole as Ca++ must be actively pumped back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum stores. Changes in intracellular [Ca++] are the major factor determining the contractility of cardiac muscle (see Chapter 4).

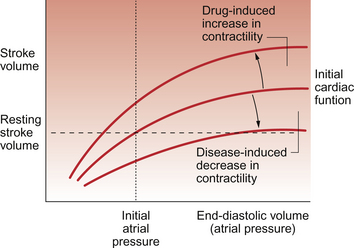

Dysfunction of the mechanisms regulating cardiac contractility (Fig. 6.4) are important in the initiation and progression of some forms of heart failure. The defects are thought to be associated with altered sarcoplasmic reticulum uptake, storage and release of Ca++. In experimental animal studies of heart failure it has been shown that maintaining contractility can prevent the development of cardiac failure. This is however a complex and still developing area. Clinical trials have shown that improving contractility by the use of positive inotrope agents (see p. 68) which increase intracellular [cAMP] have tended to increase mortality. Cardiac glycosides are drugs which increase intracellular [Ca++] and hence contractility by a different mechanism compared to sympathomimetic drugs (Fig. 6.5). They are only relatively weak inotropes and neither increase nor decrease mortality among patients with congestive heart failure but do provide symptomatic relief. Further aspects of the actions of these drugs are discussed below and in Chapter 2.

Different ways of altering cardiac myocyte contractility using drugs which do not involve increased cAMP formation are being evaluated. In this context the Na+/Ca++ exchange mechanism in the sarcolemma is of considerable interest (see Fig. 2.3).

In relation to drug therapy, low doses of β-adrenoceptor antagonists, which in the short term have negative inotropic actions and were therefore previously thought to be contraindicated, seem to have beneficial effects in relation to reversal of cardiac remodelling (see p. 67), increase in contractility and in improving patient survival. Some aspects of the mechanisms behind these beneficial effects of beta-blockers are still a matter for conjecture.

A further component of the metabolic changes in heart failure is the role played by H+ ions. As described in Chapter 4, H+ ions are the strongest naturally occurring negative inotrope and the actions involved include decreased binding of Ca++ to troponin C. Underventilation of the lung and the consequent increases in the Pco2 of body fluids leads to respiratory acidosis (see Chapter 1). Oxidative metabolism also generates forms of acid which have to be excreted via the kidneys. Overproduction of such acids, as in diabetic ketoacidosis, or a failure of excretory mechanisms as in renal failure, will lead to metabolic acidosis. Either form of acidosis, but particularly respiratory acidosis (as CO2 can quickly diffuse into the myocyte), is likely to impair myocyte contraction and make heart failure worse.

Neurohormonal aspects of Heart Failure

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system is a central component of the physiological response to heart failure and the mechanisms involved, the baroreceptor reflex, are described in Chapter 10. Sympathetic activation may be manifested as an increased heart rate, which is not necessarily helpful for a patient with a poorly functioning ventricle. Other characteristics of increased sympathetic drive include:

• Increased contraction of venous smooth muscle will contribute to increased right ventricle preload and therefore to compensation in moderate heart failure (Fig. 6.1).

• Vasoconstriction, particularly in the skin, splanchnic circulation and skeletal muscle, will help to sustain arterial blood pressure (the driving force for tissue perfusion) and divert available cardiac output to the most critical organs (heart and brain).

• Increased contractility of cardiac myocytes by a β-adrenoceptor mediated increase in intracellular [Ca++].

• Increased renin secretion from the juxtaglomerular cells in the kidney (see below).

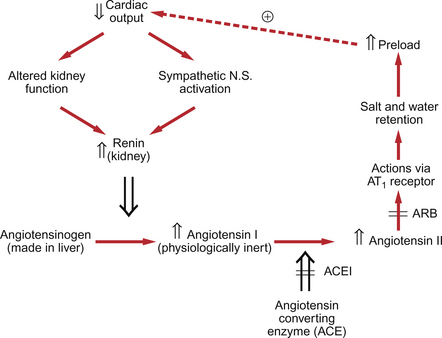

Figure 6.1 shows that the compensation response for cardiac failure is an increase in preload (increased end-diastolic volume or atrial pressure) on the heart. This is largely achieved by an expansion of the extracellular fluid volume, including blood volume, driven by activation of the renin-angiotensin system. Increased renin secretion occurs in response to decreased blood pressure or to any situation in which blood volume is inadequate to support the necessary preload for an appropriate cardiac output. The components of the renin-angiotensin system are summarized in Figure 6.6 and are further discussed in Chapters 9 and 14. The mechanisms regulating renin secretion from the juxtaglomerular (JG) cells in the kidney may be summarized as:

• Direct innervation of JG cells by sympathetic nerves which act through a β-adrenoceptor mechanism. Renin secretion will therefore be increased as part of the baroreceptor reflex (see Chapter 10).

• JG cells are intrinsically sensitive to stretch. A fall in renal afferent arteriole pressure will lead to increased renin secretion. This mechanism is independent of the sympathetic nervous system.

• A putative Na+ and/or Cl− load detector located at the macula densa, a group of specialized tubular cells where the ascending limb of the loop of Henle becomes the distal tubule as it passes the JG cells. It is still unclear exactly how or if this mechanism functions to control renin secretion.

• Circulating angiotensin II (Ang II) concentration exerts a negative feedback control on renin secretion via an AT1 receptor on the JG cells.

Increased Ang II concentration increases sodium and water retention via stimulation of the synthesis of aldosterone in the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex and also via direct effects of Ang II on sodium transport mechanisms in the nephron. Ang II will also increase antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion which further contributes to fluid retention. If the expansion of blood volume fails to generate an adequate arterial blood pressure which would eventually suppress renin secretion, this will lead to excessive expansion of the extracellular fluid compartment. This may lead to further deterioration of cardiac performance and to decompensated failure (Fig. 6.2). This scenario provides part of the rationale for the use of diuretics and blockers of the renin system (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and Ang II receptor blockers) in the management of heart failure (see p. 68). Overproduction of Ang II also contributes to the series of fibrotic changes in the heart known as remodelling. This seems to start as an adaptive response to changes in cardiac function but as failure progresses remodelling becomes counterproductive.

The potent vasoconstrictor peptide endothelin-1 (ET-1) (see Chapter 9) has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of congestive heart failure. Initially in an adaptive context ET-1 is thought to have a positive role promoting inotropic actions on the myocyte and increasing myocyte protein synthesis. Overexpression of ET-1 leads to myocardial fibrosis and myocyte necrosis in addition to local vasospasm, all of which promote the progression of failure. Endothelin production may be potentiated by the increased concentrations of Ang II which frequently occur in heart failure (see p. 66).

The two types of endothelin receptors are designated ETA and ETB (see Chapter 9), and drugs which block these receptors are given trivial names ending in -sentan. Drugs such as the non-selective ETA/ETB receptor blocker bosentan are undergoing clinical trials to evaluate their efficacy in the management of heart failure. It is not yet clear whether mixed ETA/ETB blockers or selective ETA receptor blockers will be the more valuable approach.

Drug therapy for heart failure

Sympathomimetic inotropes

This group includes drugs such as isoprenaline/isoproterenol (a non-selective β1/β2 agonist), dobutamine (a selective β1 agonist) and dopamine (a non-selective β-adrenoceptor agonist which is also a dopamine D1/D2 receptor agonist). These drugs are given intravenously to acutely ill hospitalized patients in order to provide a short-term increase in cardiac contractility. β-adrenoceptor activation leads to an increase in myocyte [cAMP] and hence an increase in intracellular [Ca++] (see Chapter 2). Activation of D1 receptors by dopamine also leads to vasodilatation within the kidney and activation of presynaptic D2 receptors leads to peripheral vasodilatation by inhibition of noradrenaline (norepinephrine) release from sympathetic nerve endings. Dopamine-induced hypotension but with increased renal blood flow and increased cardiac contractility is often a useful combination in the management of heart failure. Dobutamine has positive inotropic actions but, compared to isoprenaline, a reduced effect increasing heart rate.

Adverse effects on patient mortality of drugs which increase intracellular [cAMP] have been referred to on page 65. In prolonged use of β-adrenoceptor agonists, downregulation of receptor number will also limit their therapeutic response.

The apparently counter-intuitive use of low dose beta-blockers in heart failure is described on page 65.

Digitalis glycosides

The most widely used drug in this category is digoxin which acts as an inhibitor of the Na+/K+-ATPase in cardiac muscle (see Fig. 4.7). The consequent increase in intracellular [Na+] results in reduced Na+/Ca++ exchange across the plasma membrane and so Ca++ is retained within the cell. The increase in intracellular [Ca++] provides an increase in myocardial contractility.

Although a relatively mild inotrope, digoxin can be used for an extended period provided the potential unwanted effects are kept under review. The digitalis glycosides have a narrow therapeutic window between doses which are too low to be effective and doses which are high enough to cause significant side effects. Toxicity may result from excessive increases in intracellular [Ca++] which may cause various arrhythmias. There may also be increased vagal activity causing an excessive atrioventricular (AV) node block (see Chapter 2). Anorexia, nausea and vomiting are quite common side effects as are neurological disturbances including fatigue, vertigo and visual disturbances. Digitalis toxicity will be worse if it is accompanied by hypokalaemia and thus care must be taken when combining digitalis treatment with diuretics. Renal failure, hypoxaemia and hypothyroidism will also increase the risk of toxicity.

Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) have an established role in the management of heart failure. Increasingly angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) which have many similar, but some importantly different, pharmacological actions compared to ACEI are being used (Fig. 6.5). The names of all of the ACEI family of drugs end in -pril (e.g. captopril, ramipril) and all the ARB family end in -sartan (e.g. losartan, valsartan).

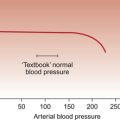

Initially ACEI were thought to be useful in heart failure by virtue of their effects reducing preload on the heart by blocking angiotensin/aldosterone-induced salt and water retention. They also reduce afterload effects on the heart by blocking the vasoconstrictor actions of Ang II and hence lower arterial blood pressure. In a normal heart reducing afterload (arterial blood pressure in this case) has a minimal effect on cardiac performance. In a failing heart however a reduction in arterial blood pressure may significantly improve stroke volume of the heart. However, it has subsequently emerged that blockade of the renin system also results in a reversal of the cardiac hypertrophy and adverse fibrotic changes in the failing heart which together are known as remodelling. These aspects of renin system inhibition are associated with improved patient mortality. Blockade of the renin system will also reduce aldosterone and endothelin production (see Chapter 9).

Diuretics

Diuretics remain the primary group of drugs used for the management of heart failure. The selection of the diuretic used depends on the severity of the failure. For mild cases a thiazide diuretic is used, but for many patients a loop diuretic, mainly furosemide (frusemide), is necessary. A potassium sparing diuretic (amiloride or spironolactone) may be appropriate if hypokalaemia occurs. The primary aim of diuretic therapy is to return preload to the optimal level on the Starling curve (Fig. 6.6). It is important to avoid hyponatraemia, hypokalaemia, excessive volume depletion and renal impairment. On the basis of encouraging results from randomized controlled clinical trials a new group of selective aldosterone receptor antagonists which do not have the unwanted side effects of spironolactone is being developed.

Braunwald, E. A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980.

Diwan, A., Dorn, G. W. Decompensation of cardiac hypertrophy: cellular mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Physiology. 2007; 22:56–64.

Gaasch, W. H., Zile, M. R. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure. Ann. Rev. Med.. 2004; 55:373–394.

Houser, S. R., Margulies, K. B. Is depressed myocyte contractility centrally involved in heart failure? Circ. Res.. 2003; 92:350–358.

Mandinov, L., Eberli, R. F., Seiler, C., Hess, O. M. Diastolic heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res.. 2000; 45:813–825.

Mann, D. L., Deswal, A., Bozkurt, B., Torre-Amione, G. New therapeutics for chronic heart failure. Ann. Rev. Med.. 2002; 53:59–74.

Orchard, C. H., Kentish, J. C. Effects of changes of pH on the contractile function of cardiac muscle. Am. J. Physiol.. 1990; 358:C967–C981.

Schillinger, W., Fiolet, J. W., Schlotthauer, K., Hasenfuss, G. Relevance of Na+-Ca++ exchange in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res.. 2003; 57:921–933.

Timmis, A. D., Davies, S. W. Heart failure. London: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992.

Waller, D. G., Renwick, A. G., Hillier, K. Medical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, third ed. Edinburgh: WB Saunders; 2009.