Health and wellness: the beginning of the paradigm

Definitions and relationships among terms

The classic understanding of the term health from a biomedical perspective is “absence of disease.” The antonym of health, therefore, is disease. The World Health Organization contributed to the confusion between the terms health and wellness when in 1948 it defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”1 Indeed, there are numerous illustrations of the influence of the mind and spirit on the body and thus the importance, from a public health perspective, of considering more than the physical state of the body when formulating solutions to health problems. However, there is also value in differentiating health from more global concepts such as wellness and quality of life, if for no other reason than to explain the phenomenon that an individual can be diseased and well or can experience a high quality of life while simultaneously living with a chronic disease. Considering the catastrophic nature of many neurological diseases that compromise physical health, it is even more important to distinguish between health and wellness to recognize and pursue avenues to enhance overall quality of life and well-being.

H. L. Dunn first conceptualized the term wellness in 1961 and offered the first definition of the term: “an integrated method of functioning which is oriented toward maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable.”2 Since Dunn’s introduction of the term, numerous researchers and educators have attempted to explain wellness by proposing various models and approaches.3–11 Although the literature is full of references to and information about wellness, including numerous definitions of the term, a universally accepted definition has failed to emerge. Several conclusions can be drawn, however, from the abundance of literature regarding wellness.

For many people, including the public, health and wellness are synonymous with physical health or physical well-being, which commonly consists of physical activity, efforts to eat nutritiously, and adequate sleep. Research has indicated that when the public is asked to rate their general health, they narrowly focus on their physical health status, choosing not to consider their emotional, social, or spiritual health.12 Referring to the definition of wellness from Dunn, and consistent with numerous other theorists, it is obvious that wellness, as it is defined, includes more than just physical parameters.

The common themes that emerge from the various models and definitions of wellness suggest that wellness is multidimensional,2,4–13 salutogenic or health causing,* and consistent with a systems view of persons and their environments.2,15–17 Each of these characteristics will be explored.

First, as a multidimensional construct, wellness is more than simply physical health, as the more common understanding of the term might suggest. Among the dimensions included in various wellness models are physical, spiritual, intellectual, psychological, social, emotional, occupational, and community or environmental.18 Adams and colleagues18 in 1997, toward the aim of devising a wellness measurement tool, proposed six dimensions of wellness on the basis of the strength and quality of the theoretical support in the literature. The six dimensions and their corresponding definitions are shown in Table 2-1.

TABLE 2-1

DEFINITIONS OF THE DIMENSIONS OF WELLNESS18

| Emotional | The possession of a secure sense of self-identity and a positive sense of self-regard |

| Intellectual | The perception that one is internally energized by the appropriate amount of intellectually stimulating activity |

| Physical | Positive perceptions and expectancies of physical health |

| Psychological | A general perception that one will experience positive outcomes to the events and circumstances of life |

| Social | The perception that family or friends are available in times of need, and the perception that one is a valued support provider |

| Spiritual | A positive sense of meaning and purpose in life |

The second characteristic of wellness is that it has a salutogenic or health-causing focus,14 in contrast to a pathogenic focus in an illness model. Emphasizing the factors that cause health (e.g., salutogenic) supports Dunn’s2 original definition, which implied that wellness involves “maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable.” In other words, wellness is not just preventing illness or injury or maintaining the status quo; rather, it involves choices and behaviors that emphasize optimal health and well-being beyond the status quo. Thus an individual may or may not be well before pathological conditions and health conditions involve the body and similarly may be well during an acute episode or chronic pathology or health condition whether that chronic problem results in static activity limitations or even progressive participation restrictions.

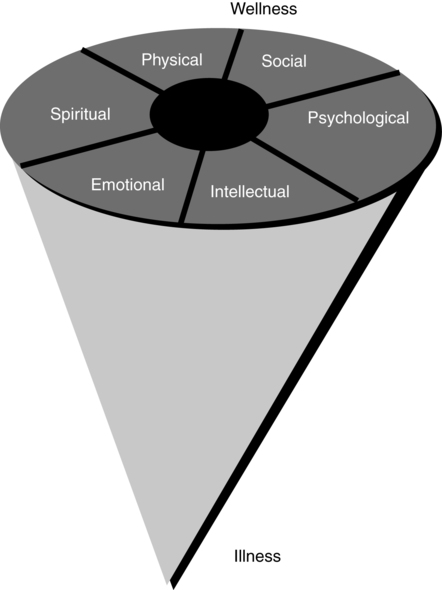

Third, wellness is consistent with a systems perspective. In systems theory each element of a system is independent and contains its own subelements, in addition to being a subelement of a larger system.12,15,16 Furthermore, the elements in a system are reciprocally interrelated, indicating that a disruption of homeostasis at any level of the system affects the entire system and all its subelements.15,16 Therefore overall wellness is a reflection of the state of being within each dimension and a result of the interaction among and between the dimensions of wellness. Figure 2-1 illustrates a model of wellness reflecting this concept. Vertical movement in the model occurs between the wellness and illness poles as the magnitude of wellness in each dimension changes. The top of the model represents wellness because it is expanded maximally, whereas the bottom of the model represents illness. Bidirectional horizontal movement occurs within each dimension along the lines extending from the inner circle. As per systems theory, movement in every dimension influences and is influenced by movement in the other dimensions.18 As an example, an individual who has a knee injury and undergoes surgery to repair the anterior cruciate ligament will probably have at least a short-term decrease in physical wellness. Applying systems theory and according to the model, this individual may also have a decrease in other dimensions such as emotional or social wellness in the postoperative period. The overall effect of these changes in these dimensions will be a decrease in overall wellness, which anecdotally we know occurs when patients have an illness or injury.

The wellness model.

The wellness model.A term related to wellness, quality of life, is also used to indicate the subjective experience of an individual in a larger context beyond just physical health. Quality of life has been defined as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, and their relationship to salient features of their environment.”19 Parallel to the issues related to the concept of wellness, there is lack of agreement in the literature on the definition of quality of life and its theoretical components,20–23 as well as variation in the use of subjective or objective quality-of-life indicators.21 Implied by the World Health Organization definition, and supported by several other authors, quality of life is best conceptualized as a subjective construct that is measured through an examination of a client’s perceptions. In other words, quality of life, like wellness, is the subjective experience of health, illness, activity and participation, the environment, social support, and so forth, and it is best measured through an assessment of client perceptions.

A wellness paradigm

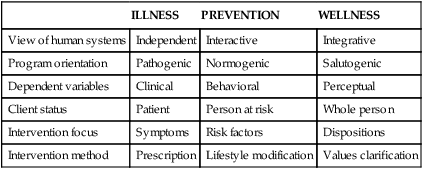

The ultimate importance of gaining an understanding of health and wellness is to be able to apply it when interacting with patients/clients. In this sense, the goal would be to improve the health and well-being of the client, in addition to improving movement and participation. A comparison of the traditional “illness” paradigm with both “prevention” and “wellness” paradigms will identify ways in which a physical or occupational therapist can incorporate a wellness paradigm into the treatment of a patient with a neurological condition in the context of rehabilitation. The three approaches or paradigms are contrasted in Table 2-2 on six parameters, including the view of human systems, program orientation, dependent variables, client status, intervention focus, and intervention method.

TABLE 2-2

| ILLNESS | PREVENTION | WELLNESS | |

| View of human systems | Independent | Interactive | Integrative |

| Program orientation | Pathogenic | Normogenic | Salutogenic |

| Dependent variables | Clinical | Behavioral | Perceptual |

| Client status | Patient | Person at risk | Whole person |

| Intervention focus | Symptoms | Risk factors | Dispositions |

| Intervention method | Prescription | Lifestyle modification | Values clarification |

The program orientation of an illness paradigm is the pathology or disease-causing issue, whereas the orientation of a prevention paradigm is normogenic, meaning efforts are aimed at maintaining a normal state or condition (e.g., normal muscle length, tone). Shifting to a wellness paradigm requires a salutogenic or health-causing approach,14 with a focus on how to achieve greater well-being, health, or quality of life. This shift emphasizes the capabilities and abilities of the individual rather than the limitations and deficits.

The variables of interest in an illness paradigm are clinical variables, such as blood tests, V.o2max (maximum volume of oxygen use), and tests of muscle strength. Changes in these variables result in labeling the patient more or less ill. In a prevention paradigm, the variables measured are behavioral—for example, whether the individual smokes, exercises, or wears a helmet. Positive improvement in a prevention approach typically results in a change in an individual’s behavior. In contrast, the variables measured in a wellness paradigm are perceptual, indicating what the patient/client thinks and feels about herself or himself. Although clinical, physiological, and behavioral variables are useful indicators of bodily wellness and are commonly used to plan individual and community interventions, their utility as wellness measures falls short.24 Clinical and physiological measures assess the status of a single system, most commonly the systems within the physical domain of wellness. It can be argued that behavioral measures are a better reflection of multiple systems because of the importance and influence of motivation and self-efficacy on the adoption of behaviors, but they do not describe the wellness of the mind. On the other hand, perceptual measures, capable of assessing all systems and having been shown to predict effectively a variety of health outcomes,18,25–29 can complement the information provided by body-centered measures insofar as they are valid, congruent with wellness conceptualizations, and empirically supportable.24

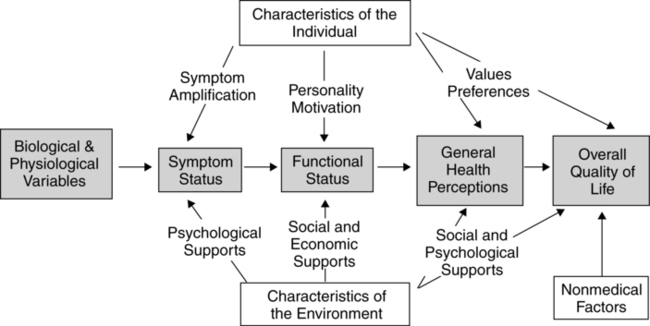

The influence of perceptions on health and wellness has been demonstrated repeatedly in the literature with a multiplicity of patient/client populations and in a variety of settings. Mossey and Shapiro25 demonstrated more than 25 years ago that self-rated health was the second strongest predictor of mortality in the elderly, after age. Numerous other researchers have replicated these findings in other populations, lending support to the value of perceptions in understanding health and wellness and indicating that how well you think you are may be more important than how well you are as measured by clinical tests and measures or the judgment of a health professional. Wilson and Cleary24 argued for the use of perceptions in understanding and explaining quality of life, proposing that health perceptions provide an important link between the biomedical model or clinical/illness paradigm, with its focus on “etiological agents, pathological processes, and biological, physiological, and clinical outcomes,” and the quality-of-life model or social science paradigm, with its focus on “dimensions of functioning and overall well-being”24 (Figure 2-2). Citing studies that have used perceptual measures, including the Mossey and Shapiro25 study, Wilson and Cleary24 state that health perceptions “are among the best predictors of [outcomes from] general medical and mental health services as well as strong predictors of mortality, even after controlling for clinical factors.”24

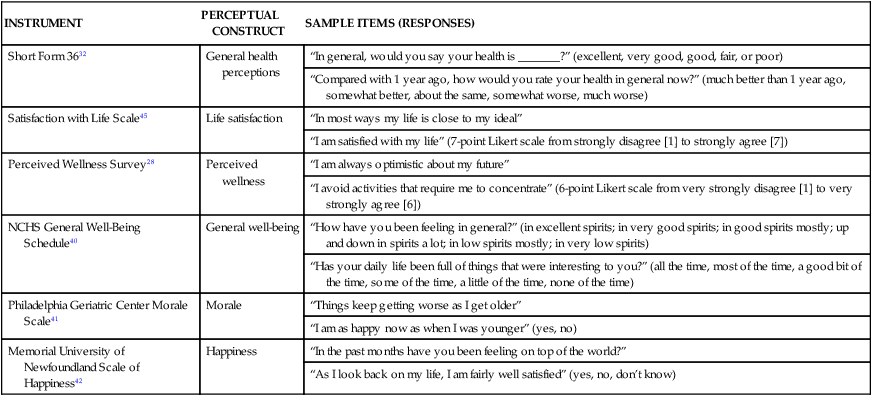

Consistent with the client status elements, the focus of intervention in an illness paradigm is on symptoms and in a prevention approach on risk factors. Consistent with a whole-person focus in a wellness approach, the intervention focuses on dispositions. Defined as a prevailing tendency, mood, or inclination or the tendency to act in a certain manner under given circumstances, dispositions produce perceptions, which can be measured to indicate a global or psychosocial assessment of the whole person, given input from all of the systems. Combined with symptom and risk factor assessment, perceptions of the individual provide valuable additional information about a client that can enhance the therapists’ ability to intervene and the success of the interventions selected. Table 2-3 lists a few measurement tools that assess client perceptions.

TABLE 2-3

SAMPLE ITEMS FROM PERCEPTUAL MEASUREMENT TOOLS

| INSTRUMENT | PERCEPTUAL CONSTRUCT | SAMPLE ITEMS (RESPONSES) |

| Short Form 3632 | General health perceptions | “In general, would you say your health is _______?” (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) |

| “Compared with 1 year ago, how would you rate your health in general now?” (much better than 1 year ago, somewhat better, about the same, somewhat worse, much worse) | ||

| Satisfaction with Life Scale45 | Life satisfaction | “In most ways my life is close to my ideal” |

| “I am satisfied with my life” (7-point Likert scale from strongly disagree [1] to strongly agree [7]) | ||

| Perceived Wellness Survey28 | Perceived wellness | “I am always optimistic about my future” |

| “I avoid activities that require me to concentrate” (6-point Likert scale from very strongly disagree [1] to very strongly agree [6]) | ||

| NCHS General Well-Being Schedule40 | General well-being | “How have you been feeling in general?” (in excellent spirits; in very good spirits; in good spirits mostly; up and down in spirits a lot; in low spirits mostly; in very low spirits) |

| “Has your daily life been full of things that were interesting to you?” (all the time, most of the time, a good bit of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, none of the time) | ||

| Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale41 | Morale | “Things keep getting worse as I get older” |

| “I am as happy now as when I was younger” (yes, no) | ||

| Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness42 | Happiness | “In the past months have you been feeling on top of the world?” |

| “As I look back on my life, I am fairly well satisfied” (yes, no, don’t know) |

Measurement of wellness

As a result of the varied way that wellness has been defined and understood, a variety of wellness measures exist. Consistent with the characteristics of wellness described, a wellness measure should reflect the multidimensionality and systems orientation of the concept and have a salutogenic focus. In the literature, as well as in daily practice, clinical, physiological, behavioral, and perceptual indicators are all touted as wellness measures. Clinical measures include serum cholesterol level and blood pressure, physiological indicators include skinfold measurements and maximum oxygen uptake, behavioral measures include smoking status and physical activity frequency, and perceptual measures include patient/client self-assessment tools such as global indicators of health status (“Compared with other people your age, would you say your health is excellent, good, fair, or poor?”)30 and the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Status Questionnaire31 (see Table 2-3).

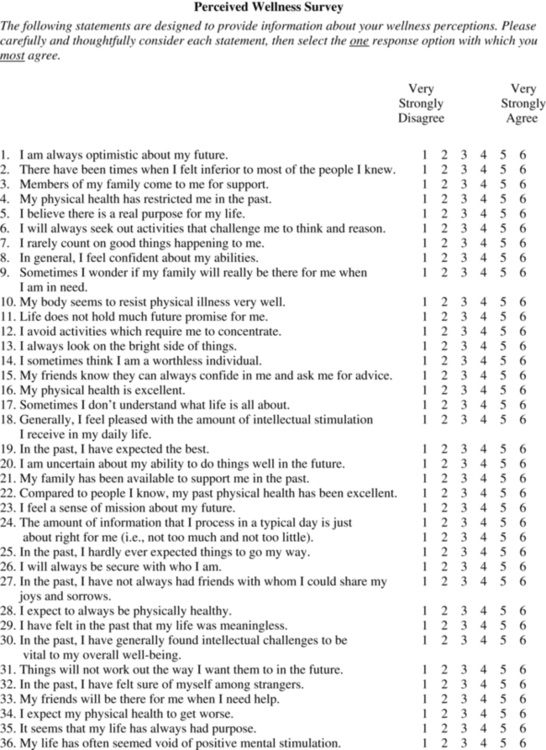

Although some perceptual measures assess only single system status (e.g., psychological well-being, mental well-being), numerous multidimensional perceptual measures exist that can serve as wellness measures. Perceptual constructs that have been used as wellness measures include general health status,31 subjective well-being,31,32 general well-being,33,34 morale,35,36 happiness,37,38 life satisfaction,39–41 hardiness,42,43 and perceived wellness18,44,45 (see Table 2-3). Refer to Figure 2-3 for the “Perceived Wellness Survey” used by many professionals to help conceptualize the client’s perception of her or his wellness. This survey was first published in the American Journal of Health Promotion in 1997.18

The Perceived Wellness Survey.18

The Perceived Wellness Survey.18Physical therapists assess perceptions as a part of the patient/client history, as recommended in the “Guide to Physical Therapist Practice.”46 Occupational therapists assess perceptions as part of their focus on human performance and occupation. Some of the kinds of perceptions that can be assessed include perceptions of general health status, social support systems, role and social functioning, self-efficacy, and functional status in self-care and home management activities and work, community, and leisure activities. Although a few of these categories are included in overall wellness, such as general health status and social and role functioning, measuring wellness perceptions specifically can provide additional and more complete information about the patient that both the physical and occupational therapist can use to formulate a plan that can be insightful to the patient/client. Therefore perceptual tools should be used when measuring wellness.

Merging wellness into rehabilitation

Incorporating wellness into rehabilitation requires that the therapist or provider modify the traditional approach used to treat patients, which involves changing the focus from illness to wellness, being a role model of wellness, incorporating wellness measures into the examination, considering the client within his or her system, and offering services beyond the traditional patient-provider relationship. Establishing a wellness approach also requires that the provider assume the role of a facilitator or partner rather than that of an authority figure.47

When a patient is ill, it is often appropriate for the health care provider to act as the expert because the patient has limited ability to provide self-care and is relying on the provider for information and skills to recover and improve. In a wellness paradigm the best approach is to believe that the client knows best in terms of maximizing her or his potential; therefore assuming a partner or facilitator role is more appropriate and will create a relationship in which the client feels empowered to take control. Rather than “making” the client well, the provider can view the client as a whole person within a biopsychosocial context and partner with the client to discover the most appropriate path to achieve wellness. This approach is consistent with a client-centered perspective, in comparison to a biomedical approach in which the emphasis is on impairment and activity limitations.48–50 Recent discussions in the literature by a variety of health care providers suggest there is an important role for a client-centered approach within traditional medical settings.48–52 Client-centered care requires the following:

Assessment of and consideration for client thoughts, feelings, and expectations

Assessment of and consideration for client thoughts, feelings, and expectations

Education about the client’s condition to enhance the client’s ability to take responsibility for her or his own well-being

Education about the client’s condition to enhance the client’s ability to take responsibility for her or his own well-being

A shift in professional identity from expert advisor to partner and facilitator

A shift in professional identity from expert advisor to partner and facilitator

Excellent communication skills, including the use of language the client can understand and effective listening skills

Excellent communication skills, including the use of language the client can understand and effective listening skills

Providers who have a high level of confidence in their knowledge and skill to guide clients to optimize their potential (e.g., achieve greater wellness)49,50

Providers who have a high level of confidence in their knowledge and skill to guide clients to optimize their potential (e.g., achieve greater wellness)49,50

Providers who are role models and who assume the role of facilitator, which will establish a relationship and an environment in which clients can attain greater wellness

Providers who are role models and who assume the role of facilitator, which will establish a relationship and an environment in which clients can attain greater wellness

Because individuals without overt disease are typically unmotivated to seek professional assistance, consideration must be given to how a provider recruits those without disease. A focus on wellness and health-causing activities is a powerful solution to this dilemma. In a sports or athletic context, this approach would be considered “performance enhancing” and would be marketed to individuals who have goals and ambitions related to improving athletic performance in a specific context (e.g., improving 10K time, increasing cycling distance or speed). In a general wellness context, an appropriate marketing message might be to improve quality of life or productivity, or any subjective measure that a client deems important. The same knowledge and skills therapists use when intervening to prevent injury, delay or prevent the progression of disease, or enhance quality of movement are useful in a primary prevention context in which the goal is to improve quality of life, well-being, and productivity. The difference is the context in which the knowledge and skills are applied. Adopting a wellness paradigm and a client-centered perspective or focus creates an environment surrounding the client-provider relationship that both empowers the client to make meaningful changes and establishes a partnership that is most conducive to change and improvement. The improvement of quality of life or wellness requires a consideration of the client as a whole person, by definition, as discussed previously in this chapter. Using a client-centered, whole-person approach to the design of an intervention program requires a considerably different approach than the traditional, biomedical approach of measuring clinical and behavioral variables to identify impairments and functional loss and creating an intervention aimed at ameliorating the impairment.49,50 Suddenly clients are more than their diseases, which sends a much different message and creates a much different relationship between the provider and the client.

Applying this same approach to individuals with chronic health conditions implies that the therapist must attend to more than just impairments and activity limitations and their causes when designing intervention programs and determining the best approach to adopt with an individual client. It requires consideration of issues such as social support given and received, intellectual curiosity, physical self-esteem, general self-esteem, optimism, and so forth. Recognition of these dimensions of the individual provides a unique opportunity to keep the client at the focus of the intervention and design interventions in partnership with the client that will stand a greater chance of producing positive, meaningful outcomes.49 The following examples attempt to illustrate the adoption and application of a wellness paradigm within neurorehabilitation.