Chapter 9 Headaches

Secondary Headaches, on the other hand, are often manifestations of an underlying serious, sometimes life-threatening, illness. This category includes temporal arteritis, intracranial mass lesions, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri), meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and postconcussion headaches (see head trauma, Chapter 22). Unlike the diagnosis of primary headaches, the diagnosis of secondary headaches typically rests on their clinical context, physical findings, or laboratory abnormalities.

Primary Headaches

Tension-Type Headache

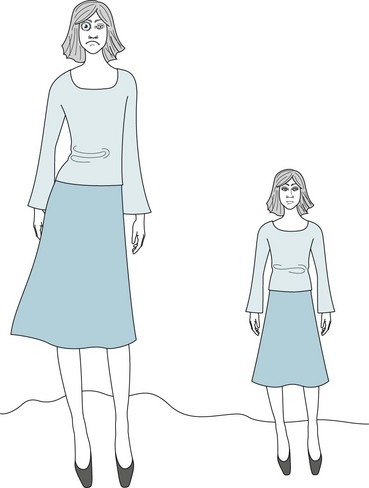

TTH has traditionally been attributed to contraction of the scalp, neck, and face muscles (Fig. 9-1), as well as emotional “tension.” Fatigue, cervical spondylosis, bright light, loud noise, and, at some level, emotional factors allegedly produce or precipitate TTH. However, because studies have demonstrated that this headache results from neither muscle contractions nor psychological tension, the designation “muscle contraction” or “tension” probably represents a misnomer. The term “tension-type” headache is more appropriate. In fact, many neurologists place this headache at the opposite end of a headache spectrum from migraine, where both result from a common, but unknown, physiological disorder.

FIGURE 9-1 Tension-type headaches produce a bandlike, squeezing, symmetric pressure at the neck, temples, or forehead.

Migraine

Neurologists have said, “Whereas tension type headaches are boring in their sameness, migraine headaches are typically rich in symptoms.” In clinical practice, the core criteria for migraine consist of episodic, disabling headaches associated with nausea and photophobia. The nonheadache symptoms, in fact, often overshadow or replace the headache. The headaches’ qualities – throbbing pain and unilateral location – are typical and included in the IHS criteria (Box 9-1).

Box 9-1

Criteria for Migraine*

At least two of the following characteristics:

The headache is accompanied by at least one of the following symptoms:

Migraine with Aura

Migraine with aura, previously labeled classic migraine, affects only about 20–30% of migraine patients. The aura, which can represent almost any symptom of cortex or brain dysfunction, typically precedes or accompanies the headache (Box 9-2). The headache itself is similar to the headache in migraine without an aura (see later).

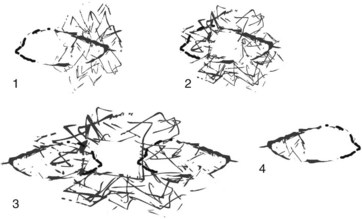

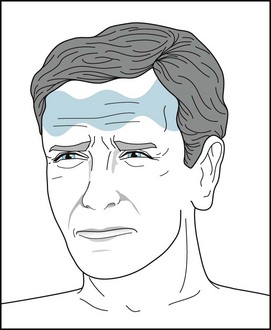

By far the commonest migraine auras are visual hallucinations (see Chapter 12). They usually consist of a graying of a region of the visual field (scotoma) (Fig. 9-2, A), flashing zigzag lines (scintillating or fortification scotomata) (Fig. 9-2, B), crescents of brilliant colors (Fig. 9-2, C), tubular vision, or distortion of objects (metamorphopsia). Unlike visual auras that represent several different neurologic conditions (see Box 12-1), migraine auras most often involve the simultaneous appearance of positive phenomena, such as scintillations, and negative ones, such as opaque areas. Finally, instead of sensory auras, some migraineurs experience premonitory somatic symptoms, such as fatigue, stiff neck, yawning, hunger, and thirst. These patients can frequently predict their impending migraine hours to days before onset.

FIGURE 9-2 A, These drawings by an artist who suffers from migraine show the typical visual obscurations of a scotoma that precedes the headache phase of her migraines. In both cases, she loses a small circular area near the center of vision. As occurs with most migraineurs, she says that, although the aura is only gray and has a simple shape, it mesmerizes her. B, The patient who drew this aura, a scintillating scotoma, wrote, “In the early stages, the area within the lights is somewhat shaded. Later, as the figure widens, you can peer right through the area. Eventually, it gets so wide that it disappears.” This typical scotoma consists of an angular, brightly lit margin and an opaque interior that begins as a star and expands into a crescent. She somehow calculated that it scintillated at 8–12 Hz. Neurologists refer to auras with angular edges as fortification scotomas because of their similarity to ancient military fortresses. C, A 30-year-old woman artist in her first trimester of pregnancy had several migraine headaches that were heralded by this scotoma. Each began as a blue dot and, over 20 minutes, enlarged to a crescent of brightly shimmering, multicolored dots. When the crescent’s intensity peaked, she was so dazzled that she lost her vision and was unable to think clearly. D, Having patients, especially children, draw what they “see” before a headache has great diagnostic value. One adolescent reconstructed this “visual hallucination” using his computer.

Migraine without Aura

Previously labeled common migraine, migraine without aura affects about 75% of migraine patients. In other words, most individuals with migraine do not have an aura. Arising without warning, their headaches are initially throbbing and located predominantly behind a temple (temporal) or around or behind one eye (periorbital or retro-orbital), but usually on only one side of the head (hemicranial) (Fig. 9-3). In the majority of cases, the side of the headache switches within and between attacks. Individual attacks usually occur episodically and last 4–72 hours. Frequent attacks may evolve into a dull, symmetric, and continual pain – chronic daily headache – that mimics TTH.

FIGURE 9-3 Patients with migraine usually have throbbing hemicranial headaches that may either move to the other side of the head or become generalized.

During migraine attacks, patients often have dysphoria and inattentiveness that can mimic depression, complex partial seizures, and other neurologic disturbances (Box 9-3). Most patients withdraw during an attack, but some become feverishly active. Many then tend to drink large quantities of water or crave certain foods or sweets, particularly chocolate. Children often become confused and overactive. After an attack clears, especially when it ends with sleep, migraine sufferers may experience a sense of tranquility or even euphoria.

Box 9-3

Common Neurologic Causes of Transient Mood Disturbance or Altered Mental Status

An additional point of contrast to TTH is that migraine attacks typically begin in the early morning rather than the afternoon. In fact, they often have their onset during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which predominates in the several hours before awakening (see Chapter 17). Sometimes migraines begin exclusively during sleep (nocturnal migraine). No matter when a migraine attack has begun, naturally occurring or medication-induced sleep characteristically cures it.

Psychiatric Comorbidity

TCAs are not only effective for treating migraine comorbid with depression, they are more effective than selective serotonin or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs or SNRIs) for treating migraine with or without comorbid depression. SSRIs and SNRIs are less effective than TCAs, and, when administered concurrently with one of the popular anti-migraine serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5HT]) agonists, such as a “triptan” (see later) or dihydroergotamine (DHE), they carry a low but often-cited risk of producing the serotonin syndrome (see Chapter 6).

Other Subtypes of Migraine

Childhood migraine is not simply migraine in “short adults.” Compared to migraine in adults, in childhood migraine the headache is more severe, but briefer (frequently less than 2 hours), and less likely to be unilateral (only one-third of cases). However, as with migraine in adults, the nonheadache components may overshadow the headache. For example, childhood migraine often produces episodes of confusion, incoherence, or agitation. In addition, it frequently leaves children incapacitated by nausea and vomiting. Physicians caring for children with such episodes may consider mitochondrial encephalopathy as an alternative, although rare, diagnosis (see Chapter 6). Pediatric neurologists also consider mitochondrial encephalopathy, along with hemiplegic migraine (see later), in the differential diagnosis of transient hemiparesis in a child with headaches.

Children are particularly susceptible to migraine variants. In basilar-type migraine, the headache is accompanied or even overshadowed by ataxia, vertigo, dysarthria, or diplopia – symptoms that reflect brain dysfunction in the basilar artery distribution (the cerebellum, brainstem, and posterior cerebrum [see Fig. 11-2]). In addition, when basilar migraine impairs the temporal lobes, children as well as adults may experience temporary generalized memory impairment, e.g., transient global amnesia (see Chapter 11). Hemiplegic migraine, another variant, is defined by hemiparesis of various grades often accompanied by hemiparesthesia, aphasia, or other cortical symptoms. All these symptoms usually precede or occur with an otherwise typical migraine headache, but they may also develop without any headache or other migraine symptom. Thus, in evaluating a patient who has had transient hemiparesis, the physician might consider hemiplegic migraine along with transient ischemic attacks, stroke, postictal (Todd’s) hemiparesis, and conversion disorder.

Migraine-Like Conditions: Food-Induced Headaches

On the other hand, people who miss their customary morning coffee typically develop the caffeine withdrawal syndrome that consists of moderate to severe headache often accompanied by anxiety and depression. Although this syndrome is almost synonymous with coffee deprivation, withdrawal of other caffeine-containing beverages or caffeine-containing medications can precipitate it (see Chapter 17). Herein lies a dilemma: sudden withdrawal of caffeine can cause the withdrawal syndrome, but excessive caffeine leads to irritability, palpitations, and gastric acidity. Moreover, excessive caffeine also is a risk factor for transforming migraine to chronic daily headache.

Acute Treatment

Although opioids may suppress headaches, neurologists have remained wary of their leading to drug-seeking behavior (see Chapter 14). In the majority of patients receiving opioid treatment, emergency room visits and hospitalizations decrease, but their headaches and disability persist. Nevertheless, neurologists often prescribe them in limited, controlled doses when vasoactive or serotoninergic medications carry too many risks, such as for pregnant or elderly patients.

Nausea and vomiting not only constitute symptoms of migraine, but they may also be side effects of DHE or another antimigraine medicine. Whatever their cause or severity, nausea and vomiting prevent gastric absorption of orally administered medicines. Many migraine sufferers thus require a parenterally administered antiemetic, such as metoclopramide (Reglan). One caveat remains: dopamine-blocking antiemetics may cause dystonic reactions identical to those induced by dopamine-blocking antipsychotics (see Chapter 18). Thus, neurologists often prophylactically administer diphenhydramine (Benadryl) along with those antiemetics.

Preventive Treatment

TCAs, particularly amitriptyline and nortriptyline, reduce the severity, frequency, and duration of migraine. Apart from their mood-elevating effect, TCAs may ameliorate migraine because they suppress REM sleep, which is the phase when migraine attacks tend to develop. In addition, because TCAs enhance serotonin, they are analgesic (see Chapter 14). As most migraine patients are young and require only small doses of TCAs compared to those used to treat depression, the side effects of TCAs in this situation are rarely a problem. Interestingly, for preventing migraine, SSRIs are ineffective compared to TCAs.

Neurologists often prescribe β-blockers for migraine prophylaxis, as well as for treatment of essential tremor (see Chapter 18). However, they avoid prescribing β-blockers to migraine patients with comorbid depression because of their tendency to precipitate or exacerbate mood disorders.

Chronic Daily Headache

When patients report headaches, each lasting 4 hours or longer, for at least 15 days each month for at least 3 months, neurologists diagnose chronic daily headache. Patients may arrive at this state via several different routes. For years, they may have had migraine or TTH – to the extent that they can be differentiated (Table 9-1) – that transformed from episodes to a daily or nearly every day affliction. Alternatively, individuals, especially children, develop chronic daily headache after a lifetime of having few, if any, headaches, a situation that neurologists label New Daily Persistent Headache (NDPH). Specific conditions, such as a posttraumatic syndrome or psychiatric disturbances, may also lead or contribute to daily headache. Moreover, whatever the route, overuse of analgesics or other medicines often has paved the way to a chronic daily headache.

| Tension-type | Migraine | |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Bilateral | Hemicranial* |

| Nature | Dull ache | Throbbing* |

| Severity | Slight–moderate | Moderate–severe |

| Associated symptoms | None | Nausea, hyperacusis, photophobia |

| Behavior | Continues working | Seeks seclusion |

| Effect of alcohol | Reduces headache | Worsens headache |

*In approximately half of patients, at least at onset.

In terms of treatment, all of the patient’s physicians must work together to prevent medication overuse and look for underlying psychiatric disorders – some obvious, some not. Injection of botulinum toxin into the head and neck muscles has a therapeutic role (see Chapter 18), and TCAs, valproate, and topiramate may help; however, chronic daily headache generally resists treatment. Nonpharmacologic treatments of this disorder, which are of unproven benefit, include modification of lifestyle, behavior therapy, and elimination of precipitating factors.

Cluster Headaches

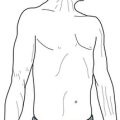

An individual cluster headache consists of searing pain in one eye and its adjacent, periorbital region. Ipsilateral eye tearing, conjunctival injection, nasal congestion, and a partial Horner syndrome (Figs 9-4 and 12-16) typically accompany the pain. Thus, neurologists sometimes classify this headache as trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia. Each headache lasts only 45–90 minutes, but to the patient, the attack seems interminable. The pain’s severity often drives patients to agitation, restlessness, and thoughts of suicide.

FIGURE 9-4 This 43-year-old man with cluster headaches suffers from nightly right-sided unrelenting severe, stabbing unilateral periorbital pain for 45 minutes to 3 hours accompanied by ipsilateral tearing and nasal discharge, along with ptosis and miosis (a partial Horner syndrome). Note that the ptosis prompts compensatory elevation of the eyebrow.

Secondary Headaches

Temporal Arteritis / Giant Cell Arteritis

Because patients are almost always older than 55 years, temporal arteritis is one of the several headache conditions that predominantly affect the elderly (Box 9-4). The headache itself usually consists of dull and continual pain located in one or both temples. Jaw pain on chewing (“jaw claudication”) is frequent and almost pathognomonic. In advanced cases, the temporal arteries are tender and red from induration. Signs of systemic illness, such as malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, low-grade fever, and weight loss, characteristically accompany the headache and reflect the systemic nature of the illness. In fact, polymyalgia rheumatica or another rheumatologic disorder occurs concurrently in about 25% of cases of giant cell arteritis.

Intracranial Mass Lesions

The first symptom of brain tumors and chronic subdural hematomas – common mass lesions (see Chapters 19 and 20) – is most often headaches. However, the headaches’ qualities are nonspecific and potentially misleading. For example, brain tumor headaches usually mimic TTH. Also, when headaches are unilateral, they are on the side opposite the tumor in 20% of cases. Even though brain tumor headaches notoriously begin during early-morning REM sleep and awaken patients, that pattern develops in less than half of cases. Moreover, numerous other headaches display the same early-morning onset, including migraine, cluster, carbon dioxide retention, sleep apnea, and caffeine withdrawal.

Chronic Meningitis

A variety of infectious agents can cause chronic meningitis, but generally only in susceptible individuals. For example, Cryptococcus commonly causes meningitis almost only in patients who have an impaired immune system. With almost any variety of chronic meningitis, CT or MRI typically reveals enlargement of all four ventricles because impaired reabsorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the arachnoid villa leads to communicating hydrocephalus. The CSF pressure is elevated and its analysis shows lymphocytic pleocytosis, low glucose concentration, and elevated protein concentration (see Table 20-1).

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (Pseudotumor Cerebri)

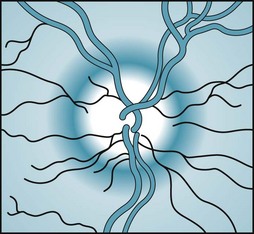

Whatever its etiology, idiopathic intracranial hypertension gives rise, as in so many other conditions, to a dull, generalized headache. This condition’s distinctive feature is papilledema. If untreated, the papilledema leads to an enlarged blind spot within each visual field and eventually blindness from optic atrophy (see Chapter 12). Increased intracranial pressure also sometimes stretches and then damages one or both of the abducens (sixth) cranial nerves. The abducens nerve palsy leads, in turn, to unilateral or bilateral inward eye deviation because of the unopposed, intact third cranial nerves (see Chapter 4).

Bacterial Meningitis, Herpes Encephalitis, and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Bacterial meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage produce commonly occurring, life-threatening illnesses characterized initially by headache. Meningococcus and Pneumococcus, the most common causes of bacterial meningitis, often spread in a small epidemic pattern among children and young adults in confined areas, such as college dormitories and military training camps. In addition, pneumococcal meningitis has a predilection for older, debilitated individuals in whom meningitis and many other infectious illnesses have an insidious onset and subtle signs. Whichever the infectious agent, meningitis usually causes the development, over several hours to several days, of malaise, fever, photophobia, nuchal rigidity, and moderate to severe headache. The headaches are usually generalized, but sometimes they are retro-orbital or nuchal. When physicians suspect bacterial meningitis, they routinely examine the CSF (see Table 20-1) and, if indicated, intravenously administer penicillin or other antibiotic. Vaccinations against meningococcal and pneumococcal infections provide a great deal of protection to students, recruits, and nursing home residents.

Viral infections of the brain (viral encephalitis) also cause headaches. With a few exceptions, these headaches and other symptoms are usually nonspecific and run a more benign course than bacterial infections. However, in contrast to almost all other forms of encephalitis that develop in the United States, herpes simplex encephalitis has distinct clinical features. The virus, herpes simplex, is the most frequent cause of serious, nonepidemic viral encephalitis. It has a remarkable predilection for the frontal inferior surface of the brain and attacks the undersurface of both the frontal and temporal lobes. Like most other viral infections, herpes simplex encephalitis causes fever, somnolence, and delirium. In addition, because the virus attacks the temporal lobes and thus damages the limbic system, it routinely causes complex partial seizures and memory impairment (amnesia). Bilateral temporal lobe damage in some patients may lead to the human variety of the Klüver–Bucy syndrome (see Chapter 16). Frontal and temporal lobe damage may lead to language impairment (aphasia) and frontal lobe behavioral disorders (see Chapter 7). In herpes simplex and other forms of encephalitis, an LP, CT, MRI, and sometimes an electroencephalogram are the most useful diagnostic tests.

Another cause of severe, acutely occurring headache is subarachnoid hemorrhage, which usually results from a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Cerebral artery aneurysms – often shaped like “berries” (berry aneurysms) – usually develop in the arteries comprising the circle of Willis (see Fig. 11-2 and Chapter 20). If the arteries fuse incompletely in utero, weak junctions may eventually form an aneurysm. When an aneurysm ruptures, blood shoots into the subarachnoid space, which surrounds the brainstem and cerebral hemispheres and normally contains crystal-clear CSF. Depending on the aneurysm’s location and size, it may also send a jet of blood into the brain. Beginning almost immediately after a subarachnoid hemorrhage, a CT usually reveals blood in the subarachnoid space. Several hours after the hemorrhage, the CSF color turns from red to yellow (xanthochromic).

MAOIs and the Hypertensive Crisis

MAOIs occasionally react with tyramine-rich foods or a variety of other medicines to cause severe hypertension, excruciating headache, and sometimes a subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage – a hypertensive crisis. This iatrogenic catastrophe, classically associated with MAOI antidepressants, is not peculiar to their use. For example, MAOIs used in Parkinson disease treatment, such as selegiline and rasagiline (see Chapter 18), may cause it. However, the potential for this adverse side effect is low with Parkinson disease medications because they are predominantly MAO-B inhibitors and prescribed at low doses. In contrast, when selegiline is used as an antidepressant (as a patch in Emsam) at doses greater than 12 mg/day, it inhibits MAO-A as well as MAO-B and leaves the patient vulnerable to the reaction.

Cranial Neuralgias

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Of conditions in which pain originates in a cranial nerve – cranial neuralgias – the most clinically important one is trigeminal neuralgia. Formerly called tic douloureux, trigeminal neuralgia is a chronic, recurring disorder consisting of dozens of 20–30-second jabs daily of agonizing, sharp pain extending along one of the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal neuralgia most commonly affects the V2 division of the trigeminal nerve (see Fig. 4-12). Unlike the other headaches, touching the affected area can provoke the pain. Stimulating these sensitive areas or trigger zones – by eating, brushing one’s teeth, or drinking cold water as well as by touching – evokes a dreadful shock. Thus, patients in the midst of an attack hesitate to eat, brush their teeth, or speak. They tend to become reclusive. Fortunately, in a characteristic reprise, trigeminal neuralgia abates at night, allowing the patient a full night’s sleep. Trigeminal neuralgia develops in women more often than men and typically only after age 60 years, making it one of the most important causes of headache in the elderly (see Box 9-4).

Abramowicz M. Drugs for migraine. editor. Med Lett. 2011;9:7–12.

Allais G, Gabellari IC, Airola G, et al. Headache induced by the use of combined oral contraceptives. Neurol Sci. 2009;30(Suppl 1):S15–S17.

Bigal ME, Lipton RB. The differential diagnosis of chronic daily headaches: An algorithm-based approach. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:263–272.

Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive acute migraine medication use and migraine progression. Neurology. 2008;71:1821–1828.

Bigal ME, Liberman JN, Lipton RB. Obesity and migraine: a population study. Neurology. 2006;66:545–550.

Breslau N, Lipton R, Stewart W, et al. Comorbidity of migraine and depression: investigating potential etiology and prognosis. Neurology. 2003;60:1308–1312.

Chronicle E, Mulleners W. Anticonvulsant drugs for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2004. CD003226

Dodick DW. Chronic daily headache. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:158–165.

Eccleston C, Yorke L, Morley S, et al. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2003. CD003968

Evers S, Marziniak M. Clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment of medication-overuse headache. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:391–401.

Francis GJ, Becker WJ, Pringsheim T. Acute and preventative pharmacologic treatment of cluster headache. Neurology. 2010;75:463–473.

Frese A, Eikermann A, Frese K, et al. Headache associated with sexual activity. Neurology. 2003;61:796–800.

Gronseth G, Cruccu G, Alksne J, et al. Practice parameter: The diagnostic evaluation and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurologic Societies. Neurology. 2008;71:1183–1190.

Hamelsky SW, Lipton RB. Psychiatric comorbidity of migraine. Headache. 2006;46:1327–1333.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders (2nd edition). Cephalalgia. 2004;24:1–160.

Hershey AD, Lipton RB. Lifestyles of the young and migrainous. Neurology. 2010;75:680–681.

Kirchmann M, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. Basilar-type migraine: clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic factors. Neurology. 2006;66:880–886.

Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: Pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents. Report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215–2224.

Linde K, Rossnagel K. Propranolol for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2004. CD003225

Lipton RB, Varon SF, Grosberg B, et al. Onabotulinumtoxin A improves quality of life and reduces impact of chronic migraine. Neurology. 2011;77:1465–1472.

Loder E. Triptan therapy in migraine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:63–70.

Lyngberg AC, Rasmussen BK, Jørgensen T, et al. Prognosis of migraine and tension-type headache: A population-based follow-up study. Neurology. 2005;65:580–585.

Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Dodick D. Acute treatment and prevention of menstrually related migraine headache. Neurology. 2008;70:1555–1563.

Saper JR, Lake AE, Hamel RL, et al. Daily scheduled opioids for intractable head pain. Long-term observations of treatment program. Neurology. 2004;62:1687–1694.

Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Lu SR. Chronic daily headache in adolescents. Neurology. 2009;73:416–422.

Winawer MR, Hesdorffer DC. Migraine, epilepsy, and psychiatric comorbidity. Neurology. 2010;74:1166–1168.

Chapter 9 Questions And Answers

Given the differential diagnosis of an acutely occurring, severe headache, neurologists, before or after obtaining computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), perform a lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (see Table 20-1). High-dose, intravenous antibiotics remain the standard treatment in cases of established or suspected bacterial meningitis. Vaccinations will greatly reduce the incidence of meningococcal meningitis.

2. Following 5 days of moderate bitemporal headaches, a woman brought her 45-year-old husband for psychiatric evaluation because he began to develop episodes of purposeless, repetitive behavior. On examination, he was febrile, disoriented, inattentive, and unable to recall any recent or past events. CT revealed no abnormalities in the brain or sinuses. His CSF contained 89 white blood cells/mm3, of which 90% were lymphocytes; 45 mg/dL glucose; and 80 mg/dL protein. An electroencephalogram showed spikes overlying both temporal lobes. Which is the most likely diagnosis?

d. His complex partial seizures and amnesia reflect temporal lobe dysfunction. In view of the delirium, fever, and the CSF profile, the underlying illness is most likely an infectious process. Herpes simplex encephalitis, the most common nonepidemic encephalitis, has a predilection for the temporal lobes, which house major portions of the limbic system, and the undersurface of the frontal lobes. Herpes simplex encephalitis typically produces this picture of fever, delirium, complex partial seizures, and amnesia. Severe cases cause temporal lobe hemorrhagic infarctions, which allow some blood to seep into the CSF. Because of the bilateral temporal lobe damage, herpes simplex encephalitis survivors may exhibit the human form of the Klüver–Bucy syndrome (see Chapter 16).

6. A 4-year-old boy has had several headaches with incapacitating nausea and vomiting complicated by confusion, incoherence, and agitation, but no paresis or nuchal rigidity. Serum lactate and pyruvate levels rise to very high levels during these attacks. Between attacks, he is clinically normal. Which of the following is the most likely explanation for the child’s episodes?

14-d; 15-c; 16-b; 17-l; 18-j; 19-h; 20-a; 21-g, i, or l; 22-i; 23-l; 24-m; 25-f.

34–37. Does sleep ameliorate the following headache types? (Yes/No)

39. An adolescent schoolgirl drew this sketch of what she saw immediately before her headaches (see figure), which are accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The headaches prevent her from attending school or cause her teacher to send her to the nurse’s office. Of the following, which is the most plausible interpretation of her visions?

d. Some migraine sufferers, especially children, perceive distortions of themselves, other people, or their environment as a prelude (aura) to the headache phase of an attack. One example, as in this figure, consists of a parent shrinking (micropsia) or growing (macropsia). Some patients have likened the symptom to looking in a “fun-house mirror without the fun.” Neurologists have termed the micropsia/macropsia phenomenon the “Alice in Wonderland” syndrome because of its similarity to Alice’s experience after she drinks the potion in the famous novel (see Box 12-1).

57. A 40-year-old woman has had migraine since adolescence and depression for the previous 10 years. Her psychiatrist changed her antidepressant to an SSRI, which initially seemed to reduce her headaches and improve her mood. However, after 1 month her headaches returned with much greater severity. Her family brought her to the emergency room when she developed agitated confusion and tremulousness. Her blood pressure is 110/70 mmHg and her temperature 100°F. Her urine contains a small quantity of myoglobin. Which of the following is the most likely cause of her condition?

61–68. Match the headache (61–68) with one or more of its causes or precipitants (a–k):

71. A 23-year-old woman told her physician that, beginning about 10 minutes before most of her headaches, which are usually one-sided and throbbing, she develops jagged lines surrounding a blurred region in the corner of her left eye. The visual distortion expands to fill most of that eye and then flickers. Over several minutes, it expands beyond both eyes. She said, “It engulfs everything. I am mesmerized.” Then suddenly it shrinks to a small area in the lower outside corner of her left eye and disappears. She sketched this picture showing the visual distortion from her perspective (see figure). Which is the most likely variety of her headaches?

72. A 26-year-old waitress reports 6 weeks of a progressively severe, dull headache. Aside from her optic disks (see figure) and enlarged blind spots on formal visual field determination, her neurologic examination discloses no abnormalities. Her CT and MRI show small ventricles, but no mass lesions, hydrocephalus, or other abnormality. Which is the most likely diagnosis?

73. In the case described in Question 72, a lumbar puncture showed that the opening pressure was 350 mm H2O, but the CSF was acellular and had normal glucose and protein. The patient had menstrual irregularity and her body mass index was calculated to be 48 kg/m2. Which is the best initial treatment?

74. A 28-year-old surgical intern, fighting off the effects of sleep deprivation, drinks at least three cups of coffee each day. Her strategy allows her to work, sleep, and socialize. Various professional and social stressors eventually drive her to psychiatric counseling. A psychiatrist begins psychotherapy and prescribes fluvoxamine. Rather than improving, the intern develops anxiety, palpitations, insomnia, and sometimes a fine tremor. Which is the most likely explanation of her new symptoms?