46 Heart Failure

Etiology And Presentation

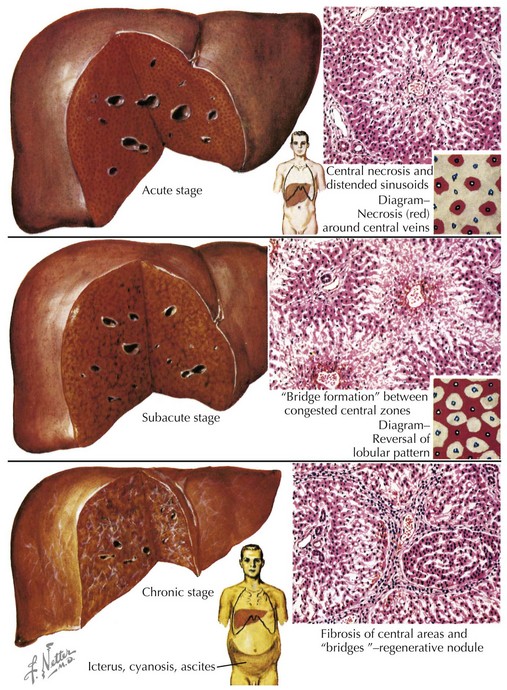

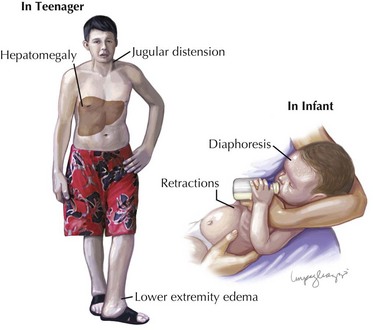

When the heart fails to adequately pump blood forward for any reason, venous congestion occurs. On the right side, the liver in particular becomes distended and engorged with blood. This leads to abdominal discomfort or vomiting initially, but in certain prolonged cases, it may lead to liver dysfunction and distension of venous collaterals, some of which may be visible under the skin (Figure 46-1). The signs of peripheral edema and jugular venous distension (Figure 46-2, left), classically seen in adults are not typically seen in infants or young children. On the left side, pulmonary venous congestion leads to fluid extravasation within the lungs, typically interstitial in infants and intraalveolar in older children and adults (Figure 46-2, right). This leads to shortness of breath, tachypnea, and dyspnea and can present on chest radiography similar to pneumonia. Indeed, in some cases, a secondary infection may develop superimposed on these wet and stiff lungs.

Berlin Heart. 500th Patient Receives Berlin Heart EXCOR Pediatric Ventricular Assist Device. Available at http://www.berlinheart.com/500th_EXCOR_Pediatric_Patient_full_story.pdf, 2009.

Bowles NE, Ni J, Kearney DL, et al. Detection of viruses in myocardial tissues by polymerase chain reaction. evidence of adenovirus as a common cause of myocarditis in children and adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:466-472.

Cooper LT, Baughman KL, Feldman AM, et al. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology Endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America and the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:3076-3093.

Gong F, Hu Y, Chen L, Gu W. The therapeutic effect of intravenous immunoglobulins and vitamin C on the progression of experimental autoimmune myocarditis in the mouse. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:BR240-246.

McCarthy RE, Boehmer JP, Hruban RH, et al. Long-term outcome of fulminant myocarditis as compared with acute (nonfulminant) myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:690-695.

Towbin JA, Bricker JT, Garson A. Electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in childhood. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1545-1548.

Udi N, Yehuda S. Intravenous immunoglobulin—indications and mechanisms in cardiovascular diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7:445-452.