Head and Neck Neoplasia

Basic concepts

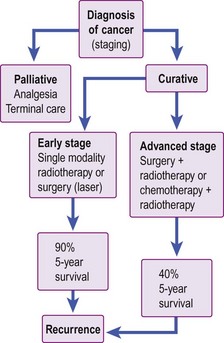

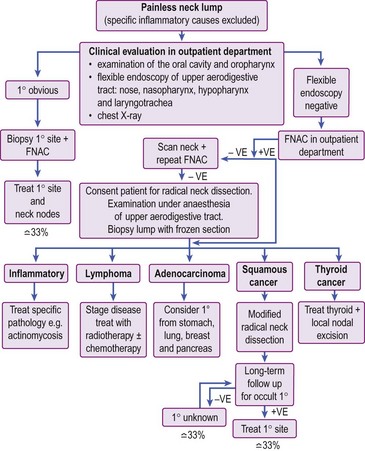

Management of head and neck cancer is dependent on histological diagnosis, staging and grading of the tumour. The patient’s wishes are equally important factors in determining therapy. Some patients may not be fit for aggressive curative treatment and others may refuse treatment. The head and neck oncologist uses surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy as treatment modalities. In general, early cancers are treated with single-modality therapy and advanced cancers require combined modality. A treatment algorithm for head and neck cancer is shown in Figure 4.1.

Aetiological factors

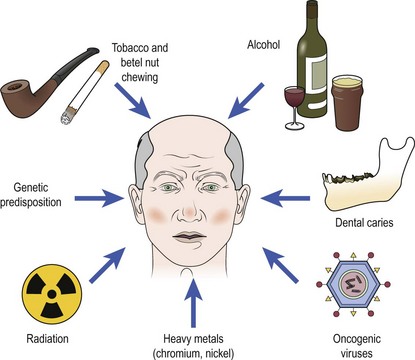

Cancer develops through a complex multifactorial process (Fig. 4.2). The majority of head and neck cancers result from exposure to carcinogens, mainly via tobacco. Chewing tobacco is also carcinogenic and associated with mouth cancer. Alcohol appears to act synergistically with smoking. Betel nut, which is widely chewed in the Indian subcontinent, is a strong carcinogen for mouth cancer, hence the very high incidence of oral cancer in this region. Exposure to ionizing radiation is implicated in thyroid cancer and sarcomas. Oncogenic viruses such as human papilloma virus (HPV) are known to induce tumours in squamous epithelium. HPV is contracted through oral sex and is thought to be the cause of the increase in incidence of oral and oesophageal cancers in younger patients. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is associated with nasopharyngeal cancer and Burkitt’s lymphoma. Heavy metals, such as nickel or chromium, and hardwood dust exposure are important occupational carcinogens. Severe chronic dental caries is thought to predispose to mouth cancer.

Premalignant conditions in head and neck cancer

Clinical manifestations of premalignant conditions are leukoplakia (white patch) or erythroplasia (red patch) which may affect the mucosa (Figs 4.3 and 4.4). These often present as superficial lesions and should be biopsied to determine the grade of dysplasia.

Lichen planus

Erosive lichen planus of the oral cavity (Fig. 4.5) may progress to cancer. The common form of lichen planus, which is benign, is located in a symmetrical distribution on the buccal mucosa and tongue. The erosive variety appears in the floor of the mouth. Biopsy is mandatory to identify the type of lichen planus and to distinguish it from leukoplakia.

Principles of treatment

The treatment options in head and neck neoplasia include:

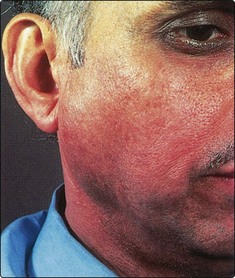

Radiotherapy

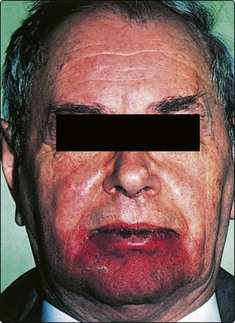

The majority of patients will develop radiation reactions in normal tissue. The skin will invariably show some evidence of treatment (Fig. 4.6). Mucous membrane reactions tend to occur very early, with erythema and ulceration, and may be so severe that nasogastric feeding is required. Fungal infections, particularly by Candida, often compound the mucositis and are not uncommon in the debilitated patient. Prophylactic care with antifungals and anti-inflammatory rinses may be required.

Terminal care

Some patients have no prospect of cure owing to advanced disease or residual or recurrent disease. The dying phase is usually protracted. In order to be able to deal with such situations in a humane manner, the concept of terminal care has evolved. This provides physical and psychological support for patients in the terminal stage of their life (see p. 116).

Basic concepts

Head and neck malignancy uncommonly produces distant metastases.

Head and neck malignancy uncommonly produces distant metastases.

Tobacco and alcohol are the major aetiological factors in development of head and neck malignancy.

Tobacco and alcohol are the major aetiological factors in development of head and neck malignancy.

Any neck mass should only be biopsied after a full examination of the upper air and food passages has been performed to exclude a primary neoplastic process.

Any neck mass should only be biopsied after a full examination of the upper air and food passages has been performed to exclude a primary neoplastic process.

The use of radiotherapy is limited by sensitivity of the surrounding normal tissues, particularly the lens of the eye and the spinal cord.

The use of radiotherapy is limited by sensitivity of the surrounding normal tissues, particularly the lens of the eye and the spinal cord.

Severe radiation reactions may necessitate a temporary halt to the course of radiotherapy.

Severe radiation reactions may necessitate a temporary halt to the course of radiotherapy.

Chemotherapeutic agents appear to enhance the effect of radiotherapy, but their role has not yet been fully evaluated.

Chemotherapeutic agents appear to enhance the effect of radiotherapy, but their role has not yet been fully evaluated.

Neck lumps – introduction

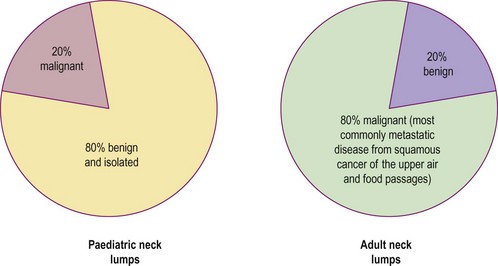

It is useful to consider separately the diagnosis of neck lumps in children and adults. The ‘80 : 20 rule’ applies to malignant and benign causes of neck masses (Fig. 4.7). In the adult it must be remembered that metastatic neck disease may occur from structures below the clavicle (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Infraclavicular sites of malignancy that may cause neck lumps by metastatic spread

| Lung | Kidney |

| Breast | Prostate |

| Stomach | Uterus |

| Pancreas |

Clinical history and examination

In addition to a routine history, specific questions must be posed. The ‘20 : 40 rule’ is useful in considering the diagnostic possibilities of a neck lump (Table 4.2).

| Age (years) | Possible causes of neck lump |

|---|---|

| Less than 20 | Inflammatory neck nodes (e.g. due to tonsillitis) |

| Congenital lesions (e.g. thyroglossal cysts, brachial cyst, midline dermoid, cystic hygroma) | |

| Lymphoma | |

| 20–40 | Salivary gland pathology (calculus, infection, tumour) |

| Thyroid pathology (tumour, thyroiditis, goitre, lymphoma) | |

| Chronic infection (tuberculosis, HIV) | |

| Greater than 40 | Primary or secondary malignant disease |

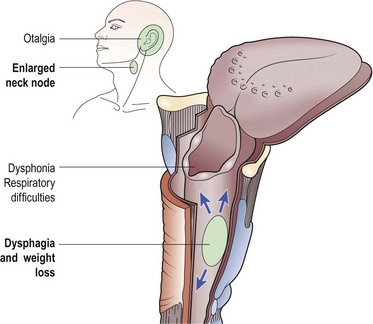

The primary head and neck sites of malignancy may give rise to very specific symptoms including:

Earache may be referred from neoplastic lesions in the upper food passages (see Fig. 1.28, p. 13). Referred otalgia is a poor prognostic sign in head and neck neoplasia.

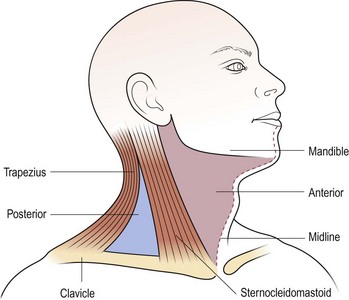

It is important to perform a thorough examination of the head and neck, especially the upper aerodigestive tract, as well as looking for other lumps, e.g. in the liver, spleen or axillae. The scalp should be carefully examined, as a primary malignancy in this site is commonly overlooked as a cause of metastatic neck disease. The precise features of the lump should be noted and, if laterally sited, its position in the triangles of the neck accurately described (Fig. 4.8). This approach is useful as an aid to remembering structures located in the triangles which may give rise to pathology. A mass in the midline is most frequently of thyroid origin. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma may present as unilateral or bilateral metastatic nodes in the posterior triangle of the neck. An isolated mass in the supraclavicular region is likely to be metastatic disease from sites below the clavicle (Table 4.1).

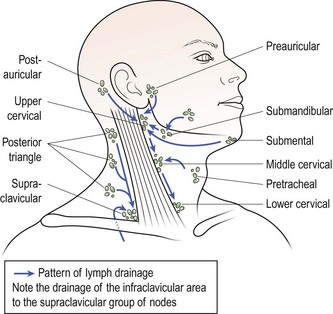

Multiple neck lumps are most likely to be lymph nodes. There are over 100 lymph nodes on each side of the neck, although they tend to be confined to relatively discrete areas rather than evenly distributed (Fig. 4.9).

Investigations

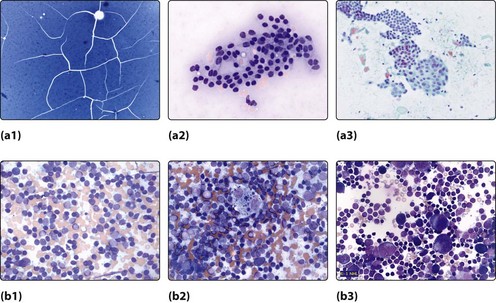

An MDT approach will allow clinical examination, a radiological assessment, usually an ultrasound, followed by Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC). The cytologist will then identify the specimen and decide its nature (Fig. 4.10):

This will direct the management to further and more sophisticated investigations such as CT, MRI or PET scanning (Fig. 4.26, p. 97). In some cases an examination of the upper air and food passages may be required prior to making a definitive diagnosis and formulating a treatment plan.

Biopsy of a neck lump

Neck lumps – introduction

Never biopsy a neck lump without a prior thorough ENT examination of the upper air and food passages.

Never biopsy a neck lump without a prior thorough ENT examination of the upper air and food passages.

Remember the 80 : 20 percentage and the 20 : 40 age rules in the diagnosis of neck lumps.

Remember the 80 : 20 percentage and the 20 : 40 age rules in the diagnosis of neck lumps.

Do not forget infraclavicular sites for metastatic neck lumps, particularly adenocarcinoma.

Do not forget infraclavicular sites for metastatic neck lumps, particularly adenocarcinoma.

Palpate the salivary and thyroid glands and listen for any overlying vascular bruits.

Palpate the salivary and thyroid glands and listen for any overlying vascular bruits.

Multiple neck lumps are almost certainly lymph nodes.

Multiple neck lumps are almost certainly lymph nodes.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology may assist in diagnosis.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology may assist in diagnosis.

Avoid incisional biopsy of a neck lump; if malignant disease is present there is a risk of implantation.

Avoid incisional biopsy of a neck lump; if malignant disease is present there is a risk of implantation.

It is normal for children to have easily palpable lymph nodes in the neck.

It is normal for children to have easily palpable lymph nodes in the neck.

Do not overlook HIV infection as a cause of lymphadenopathy.

Do not overlook HIV infection as a cause of lymphadenopathy.

Neck lumps – paediatric conditions

In the paediatric age group (less than 20 years of age), the majority of neck lumps encountered are benign. They are commonly located anterior to the sternomastoid muscle in the anterior triangle of the neck. An isolated neck lump located in the posterior triangle has a high likelihood of being malignant. The ‘80 : 20 rule’ is useful in assessing the diagnostic possibilities (see Fig. 4.7, p. 90).

Midline neck lumps

Thyroglossal cyst

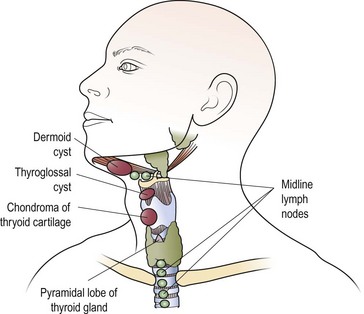

The most common midline mass (Fig. 4.11) in children is a congenital cyst of the thyroglossal duct. Embryologically, the cyst can arise at any site along the route of the thyroglossal duct, extending from the tongue (foramen caecum) to the thyroid gland.

The thyroglossal cyst is most commonly located below the hyoid bone, and moves on both swallowing and tongue protrusion (Figs 4.11 and 4.12). Most cysts are asymptomatic, apart from the presence of a lump, but infection will be associated with pain and swelling. Treatment is by excision, which should include the central portion of the body of the hyoid bone to prevent recurrences. A wedge of tongue muscle is resected with the thyroglossal duct behind the hyoid.

Lateral neck lumps (Table 4.3)

Inflammatory conditions

| Infective | Cervical lymphadenitis |

| Mumps | |

| Tuberculosis | |

| Congenital | Branchial cysts |

| Chemodectoma | |

| Cystic hygroma | |

| Haemangioma | |

| Neoplastic | |

| Primary | Lymphoma |

| Neuroblastoma | |

| Parotid malignancy | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | |

| Secondary | Metastases – nasopharyngeal |

Mumps

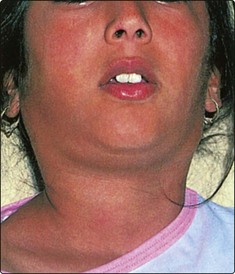

Enlargement of the parotid glands, due to the mumps virus, is extremely common. It is usually a bilateral disease, but unilateral cases can occur (Fig. 4.13). The child has constitutional symptoms of malaise and pyrexia. Rare cases may be complicated by orchitis and encephalitis. Treatment is symptomatic.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis of the cervical lymph nodes is uncommon. Tuberculous nodes are multiple and coalesce, and may form a discharging sinus (Fig. 4.14). Most cases have associated pulmonary tuberculosis. Node biopsy is sometimes required for histological confirmation of diagnosis. Treatment is by combination chemotherapy.

Congenital conditions

Most solitary lateral neck masses in the paediatric age group are congenital in origin.

Branchial arch cysts

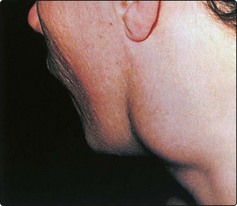

Branchial arch anomalies giving rise to branchial cysts are uncommon. First branchial arch cysts are rare and located anterior to the tragus. True branchial cysts are more frequently encountered and invariably located in the anterior triangle just in front of the sternomastoid (Fig. 4.15). The aetiology is believed to be cystic degeneration in a lymph node. Most of these cysts are lined by lymphoid tissue so that pain and swelling may be experienced with upper respiratory infections. Where a second arch fistula is present a tract may extend to the pharynx, and this must be excised together with the cyst. All brachial arch cysts presenting in patients over 40 years of age should be considered as a possible undiagnosed squamous cell carcinoma.

Cystic hygromas

Cystic hygromas are anomalies of the lymph channels and present as lateral neck swellings. They are soft and irregular, and usually present at birth (Fig. 4.16). Typically, the hygroma enlarges during crying and the Valsalva manoeuvre. They transilluminate brilliantly. Most cystic hygromas have to be removed owing to continued enlargement, particularly as they may encroach onto the major airways. Excision is difficult, as this benign lesion encompasses structures such as the carotid arteries and facial nerve.

Neoplasia

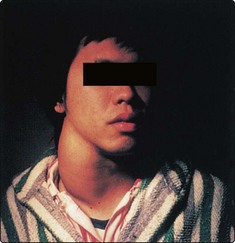

Lymphoma of the Hodgkin’s variety is common. It may present as a unilateral isolated lump in the neck (Fig. 4.17). After histological confirmation, a full evaluation will be required to stage the disease. Treatment is usually radiotherapy in localized disease and chemotherapy with drug combinations in systemic lymphoma.

Rarer primary neoplasia include malignant parotid disease, rhabdomyosarcomas and neuroblastomas.

Neck lumps – paediatric conditions

80% of neck lumps in children are benign and are located in the anterior triangle of the neck.

80% of neck lumps in children are benign and are located in the anterior triangle of the neck.

20% of neck lumps in children are malignant and are usually located in the posterior triangle of the neck.

20% of neck lumps in children are malignant and are usually located in the posterior triangle of the neck.

The most common midline lump in children is the thyroglossal cyst. It moves on swallowing and with tongue protrusion.

The most common midline lump in children is the thyroglossal cyst. It moves on swallowing and with tongue protrusion.

The most common cause of multiple lateral neck lumps in children is cervical lymphadenopathy secondary to infection.

The most common cause of multiple lateral neck lumps in children is cervical lymphadenopathy secondary to infection.

The most common isolated lateral neck lump in children is the branchial cyst.

The most common isolated lateral neck lump in children is the branchial cyst.

Neck lumps – adult conditions

Midline neck lumps

Thyroid masses

It is important to determine whether there is a goitre (diffuse bilateral thyroid enlargement) or a nodular (single) mass within the thyroid (Figs 4.18 and 4.19). Symptoms and signs of hyper- (overactive) and hypo- (underactive) thyroid disease should be sought (Table 4.4). Clinical examination should determine the size and nature of the thyroid mass. Thyroid enlargement may result in compression of either the trachea, causing stridor, or oesophagus, causing dysphagia. Common disorders to affect the thyroid gland include thyroiditis, multinodular goitre, follicular adenoma, thyroid carcinoma and lymphoma.

| Disease | Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperthyroidism | Palpitations | Tachycardia (AF) |

| Weight loss | Exophthalmos | |

| Agitation | Tremor | |

| Sweating | ||

| Hypothyroidism | Tiredness | Bradycardia |

| Weight gain | Loss of eyebrow hair | |

| Poor concentration |

Investigations

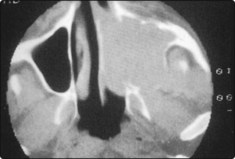

Blood tests should determine thyroid status; a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) test is the first-line investigation. Autoimmune thyroid antibodies should be measured along with thyroglobulin. FNAC should be undertaken to determine the cellular nature of any thyroid nodule. Ultrasound scanning is the first imaging of choice; it will determine whether the thyroid swelling is cystic or solid and will demonstrate whether multiple nodules are present. Ultrasound and FNAC can be combined to increase diagnostic yield. CT scanning is only indicated when tracheal compression or retrosternal extension is suspected (Fig. 4.20).

Lateral neck lumps

Neoplasia

Any neck lump appearing for the first time in an adult over 40 years of age should be treated as metastatic cancer until proven otherwise (Table 4.5). Secondary neck disease from malignancy in the upper aerodigestive tract is very common. The patient frequently gives a long history of alcohol and tobacco abuse. The possibility of a supraclavicular neck mass being metastatic disease from sites below the clavicle should not be overlooked (see Table 4.1, p. 90).

| Type | Condition |

|---|---|

| Neoplasia | Primary cancer |

| Lymphoma | |

| Neurogenic (schwannoma, chemodectoma) | |

| Metastatic cancer | |

| Lymph-node metastasis from head and neck sites | |

| Infection | Glandular fever |

| HIV | |

| Tuberculosis | |

| Parotitis (mumps) | |

| Autoimmune | Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Miscellaneous | Sarcoidosis |

| Branchial cyst | |

| Normal variants | Transverse process of 2nd cervical vertebra (C2) |

| Elongated styloid process | |

| Normal or cervical rib | |

| Tortuous, atherosclerotic carotid artery |

Unilateral painless parotid masses are likely to be neoplastic, the most common lesion being the benign pleomorphic adenoma. Malignant parotid tumours may cause pain and facial weakness owing to involvement of the facial nerve (p. 113). Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma may initially present as an isolated lateral neck lump. However, disease progression leads to multiple matted neck lumps.

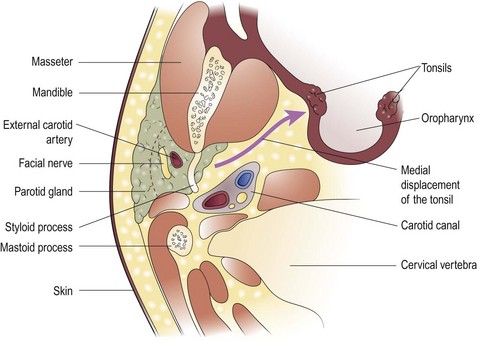

Inflammatory conditions

Acute parotitis, either bacterial or viral, may cause neck swelling (Fig. 4.21). The diagnosis is usually straightforward, provided the full anatomical extent of the parotid is appreciated, including the deep lobe which may enlarge into the oropharynx. An infection of the parapharyngeal space of the neck, usually from dental or oropharyngeal infections, may produce a significant neck swelling in association with a mass in the throat (Fig. 4.22).

Miscellaneous lateral lumps

HIV infection

The primary infection with HIV may produce prodromal symptoms similar to glandular fever (p. 86). Persistent lymphadenopathy syndrome (PLS) is seen in the chronic stage of infection with HIV, with lymph nodes in the neck being commonly enlarged. HIV infection may also present as a cystic swelling in the parotid gland, a ‘lymphoepithelial cyst’.

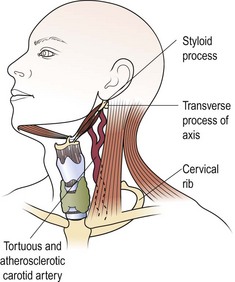

Normal variants

Certain normal bony and cartilaginous structures in the neck may be palpable in some patients and mistaken for lumps (Fig. 4.23). The lateral process of the axis (C2) is often palpable and tender if slight pressure is applied. These features may only be demonstrated on one side of the neck. The styloid process may be elongated and ossified, and therefore palpable as it runs just anterior from the mastoid to the mandible. Normal ribs and, occasionally, an asymptomatic cervical rib may be palpated deep in the supraclavicular fossa. A tortuous atherosclerotic carotid artery in a thin elderly person may be mistaken for a neck mass. It may not be pulsatile, but a bruit is usually audible on auscultation.

Neck lumps – adult conditions

Thyroid lesions are the most common cause of midline lumps in adults.

Thyroid lesions are the most common cause of midline lumps in adults.

The most common lateral neck lump in adults is metastatic malignant disease, usually squamous cell carcinoma from a primary site in the head and neck.

The most common lateral neck lump in adults is metastatic malignant disease, usually squamous cell carcinoma from a primary site in the head and neck.

The symptoms and signs of acute infection with HIV mimic the clinical features of glandular fever.

The symptoms and signs of acute infection with HIV mimic the clinical features of glandular fever.

Neck lumps – management of malignant lumps

The general management of such patients is outlined in Figure 4.24. A full ear, nose and throat (ENT) evaluation will include inspection, radiology and possible biopsy of primary sites in the head and neck. If the primary sites are clear, FNAC may assist in the diagnosis. Otherwise, the mass must be biopsied by excision as incisional biopsies carry the risk of implantation of malignant cells in skin.

Metastatic cervical nodes

Metastatic cervical nodes are clinically assessed and then classified according to the UICC/AJC criteria (Table 4.6). Since the classification is clinically based, it is subject to observer variation. It is also not feasible to decide whether a palpable node contains metastatic cancer or is merely enlarged due to infection. The implication in the classification is that prognosis deteriorates from N1 through to N3 stages. More recently, it appears that the level of metastatic disease in the neck is a better prognostic indicator. Inferiorly placed neck disease has the worst prognosis, with supraclavicular node involvement having the least favourable 5-year survival.

Table 4.6 Classification of regional lymph nodes affected by metastatic carcinoma

| Classification (UICC/AJC) | Clinical assessment |

|---|---|

| N0 | No regional nodes palpable |

| N1 | Mobile ipsilateral nodes |

| N2 | Mobile contralateral or bilateral nodes |

| N3 | Fixed nodes |

UICC: International Union Against Cancer; AJC: American Joint Committee for Cancer Staging.

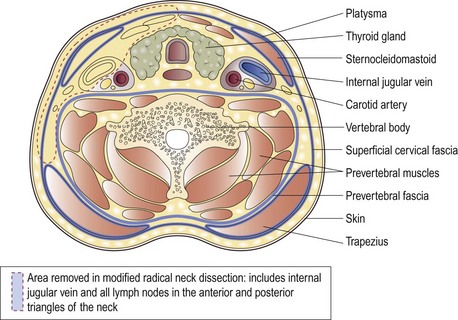

The treatment of metastatic cervical nodes depends to a large degree on whether the primary disease in the head or neck, or in distant sites, has been identified. As a rule, surgery in the form of a modified radical neck dissection is advocated for metastatic neck disease (Fig. 4.25). Radiotherapy may be employed in occult and small nodal metastases, and in palliation of fungating lesions.

N0: clinically negative neck nodes

Impalpable lymph nodes involved in metastatic disease are called occult nodes. There are certain sites in the head and neck, with a rich and frequently decussating lymphatic supply, from which metastatic nodal disease is highly probable (Table 4.7). Although it would be logical therefore to consider performing an elective modified radical neck dissection in occult neck disease, such a policy shows little benefit. It appears that in selected patients, prophylactic radiotherapy markedly diminishes the incidence of recurrent neck disease with little increase in morbidity.

Table 4.7 Sites of primary carcinoma with a high incidence of occult nodes

N1: palpable ipsilateral neck nodes

N1 metastatic disease is subclassified into whether the primary site is known or unknown.

N1 with no known primary site (occult primary)

The histological appearance of the lymph node may give a clue to where the primary malignant site may be located (Table 4.8). Metastatic supraclavicular nodes are likely to have been involved from infraclavicular primary malignant sites.

Table 4.8 The occult primary: how the histology of a malignant node may assist in determining the primary site

| Histology of metastatic neck node | Probable primary malignant sites |

|---|---|

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Head and neck sites: nasopharynx, tonsil, tongue base, supraglottic larynx, floor of mouth, piriform fossa, postcricoid region |

| Adenocarcinoma | Infraclavicular sites: bronchus, stomach, breast, intestine, kidney, prostate, uterus |

| Head and neck sites: ethmoid sinuses and thyroid gland | |

| Undifferentiated or anaplastic carcinoma | Exclude lymphoma by immunocytochemistry |

| Consider the above sites of carcinoma |

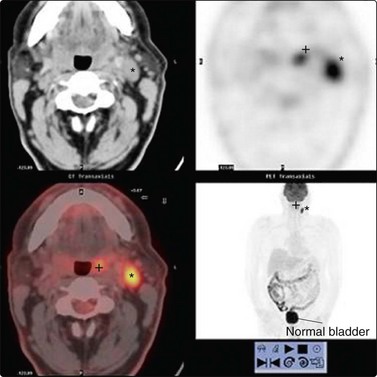

The occult primary in the head and neck is a rare entity. However, if after thorough clinical examination the primary lesion cannot be identified, positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can be useful in identifying the site (Fig. 4.26).

N2: bilateral neck nodes

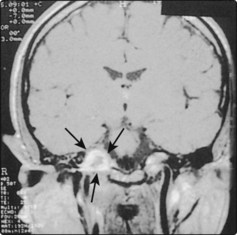

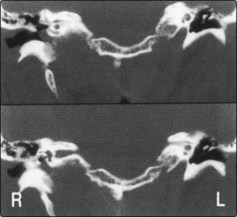

The appearance of bilateral malignant metastatic neck nodes is a very poor prognostic sign. Such an event is more likely in primary tumours of the tongue base and hypopharynx. Serious thought should be given as to whether such patients require active treatment or active palliation. It is feasible to perform bilateral neck dissection as a single rather than staged procedure, preserving one jugular vein. Tying a single internal jugular vein results in a rise in intracranial pressure which is raised even further on tying the second side (Fig. 4.27). Morbidity and mortality related to the huge increase in intracranial pressure may be prevented by modification of the classic radical dissection, and drug intervention.

N3: fixed nodes

Neck lumps – management of malignant lumps

The most common cause of a lateral neck swelling is an enlarged lymph node, usually secondary to inflammatory, lymphomatous or metastatic disease.

The most common cause of a lateral neck swelling is an enlarged lymph node, usually secondary to inflammatory, lymphomatous or metastatic disease.

The most common primary sites of malignant neck nodes are metastatic squamous carcinoma from the head and neck.

The most common primary sites of malignant neck nodes are metastatic squamous carcinoma from the head and neck.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma, particularly if the nodes are low in the neck, may be from infraclavicular sites.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma, particularly if the nodes are low in the neck, may be from infraclavicular sites.

Excisional rather than incisional biopsies of neck nodes should be performed to avoid implanting malignant disease.

Excisional rather than incisional biopsies of neck nodes should be performed to avoid implanting malignant disease.

Occult nodes (primary malignant site known) are defined as impalpable nodes. Prophylactic neck radiotherapy should be considered to control the potential neck disease.

Occult nodes (primary malignant site known) are defined as impalpable nodes. Prophylactic neck radiotherapy should be considered to control the potential neck disease.

N1 nodes should be treated together with the primary site. If the primary site is unknown (occult primary), a thorough investigation and continued follow-up will reveal it in 60% of cases.

N1 nodes should be treated together with the primary site. If the primary site is unknown (occult primary), a thorough investigation and continued follow-up will reveal it in 60% of cases.

The standard surgical procedure for treating malignant nodal disease in the neck is a modified radical neck dissection.

The standard surgical procedure for treating malignant nodal disease in the neck is a modified radical neck dissection.

Laryngeal neoplasia

Benign laryngeal tumours

Benign laryngeal tumours are encountered only infrequently, the most common being the haemangiomata of childhood and respiratory papillomatosis (p. 65).

Paragangliomas (chemodectomas; glomus tumours) may occur in the larynx and usually present as painful lesions causing dysphagia (see Fig. 4.76, p. 115). The diagnosis is confirmed histologically, and the majority require conservative surgery.

Malignant laryngeal tumours

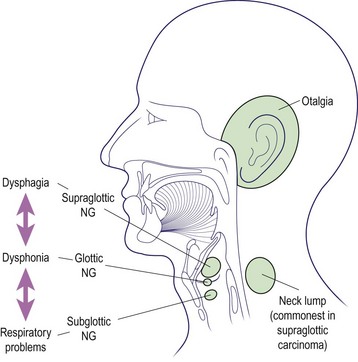

The classification of laryngeal malignant disease is shown in Table 4.9. For descriptive purposes, the larynx is divided into three regions: the supraglottis, glottis and subglottis. It is useful to discuss the management of malignant laryngeal disease according to the region primarily affected. The common symptoms are illustrated by region in Figure 4.28.

Table 4.9 Classification of the primary site of carcinoma of the larynx

| Designation | Description |

|---|---|

| TIS | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Carcinoma within one region |

| T2 | Carcinoma in two regions but with mobile vocal cords |

| T3 | Fixation of vocal cord |

| T4 | Carcinoma beyond the larynx (e.g. thyroid, tongue, hypopharynx) |

The nodal (N) and distant metastasis (M) status will allow formal TNM classification.

Carcinoma in situ

Carcinoma in situ (TIS) is the stage of laryngeal carcinoma that may precede frank invasive malignant disease (Fig. 4.29). Histologically, the carcinoma does not breach the basement membrane. The affected area is excised under microscopic control using either microinstruments or a carbon dioxide laser. Clearly, all lesions should be biopsied before vaporization with the laser beam.

Supraglottic laryngeal carcinoma

The sites of tumour in the supraglottic region (Fig. 4.28) include the lower portion of the epiglottis, false cords, ventricles and arytenoids. A very rich decussating lymphatic supply is present, so the frequency of regional nodal metastases is high and may be bilateral.

Clinical features

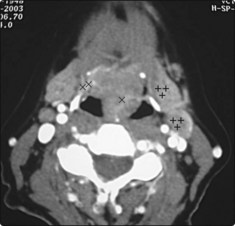

Modern MRI or CT scanning provides excellent images for assessing the extent of the neoplasia (Fig. 4.30). Endoscopic laryngoscopy allows a full assessment of the extent of the disease, and the precise nature of the disease is confirmed by biopsy. The neck should be painstakingly palpated to detect the presence of any metastatic neck nodes.

Glottic laryngeal carcinoma

Clinical features

The earliest symptom of glottic cancer is dysphonia (hoarseness). Any patient with dysphonia persisting for 4 weeks should be seen by an ENT surgeon to have the larynx formally assessed. Other symptoms appear late in the disease process owing to spread beyond the glottis or to extralaryngeal structures (Fig. 4.28).

Transglottic laryngeal carcinoma

Laryngeal neoplasia

The majority of laryngeal lesions are malignant.

The majority of laryngeal lesions are malignant.

60% occur in the glottis and present early due to the onset of dysphonia.

60% occur in the glottis and present early due to the onset of dysphonia.

Dysphonia is usually a late presentation symptom of subglottic and supraglottic malignancy.

Dysphonia is usually a late presentation symptom of subglottic and supraglottic malignancy.

A supraglottic carcinoma may present as a metastatic neck lump.

A supraglottic carcinoma may present as a metastatic neck lump.

TIS (carcinoma in situ) should be treated by regular stripping of the vocal cord or laser cordectomy, with histological review.

TIS (carcinoma in situ) should be treated by regular stripping of the vocal cord or laser cordectomy, with histological review.

Radiotherapy is the primary form of treatment in laryngeal carcinoma without evidence of nodal disease.

Radiotherapy is the primary form of treatment in laryngeal carcinoma without evidence of nodal disease.

Primary surgery to the larynx and neck may be advocated for patients with evidence of metastatic neck disease. Surgery is most commonly reserved for residual or recurrent disease after primary radiotherapy.

Primary surgery to the larynx and neck may be advocated for patients with evidence of metastatic neck disease. Surgery is most commonly reserved for residual or recurrent disease after primary radiotherapy.

Laryngeal surgery and postlaryngectomy rehabilitation

There are essentially two types of procedures for laryngeal cancer: partial or total laryngectomy.

Total laryngectomy

Complications of total laryngectomy

The main problems associated with total laryngectomy are shown in Table 4.10.

Table 4.10 Complications after total laryngectomy

Pharyngocutaneous fistulae

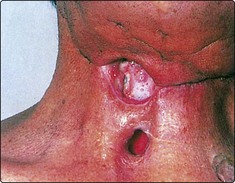

Pharyngocutaneous fistulae are tracts connecting the pharynx to the skin of the neck. They may be multiple and leak saliva (Fig. 4.31). There is an increased risk of developing such fistulae if the surgical technique is poor, preoperative radiotherapy has been given and the patient is poorly nourished. The majority of fistulae will heal spontaneously over a period of weeks. However, those associated with a loss of tissue will require repair with skin or muscle flaps.

Recurrence of disease

Recurrence of disease in the end tracheostome has a poor prognosis (Fig. 4.32). It may be due to implantation of tumour cells during the primary laryngectomy, or a new primary cancer at the stomal site. The majority of such patients will be managed as terminal cases. Palliative radiotherapy and surgery may alleviate the distressing symptoms of respiratory distress and fungating skin mass.

Voice restoration after laryngectomy

Oesophageal speech

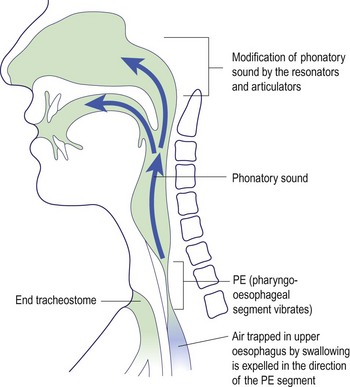

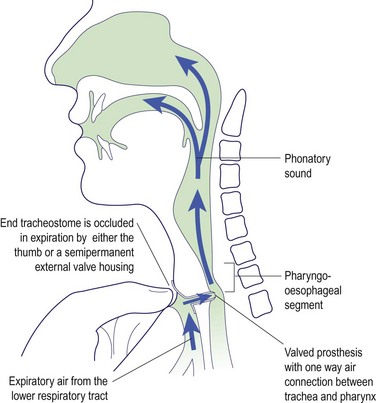

Oesophageal speech is based on a portion of the oesophagus called the pharyngo-oesophageal (PE) segment. It involves the rapid swallowing of air which is trapped in the upper part of the oesophagus (Fig. 4.33). This air reservoir is employed to vibrate the PE segment by controlled contraction of the thoracic and abdominal muscles. The phonatory sound produced is modified in the normal way by the resonators and articulatory mechanisms in the oral cavity and nose. In effect, the oesophagus has replaced the lungs as a small power source for initiating vibration. Only about 20% of laryngectomy patients achieve speech in this way. Oesophageal speech can only be acquired with long-term speech therapy and many patients never achieve a satisfactory quality.

Neoglottic speech

Various surgical techniques employ valved prostheses which are inserted to redirect pulmonary air through the PE segment. The prosthesis is placed in a surgically created fistula connecting the posterior tracheal and anterior oesophageal walls (Fig. 4.34). The one-way valve in the prosthesis allows air to flow into the PE segment when the stoma is occluded during exhalation. More recently, external valve housings have been used to overcome the tedium and inconvenience of finger occlusion. The major complication of surgical prosthetic techniques is the risk of a leak around the tracheo-oesophageal valve, allowing aspiration of food, drink and saliva.

Artificial larynx

Artificial larynxes (Fig. 4.35) work on the principle that air within the vocal tract can be put into vibration by an external battery-powered device. The instrument can be placed either against the skin of the neck or in the oral cavity.

Laryngeal surgery and postlaryngectomy rehabilitation

Total laryngectomy is almost exclusively performed for malignant disease of the larynx.

Total laryngectomy is almost exclusively performed for malignant disease of the larynx.

In total laryngectomy, part of the pharyngo-oesophagus is included in the resection.

In total laryngectomy, part of the pharyngo-oesophagus is included in the resection.

Voice loss is the most severe complication of total laryngectomy.

Voice loss is the most severe complication of total laryngectomy.

Oesophageal speech is produced by expelling air trapped in the upper oesophagus, with a satisfactory result in only about one in five patients.

Oesophageal speech is produced by expelling air trapped in the upper oesophagus, with a satisfactory result in only about one in five patients.

Artificial larynxes are easy to use but produce an unnatural, mechanical sound.

Artificial larynxes are easy to use but produce an unnatural, mechanical sound.

Neoglottic procedures involve the creation of a tracheo-oesophageal connection to utilize pulmonary air to vibrate the PE segment.

Neoglottic procedures involve the creation of a tracheo-oesophageal connection to utilize pulmonary air to vibrate the PE segment.

Surgical voice prostheses are easily inserted, but require considerable perseverance to acquire the skills needed to effectively use and care for them.

Surgical voice prostheses are easily inserted, but require considerable perseverance to acquire the skills needed to effectively use and care for them.

Neoplasia of the oral cavity

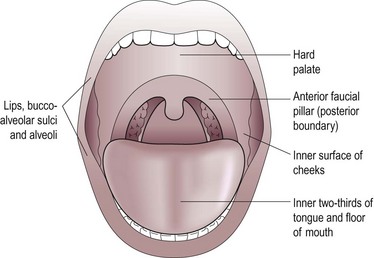

The anatomical contents of the oral cavity are shown in Figure 4.36. These include the upper and lower alveolus, teeth, lips and the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

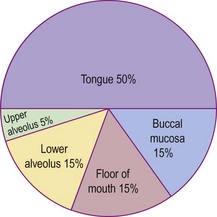

Virtually all oral cavity cancers are of the malignant squamous cell variety. Adenoid cystic carcinoma can arise from minor salivary glands but is rare. The incidence of squamous carcinoma by site within the oral cavity is shown in Figure 4.37.

Premalignant lesions in the oral cavity include leukoplakia and erythroplakia (p. 88). In virtually all neoplasia of the oral cavity one or more of several aetiological factors are present. Smoking and alcohol abuse are very common. Chronic dental infection, e.g. caries, may result in malignant change, as may lesions seen in tertiary syphilis.

Carcinoma of the lip

Clinical features

The appearance of a carcinoma of the lip is usually an ulcer (Fig. 4.38). Included in the differential diagnosis is keratoacanthoma, syphilis and tuberculosis. A biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.

Management

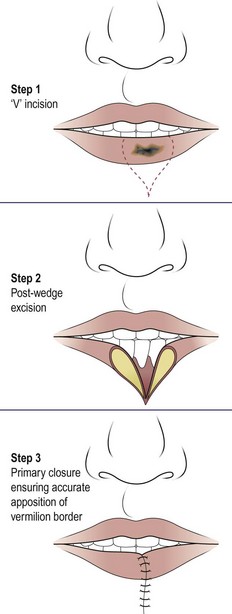

A lip shave and advancement of the vermillion is performed in actinic cheilitis. Any neoplastic lesion requiring less than a third of the lip to be excised can be removed by a modified V incision and primary closure (Fig. 4.39). Larger tumours will require local skin flaps for reconstruction. Radical neck dissection will be necessary if metastatic nodal disease is present. Radiotherapy in small early lesions also produces excellent results, and control may be achieved using the argon laser.

Carcinoma of the tongue

Clinical features

A persistent ulcer, usually painless, is the common presentation (Fig. 4.40). If allowed to grow, the lesion will ultimately cause tongue fixation and invade the mandible. The patient will then experience difficulty in chewing, swallowing and speech. About a third of patients will have a metastatic neck gland at presentation, which may be on the contralateral side of the neck owing to the decussating nature of the lymphatic drainage in this area. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Carcinoma of floor of mouth

Clinical features

Dysphagia and odynophagia (pain on swallowing) are common symptoms. Pain is usually a major feature and signifies deep invasion. There may also be referred otalgia. An orthopantogram or CT scan may reveal bone erosion of the mandible (Fig. 4.41). Biopsy is mandatory for tissue diagnosis and before embarking on major surgery.

Carcinoma of the alveolar ridge

Treatment is along similar lines to that of carcinoma of the floor of mouth.

Carcinoma of the buccal lining

The buccal lining is a very common site for cancer on the Indian subcontinent, probably resulting from metaplastic change included by betel nut chewing. The lesion may be ulcerative or exophytic (Fig. 4.42). A biopsy will confirm the diagnosis. Early small lesions may be successfully excised and primarily sutured. Wider resection will require skin grafting. Radiotherapy should be used in extensive lesions, which are usually incurable owing to invasion of the pterygoid muscle region.

Neoplasia of the oral cavity

The majority of malignant tumours in the oral cavity present as ulcers.

The majority of malignant tumours in the oral cavity present as ulcers.

Syphilis and tuberculosis are now infrequent causes of ulcers in the oral cavity.

Syphilis and tuberculosis are now infrequent causes of ulcers in the oral cavity.

Palpation of a lesion in the oral cavity will yield more information (texture, dimensions, fixity, etc.) than visual inspection.

Palpation of a lesion in the oral cavity will yield more information (texture, dimensions, fixity, etc.) than visual inspection.

Any ulcer in the oral cavity if present for more than 3 weeks must be biopsied to exclude malignant disease.

Any ulcer in the oral cavity if present for more than 3 weeks must be biopsied to exclude malignant disease.

Biopsy is mandatory prior to any surgery.

Biopsy is mandatory prior to any surgery.

Osteoradionecrosis may occur in post-irradiated bone if damaged surgically.

Osteoradionecrosis may occur in post-irradiated bone if damaged surgically.

Soft tissue surgical defects are best replaced so as to maintain mobility in any tongue remnant and to aid mastication and articulation.

Soft tissue surgical defects are best replaced so as to maintain mobility in any tongue remnant and to aid mastication and articulation.

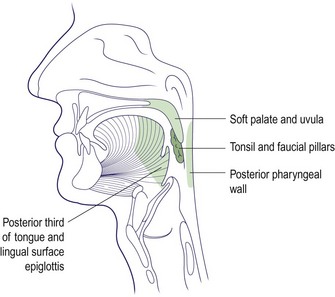

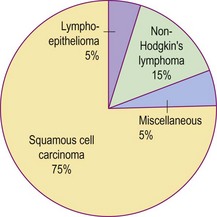

Neoplasia of the oropharynx

The anatomical dimensions of the oropharynx have been previously detailed (p. 56). The major sites comprising the oropharynx are illustrated in Figure 4.43. The majority of tumours are malignant squamous cell carcinomas, but lymphoma and minor salivary gland lesions can also occur (Fig. 4.44). Benign tumours are rarely encountered.

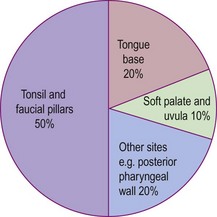

Squamous carcinoma of the oropharynx

Squamous carcinoma of the oropharynx used to be a disease predominantly of the elderly male, with the tonsil and faucial pillars being the site of incidence in 50% of cases (Fig. 4.45). The increased incidence of human papilloma virus (HPV)-associated cancer of the oropharynx has led to younger males and females, who have never smoked, being affected. Owing to the rich lymphatic supply of the oropharynx, the regional lymph nodes are involved in about 60% of cases at the time of presentation.

Clinical features

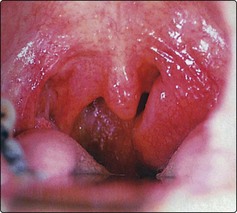

The usual presentation is a history of throat discomfort associated with progressive dysphagia and otalgia. Many patients have a sensation of a ‘lump in the back of the throat’. About 40% present with a metastatic neck node. The tumour is usually apparent as an ulcer on routine examination (Fig. 4.46), but its margins are more clearly determined by palpation and MRI scanning.

Lymphoma of the oropharynx

The oropharynx is the most common extranodal site for lymphomata. These are mostly non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) of the B-cell variety and of high-grade malignancy. T-cell NHL is much less frequent and usually associated with immunosuppressive diseases such as AIDS (p. 86).

Clinical features

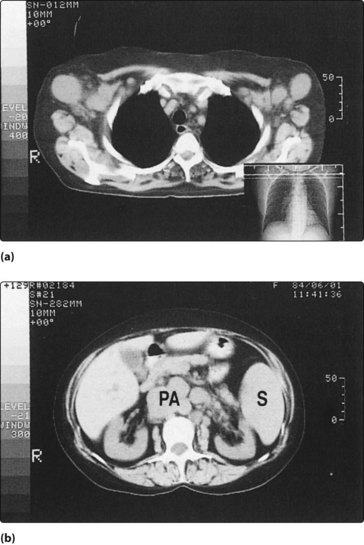

The tonsil is the usual site affected and presents as a smooth unilateral enlargement of this structure (Fig. 4.47). A tonsillectomy will be required, and the specimen examined histologically to determine the cellular immunology and the surface markers. Staging of NHL requires a chest X-ray and CT or MRI of the thorax and abdomen (Fig. 4.48).

Salivary gland tumours of the oropharynx

Management

Neoplasia of the oropharynx

Oropharyngeal cancer may present as a ‘lump in the back of the throat’.

Oropharyngeal cancer may present as a ‘lump in the back of the throat’.

HPV infection is an important cause of oropharyngeal cancer.

HPV infection is an important cause of oropharyngeal cancer.

Virtually all oropharyngeal lesions can be visualized on routine examination.

Virtually all oropharyngeal lesions can be visualized on routine examination.

All oropharyngeal lesions should be palpated. This allows accurate assessment of the extent of the lesion.

All oropharyngeal lesions should be palpated. This allows accurate assessment of the extent of the lesion.

A unilateral enlargement of the tonsil requires excision and histological assessment.

A unilateral enlargement of the tonsil requires excision and histological assessment.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common neoplastic lesion encountered in the oropharynx.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common neoplastic lesion encountered in the oropharynx.

40% of patients with an oropharyngeal carcinoma present with a metastatic neck node.

40% of patients with an oropharyngeal carcinoma present with a metastatic neck node.

The tonsil is the most common site for extranodal lymphomata; the majority of these are of the non-Hodgkin’s B-cell variety.

The tonsil is the most common site for extranodal lymphomata; the majority of these are of the non-Hodgkin’s B-cell variety.

Neoplasia of the hypopharynx

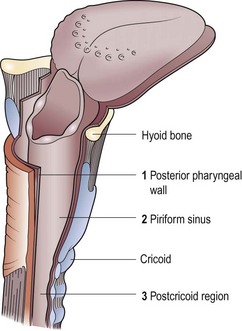

The hypopharynx (laryngopharynx) extends from the hyoid superiorly to the cricoid cartilage inferiorly. It is subdivided into three parts (Fig. 4.49).

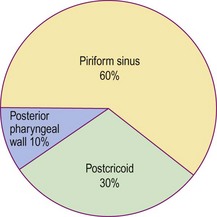

Benign tumours in this region are rare. Virtually all malignant tumours are squamous carcinomas, and the incidence according to site is shown in Figure 4.50. Neck node metastases are very common from primary sites within the hypopharynx, with the piriform fossa having the highest incidence. Postcricoid tumours may metastasize to the mediastinal and paratracheal group of nodes, as well as nodes in the neck.

Hypopharyngeal carcinoma

Paterson–Brown Kelly syndrome

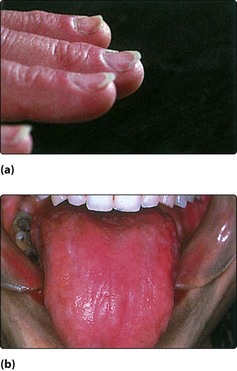

There is a known association between sideropenic dysphagia and postcricoid carcinoma. Paterson and Brown Kelly described a syndrome (also known as Plummer–Vinson) comprising hypochromic microcytic anaemia, glossitis, koilonychia, splenomegaly and a postcricoid web with dysphagia (Fig. 4.51). It was thought the dysphagia resulted from the presence of the postcricoid web or sometimes a stricture. However, some patients do not demonstrate these obstructive lesions and it is thought likely that the dysphagia is due to muscular incoordination.

Haematological abnormalities include a low serum iron and a raised total iron binding capacity. The haemoglobin is frequently low but may be normal. Some patients demonstrate poor vitamin B12 absorption and a low serum vitamin B12. The postcricoid web or a fibrous stricture can be demonstrated radiologically (Fig. 4.52).

Clinical features

The major clinical features of hypopharyngeal neoplasia are summarized in Figure 4.53. True dysphagia is usually a late feature, as the tumour has considerable space in which to grow before causing actual obstructive symptoms. Initially, the only complaint may be odynophagia (pain or discomfort on swallowing) or a feeling of soreness and pricking as food passes through the pharyngo-oesophagus.

Investigations

A barium swallow may show an irregular filling defect of the mucosa (Fig. 4.54). A negative swallow in the presence of persistent feeling of something in the throat requires a formal pharyngo-oesophagoscopy. A chest X-ray may reveal the presence of a second primary cancer or show enlargement of the mediastinum and paratracheal region due to metastatic disease. The lesion should be biopsied and its extent mapped for treatment planning.

Management

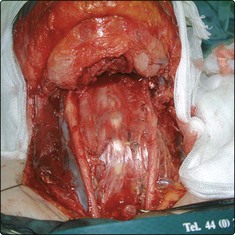

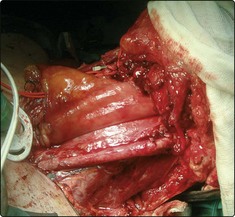

The standard surgical management for advanced hypopharyngeal tumours involves excision of the larynx and pharynx – total laryngopharyngectomy along with a neck dissection, often bilateral (Fig. 4.55). Reconstruction of the pharynx and oesophagus involves microvascular free-tissue transfer with a jejunal (small bowel) segment anastomosed to blood vessels in the neck. This type of surgery requires three surgical teams: one to resect the tumour, one to harvest the bowel from the abdomen and one to perform the reconstruction (Fig. 4.56). This surgery allows the patient to swallow an oral diet.

Prognosis

Neoplasia of the hypopharynx

Sideropenic dysphagia (Paterson–Brown Kelly or Plummer–Vinson syndrome) is associated with the development of postcricoid carcinoma.

Sideropenic dysphagia (Paterson–Brown Kelly or Plummer–Vinson syndrome) is associated with the development of postcricoid carcinoma.

Hypopharyngeal neoplasia tends to present late.

Hypopharyngeal neoplasia tends to present late.

The earliest symptom of hypopharyngeal neoplasia may merely be the feeling of something in the throat, e.g. a crumb or hair.

The earliest symptom of hypopharyngeal neoplasia may merely be the feeling of something in the throat, e.g. a crumb or hair.

Dysphagia is usually severe by the time of presentation.

Dysphagia is usually severe by the time of presentation.

Regional neck metastases are common.

Regional neck metastases are common.

All cases will require a barium swallow and endoscopic biopsy.

All cases will require a barium swallow and endoscopic biopsy.

Radiotherapy should be reserved for small cancers without nodal metastases.

Radiotherapy should be reserved for small cancers without nodal metastases.

A third of patients with hypopharyngeal neoplasia are untreatable.

A third of patients with hypopharyngeal neoplasia are untreatable.

Surgical excision usually necessitates a pharyngolaryngo-oesophagectomy.

Surgical excision usually necessitates a pharyngolaryngo-oesophagectomy.

The swallowing tube is best reconstructed using some form of visceral interposition.

The swallowing tube is best reconstructed using some form of visceral interposition.

Neoplasia of the nasopharynx

The main nasopharyngeal or postnasal space neoplasms are listed in Table 4.11. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is the most common malignant tumour encountered, and the angiofibroma is the only benign tumour of any great importance.

| Malignant | Benign |

|---|---|

| Carcinoma | Angiofibroma |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | |

| Chordoma |

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Aetiology

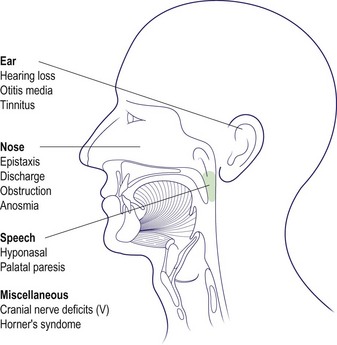

Clinical features

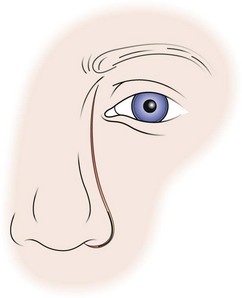

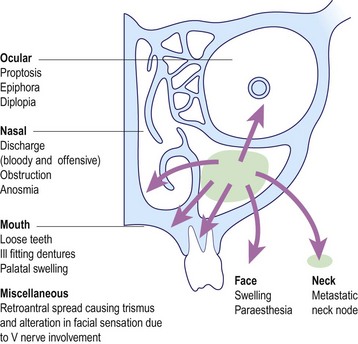

The majority of tumours arise in the fossa of Rosenmüller and can spread in any direction to produce a vast array of potential symptoms and signs (Fig. 4.57). A variety of cranial nerve lesions can occur. The involvement of the trigeminal nerve by superior extension into the foramen ovale manifests as facial pain and altered sensation in the face. Horner’s syndrome (meiosis, ptosis and anhidrosis) may result from involvement of the sympathetic trunk in the carotid sheath.

Investigations

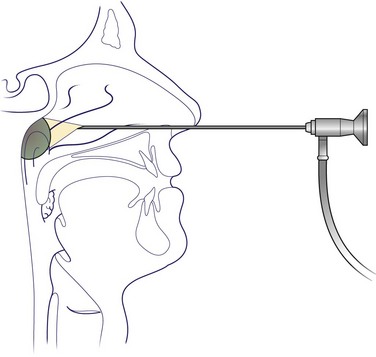

The neoplasm may be seen on routine postnasal space mirror examination. A more valuable and reliable view will be obtained with the flexible rhinolaryngoscope or rigid nasoendoscope (Fig. 4.58). It may be feasible to perform a biopsy in outpatients. All other patients should be subjected to formal biopsy under general anaesthesia.

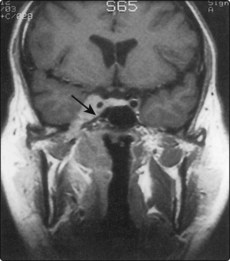

MRI scanning is essential to assess the extent of the disease, particularly its potential extension to the skull base and pharyngeal spaces (Fig. 4.59). MRI is superior to CT at depicting involvement of soft tissue, but inferior to CT in showing bony destruction.

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma

Investigations

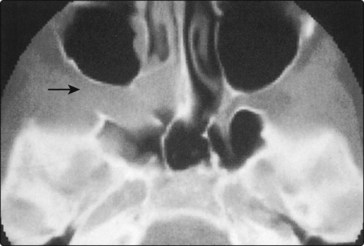

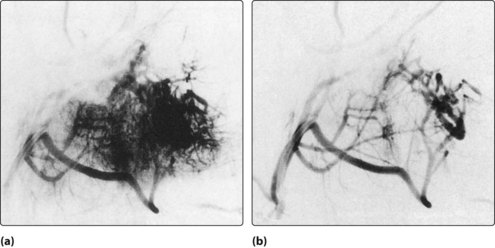

Radiological investigations, MRI and CT, will reveal the nature and extent of the angiofibroma (Fig. 4.60). Angiographic assessment will also allow an opportunity to perform preoperative embolization to reduce the vascularity of the tumour and, hence, minimize blood loss during any subsequent surgical removal (Fig. 4.61).

Other miscellaneous tumours

The chordoma is a very rare, slow-growing malignant tumour arising from the remnant of the notochord. It can expand from its craniocervical site of origin into the nasopharynx and the neighbouring clivus and cervical vertebrae (Fig. 4.62). Radical surgical excision or decompression is required as the tumour is not radiosensitive.

Neoplasia of the nasopharynx

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is most common in people of Chinese extraction.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is most common in people of Chinese extraction.

All adults developing secretory otitis media should have their nasopharynx examined by an ENT specialist.

All adults developing secretory otitis media should have their nasopharynx examined by an ENT specialist.

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas metastasize early and may present as neck nodes.

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas metastasize early and may present as neck nodes.

Unilateral progressive nasal obstruction and bloody nasal discharge are the earliest symptoms of nasopharyngeal cancer.

Unilateral progressive nasal obstruction and bloody nasal discharge are the earliest symptoms of nasopharyngeal cancer.

A massive epistaxis in a young adult may be the presenting feature of a nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.

A massive epistaxis in a young adult may be the presenting feature of a nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.

Adenoidal hypertrophy is NOT a cause of nasal obstruction after puberty.

Adenoidal hypertrophy is NOT a cause of nasal obstruction after puberty.

Radiotherapy is the primary choice of treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Radiotherapy is the primary choice of treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Neoplasia of the nose and paranasal sinuses

Neoplasia of the nose and paranasal sinuses is rare, occurring in about 1% of all malignancies. Benign tumours are more common than the malignant variety (Table 4.12).

| Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|

| Osteoma | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Papilloma: | Adenocarcinoma |

| – squamous cell | Transitional cell carcinoma |

| – transitional cell | Olfactory neuroblastoma |

| Melanoma |

Benign tumours

Squamous papillomata are very common and are located usually in the vestibular skin (Fig. 4.63). They can be cauterized, but any recurrence should be excised and subjected to histological examination to exclude squamous cell carcinoma.

Transitional cell papillomata (inverted papillomata or Ringertz tumour) usually take origin from the lateral nasal wall. Simple intranasal removal is frequently followed by recurrence. The lesion is more effectively excised by a lateral rhinotomy or midface degloving approach (Fig. 4.64). About 10% of the benign transitional cell lesions are associated with squamous carcinoma. It is not possible to be sure whether there has been malignant transformation of the benign lesion, or if the carcinoma has occurred de novo.

Malignant tumours

Aetiology

Smoking is the most important risk factor for nasal cancer. Certain other factors are known to be carcinogenic in the nose and paranasal sinuses (Table 4.13). Hardwood dust is a known factor in the development of adenocarcinoma of the ethmoid sinuses. Inhalation of nickel dust is implicated in nasal squamous cell carcinoma. Radiation exposure of the skin of the nose may induce malignant change. About 10% of cases of benign transitional cell papillomata are associated with transitional cell carcinoma.

Table 4.13 Aetiological factors implicated in cancer of the nose and sinuses

| Smoking | Mustard gas |

| Nickel dust | Radiation |

| Hardwood dust | Snuff |

| Transitional cell papilloma |

Clinical features

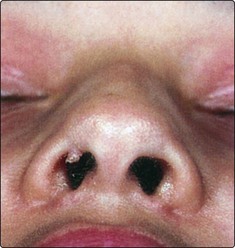

The majority of malignant disease presents in the maxillary antrum, and this serves to illustrate the major symptoms and signs that may occur (Fig. 4.65).

Investigations

Histological confirmation of the malignant process is usually easy owing to the presence of a mass in the nasal cavity. The limits of the disease are most accurately determined by CT scanning, which can be performed in the coronal and axial planes, and provides useful information about soft tissue invasion (Fig. 4.66).

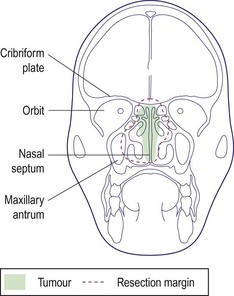

Management

Most malignant disease in the nose and paranasal sinuses may be resected via the lateral rhinotomy approach or by performing a maxillectomy. Any superior extension of the disease into the region of the cribriform plate may be included in the resection by performing a craniofacial resection, i.e. by a combined approach from below and via a craniotomy from above (Fig. 4.67). If the eye is involved, an orbital exenteration will be necessary.

Non-specific (non-healing midline) granulomata

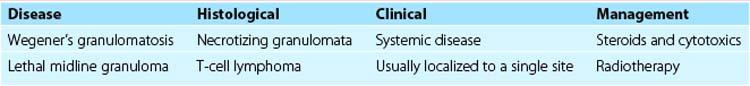

Non-specific granulomata of the nose and paranasal sinuses are lesions that appear to have clinical features of malignancy but are not true neoplasms. Granulomatous lesions of the nose are frequently due to specific infection, e.g. syphilis, tuberculosis or leprosy. However, the non-specific or non-healing midline granulomata have an unknown aetiology, but have now been classified on histological and clinical grounds (Table 4.14) into two varieties:

Table 4.14 Main features of the two types of non-specific, non-healing granulomata of the nose and paranasal sinuses

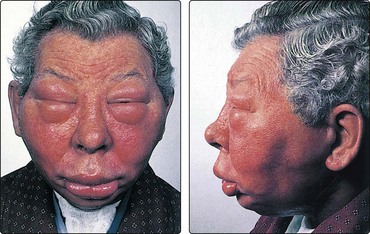

Lethal midline granuloma (midfacial lymphoma)

Lethal midline granuloma is a T-cell lymphoma that results in a slow, progressive destruction of the nose and midface (Fig. 4.68). Treatment involves a curative dose of radiotherapy, combined with surgical excision of necrotic tissue.

Neoplasia of the nose and paranasal sinuses

Unilateral nasal obstruction may be due to tumour, nasal polyps or a deflected septum.

Unilateral nasal obstruction may be due to tumour, nasal polyps or a deflected septum.

A bleeding nasal polyp should be biopsied.

A bleeding nasal polyp should be biopsied.

Neoplasms of the nose and sinuses tend to present late owing to the available space for growth.

Neoplasms of the nose and sinuses tend to present late owing to the available space for growth.

Symptoms and signs may be predominantly nasal, dental, orbital, facial or retroantral depending on the site and direction of spread of malignant disease.

Symptoms and signs may be predominantly nasal, dental, orbital, facial or retroantral depending on the site and direction of spread of malignant disease.

The extent of malignant disease is evaluated by CT scanning but MRI may supersede it.

The extent of malignant disease is evaluated by CT scanning but MRI may supersede it.

The majority of malignant neoplasms will be managed by radiotherapy followed by planned surgery.

The majority of malignant neoplasms will be managed by radiotherapy followed by planned surgery.

Extension of disease into the cribriform plate and anterior cranial fossa can be resected by using a cranial approach in combination with the facial route (cf. craniofacial resection).

Extension of disease into the cribriform plate and anterior cranial fossa can be resected by using a cranial approach in combination with the facial route (cf. craniofacial resection).

Wegener’s granulomatosis is a systemic disease, with both the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidney involved.

Wegener’s granulomatosis is a systemic disease, with both the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidney involved.

Lethal midline granuloma is a T-cell lymphoma of the nose and midface and is treated with radiotherapy.

Lethal midline granuloma is a T-cell lymphoma of the nose and midface and is treated with radiotherapy.

Neoplasia of the salivary glands

Salivary gland neoplasia can be divided, depending on the degree of malignancy, into three varieties, which are summarized in Table 4.15 and discussed below. Rare salivary gland neoplasms include lymphoma, haemangioma and metastatic disease.

Table 4.15 Classification of salivary gland tumours according to behaviour

| Classification | Tumour |

|---|---|

| Benign tumours | Benign pleomorphic adenoma |

| Monomorphic adenoma (adenolymphoma; Warthin’s tumour) | |

| Tumours of variable malignancy | Mucoepidermoid tumour |

| Acinic cell tumour | |

| Malignant tumours | Adenoid cystic carcinoma |

| Malignant pleomorphic adenoma | |

| Adenocarcinoma | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

Benign salivary tumours

Benign pleomorphic adenoma

Virtually all benign pleomorphic adenomas occur in the parotid, with a small number arising in the submandibular gland. The patient usually complains of a painless, slowly enlarging lump in the retromandibular region (Fig. 4.69). The presence of facial pain or paralysis is indicative of a malignant neoplasm. Pleomorphic adenomas have a false capsule, so that simple enucleation is liable to leave residual tumour. About 10% of these adenomas show malignant tendencies, particularly if left for many years.

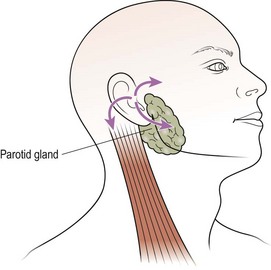

Treatment is by parotidectomy. This usually entails resecting the parotid tissue (in which the adenoma is located) superficial to the facial nerve (Fig. 4.70). Rarely, the tumour may arise in the deep lobe of the parotid and present as an intraoral swelling owing to expansion within the parapharyngeal space. In such cases a total parotidectomy with preservation of the facial nerve is performed. A margin of normal tissue should always be excised to ensure that all tumour projections from the main tumour mass are included in the resection.

Malignant salivary gland tumours

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

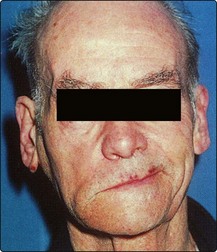

The presenting feature is usually a swelling, often with pain of several months’ duration. Latterly, a neck mass may develop. The facial nerve is invariably compromised in tumours arising in the parotid (Fig. 4.71). The nerve involvement is probably due to the spread of cancer by perineural lymphatics, which is a feature of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Local metastases to lymph nodes are not infrequent. Distant metastases in the lung are also not uncommon.

Complications of salivary gland surgery

The major complications of salivary gland surgery are listed in Table 4.16.

| Procedure | Complications |

|---|---|

| Parotid gland surgery | Facial weakness |

| Anaesthesia of ear | |

| Salivary fistula | |

| Frey’s syndrome (gustatory sweating) | |

| Submandibular gland surgery | Facial weakness |

| Tongue weakness | |

| Anaesthesia of tongue |

Weakness and anaesthesia of the tongue

Weakness and anaesthesia of the tongue are due to trauma to the hypoglossal and lingual nerves, respectively, during submandibular gland excision. These complications are permanent (Fig. 4.72).

Neoplasia of the salivary glands

Benign salivary gland tumours usually present as a slowly enlarging, painless mass.

Benign salivary gland tumours usually present as a slowly enlarging, painless mass.

Facial pain or weakness is invariably due to a malignant salivary tumour.

Facial pain or weakness is invariably due to a malignant salivary tumour.

Parotidectomy will cure most parotid tumours, as they are benign.

Parotidectomy will cure most parotid tumours, as they are benign.

Malignant salivary gland tumours are more likely to occur in the submandibular and minor salivary glands.

Malignant salivary gland tumours are more likely to occur in the submandibular and minor salivary glands.

The facial nerve should be sacrificed if involved by a malignant neoplasm. Immediate nerve grafting or later cross-face anastomosis may be appropriate to overcome the inevitable cosmetic deficit.

The facial nerve should be sacrificed if involved by a malignant neoplasm. Immediate nerve grafting or later cross-face anastomosis may be appropriate to overcome the inevitable cosmetic deficit.

CT and MRI scanning are invaluable in assessing the extent of malignant salivary gland disease, particularly in the parotid and submandibular gland.

CT and MRI scanning are invaluable in assessing the extent of malignant salivary gland disease, particularly in the parotid and submandibular gland.

All patients undergoing parotid and submandibular gland surgery should be informed of the risk of permanent facial weakness.

All patients undergoing parotid and submandibular gland surgery should be informed of the risk of permanent facial weakness.

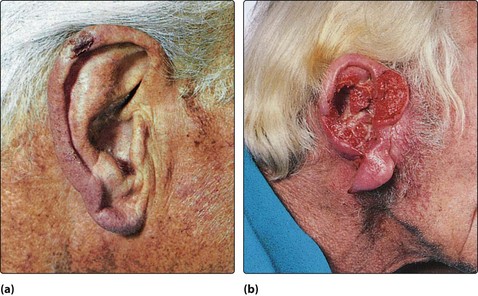

Neoplasia of the ear

Neoplasia of the auricle

Neoplasia of the ear canal

Neoplasms of the ear canal are rare. Those arising in the cartilaginous outer portion of the ear canal offer little resistance to the spread of cancer to the parotid gland and postauricular region (Fig. 4.74). The deeper bony external canal is a more effective barrier to spread, but the cancer may grow medially into the middle ear. Benign growths in the external ear canal are rarely seen.

Neoplasia of the middle ear

Clinical features

The clinical features are illustrated in Table 4.17. The cardinal feature is the change in the symptom complex of what for several years was a simple discharging ear.

| Duration of onset | Clinical feature |

|---|---|

| Years | Mucopurulent otorrhoea |

| Weeks | Bloody otorrhoea |

| Progressive otalgia | |

| Facial paralysis |

Investigations

The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy of aural granulations and polyps. The extent of the disease is determined most suitably with CT scans (Fig. 4.75) and MRI.

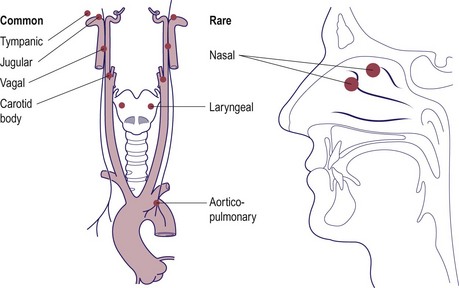

Glomus tumours of the ear

Glomus tumours of the ear arise from the paraganglionic cells (glomus bodies) located at various sites (Fig. 4.76). The glomus tympanicum arises from the region of the promontory in the middle ear and may present as a middle ear polyp. The glomus jugulare tends to invade the middle ear by bony erosion and may spread along the skull base to involve the lower cranial nerve (glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory and hypoglossal). The facial nerve is usually the first and most frequently involved nerve. Intracranial spread is not uncommon as the neoplasm expands.

Clinical features

The most common symptoms (Table 4.18) are hearing loss and pulsatile tinnitus. As these features are only slowly progressive, the patient may delay consultation for many years until one of the more distressing late symptoms such as pain appear. Otoscopic examination will reveal either an obvious middle ear polyp or, if the eardrum is intact, a red or blue swelling behind it (Fig. 4.77). Biopsy may lead to extensive haemorrhage.

Investigations

The extent of the disease is evaluated by CT and MRI scanning, and this will differentiate between a glomus tympanicum and glomus jugulare (Fig. 4.78). Angiography is useful in demonstrating the blood supply of the tumour preoperatively.

Management

Neoplasia of the ear

The majority of auricular tumours can be treated by wedge excision and primary repair.

The majority of auricular tumours can be treated by wedge excision and primary repair.

Ceruminoma is a misnomer. This is a collective term for both benign and malignant tumours arising from apocrine sweat glands.

Ceruminoma is a misnomer. This is a collective term for both benign and malignant tumours arising from apocrine sweat glands.

Carcinoma of the middle ear and mastoid tends to arise in a pre-existing and active chronic suppurative otitis media.

Carcinoma of the middle ear and mastoid tends to arise in a pre-existing and active chronic suppurative otitis media.

Any changes in the character of chronic otorrhoea or the appearance of otalgia, unsteadiness or facial weakness may be due to malignant transformation in the middle ear.

Any changes in the character of chronic otorrhoea or the appearance of otalgia, unsteadiness or facial weakness may be due to malignant transformation in the middle ear.

CT and MRI scanning are essential in the assessment of both middle ear carcinoma and glomus tumours.

CT and MRI scanning are essential in the assessment of both middle ear carcinoma and glomus tumours.

Temporal bone resection for middle ear carcinoma has a high morbidity.

Temporal bone resection for middle ear carcinoma has a high morbidity.

A pulsatile tinnitus and hearing loss are the most common symptoms of glomus tympanicum and jugulare.

A pulsatile tinnitus and hearing loss are the most common symptoms of glomus tympanicum and jugulare.

Biopsy of a glomus tumour may result in torrential haemorrhage.

Biopsy of a glomus tumour may result in torrential haemorrhage.

Radiotherapy may temporarily arrest or considerably slow the growth of glomus tumours.

Radiotherapy may temporarily arrest or considerably slow the growth of glomus tumours.

Terminal care

Management principles

The management of terminal head and neck cancer requires control of symptoms, and moral and psychological support to cope with the prospect of dying (Table 4.19).

Table 4.19 Major symptoms to be controlled in terminal head and neck neoplasia

Pain control

Medical control of pain

be appropriate to the degree of pain

be appropriate to the degree of pain

have a long duration of action

have a long duration of action

It is always important to try to determine the underlying aetiology of any pain. This will allow the correct choice of analgesic, as in some cases a simple increase in narcotics will not produce the desired effect and other preparations may be necessary (Table 4.20).

Table 4.20 Use of drugs in the control of pain in terminal head and neck neoplasia

| Nature/source of pain | Analgesic |

|---|---|

| Lancinating, stabbing | Carbamazepine |

| Nerve compression | Corticosteroid and narcotic |

| Muscle spasm | Diazepam |

| Bone pain | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) |

| Radiotherapy |

Radiotherapy appears to be very effective in abolishing pain due to bone involvement.

Surgical control of pain

More frequently employed are procedures to denervate the peripheral nervous system. The head and neck are served primarily by the trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, vagus and upper cervical nerves. Destructive procedures may thus provide a satisfactory level of pain relief (Table 4.21).

| Site of pain | Nerve involvement |

|---|---|

| Skin of face, scalp, mouth, anterior tongue | Trigeminal |

| Tongue base, tonsil, middle ear | Glossopharyngeal |

| Oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx and oesophagus | Vagus |

| Skin of neck, throat | Upper cervical |

Respiratory difficulties

In cases of anxiety, opiates or sedative antidepressant drugs are particularly useful.

Miscellaneous problems

In the terminal stage of head and neck cancer, the patient may have a number of problems that should be addressed and managed to improve physical and psychological comfort (Table 4.22).

Table 4.22 Distressing problems in terminal head and neck cancer

Necrotic tissue and anaerobic infections combine to produce a foul odour. Treatment of the infection with metronidazole and regular wound toilet usually help to reduce the offensive smell. Fungating tumour is unsightly, frequently foul smelling due to infection and may bleed. Regular toilet is essential, but often these patients die from massive sudden haemorrhage, e.g. carotid blow-out (Fig. 4.79).

Wound and mouth care is mandatory. The regularity of toilet is more important than the methods or materials used (Fig. 4.80). Sponges soaked with antiseptic are very useful in cleaning dried saliva and food debris, and give a refreshing feel to the mouth.

Pressure skin necrosis occurs in cases of terminal cancer, resulting from a combination of poor nutrition, immobility, and loss of control of urinary and bowel sphincters. Good nursing care should prevent problems with pressure areas (Fig. 4.81).

Role of palliative chemotherapy

There are several contraindications to chemotherapy (Table 4.23). It is feasible to improve nutritional status and correct other factors so that previously unsuitable patients may be considered for palliative chemotherapy.

Table 4.23 Contraindications to palliative chemotherapy

The major acute side-effects of chemotherapy are nausea and vomiting, but other toxicities are not uncommon and may prevent continuation of therapy (Table 4.24).

Table 4.24 Toxicity of agents used in palliative chemotherapy

| Toxicity | Chemotherapeutic agent |

|---|---|

| Renal suppression | Cisplatin |

| Methotrexate | |

| Bone marrow suppression | Methotrexate |

| 5-Fluorouracil | |

| Lung fibrosis | Bleomycin |

| Mucositis | Methotrexate |

Terminal care – where?

Terminal care

Advanced head and neck malignancy produces major physical and psychological symptoms.

Advanced head and neck malignancy produces major physical and psychological symptoms.

Pain control is essential in terminal head and neck cancer. This can be provided by medical or surgical means. Breakthrough pain should not be allowed to occur.

Pain control is essential in terminal head and neck cancer. This can be provided by medical or surgical means. Breakthrough pain should not be allowed to occur.

Some degree of relief from dysphagia and respiratory problems can be provided by simple medical means.

Some degree of relief from dysphagia and respiratory problems can be provided by simple medical means.

Radiotherapy should be considered to reduce the symptoms due to bone pain or fungating cancer.

Radiotherapy should be considered to reduce the symptoms due to bone pain or fungating cancer.

Palliative chemotherapy may prolong survival but has major side-effects and is only rarely indicated.

Palliative chemotherapy may prolong survival but has major side-effects and is only rarely indicated.

Consider carefully where the dying patient will be most appropriately cared for – hospital, hospice or home.

Consider carefully where the dying patient will be most appropriately cared for – hospital, hospice or home.