Headache

When assessing a patient with headache, it is important to exclude life-threatening causes first.

History

Onset

Sudden onset of severe pain is usually due to a vascular cause, especially subarachnoid haemorrhage from a ruptured berry aneurysm. Cluster headache and migraine intensify over minutes and may last several hours, while meningitis tends to evolve over hours to days. Progressive severe headaches that develop over days or weeks should lead to the consideration of raised intracranial pressure from tumour or chronic subdural haemorrhage. The onset of headache may be preceded by an aura with migraine.

Site

Classically, headache from migraine is unilateral. Temporal arteritis leads to more localised pain over the superficial temporal arteries that can be accompanied by jaw claudication. Ocular pain is experienced with glaucoma, and retro-orbital pain with cluster headaches.

Character

The intensity of pain contributes little when discriminating between the causes; however, the character of the pain may be useful. Patients with tension headache often complain of a tight band-like sensation; this is in contrast to the pain experienced with raised intracranial pressure, which is often reported to have a bursting quality. Migraine-related and temporal arteritis headaches have a throbbing character.

Precipitating factors

Headache originating from raised intracranial pressure is precipitated by changes in posture, coughing or sneezing, and is often worse in the mornings. Photophobia may be experienced by patients suffering with migraine, meningitis or glaucoma. They may prefer to lie in a darkened room when headaches arise. Certain foods such as cheese, red wine and chocolate are known to precipitate migraine. It is very common for headache to be precipitated by systemic illnesses such as a cold or influenza. Headache precipitated by touch occurs with superficial temporal artery inflammation from temporal arteritis. A drug history may elucidate the relationship between the administration of drugs with headache as a side-effect, such as glyceryl trinitrate and nifedipine. Alternatively, headache can also result from substance withdrawal in substance-dependent patients.

Associated symptoms

Neck stiffness (meningism) is experienced with both meningitis and subarachnoid haemorrhages. Visual disturbances in the form of haloes occur with glaucoma. Flashing lights and alternations in perception of size may be reported by patients suffering with migraine, and this may be accompanied by photophobia, nausea and vomiting. Transient neurological deficits may also occur. However, progressive neurology associated with headache is more suggestive of an intracranial space-occupying lesion, such as haemorrhage, abscess and tumour. Unilateral visual loss may result as a complication of temporal arteritis, and this may be accompanied by proximal muscle pain, stiffness and weakness or tenderness. Conjunctival infection is experienced with both glaucoma and cluster headaches, along with lacrimation, which is a feature of the latter. With normal pressure hydrocephalus in adults, headaches are associated with dementia, drowsiness, vomiting and ataxia.

Examination

Temperature

Pyrexia may indicate the presence of systemic infection, meningitis or vasculitis.

Inspection

An assessment of the conscious state should be undertaken and quantified on the GCS. Impairment of consciousness is a sign of a serious underlying aetiology, such as meningitis, subarachnoid haemorrhage and raised intracranial pressure. Inspection of the eyes may reveal conjunctival infection with glaucoma and cluster headaches during an acute attack. With acute angle-closure glaucoma, the cornea is hazy and the pupil fixed and semi-dilated. Petechial haemorrhages classically occur with meningococcal meningitis.

Palpation

Tenderness along the course of the superficial temporal artery, with absent pulsation, is consistent with temporal arteritis.

Neurological examination

A detailed neurological examination is performed to identify the site of any structural lesion. Unilateral total visual loss can be precipitated by temporal arteritis due to ischaemic optic neuritis. Visual field defects (hemianopia) can be caused by contralateral lesions in the cerebral cortex. Fundoscopy is performed to identify papilloedema from raised intracranial pressure.

Transient hemiplegia can occur with migraine, but progressive hemiplegia is more indicative of a space-occupying lesion, such as a tumour or intracranial haemorrhage. Neck stiffness is a feature of both meningitis and subarachnoid haemorrhage. With meningitis, Kernig’s sign (pain on extending the knee with the hip in a flexed position) may be present.

General Investigations

■ FBC

WCC ↑ meningitis, cerebral abscess and systemic infection.

■ ESR and CRP

↑ temporal arteritis, infection, intracranial bleeding.

■ U&Es

Hypertensive headaches with renal disease.

■ Alkaline phosphatase

Elevated in Paget’s disease.

■ Radiology

Cervical spine X-rays identify cervical spondylosis and cranial X-rays may reveal Paget’s disease.

Specific Investigations

In most cases, the diagnosis can be made on clinical assessment. Features in the history and examination may guide specific investigations.

■ Blood cultures

With meningitis, systemic infection.

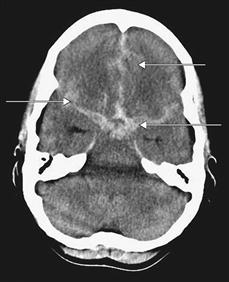

■ CT/MRI

Visualisation of the anatomical structures in the cranium is very useful in the presence of neurological deficit. Cerebral tumours may be visualised as high or low-density masses. Intracranial bleeding can be identified as areas of high density during the first two weeks. An extradural haematoma presents as a lens-shaped opacity, and subdural haematoma presents as a crescent-shaped opacity. After two weeks, intracranial haematomas become isodense and more difficult to visualise. Following subarachnoid haemorrhage, blood may be visualised in the subarachnoid space. Occasionally the offending aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation may be imaged. Enlargement of the ventricles may be an indication of hydrocephalus. Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI will increase the sensitivity to diagnose cerebral abscesses.

■ Lumbar puncture

A lumbar puncture may be undertaken following the exclusion of raised intracranial pressure, when there is suspicion of meningitis or subarachnoid haemorrhage. The opening pressure is recorded and the CSF obtained is inspected for consistency and colour. The consistency of the CSF is turbid with meningitis, and yellow staining of the CSF (known as xanthochromia) occurs with subarachnoid haemorrhage, owing to breakdown of haemoglobin from red blood cells. The CSF is then sent for microscopy, culture, cytology and biochemical analysis for glucose and protein. An abnormal increase in white cells may be seen on microscopy with meningitis. With bacterial or tuberculous meningitis, the glucose is low and protein content high. With viral meningitis the glucose content is normal and protein content mildly elevated. A lumbar puncture may also be helpful in cases of benign intracranial hypertension.

■ Temporal artery biopsy

Inflammation and giant cells may be seen with temporal arteritis. A normal biopsy does not, however, exclude the disease, as there may be segmental involvement of the temporal artery.

■ Intraocular pressure measurements

Tonometry will reveal high intraocular pressures with glaucoma.