Chapter 17 Headaches and migraines

Introduction

Headache is the most prevalent neurological symptom encountered in medical practice.1 It is experienced by almost everyone at some stage of their lives. Headache can be a symptom of a serious life-threatening disease, such as a brain tumour, although in most cases it is a benign disorder that can comprise a primary headache, such as a migraine, or a tension-type headache.2 Nevertheless, migraines and tension-type headaches can cause considerable levels of disability, not only to patients and their families but also to society as a whole owing to its high prevalence in the general population.

There is a significant burden associated with headache and it is a major public health problem.2 The most common types of headaches are migraines and tension headaches. Globally, the percentage of the adult population with an active headache disorder is 47% for headaches in general, 10% for migraine, 38% for tension-type headaches, and 3% for chronic headaches that last for more than 15 days per month.2, 3

General lifestyle and behavioural interventions

Numerous lifestyle factors can trigger headaches. These can be caused by lifestyle stressors, particular foods and beverages, sleep problems, sinus and allergy problems, muscle tension, and mood disorders.4 People who report having relatives who get migraine headaches are more likely to get them as well.4

Health practitioners are ideally placed to treat most patients with chronic headaches and migraines. Once organic causes are excluded, management needs to focus on lifestyle and dietary changes to help prevent and promote self-management of headaches and migraines. A multi-disciplinary approach may be required till the exact causes are identified. This was demonstrated in a recent study where 80 men and women with migraine were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. The intervention group consisted of supervised exercise therapy, stress management and relaxation therapy lectures, dietary lecture, and massage therapy sessions.5 The control group consisted of standard care with the patient’s family clinician. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups before intervention. At the end of the 6-week intervention and at a 3-month follow-up, the intervention group experienced statistically significant improvement in pain frequency, pain intensity and duration, described better quality of life and health status and reduced symptoms of depression. Healthy behaviour patterns involving relaxation practice and lifestyle modifications of diet, regular meals, exercise, and correcting sleep deprivation consistently demonstrate significant improvement in reducing headaches and migraines and improved mood levels.5

Mind–body therapies

Stress management, biofeedback, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)

Chronic tension and mixed type headaches appear to benefit from mind–body interventions, especially where the evidence for mind–body therapies is quite strong such as migraine headaches.6 Several clinical trials for chronic tension-type headaches and chronic migraines have found that relaxation training significantly reduced headache activity compared to talk therapy, self-monitoring, muscle relaxant (chlormezanone), information/education, and no treatment.7–14 Penzien and colleagues estimate that behavioural interventions yielded approximately 35–50% reduction in migraine and tension-type headaches.13

Relaxation therapies have been described to be as effective, or more effective, in reducing the frequency of migraine headaches comparable to pharmacologic medication.14 This review investigated the evidence for mind–body therapies for chronic pain disorders including chronic headaches and migraines. Based on evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews of the literature, relaxation and thermal biofeedback were deemed effective treatments for recurrent migraine while relaxation and muscle biofeedback was an effective adjunct or stand alone therapy for recurrent tension headaches.14 The physiological basis for their effectiveness is unclear, but data from 1 trial suggest that levels of plasma beta-endorphin can be altered by relaxation and biofeedback therapies.15

Children appear to be very responsive to mind–body related therapies. An early systematic review of 7 relaxation trials and 5 biofeedback-assisted relaxation trials examined a total of 252 children with headaches.16 Overall relaxation training was better than an information-giving intervention, a discussion group, or treatment with propranolol 3mg/kg/day, including at 5–6 month follow-up. Relaxation training together with biofeedback experienced greater reduction in headache frequency, intensity and duration than the control group, post-treatment and at 6-month follow-up. A more recent Cochrane review identified 28 RCTs and concluded that:

there was very good evidence that psychological treatments, principally relaxation and cognitive behavioural therapy, were effective in reducing the severity and frequency of chronic headache in children and adolescents.17

In summary, mind–body therapies may be more effective in treating headaches compared to no treatment or in combination with standard care. However, when compared to each other, there may not be a significant difference. A systematic review of autogenic relaxation training reported equivalency among several different relaxation techniques in the treatment of headaches.18 Mind–body interventions for migraine have been better studied than those for tension headache. The US Headache Consortium treatment guidelines for migraines now include cognitive and behavioural treatment recommendations based on evidence from 39 controlled trials.19, 20 It suggests that relaxation training, thermal biofeedback combined with relaxation training, electromyographic biofeedback, and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may be considered as treatment options for prevention of migraine and combined with preventive drug therapy to achieve additional clinical improvement for migraine relief based on the highest level I evidence rating. Furthermore, a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of the literature assessed 29 randomised control studies (1432 patients) and found children and adolescents who suffer chronic headaches significantly benefit from psychological therapies — namely relaxation, hypnosis, coping skills, biofeedback and CBT — and concluded there is a strong case to include these therapies as routine care.17

Sleep

Sleep disturbance is implicated with specific headache patterns and severity.21, 22 In a recent study it was reported that a short sleep group, who routinely slept 6 hours per night, exhibited the more severe headache patterns and more sleep-related headache compared with those who slept longer.23 Also sleep complaints occurred with greater frequency among chronic than episodic migraine sufferers.24 A study of 49 men and women from headache clinics with onset of headache during the night or early morning, were investigated.25 Fifty-five percent were found to have specific sleep disorders. Also participants were found to have excessive daytime somnolence. After treatment for defined sleep disorders, all participants reported improvement or absence of their headache (65%). All patients who reported sleep apnoea found that their headaches disappeared with appropriate treatment.25 Assessing patients for sleep disorders may be important in the management of patients with chronic headaches.

Environmental factors

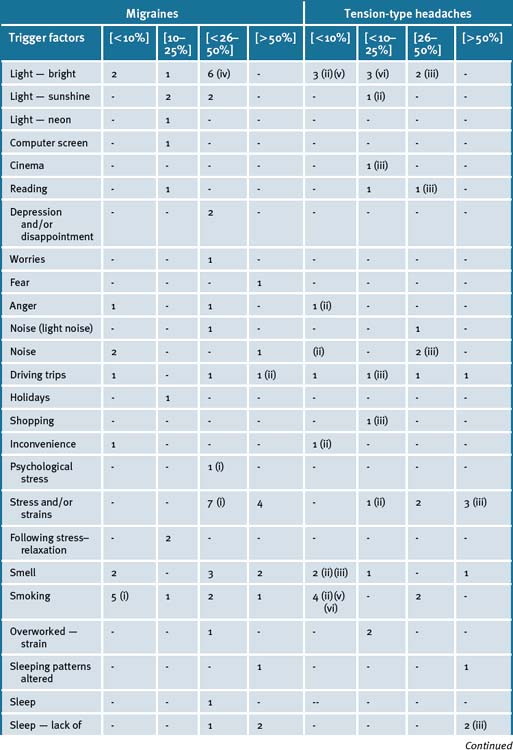

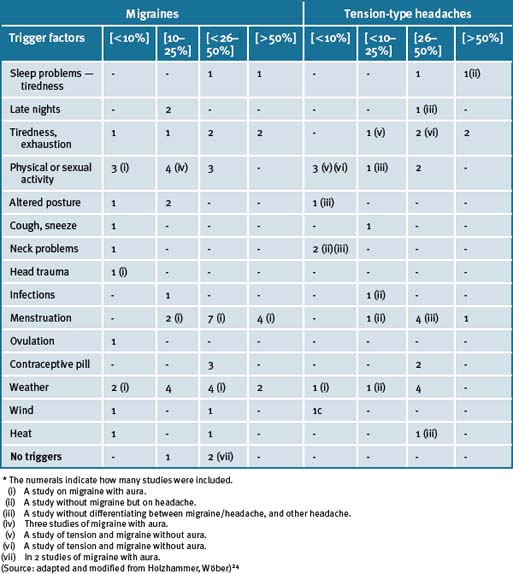

In a recent study it was reported that from a cohort of 120 participants the most common trigger factors that were associated with precipitating a migraine or tension-type headache were the weather (82.5%), stress (66.7%) and menstruation (51.4%).23 There have been numerous factors that have been implicated with triggering migraines and tension-type headaches not related to diet (Table 17.1).24 In a further study it was reported that there are precipitating and aggravating factors differentiating migraine from tension-type headache but not vice versa.25 Three of the migraine-specific precipitating factors were the weather, smell, and smoke which involved the nose and sinus system, suggesting a greater significance of this system in headache causation than is generally considered.25

Table 17.1 Non-alimentary trigger factors for migraines and tension-type headaches (4 frequency ranges)∗

A recent US study of over 7000 people diagnosed with headache identified frequency and severity of headaches and hospital admission increased with climacteric changes namely, higher ambient temperatures and to a lesser extent lower barometric air pressure, but not air pollution.26

In addition, people who tend to spend a lot of time indoors may suffer chronic headaches due to environmental toxins, such as volatile organic compounds released from new furniture and renovations, and poor air quality.27, 28 Airing the house or workplace frequently and spending more time outdoors is helpful. Other known environmental factors which have been implicated as possible causes of migraines and headaches include: cigarette smoking; perfumes; watching excessive television; bright lights; loud noises; working in front of TV/VCR/computer screens; and medications, such as the oral contraceptive pill.23, 24, 29

Physical activity

An 8-month RCT evaluated the effectiveness of a workplace educational and physical program in reducing headache, neck and shoulder pain.30 In the study, 192 employees participated, using diaries for the daily recording of pain episodes. Compared with baseline, those randomised to education and physical exercise program, there was significant reduction in headache frequency, frequency of neck and shoulder pain and reduced analgesic drug consumption compared with the control group. The study suggests that an educational and physical program reduces headache and neck and shoulder pain in a working community.

Nutritional influences

Diet

Over a quarter of patients with migraines recognise hypoglycaemia, caffeine withdrawal and certain foods as migraine triggers.31–34 Such triggers can include monosodium glutamate (also labelled as hydrolysed yeast extract, natural flavouring, hydrolysed vegetable protein), that is often found in soups and Chinese food. Nitrites (a preservative found in numerous meats and hot dog products), tyramines (found in wines and aged foods such as cheeses), and phenylethylamine (found in chocolate, garlic, nuts, raw onions, and seeds) comprise other potential migraine triggers. Any type of alcohol, artificial sweeteners, citrus fruits, pickled products, and vinegars are additional possible triggers. It should be noted that not everyone will have all of these foods as triggers, so a diet totally eliminating these items may not be warranted in all those suffering from migraines or headaches.

A study emphasised the need to explore diet in the precipitation of headaches in children and adolescents with migraine.33

The risk-associated foods that have been listed include cheeses, chocolate, citrus fruits, hot dogs, monosodium glutamate, aspartame, fatty foods, ice cream, caffeine withdrawal, and alcoholic drinks, especially red wine and beer, as potential precipitants.34 A large-scale study of 577 patients with migraines found a definite statistical association between sensitivity to cheese/chocolate, red wine, beer but not to alcohol in general.35 Tyramine, phenylethylamine, histamine, nitrites and sulphites are involved in the mechanism of food intolerance headache, by influencing the release of serotonin and noradrenalin, causing vasoconstriction or vasodilatation, or by direct stimulation of trigeminal ganglia, brainstem, and cortical neuronal pathways.36 This study found 93% of 88 children with severe frequent migraine recovered on oligo-antigenic diets, with recurrence of migraines after reintroduction of the suspected foods, suggesting an allergenic, not idiosyncratic, response. Associated symptoms which improved in addition to headache included abdominal pain, behaviour disorder, fits, asthma, and eczema. Patients who developed migraines by non-specific factors, such as blows to the head, exercise, and flashing lights, no longer experienced migraines while they were on the diet.

A later study by the same group demonstrated similar findings on 45 children with migraines and epilepsy.37 The oligo-antigenic diet alleviated most symptoms of migraines, abdominal pains, hyperkinetic behaviour and epilepsy.

However, an evaluation of the scientific evidence of 13 oral challenge tests to dietary biogenic amines in susceptible patients38 found no relation with migraines, some of the studies were poorly designed and more research is required to support this association.

Patients with headaches, abdominal symptoms and/or obscure neurologic dysfunction such as ataxia may warrant testing for anti-gliadin antibodies.39

Caffeine consumption and withdrawal are also known causes of headaches and migraines and, thus, caffeine is best minimised or avoided.40 If consuming caffeine, increasing water intake helps as dehydration from caffeine may also contribute to headaches and migraines.41

Nutritional supplements

Riboflavin (vitamin B2)

For many migraine sufferers, taking riboflavin regularly may help decrease the frequency and shorten the duration of migraine headaches. Several studies have demonstrated benefits of riboflavin supplement as a prophylactic in reducing migraine frequency. A pilot trial followed up with a randomised placebo-controlled trial by the same group found patients taking a daily dose of 400mgs riboflavin were significantly better for migraine prophylaxis over placebo.44, 45 The number of days with migraine was halved in approximately 60% of the participants taking riboflavin compared with 15% in placebo group.45 A more recent study of 23 patients also demonstrated a reduction of headache frequency by 50% from an average of 4 days a month to 2 days following 3–6 months of treatment with 400mgs of riboflavin daily.46

Magnesium (Mg++)

Magnesium deficiency

It has been reported that studies of low-brain magnesium have been associated with migraine sufferers.47 Hence magnesium supplementation may play a role in the prophylaxis and treatment of migraines. Magnesium deficiency is reported in some studies of migraine sufferers and is suspected in promoting muscle irritability and sensitivity during migraine attacks.48, 49 Reduced intracellular free magnesium in the brain and body tissues of migraine sufferers may cause instability of neuronal function and thus increasing the risk of developing an attack.50

Recent review of the literature suggest deficiencies in magnesium play a role in the pathogenesis of migraine headaches that the use of intravenous and oral magnesium could provide a simple, inexpensive, safe option for acute and preventative treatment.51

Oral magnesium

The first RCT of Mg++ for migraine prevention involved only 20 participants and was positive. The active therapy was 360mg Mg++ pyrrolidone carboxylic acid divided TDS.52 A further, earlier, RCT of 81 migraine patients, who were randomised to receive either 600mg/day of magnesium or placebo for 12 weeks, demonstrated that by 9–12 weeks there was significant reduction in frequency and duration of migraine attacks, and reduction in medication use.53 Magnesium daily intake demonstrated a 41.6% improvement versus 15.8% for placebo. In a further double-blind placebo-controlled trial designed for migraine prophylaxis involving 69 participants taking 486mg Mg++ there was no benefit for Mg++ observed at the end of the 3-month treatment phase.54 The positive responser rate was 28.6% in the magnesium group and 29.4% in placebo subjects with respect to the primary efficacy endpoint. Diarrhoea was reported in significant numbers of both patients receiving placebo (23.5%) and double the risk in patients receiving magnesium (45.7%). The high rate in the active arms suggests that a poorly absorbed magnesium preparation added to the negative outcome.54, 55

In a placebo-controlled RCT with children and adolescents aged 3 to 17 years, magnesium oxide was administered at a dose of 9mg/kg divided TID.56 Approximately three-quarters of the eligible participants completed the study, with a significant decrease in trend in headache days in the active treatment group versus placebo. However, given the small participant numbers this study did not unequivocally determine whether oral magnesium oxide was or was not superior to placebo in preventing frequent migrainous headache in children.

Reports that debate the conflicting data from migraine treatments of patients as either being likely to respond (low levels) or unlikely to respond (normal levels) allude to the notion that low levels of intracellular Mg++ ion and serum ionised Mg++ may correlate with the element’s efficacy.57, 58, 59

In a study designed to determine Mg++ effects on sumatriptan non-responders (83% of who had low ionised Mg++ levels), Cady and colleagues found that although ionised Mg++ levels could be normalised intravenously; a daily dose of 250mg of oral magnesium taurate for 5.5 months failed to maintain normal levels.60 It was recommended that a daily dose of 600mg of chelated or slow-release oral Mg++ be employed for sustained supplementation.61

IV magnesium

A number of trials indicate IV magnesium may play a valid role in the acute treatment of severe migraine, especially in a hospital setting. The use of IV magnesium sulfate has been explored for treatment of acute severe migraine attacks but caution and further research is required with its potential use.61

A recent single-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 30 patients, with acute moderate or severe migraine attacks, were randomised to receive 1g intravenous magnesium sulfate (given over 15 minutes) or 10 mL of 0.9% saline intravenously.62 Those in the placebo group with persisting complaints of pain or nausea and vomiting after 30 minutes also received 1g magnesium sulfate intravenously. All patients in the treatment group responded to treatment with magnesium sulfate with significant reduction in pain in up to 87% of patients and all patients (100%), accompanying symptoms disappeared. Symptoms persisted in the placebo group, such as nausea, irritability or photophobia, who then responded to the IV magnesium treatment causing symptoms to completely disappear. The authors concluded that 1g intravenous magnesium sulfate is an efficient, safe, and well-tolerated drug in the treatment of migraine attacks.62

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

A recent, not dose-ranging, RCT study reported the use of CoQ10 involving 42 participants given either a non-commercially available liquid formulation of water-dispersed nano-particles comprising a super-cooled melt of CoQ10 with modified physicochemical properties taken 300mg/day divided TID or placebo.63 Migraine attack frequency in month 4 was reduced ≥50% in 47.6% of patients in the active arm (i.e. those taking CoQ10)as compared to 14.4% for placebo. Adverse events were not statistically different between the 2 treatment groups. One participant who was in the treatment group withdrew and was not considered in the analysis due to a cutaneous allergy to CoQ10.

In a recent study of CoQ10 deficiency and response to supplementation in paediatric and adolescent migraine it was suggested that determination of deficiency and subsequent supplementation may result in clinical improvement.64 However further analysis involving more scientifically rigorous methodology is required.

Fish oils

A well-performed double-blind, cross-over study consisting of a 2-month period on fish oil supplementation, 1 month wash-out period, and 2 months of placebo (olive oil), demonstrated significant reduction in duration and severity of headaches in adolescents with recurrent migraines in both the treatment and placebo group.65 The authors concluded that the marked benefit in both groups compared with baseline was beyond a placebo effect and suggested that olive oil may also demonstrate benefit for recurrent migraines.65

Herbal medicines

Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium)

Feverfew is a popular herbal remedy recommended for the prevention of migraine.

There have been some positive trials, such as a positive trial showing efficacy for feverfew in migraine sufferers66 and a positive trial using feverfew CO2 extract (MIG-99, 6.25mg TID).67 A reduction in headache attacks per month was reported during the second and third recording periods (from 4.8 attacks to 2.9 with MIG-99 versus 3.5 attacks with placebo [a reduction in attacks per month of 1.9 versus 1.3]) (P = 046, and OR 3.4).67 Greater than 50% reduction in headache attacks per 28 days occurred in 30.3% of the feverfew treatment group and 17.3% of the placebo arm, a therapeutic gain of 13% (P = 047). Adverse events occurred in 8.4% of the participants receiving feverfew and 10.2% of placebo controls.

However, the totality of evidence, including systematic reviews, does not support feverfew as representing an unequivocally effective therapy for migraine, nor has its safety with long-term use been established. One systematic review68 of feverfew showed potential for prophylaxis against migraine attacks, however a more recent Cochrane review69 of all the literature found most trials lacked methodological quality and its efficacy was concluded not to have been established. Adequate long-term studies, including extension safety trials, are warranted.

A RCT study to determine the efficacy for migraine prophylaxis of a compound containing a combination of riboflavin, magnesium, and feverfew was recently completed.70 The combination compound provided a daily dose of riboflavin 400mg, magnesium 300mg, and feverfew 100mg. The placebo contained 25mg riboflavin alone. The study documented that 49 participants completed the 3-month trial. For the primary outcome measure, a 50% or greater reduction in migraines was observed, however, there was no difference between active and placebo (riboflavin) group, achieved by 10 (42%) and 11 (44%) participants respectively. Similarly, there was no significant difference in secondary outcome measures, for active versus placebo groups, respectively. Also, no change in mean number of migraines, migraine days, migraine index, or triptan doses was observed. Compared to baseline, however, both groups showed a significant reduction in number of migraines, migraine days, and migraine index.70 It was concluded that riboflavin (25mg) showed an effect comparable to a combination of riboflavin (400mg), magnesium (300mg), and feverfew (100mg).

Physical therapies

Musculoskeletal manipulation

Non-invasive physical treatments are often used to treat common types of chronic/recurrent headache. Cervicogenic headaches are well documented and respond well to daily walking to develop better postural alignment, stretching, and physical therapies, such as manipulation.71 Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) appears to have a better effect than massage for cervicogenic headache. It also appears that SMT has an effect comparable to commonly used first-line prophylactic prescription medication for tension-type headache and migraine headache. This conclusion emerged from several trials of adequate methodological quality.71

A recent Cochrane review of 22 studies with a total of 2628 patients (age 12 to 78 years) met the inclusion criteria.72 Five types of headache were studied namely — migraine, tension-type, cervicogenic, a mix of migraine and tension-type, and post-traumatic headache. It was reported that a few non-invasive physical treatments may be effective as prophylactic treatments for chronic/recurrent headaches. Based on trial results, these treatments appear to be associated with little risk of serious adverse effects.72 The authors concluded the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-invasive physical treatments require further research using scientifically rigorous methods as there was significant heterogeneity of the studies included in the review.

Despite these positive findings, a more recent systematic review looked at the role for cervical musculoskeletal dysfunction in migraine and based on the evidence the review found that there is currently no convincing evidence to confirm this phenomenon in humans.73

Acupuncture

A recent general practice study that investigated 400 patients with chronic headache and migraine found acupuncture to be significantly effective.74 Patients were randomised to 12 sessions of acupuncture treatment or standard medical care. Acupuncture treatment led to 34% reduction in headache severity, 15% less medication use, 25% fewer visits to GPs and 22 fewer days of headache a year compared with 16% reduction in headache severity in patients given standard care at 1-year follow-up. The acupuncture treatment appeared long-lasting.74

A critical review reported its findings from 13 clinical trials and agreed with previous literature reviews that the majority of studies of acupuncture for migraine research were of a poor quality, with conflicting results,75 noting that large high-quality trials were required.

Recently a number of additional conflicting studies have been conducted on the use of acupuncture to treat and prevent headaches.76–80 Nevertheless acupuncture has been increasingly advocated and used in Western countries for migraine treatment, but the evidence of its effectiveness remains weak. A large variability of treatments is present in published studies and no acu-point selection according to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has ever been investigated so far. Therefore, the low level of evidence of acupuncture effectiveness might partly have depended on the inappropriate treatments that have been investigated in the most recent past.76, 77 In 1 trial, acupuncture was reported to be no more effective than sham acupuncture in reducing migraine headaches although both interventions were more effective than a waiting list control.76 The effectiveness of a true acupuncture treatment according to TCM in migraine without aura, comparing it to a standard mock acupuncture protocol, an accurate mock acupuncture healing ritual, and untreated controls, has demonstrated significant efficacy.78, 79, 80

Idiopathic headache

A Cochrane review81 of 26 trials including a total of 1151 patients concluded that the existing evidence supported the value of acupuncture for the treatment of idiopathic headaches. However, the quality and amount of evidence was not fully convincing.

Chronic-tension headache

A recent Cochrane review of the literature including 11 trials of 2317 participants (mean age 62 years) found overall statistically significant benefits over control for chronic-tension headache (reduction in number of days and pain intensity) in 2 large major trials, but only small benefits when compared with sham acupuncture in 5 smaller trials.82

Migraine prophylaxis

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis of the literature identified 22 trials inclusive of 4419 participants and found overall 14 trials comparing ‘true’ acupuncture with sham acupuncture, and there were no statistically significant differences, but in 4 trials acupuncture was superior to proven prophylactic drug treatment, associated with slightly better outcomes and fewer adverse effects in the acupuncture group. The authors concluded the ‘evidence in support of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis was considered promising but insufficient …’ and ‘… should be considered a treatment option for patients willing to undergo this treatment’.83

Conclusion

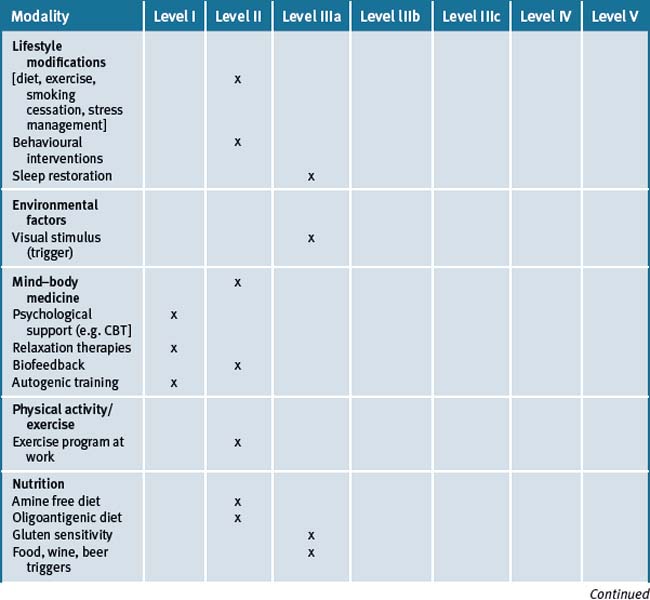

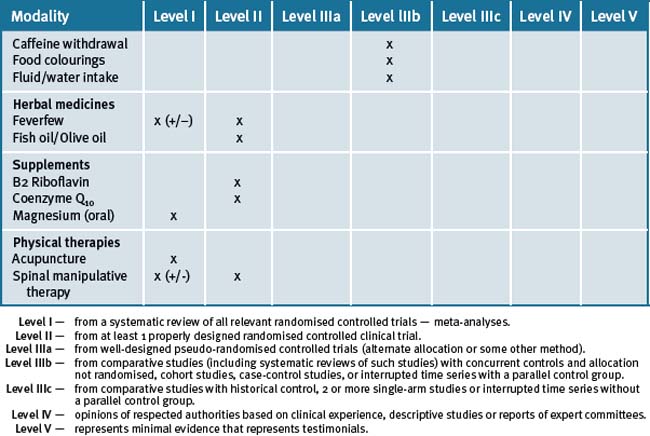

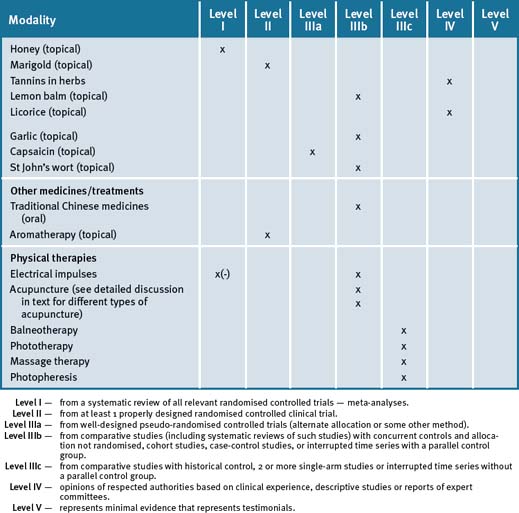

The overall evidence for integrative and complementary therapies is summarised in Table 17.2. Lifestyle, exercise, relaxation and psychological therapies, as well as dietary factors, play an important role in the management of headache and migraine. With respect to supplements, there currently is at best level II evidence for most of the supplement compounds discussed in this chapter. Level II evidence represents limited evidence from a single randomised trial, or non-randomised trials or multiple trials with inconsistent outcomes. No firm consensus yet exists as to the relative treatment efficacy of these multiple agents, but given the number of patients, data consistency, or lack thereof, we tentatively suggest that the rank order may be of the order of — Mg++ > feverfew > riboflavin > CoQ10. At present, TCM-based acupuncture may offer the best modality of its kind for the treatment of migraines and headaches.

Clinical tips handout for patients — migraines and headaches

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine (most helpful)

4 Dietary changes

Avoid

5 Environment

7 Supplements

Vitamins

Riboflavin, vitamin B2

Pro-vitamin

Coenzyme Q10

Minerals

Magnesium oxide and calcium (best provided together)

Fish oils

1 Andlin-Sobocki P., Jönsson B., Wittchen H.U., et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:1-27.

2 Jensen R., Stovner L.J. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):354-361.

3 Speciali J.G., Eckeli A.L., Dach F. Tension-type headache. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(5):839-853.

4 Sierpina V., Astin J., Giordano J. Mind–body therapies for headache. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(10):1518-1522.

5 Hoodin F., Brines B.J., Lake A.E.III, et al. Behavioural self-management in an inpatient headache treatment unit: increasing adherence and relationship to changes in affective distress. Headache. 2000;40(5):377-383.

6 Wahbeh H., Elsas S.M., Oken B.S. Mind–body interventions: applications in neurology. Neurology. 2008;70(24):2321-2328.

7 Fumal A., Schoenen J. Tension-type headache: current research and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(1):70-83.

8 Holroyd K.A., Penzien D.B. Client variables and behavioural treatment of recurrent tension headaches: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 1986;9:515-536.

9 Holroyd K.A., Martin P.R. Psychological treatments for tension-type headache. In: Olesen J., Tfelt-Hansen P., editors. Welch KMA. The Headaches. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: ).Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:643-649.

10 Blanchard E.B., Appelbaum K.A., Guarnieri P., et al. Two studies of the long-term follow-up of minimal-therapist contact treatments of vascular and tension headache. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:427-432.

11 Schoenen J., Pholien P. Maertens de Noordhout A. EMG biofeedback in tension-type headache: is the 4th session predictive of outcome? Cephalalgia. 1985;5:132-133.

12 Holroyd K.A. Tension-type headache, cluster headache, and miscellaneous headaches: Psychological and behavioural techniques. In: Olesen J., Tfelt-Hansen P., editors. Welch KMA. The Headaches. New York: Raven Press; 1993:515-520.

13 Penzien D.B., Rains J.C., Andrasik F. Behavioural management of recurrent headache: three decades of experience and empiricism. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2002;27(2):163-181.

14 Astin J.A. Mind body therapies for the management of pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:27-32.

15 Helm-Hylkema H., Orlebeke J.F., Enting L.A., et al. Effects of behaviour therapy on migraine and plasma beta-endorphin in young migraine patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1990;15(1):39-45.

16 Duckro P.N., Cantwell-Simmonds E. A review of studies evaluating biofeedback and relaxation training in the management of pediatric headache. Headache. 1989;29:428-433.

17 Eccleston C., Yorke L., Morley S., et al. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2003. CD003968

18 Kanji N., White A.R., Ernst E. Autogenic training for tension type headaches: a systematic review of controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2006;14(2):144-150.

19 http://www.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0089.pdf (accessed July 2008).

20 Goslin R.E., Gray R.N., McCrory D.C., et al. Behavioural and Physical Treatments for Migraine Headache. Technical Review 2.2. February 1999. (Prepared for the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research under Contract No. 290-94-2025. Available from the National Technical Information Service; NTIS Accession No. 127946)

21 Kelman L., Rains J.C. Headache and sleep: examination of sleep patterns and complaints in a large clinical sample of migraineurs. Headache. 2005;45:904-910.

22 Paiva T., Farinha A., Martins A., et al. Chronic headaches and sleep disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(15):1701-1705.

23 Wöber C., Holzhammer J., Zeitlhofer J., et al. Trigger factors of migraine and tension-type headache: experience and knowledge of the patients. J Headache Pain. 2006;7(4):188-195.

24 Holzhammer J., Wöber C. Non-alimentary trigger factors of migraine and tension-type headache. Schmerz. 2006;20(3):226-237.

25 Spierings E.L., Ranke A.H., Honkoop P.C. Precipitating and aggravating factors of migraine versus tension-type headache. Headache. 2001;41(6):554-558.

26 Phipps R.A. A comparison of two studies reporting the prevalence of the sick building syndrome in New Zealand and England. NZ Med J. 1999;112:228-230.

27 Ando M.. Indoor air and human health–sick house syndrome and multiple chemical sensitivity. Kokuritsu Iyakuhin Shokuhin Eisei Kenkyusho Hokoku. 2002;120:6-38..

28 Mukamal K.J., Wellenius G.A., Suh H.H., et al. Weather and air pollution as triggers of severe headaches. Neurology. 2009;72(10):922-927.

29 Harle D.E., Shepherd A.J., Evans B.J. Visual stimuli are common triggers of migraine and are associated with pattern glare. Headache. 2006;46(9):1431-1440.

30 Mongini F., Ciccone G., Rota E., et al. Effectiveness of an educational and physical programme in reducing headache, neck and shoulder pain: a workplace controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:541-552.

31 Kelman L. The triggers or precipitants of the acute migraine attack. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(5):394-402.

32 Patel R.M., Sarma R., Grimsley E. Popular sweetener sucralose as a migraine trigger. Headache. 2006;46(8):1303-1304.

33 Torelli P., Manzoni G.C. Fasting headache. Correct Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(4):284-291.

34 Millichap J.G., Yee M.M. The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28(1):9-15.

35 Peatfield R.C. Relationships between food, wine and beer-precipitated migrainous headaches. Headache. 1995;35(6):355-357.

36 Egger J., Carter C.M., Wilson J., et al. Is migraine food allergy? A double-blind controlled trial of oligoantigenic diet treatment. Lancet. 1983;2(8355):865-869.

37 Egger J., Carter C.M., Soothill J.F., et al. Oligoantigenic diet treatment of children with epilepsy and migraine. J Pediatr. 1989;114(1):51-58.

38 Jansen S.C., van Dusseldorp M., Bottema K.C., et al. Intolerance to dietary biogenic amines: a review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91(3):233-240.

39 Hadjivassiliou M., Grunewald R.A., Lawden M., et al. Headache in CNS white matter abnormalities associated with gluten sensitivity. Neurol. 2001;56:385-388.

40 Mueller L.L. Diagnosing and managing migraine headache. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 107(10 Suppl. 6), 2007. ES10–6

41 Silverman K., Evans S.M., Strain E.C., et al. Withdrawal syndrome after the double-blind cessation of caffeine consumption. NEJM. 1992;327(16):1109-1114.

42 Maughan R.J. Impact of mild dehydration on wellness and on exercise performance. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(Suppl 2):S19-S23.

43 Spigt M.G., Kuijper E.C., Schayck C.P., et al. Increasing the daily water intake for the prophylactic treatment of headache: a pilot trial. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(9):715-718.

44 Schoenen J., Lenaerts M., Bastings E. High-dose riboflavin as a prophylactic treatment of migraine: results of an open pilot study. Cephalalgia. 1994;14:328-329.

45 Schoenen J., Jacquy J., Lenaerts M. Effectiveness of high-dose riboflavin in migraine prophylaxis. A randomised controlled trial. Neurology. 1998;50:466-470.

46 Boehnke C., Reuter U., Flach U., et al. High-dose riboflavin treatment is efficacious in migraine prophylaxis: an open study in a tertiary care centre. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11(7):475-477.

47 Evans R.W., Taylor F.R. ‘Natural’ or alternative medications for migraine prevention. Headache. 2006;46(6):1012-1018.

48 Thomas J., Tomb E., Thomas E., et al. Migraine treatment by oral magnesium intake and correction of the irritation of buccofacial and cervical muscles as a side effect of mandibular imbalance. Magnes Res. 1994;7(2):123-127.

49 Thomas J., Thomas E., Tomb E. Serum erythrocyte magnesium concentrations and migraine. Magnes Res. 1992;5(2):127-130.

50 Welch K.M., Ramadan N.M. Mitochondria, magnesium and migraine. J Neurol.Sci. 1995;134(1-2):9-14.

51 Sun-Edelstein C., Mauskop A. Role of magnesium in the pathogenesis and treatment of migraine. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009 Mar;9(3):369-379.

52 Facchinetti F., Sances G., Borella P., et al. Magnesium prophylaxis of menstrual migraine: Effects on intracellular magnesium. Headache. 1991;31:298-301.

53 Peikert A., Wilimzig C., Köhne-Volland R. Prophylaxis of migraine with oral magnesium- results from a prospective multi-center, placebo-controlled and double-blind, randomised study. Cephalagia. 1996;16(4):257-263.

54 Pfafferath V., Wessely P., Meyer C., et al. Magnesium in the prophylaxis of migraine—A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 1996;16:436-440.

55 Mauskop A. Editorial: Evidence linking magnesium deficiency to migraines. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:766-767.

56 Wang F., Van Den Eeden S.K., Ackerson L.M., et al. Oral magnesium oxide prophylaxis of frequent migrainous headache in children: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2003;43:601-610.

57 Mazzotta G., Sarchielli P., Alberti A., et al. Intracellular Mg++ concentration and electromyographical ischemic test in juvenile headache. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:802-809.

58 Mauskop A., Altura B.T., Cracco R.Q., et al. Deficiency in serum ionised magnesium but not total magnesium in patients with migraines. Possible role of ICa2+/IMg2+ ratio. Headache. 1993;33:135-138.

59 Mauskop A., Altura B.T., Altura B.M. Serum ionised magnesium in serum ionised calcium/ionised magnesium ratios in women with menstrual migraine. Headache. 2002;42:242-248.

60 Cady R.K., Farmer K., Altura B.T., et al. The effect of magnesium on the responsiveness of migraineurs to a 5-HT1 agonist. Neurology. 1998;50(Suppl 4):A340. Abstract

61 Mauskop A., Altura B.M. Role of magnesium in the pathogenesis and treatment of migraines. Clin Neurosci. 1998;5:24-27.

62 Demirkaya S., Vural O., Dora B., et al. Efficacy of intravenous magnesium sulfate in the treatment of acute migraine attacks. Headache. 2001;41(2):171-177.

63 Sandor P.S., Di Clemente L., Coppola G., et al. Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in migraine prophylaxis: A randomised controlled trial. Neurology. 2005;64:713.

64 Hershey A.D., Powers S.W., Vockell A.L., et al. Coenzyme Q10 deficiency and response to supplementation in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Headache. 2007;47(1):73-80.

65 Harel Z., Gascon G., Riggs S., et al. Supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the management of recurrent migraines in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:154-161.

66 Pfaffenrath V., Diener H.C., Fischer M., et al. The efficacy and safety of Tanacetum parthenium (feverfew) in migraine prophylaxis–a double-blind, multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled dose-response study. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(7):523-532.

67 Diener H.C., Pfaffenrath V., Schnitker J., et al. Efficacy and safety of 6.25mg t.i.d. feverfew CO2-extract (MIG-99) in migraine prevention–a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2005;25(11):1031-1041.

68 Vogler B.K., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Feverfew as a preventive treatment for migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia. 1998;18:704-708.

69 Pittler M.H., Vogler B.K., Ernst E. Feverfew for preventing migraine. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (4):2001.

70 Maisels M., Blumenfeld A., Burchette R. A combination of riboflavin, magnesium, and feverfew for migraine prophylaxis: a randomised trial. Headache. 2004;44(9):885-890.

71 Bronfort G., Assendelft W.J., Evans R., et al. Efficacy of spinal manipulation for chronic headache: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:457-466.

72 Bronfort G., Nilsson N., Haas M., et al. Non-invasive physical treatments for chronic/recurrent headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2004. CD001878

73 Robertson B.A., Morris M.E. The role of cervical dysfunction in migraine:. a systematic review Cephalalgia. 2008;28:474-483.

74 Vickers A.J., Rees R.W., Zollman C.E., et al. Acupuncture for chronic headache in primary care: large, pragmatic, randomised trial. BMJ. 2004;328(7442):744-747.

75 Griggs C., Jensen J. Effectiveness of acupuncture for migraine: critical literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(4):491-501.

76 Linde K., Streng A., Jürgens S., et al. Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomised controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(17):2118-2125.

77 Diener H.C., Kronfeld K., Boewing G., et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of migraine: a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(4):310-316.

78 Linde K., Streng A., Hoppe A., et al. Treatment in a randomised multicenter trial of acupuncture for migraine (ART migraine). Forsch Komplementmed. 2006;13(2):101-108.

79 Alecrim-Andrade J., Maciel-Júnior J.A., Cladellas X.C., et al. Acupuncture in migraine prophylaxis: a randomised sham-controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(5):520-529.

80 Facco E., Liguori A., Petti F., et al. Traditional acupuncture in migraine: a controlled, randomised study. Headache. 2008;48(3):398-407.

81 Melchart D., Linde K., Fischer P., et al. Acupuncture for idiopathic headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2001. CD001218

82 Linde K., Allais G., Brinkhaus B., et al. Acupuncture for tension-type headache. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2009. Art. No.: CD007587. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007587

83 Linde K., Allais G., Brinkhaus B., et al. Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2009. Art. No.: CD001218. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub2