Headache

Perspective

Up to 85% of the U.S. adult population reports significant headaches at least occasionally, and 15% does so on a regular basis. Headache as a primary complaint represents 3 to 5% of all emergency department (ED) visits. The vast majority of patients who have a primary complaint of headache do not have a serious medical cause for the problem. Tension headache accounts for approximately 50% of patients visiting the ED, another 30% have headache of unidentified origin, 10% have migraine-type pain, and 8% have headache from other potentially serious causes (e.g., tumor, glaucoma). It is estimated that less than 1% of patients who come to the ED with headache have a life-threatening organic disease.1 These percentages can create a false sense of security, and headache is disproportionately represented in emergency medicine malpractice claims. Although still rare, the most commonly encountered life-threatening cause of severe sudden head pain is subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); approximately 20,000 potentially salvageable cases of SAH are seen in EDs each year. It is estimated that 25 to 50% of these are missed on the first presentation to a physician.2 The other significant, potentially life-threatening causes of headache occur even less frequently. Meningitis, carbon monoxide poisoning, temporal arteritis, acute angle-closure glaucoma, intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and increased intracranial pressure can often be linked with specific historical elements and physical findings that facilitate their diagnosis.

Diagnostic Approach

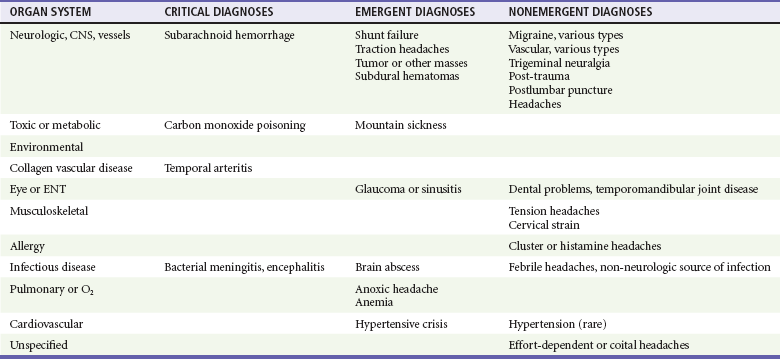

The differential diagnosis of headache is complex because of the large number of potential disease entities and the diffuse nature of many types of pain in the head and neck region (Table 20-1). However, in evaluating the patient with a headache complaint, the top priority is to exclude the life-threatening causes: SAH and ICH, meningitis, encephalitis, and mass lesions. Carbon monoxide is an exogenous toxin, the effects of which may be reversible by removing the patient from the source and administering oxygen. Carbon monoxide poisoning is a rare example of a headache in which relatively simple interventions may quickly improve a critical situation. On the contrary, returning the patient to the poisoned environment without a diagnosis could be lethal.

Pivotal Findings

The history is the pivotal part of the workup for the patient with headache (Table 20-2).

Table 20-2

| SYMPTOM | FINDING | POSSIBLE DIAGNOSES |

| Sudden onset of pain | Lightning strike or thunder clap with any decreased mentation, any positive focal finding, or intractable pain | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| “Worst headache of my life” | Associated with sudden onset | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| Near syncope or syncope | Associated with sudden onset | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| Increase with jaw movement | Clicking or snapping; pain with jaw movement | Temporomandibular joint disease |

| Facial pain | Fulminant pain of the forehead and area of maxillary sinus; nasal congestion | Sinus pressure or dental infection |

| Forehead or temporal area pain (or both) | Tender temporal arteries | Temporal arteritis |

| Periorbital or retro-orbital pain | Sudden onset with tearing | Temporal arteritis or acute angle-closure glaucoma |

1. The patient should be asked to describe the pattern and onset of the pain. Patients often relate having had frequent and recurrent headaches similar to the one they have on the current ED visit. A marked variation in headache pattern can signal a new or serious problem. The rate of onset of pain may have significance. Pain with rapid onset of a few seconds to minutes is more likely to be vascular in origin than pain that developed over several hours or days. However, a slow onset should not be solely relied on to rule out potential life-threatening causes for headache.

Careful questioning about the onset of headache may lead to the correct diagnosis of SAH, even if the pain is improving at the time of evaluation.3

2. The patient’s activity at the onset of the pain may be helpful. Headaches that come on during severe exertion have a relationship to vascular bleeding, but there is enough variation to make assignment to any specific cause highly variable. The syndrome of postcoital headache is well known, but coitus is also a common time of onset for SAH. These headaches require the same evaluation on initial presentation as any other exertion-related head pain.

3. If there is a history of head trauma, the differential diagnosis and emergent causes are narrowed significantly. The considerations now focus on epidural and subdural hematoma, traumatic SAH, skull fracture, and closed-head injury (i.e., concussion and diffuse axonal injury).

4. The intensity of head pain is difficult to quantify objectively. Almost all patients who come to the ED consider their headaches to be severe. Use of a pain scale may help differentiate patients initially but has more value in monitoring their response to therapy. Rapid resolution of pain in the ED, either from time or therapy, also should not be relied on to rule out serious causes of headache.

5. The character of the pain (e.g., throbbing, steady), although sometimes helpful, may not be adequate to differentiate one type of headache from another.

6. The location of head pain is helpful when the patient can identify a specific area. It is useful to have the patient point or try to indicate the area of pain; the emergency physician can then properly examine that area. Unilateral pain is more suggestive of migraine or a localized inflammatory process in the skull (e.g., sinus) or soft tissue.4 Occipital headaches are classically associated with hypertension. Temporal arteritis, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disease, dental infections, and sinus infections frequently have a highly localized area of discomfort. Meningitis, encephalitis, SAH, and even severe migraine, although intense in nature, are usually more diffuse in their localization.

7. Exacerbating or alleviating factors may be important. Patients whose headaches rapidly improve when they are removed from their environment or recur each time they are exposed to a particular environment (e.g., basement workshop) may have carbon monoxide poisoning. Most other severe causes of head pain are not rapidly relieved or improved when patients get to the ED. Headaches on awakening are typically described with brain tumors. Intracranial infections, dental infections, and other regional causes of head pain tend not to be improved or alleviated before therapy is given.

8. Associated symptoms and risk factors may relate to the severity of headache but rarely point to the specific causes (Box 20-1). Nausea and vomiting are completely nonspecific. Migraine headaches, increased intracranial pressure, temporal arteritis, and glaucoma can all manifest with severe nausea and vomiting, as can some systemic viral infections with headache. Such factors may point toward the intensity of the discomfort but are not specific in establishing the diagnosis. Immunocompromised patients are at risk for unusual infectious causes of headache. Toxoplasmosis, cryptococcal meningitis, and abscess are very rare but may be seen in patients with a history of HIV or another immunocompromised state. This subset of patients may have serious central nervous system infection without typical signs or symptoms of systemic illness (e.g., fever and meningismus).

9. A prior history of headache, although helpful, does not rule out current serious problems. It is extremely helpful, however, to know that the patient has had a workup for severe disease. Previous ED and outpatient visits and computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, and other forms of testing can provide support for or help rule out a specific diagnosis. Patients with migraine, cluster, and tension headaches tend to have a stereotypical recurrent pattern. Adherence to these patterns is also helpful in deciding the degree to which a patient’s symptoms are pursued.

Physical Examination

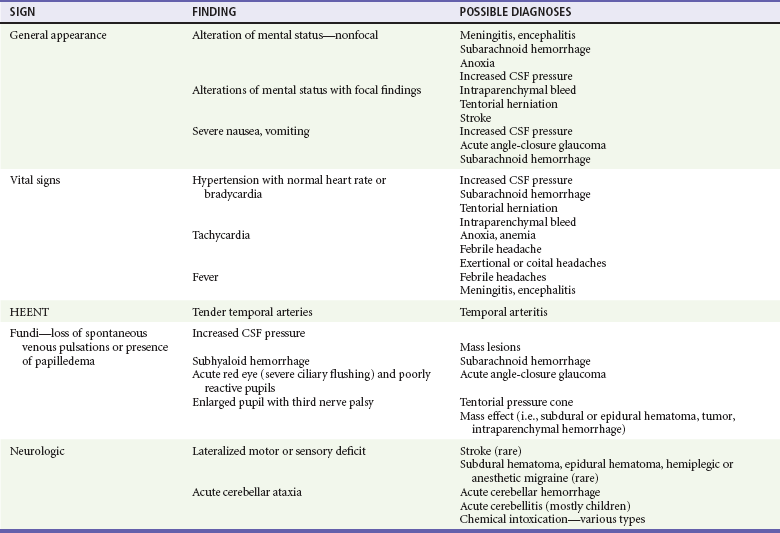

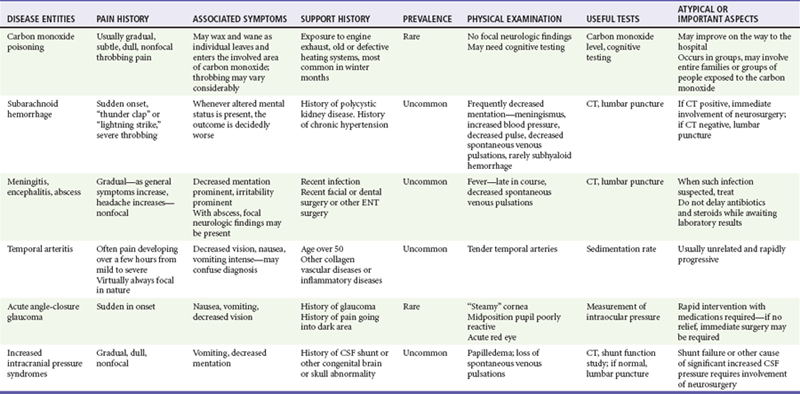

Physical findings associated with various forms of headache are listed in Table 20-3.

Ancillary Testing

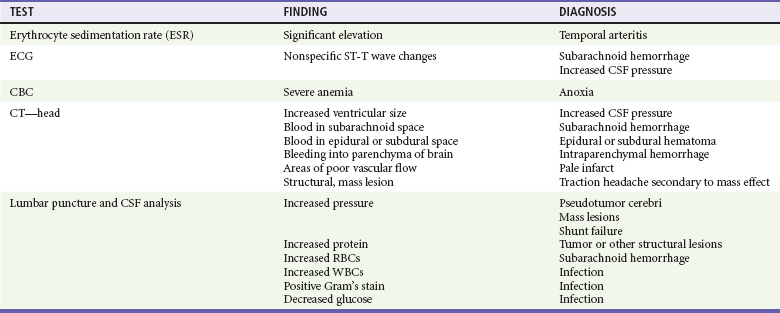

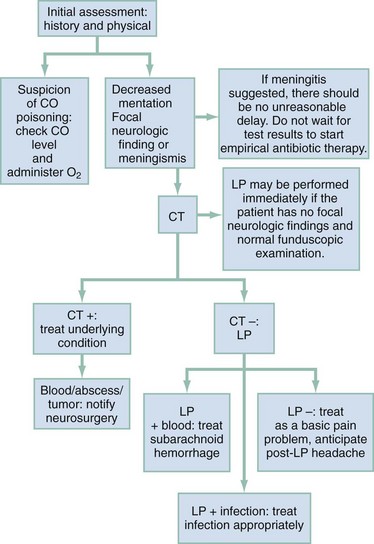

The vast majority of headache patients do not require additional testing (Table 20-4). The most common and consequential mistake made by emergency physicians in the workup of the headache patient is believing that a single CT scan clears the patient of the possibility of SAH or other serious intracranial disease. Brain CT can miss 6 to 8% of patients with SAH, especially patients with minor (grade I) SAH, who are most treatable.5,6 The sensitivity of CT for identifying SAH is reduced by nearly 10% for symptom onset greater than 12 hours and by almost 20% at 3 to 5 days. The basic approach to integrating CT and lumbar puncture in the assessment of headache is outlined in Figure 20-1.7–10

Differential Considerations

Sequential evaluation of the patient’s condition and response to therapy and assessment of ancillary data will confirm a working diagnosis or trigger a reconsideration of alternatives, including more serious conditions (Table 20-5).7

Management

Headache, although a frequent chief complaint, is a nonspecific symptom, and the speed and intensity of the initial evaluation and treatment are guided by the initial presentation (described earlier) and, particularly, the patient’s mental status. Pain should be mitigated as soon as possible. The pain medication of choice depends on the working diagnosis of the patient’s headache. If migraine is suspected, parenteral therapy is directed accordingly (see Chapter 103). For nonspecific mild to moderate headache, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication is appropriate, in analgesic doses. Opioids generally are not first-line management for any type of headache pain, except when ICH (including SAH) is thought to be present, conditions for which opioid analgesia is effective and beneficial.

References

1. Barton, CW. Evaluation and treatment of headache patients in the emergency department: A survey. Headache. 1994;34:91.

2. Mayer, PL, et al. Misdiagnosis of symptomatic cerebral aneurysm: Prevalence and correlation with outcome at four institutions. Stroke. 1996;27:1558.

3. Day, JW, Raskin, NH. Thunderclap headache: Symptom of unruptured cerebral aneurysm. Lancet. 1986;2:1247.

4. Olesen, J, Lipton, RB. Migraine classification and diagnosis: International Headache Society criteria. Neurology. 1994;44(Suppl 4):S6.

5. Edlow, J, Caplan, L. Avoiding pitfalls in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:29.

6. McCormack, RF, Hutson, A. Can computed tomography angiography of the brain replace lumbar puncture in the evaluation of acute-onset headache after a negative noncontrast cranial computed tomography scan? Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:444–451.

7. Edmeads, J. Emergency management of headache. Headache. 1988;28:675.

8. Silberstein, SD. Evaluation and emergency treatment of headache. Headache. 1992;32:396.

9. Byyny, RL, et al. Sensitivity of noncontrast cranial computed tomography for the emergency department diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:697–703.

10. Perry, JJ, et al. Is the combination of negative computed tomography result and negative lumbar puncture result sufficient to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:707–713.