6 Headache

Introduction

Headache is the most common neurological condition for which consultation is sought.1 The approach adopted in this review offers a clinical strategy to guide the family doctor without need to resort to the International Headache Society (IHS) classification.2

This should not be interpreted as undervaluing that classification,2 which is pivotal in allowing international consensus necessary for clinical research and trials, but clinical trials do not necessarily reflect everyday practice. The IHS criteria2 allow researchers around the world to recruit patients with rare headache diagnoses to trial novel treatments with the ability to recruit sufficient patients to achieve statistical power. While this is fundamental for scientific progress, it does little to assist the general practitioner who sees very few cases of such conditions; for example, cluster headache. Cluster headache was not randomly chosen for this example, but rather because it is diagnosed more often by family doctors than neurologists, and affects less than 1% of those with headaches.3

Broad-Brushed Clinical Approach

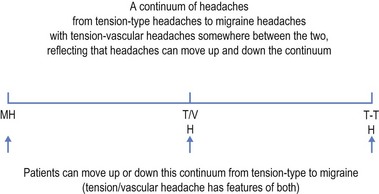

A practical, if unscientific, approach to headache is to consider that primary headaches lie on a continuum (see Fig 6.1). At one end of this continuum lies tension-type headaches, while at the other is migraine (with or without aura). In the middle is what might be called tension-vascular headache with features of both, a term excluded from the IHS classification.2

Differentiating tension-type headache from migraine

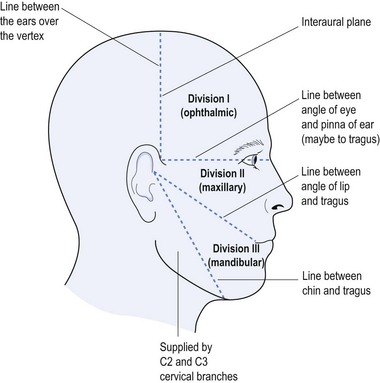

This starts with a concise history dating from the onset of the headaches. The doctor needs to know: how long the patient has had headaches; where they occur in the head (unilateral, bilateral, frontal, occipital, vertex or completely generalised); the nature of the pain (be it constant and gripping, throbbing and pulsating, or stabbing and lancinating); associated features (visual symptoms, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms of nausea and/or vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia or osmophobia); the frequency and duration; and precipitating and relieving factors. This will assist in differentiating migraine from tension-type headache (see Table 6.1).

TABLE 6.1 Differentiation between migraine and tension-type headaches

| Migraine | Tension headache |

|---|---|

| Unilateral—often in the temple | Bilateral—like a band or in both temples |

| Throbbing pain—pulsating | Tight, gripping pain—constant |

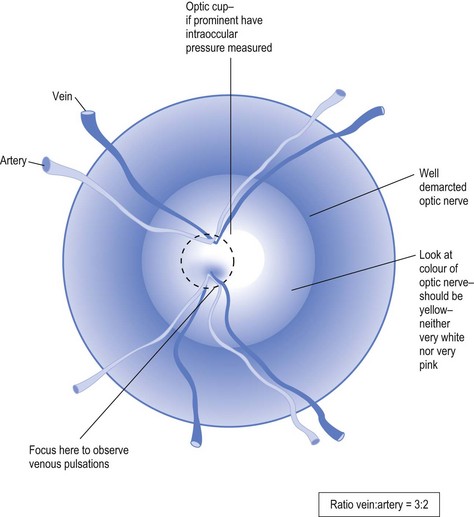

Detailed physical examination is warranted for all headache patients, particularly fundoscopy and searching for focal neurological signs, which should alert the doctor to more serious illness and the need for investigation. It is most important to look for venous pulsations on fundoscopy, which, if present, exclude raised intra-cranial pressure (see Fig 6.2).

Red Flags for the Need for Further Investigation

Some symptoms should alert the doctor to the need for further testing (see Box 6.1).

Box 6.1 Need for further investigation

These ‘red flags’ include marked exacerbation of headaches with coughing, straining or sneezing.4 If the headaches are provoked by stooping or postural changes, the doctor should order cerebral imaging. Associated neurological symptoms, such as sensory changes or weakness, demand further testing. Headache associated with eye movement and impaired vision suggests retrobulbar neuritis. Headache with enlarged blind spot may suggest papilloedema or raised intracranial pressure. Headache with stiff neck, nausea and vomiting should be sent to the hospital for consideration for lumbar puncture.

Diagnostic Criteria

a Tension-type headache

This is the most common type of headache in which attacks are usually mild to moderate but can be quite intrusive and severe.5 They are classified within the IHS classification2 as episodic or chronic, for which the underlying cause is often presumed to be emotional but is uncertain with a variety of aetiologies considered.5 It is said to be most common in the fifth decade with females affected somewhat more than males.5

Infrequent headaches do not usually cause medical presentation unless the pain is significant. Those who present may complain of frontal, occipital or band-like pain that usually has tight and gripping quality (see Table 6.1). It may involve the neck, causing concern of neck pathology that may or may not be found. The finding of neck pathology, such as osteoarthritis, does not necessarily have any relevance to the headache as both conditions are very common and may co-exist.

A similar picture can emerge from excessive use of analgesics, and medication-overuse headache can be overlooked unless the doctor has a high index of suspicion.

b Migraine

While migraine is often perceived as the most common headache type, the relative prevalence is approximately 5% for migraine as compared to approximately 27% for tension-type headache in an adult population.6 This is important because the correct diagnosis dictates the appropriate treatment.

Migraine is classified into those with and without aura,7 which replaces the older terms of ‘common’ and ‘classical’ migraine. Unlike tension-type headaches, migraines are usually unilateral, throbbing in quality and often associated with nausea, maybe vomiting, and visual symptoms such as teichopsia (zigzag shimmering lights), fortification spectra (like the pointed top of a cowboy fortress), photons of light or a rainbow effect (Table 6.1). Patients may describe coloured lights (as if looking through a prism). The patient may experience photophobia, phonophobia and/or osmophobia.7

The relationship between headaches and alcohol is helpful as alcohol relaxes muscles and hence can relieve tension-type headaches, while it exacerbates migraines (see Table 6.1). Other provocateurs for migraines include: low blood sugar; hormonal changes (such as catamenial); odours (such as perfumes); allergies; excess or insufficient sleep; and transformation from other headache types.

c Symptomatic headaches

The community cannot afford to investigate every headache when tension-type headaches are so common. Conversely, one cannot ignore headaches that are symptomatic of underlying illness. Some of the ‘red flags’ have already been discussed (Box 6.1). Headaches exacerbated by coughing, sneezing or stooping justify urgent cerebral imaging. Absence of venous pulsations on fundoscopy or evidence of raised intracranial pressure with stiff neck call for more detailed assessment and referral. It must be remembered that 10% of the normal population do not have venous pulsations.

Sudden onset of severe headaches with nausea, vomiting, stiff neck and visual obscuration may suggest subarachnoid haemorrhage. Skin rash, symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection, generalised aches and pains, photophobia and possible exposure to infected individuals may suggest meningoencephalitis. Lumbar puncture is warranted in these patients, usually preceded by cerebral imaging and definitely by fundoscopy, to exclude raised intracranial pressure (see Fig 6.2).

It must be remembered that weakness and sensory changes follow set patterns within neurological evaluation (see Chs 4 and 5). Similarly, headaches associated with such symptoms and signs that do not conform to anatomically defined patterns, suggest psychological illness and may justify an alternative approach to management.

d Other headache types

While there are many headache types included within the IHS classification2 only the most common forms, referable to general practice, will be discussed in this section.

Management

Tension-type headaches respond to oral aspirin 500–1000 mg or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents.5 Many of these are available without prescription, thereby allowing excessive use, which may itself cause headaches. Analgesia-overuse headaches always must be considered and addressed when necessary.

Headache treatment is not restricted to pharmacological intervention and should include: review of lifestyle issues; counselling; exploration of diet and alcohol consumption; work-related habits; and an holistic approach to patient care, that transcends headache boundaries and is relevant to all headache types.

Immediate migraine intervention includes the triptans or ergot-containing compounds taken at the very onset of symptoms (either the aura or headache). The triptans include sumatriptan, zolmitriptan and naratriptan, which may cause a sensation of chest pressure, flushing, paraesthesia and drowsiness.6 Some patients may respond to one type of triptan and not another. Many ergot-containing compounds are no longer commercially available and may require a compounding pharmacist, but should not be lightly discarded from the therapeutic options.

Pizotifen offers an effective prophylaxis against migraines but little benefit in tension-type headaches. Thus it is mandatory to differentiate between them (see Table 6.1). The dosage starts at 0.5 mg b.d. and can be increased up to 1.5 mg t.d.s. (IX per day). Side-effects may include increased appetite and fatigue.

For those headaches that fall somewhere between tension-type headaches and migraines, so-called tension-vascular headaches (see Fig 6.1), propranolol offers prophylaxis. Immediate headache cessation may rely on either of the above approaches though more commonly the tension-type headache approach is favoured.

Recently use of antiepileptic medications, such as valproate, topiramate, gabapentin,12 pregabalin and even levetiracetam,13 have been used for headache therapy but it is wise to involve a consultant before embarking on their use. Similar caution should apply to the use of botulinum toxin that also has received recent acclaim following clinical trial.14

While cluster headache is rare, its features are classical, thereby making diagnosis easier. Immediate headache treatment may be offered by oxygen inhalation by a non-rebreathing mask at 6.10 L/min for 15 minutes. Subacute triptan administration (for example, 6 mg sumatriptan) or intranasal triptan (such as sumatriptan or 10 mg zolmitriptan) is efficacious. Prophylaxis is given early in an attack and maintained for a couple of weeks after it. Virapamil, a calcium channel blocker given 80–160 mg t.d.s. or 240 mg sustained release daily, is currently accepted treatment. Lithium is also used, as are steroids.8

1 O’Flynn N, Risdale L. Headache in primary care: how important is diagnosis to management? Brit J GP. 2002;52:569-573.

2 Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl. 1):9-160.

3 May A. Cluster headache: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management, Review: cluster headaches. Lancet. 2005;366:843-855.

4 Dodick DW. Clinical clues and clinical rules: primary vs secondary headache. Adv Stud Med. 2003;3:S550-S555.

5 Loder E, Rizzoli P. Clinical review: tension-type headaches. BMJ. 2008;336:88-92.

6 Fong KJ. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of primary headache disorders. Medical Session, June. Online. Available http://www.fmshk.com.hk/article/821.pdf, 2002. 26 April 2011

7 Kelman L. The place of osmophobia and taste abnormalities in migrane classification: a tertiary care study of 1237 patients. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:940-946.

8 Beck E, Sieber W, Trejo R. Management of cluster headache. American Family Physician. 2005;71(4):717-724.

9 Biondi DM. Cervicogenic headache: a review of diagnostic and treatment strategies. J American Osteopathic Association. 2005;105(suppl. 4):16-22.

10 Schwedt T, Matharu M, Dodick D. Thunderclap headache. Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(7):621-631.

11 Bigal ME, Lipton RB. The differential diagnosis of chronic daily headaches: an algorithm-based approach. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:263-272.

12 Spira PJ, Beran RG. Gabapentin in the prophylaxis of chronic daily headache: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Neurology. 2003;61(12):1753-1759.

13 Beran RG, Spira PJ. Levetiracetam in chronic daily headache: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study: The Australian Keppra Headache Trial [AUS-KHT]. Cephalalgia. 2010;Nov:1-7.

14 Silberstein SD, Göbel H, Jensen R, et al. Botulinum toxin type A in the prophylactic treatment of chronic tension-type headache: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(7):790-800.