Headache

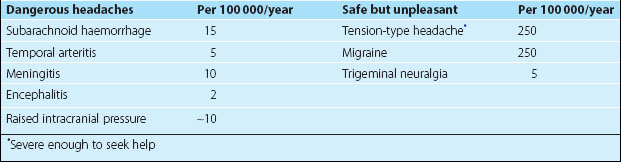

Headache is common. Almost everyone has a headache at some time in life. Headache accounts for 2% of general practice visits and 20% of neurological outpatients. Headaches are only very rarely sinister. However, it is important to recognize certain dangerous headaches, and the major types of safe but unpleasant headaches (Table 1).

History

Associated symptoms – does anything else occur with the headache, e.g. flashing lights, numbness, sickness or a runny nose? Are there any other neurological symptoms suggesting focal neurological disease?

Associated symptoms – does anything else occur with the headache, e.g. flashing lights, numbness, sickness or a runny nose? Are there any other neurological symptoms suggesting focal neurological disease? Triggers – does anything seem to bring the headache on, particularly bending, coughing or straining?

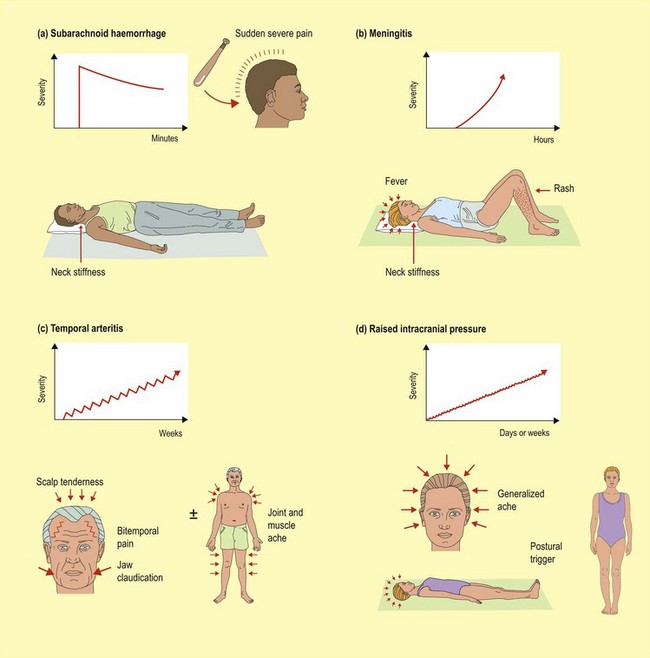

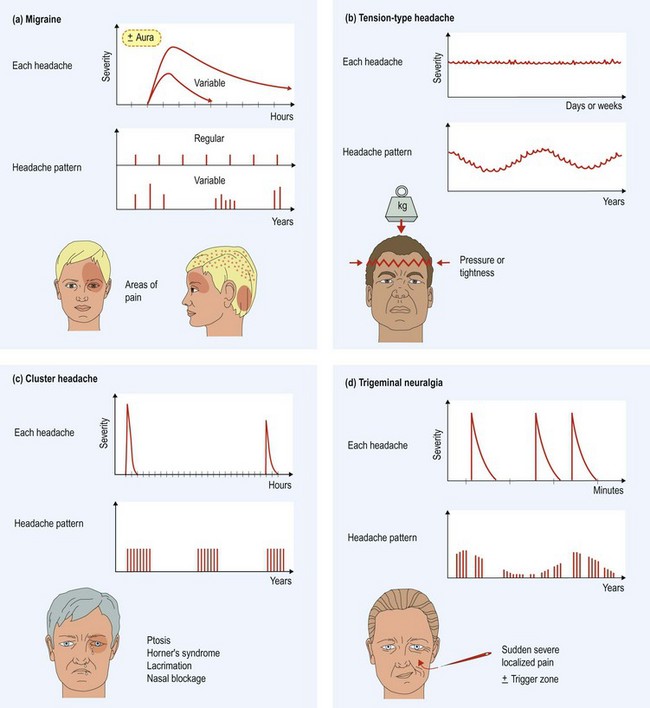

Triggers – does anything seem to bring the headache on, particularly bending, coughing or straining?The different features of the common but unpleasant and the rare but dangerous headaches are summarized in Figures 1 and 2.

Dangerous headaches

These headaches are single episodes of headache that develop in seconds to weeks. All are uncommon.

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

These patients classically present with a sudden severe headache: ‘like being hit by a baseball bat’ (Fig. 1a). There may be associated loss of consciousness and focal neurological signs. The subarachnoid blood provokes neck stiffness. Currently up to 50% of patients who present with subarachnoid haemorrhage are misdiagnosed by the first doctor who sees them. A high threshold of suspicion is needed (p. 72).

Meningitis

Meningitis is characterized by progressive headache developing over hours or days (Fig. 1b). There is an associated fever and neck stiffness, and there may be a rash and impaired consciousness. As early treatment favours a good prognosis, a high threshold of suspicion is needed (p. 98).

Temporal arteritis (or giant cell arteritis)

The headache is insidious in onset and may be unilateral or more generalized, though it usually produces bitemporal pain (Fig. 1c). The scalp is often tender. A specific symptom is ‘jaw claudication’, the development of pain in the muscles of mastication on chewing. Twenty-five per cent of patients also have generalized joint and muscle aching typical of polymyalgia rheumatica.

Raised intracranial pressure

The ‘classical’ headaches of raised intracranial pressure (ICP; p. 48) are generalized and made worse or brought on by manoeuvres that increase ICP such as coughing, bending or lying down (Fig. 1d); for this reason they are worse on waking in the morning and tend to clear within a short time of getting up. They may be associated with vomiting. There may be false localizing signs such as 6th or 3rd nerve palsies and signs of raised ICP such as papilloedema. There may be associated focal signs and altered consciousness depending on the cause of the raised ICP. In only 20% of patients with intracranial tumours is headache the presenting feature.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension and intracranial venous thrombosis

Diagnosis of IIH depends on demonstrating no structural cause for the raised ICP, with magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance venography and measuring the increased ICP on lumbar puncture, usually over 30 cm CSF, with normal CSF constituents. The importance of the diagnosis is that, untreated, the raised ICP puts the optic nerve at risk and can result in significant visual field defects. Treatment is by lumbar puncture, acetazolamide (decreases CSF pressure) and weight loss. Visual field measurement documents progress. Occasionally, surgical drainage is required, using lumboperitoneal shunting.

Safe but unpleasant headaches

The aetiology of these headaches is uncertain, with the exception of trigeminal neuralgia.

Migraine and migraine with aura

Migraine is an episodic headache (Fig. 2a), associated with nausea and a dislike of light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia). This may be preceded by focal neurological symptoms (aura). The headaches are the same regardless of the presence of the aura.

The oral contraceptive can trigger attacks; attacks are more common with menstruation and migraine often changes at the time of the menopause. Migraine usually improves during pregnancy.

Treatment of migraine is at three levels:

Tension-type headache

Tension-type headache is the most common form of headache. The headache can be continuous or episodic and is described as pressure or a tight band around the head (Fig. 2b). The pain usually responds relatively poorly to analgesics but the patient continues to take them. The pain may be related to stress or fatigue, though can lack any clear trigger.

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia (e.g. cluster headache)

The trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are a group of uncommon headaches characterized by severe, unilateral pain, lacrimation, red eye and nasal stuffiness (Fig. 2c). They vary according to gender susceptibility, duration and treatment. The commonest is cluster headache which affects men six times more commonly than women. The bouts of severe orbital pain last from 15 min to 3 h and occasionally a ptosis and Horner’s syndrome develop. They occur frequently, once or more per day, for several weeks before subsiding to recur later, again in clusters. During the headache, the patient is restless and walks about, quite unlike a patient with migraine who will lie still. Alcohol may trigger an attack.

Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia is a sudden severe pain (like a red hot needle) and lasts seconds to minutes, and may be followed by a dull aching pain (Fig. 2d). It occurs in bouts, often many times each day. It can be triggered by touch, movement or cold, sometimes preventing the patient eating or drinking even to the point of dehydration. Trigeminal neuralgia is usually caused by compression of the trigeminal nerve by an ectatic blood vessel. It can also occur in multiple sclerosis.

Other head pains

Ice pick headache – brief sudden severe pain occurring at various sites around the head. A migraine variant, responding to migraine prophylaxis.

Ice pick headache – brief sudden severe pain occurring at various sites around the head. A migraine variant, responding to migraine prophylaxis.