HAZARDOUS AQUATIC LIFE

In general, anyone who gets an infection following a wound acquired in a naturral aquatic environment should be treated with an antibiotic to cover Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species (use dicloxacillin, erythromycin, or cephalexin), and a second antibiotic to cover Vibrio or Aeromonas species (use ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline). An infection from Vibrio or Aeromonas bacteria is more likely in deep puncture wounds, if there is a retained spine (such as from a stingray), and in people who suffer from an impaired immune system (diabetes, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], cancer, chronic liver disease, alcoholism, chronic corticosteroid therapy).

SHARKS

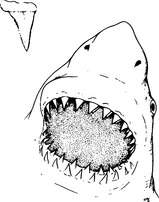

The jaws of the shark contain rows of razor-sharp teeth, which can bite down with extreme force (Figure 184). The result is a wound with loss of tissue that bleeds freely and can lead rapidly to shock (see page 60).

The basic management of a major bleeding wound is described on page 54. Even if a shark bite appears minor, the wound should be washed out and bandaged, and the victim taken to a doctor. Often, the wound will contain pieces of shark teeth, seaweed, or sand debris, which must be removed to avoid a nasty infection. Like other animal bites, shark bites should not be sewn or taped tightly shut, to allow drainage. This helps prevent serious infection. The victim should be started on an antibiotic to oppose Vibrio bacteria (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline).

The skin of many sharks is rough, like sandpaper, and can cause a bad scrape. If this occurs, it should be managed similar to a second-degree burn (see page 108).

Shark Avoidance

1. Avoid shark-infested waters, particularly at dusk and after dark. Do not dive in known shark feeding grounds.

2. Swim in groups. Sharks tend to attack single swimmers.

3. When diving, avoid deep drop-offs, murky water, or areas near sewage outlets.

4. Do not tether captured (speared, for example) fish to your body.

5. Do not corner or provoke sharks.

6. If a shark appears, leave the water with slow, purposeful movements. Do not panic or splash. If a shark approaches you while you are diving in deep water, attempt to position yourself so that you are protected from the rear. If a shark moves in, attempt to strike a firm blow to the snout.

7. If you are stranded at sea and a rescue helicopter arrives to extract you from the water, exit the water at the earliest opportunity.

BARRACUDAS

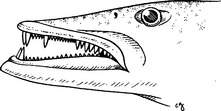

Barracudas may bite victims and create nasty wounds with their long canine-like teeth (Figure 185). These wounds are managed similar to shark bites (see above). Because barracudas seem to be attracted to shiny objects, the swimmer, boater, or diver is advised to not wear bright metallic objects, particularly not a barrette in the hair or anklet dangled on a leg near the surface from a boat or dock.

MORAY EELS

Although they look quite ferocious, moray eels (Figure 186) seldom attack humans, unless provoked. They have muscular jaws equipped with sharp fanglike teeth, which can inflict a vicious bite. A moray tends to bite and hold on; in some instances, it is necessary to break the eel’s jaws to get it to release.

A moray bite should be managed similar to a shark bite (see page 354). Even if the bite is very small, it should be examined by a physician, to be sure that all tooth fragments have been removed. If the bite is more than superficial and on the hand, on the foot, or near a joint, the victim should be started on an antibiotic (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline) to oppose Vibrio bacteria. Avoid sewing or otherwise tightly closing a moray bite unless absolutely necessary.

SPONGES

Sponges handled directly from the ocean can cause two types of skin reaction. The first is an allergic type similar to that caused by poison oak (see page 234), with the difference that the reaction generally occurs within an hour after the sponge is handled. The skin becomes red, with burning, itching, and occasional blistering. The second type of reaction is caused by small spicules of silica from the sponges that are broken off and embedded in the outermost layers of the skin. This causes irritation, redness, and swelling. When large skin areas are involved, the victim may complain of fever, chills, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, and muscle cramps.

1. Soak the affected skin with white vinegar (5% acetic acid) for 15 minutes. This may be done by wetting a gauze pad or cloth with vinegar and laying it on the skin.

2. Dry the skin, and then apply the sticky side of adhesive tape to the skin and peel it off. This will remove most sponge spicules that are present. An alternative is to apply a thin layer of rubber cement or a commercial facial peel, let it dry and adhere to the skin, and then peel it off.

3. Repeat the vinegar soak for 15 minutes or apply rubbing (isopropyl 40%) alcohol for 1 minute.

4. Dry the skin, and then apply hydrocortisone lotion (0.5% to 1%) thinly twice a day until the irritation is gone. Do not use topical steroids before decontaminating with vinegar; this might worsen the reaction.

5. If the rash worsens (blistering, increasing redness or pain, swollen lymph glands), this may indicate an infection, and the victim should be started on an antibiotic to oppose Vibrio bacteria (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline). If the rash is persistent but there is no sign of infection, a 7-day course of oral prednisone in a tapering dose (for a 150 lb, or 68 kg, person, begin with 70 mg and decrease by 10 mg per day) may be helpful. Corticosteroids should always be taken with the understanding that a rare side effect is serious deterioration of the head (“ball” of the ball-and-socket joint) of the femur, the long bone of the thigh.

JELLYFISH

The dreaded box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) (Figure 187) of northern Australia and the Indo-Pacific contains one of the most potent animal venoms known. A sting from one of these creatures can induce death in minutes from cessation of breathing, abnormal heart rhythms, and profound low blood pressure (shock). A sting from the Irukandji (Carukia barnesi) causes a syndrome of muscle spasm (back pain), sweating, nausea and vomiting, high blood pressure, and perhaps death.

Be prepared to treat an allergic reaction following a jellyfish sting! (See page 66.)

The following therapy is recommended for all unidentified jellyfish and other creatures with stinging cells, including the box jellyfish, Portuguese man-of-war (“bluebottle”) (Figure 188), Irukandji, fire coral (Figure 189), stinging hydroid, sea nettle, and sea anemone (Figure 190):

1. If the sting is thought to be from the box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri), immediately flood the wound with vinegar (5% acetic acid). Keep the victim as still as possible. Continually apply the vinegar until the victim can be brought to medical attention. If you are out at sea or on an isolated beach, allow the vinegar to soak the tentacles or stung skin for 10 minutes before you attempt to remove adherent tentacles or further treat the wound. In Australia, surf lifesavers (lifeguards) may carry antivenom, which is given as an intramuscular injection at the first-aid scene. The pressure immobilization technique is no longer recommended as a therapy for jellyfish stings.

2. For all other stings, if a topical decontaminant (vinegar or isopropyl [rubbing] alcohol) is available, pour it liberally over the skin or apply a soaked compress. (Some authorities advise against the use of alcohol on the theoretical grounds that it has not been proven beyond a doubt to help. However, many clinical observations support its use. Since not all jellyfish are identical, it is extremely helpful to know ahead of time what works for the stingers in your specific geographic location.) Vinegar may not work as well to treat sea bather’s eruption (see page 236); a better agent may be a solution of papain (such as unseasoned meat tenderizer—see below for precaution about duration of therapy). For a fire coral sting, citrus (e.g., fresh lime) juice that contains citric, malic, or tartaric acid may be effective. Topical lidocaine 4% may effectively numb a jellyfish sting, but may not lesson the envenomation.

Figure 188 Portuguese man-of-war (“bluebottle”), with a close-up of stinging cells located on the tentacles.

Until the decontaminant is available, you can rinse the skin with seawater. Do not rinse the skin gently with fresh water or apply ice directly to the skin, as these may worsen the envenomation. A brisk freshwater stream (forceful shower) may have sufficient force to physically remove the microscopic stinging cells, but nonforceful application is more likely to cause the cells to fire, increasing the envenomation. A nonmoist ice or cold pack may be useful to diminish pain, but take care to wipe away any surface moisture (condensation) before the application. Recent observations from Australia suggest that hot (nonscalding) water application or immersion may diminish the sting of the Portuguese man-of-war from that part of the world. The generalization of this observation to treatment of other jellyfishes, particularly in North America, should not automatically be assumed, because of the fact that application of fresh water worsens certain envenomations.

3. Apply soaks of vinegar or rubbing alcohol for 30 minutes or until pain is relieved. Baking soda powder or paste is recommended to detoxify the sting of certain sea nettles, such as the Chesapeake Bay sea nettle. If these decontaminants are not available, apply soaks of dilute (quarter-strength) household ammonia. A paste made from unseasoned meat tenderizer (do not exceed 15 minutes of application time, particularly not on the sensitive skin of small children) or papaya fruit may be helpful. These contain papain, which may also be quite useful to alleviate the sting from the thimble jellyfish that causes sea bather’s eruption (see page 236). Do not apply any organic solvent, such as kerosene, turpentine, or gasoline. While likely not harmful, urinating on a jellyfish, or any other marine, sting has never been proven to be effective.

4. After decontamination, apply a lather of shaving cream or soap and shave the affected area with a razor. In a pinch, you can use a paste of sand or mud in seawater and a clamshell.

5. Reapply the vinegar or rubbing alcohol soak for 15 minutes.

6. Apply a thin coating of hydrocortisone lotion (0.5% to 1%) twice a day. Anesthetic ointment (such as lidocaine hydrochloride 2.5% or a benzocaine-containing spray) may provide short-term pain relief.

7. If the victim has a large area involved (an entire arm or leg, face, or genitals), is very young or very old, or shows signs of generalized illness (nausea, vomiting, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, and the like), seek help from a doctor. If a child has placed tentacle fragments in his mouth, have him swish and spit whatever potable liquid is available. If there is already swelling in the mouth (muffled voice, difficulty swallowing, enlarged tongue and lips), do not give anything by mouth, protect the airway (see page 22), and rapidly transport the victim to a hospital.

To prevent jellyfish stings, an ocean bather or diver should wear, at a minimum, a synthetic nylon-rubber (Lycra [DuPont]) dive skin. Safe Sea Sunblock with Jellyfish Sting Protective Lotion (www.buysafesea.com), which is both a sunscreen and a jellyfish sting inhibitor, has been shown to be effective in preventing stings from many jellyfish species.

CORAL AND BARNACLE CUTS

1. Scrub the cut vigorously with soap and water, and then flush the wound with large amounts of water.

2. Flush the wound with a half-strength solution of hydrogen peroxide in water. Rinse again with water.

3. Apply a thin layer of bacitracin or mupirocin ointment, or mupirocin cream, and cover with a dry, sterile, nonadherent dressing. If no ointment or dressing is available, the wound can be left open. Thereafter, it should be cleaned and redressed twice a day.

4. If the wound shows signs of infection (extreme redness, pus, swollen lymph glands) within 24 to 48 hours after the injury, start the victim on an antibiotic to oppose Vibrio bacteria (e.g., ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline), as well as an antibiotic to oppose Staphylococcus bacteria (e.g., dicloxacillin or cephalexin).

SEA URCHINS

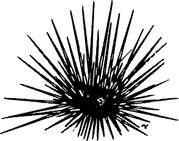

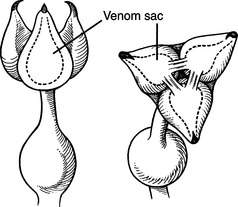

Some sea urchins are covered with sharp venom-filled spines (Figure 191) that can easily penetrate and break off into the skin, or with small pincer-like appendages (Figure 192) that grasp the victim and inoculate him with venom from a sac within the pincer. Sea urchin punctures or stings are painful wounds, most often of the hands or feet. If a person receives many wounds simultaneously, the reaction may be so severe as to cause difficulty in breathing, weakness, and collapse. The treatment for sea urchin wounds is as follows:

1. Immerse the wound in nonscalding hot water to tolerance (110°F to 113°F, or 43.3°C to 45°C). This frequently provides pain relief. Administer appropriate pain medicine.

2. Carefully remove any readily visible spines. Do not dig around in the skin to fish them out—this risks crushing the spines and making them more difficult to remove. Do not intentionally crush the spines. Purple or black markings in the skin immediately after a sea urchin encounter do not necessarily indicate the presence of a retained spine fragment. Such discoloration is more likely dye leached from the surface of a spine, commonly from a black urchin (Diadema spp.). The dye will be absorbed over 24 to 48 hours, and the discoloration will disappear. If there are still black markings after 48 to 72 hours, a spine fragment is likely present.

3. If the sting is caused by a species with pincer organs, use hot-water immersion, and then apply shaving cream or a soap paste and shave the area.

4. Seek the care of a physician if you feel that spines have been retained in the hand or foot, or near a joint. They may need to be removed surgically, to minimize infection, inflammation, and damage to nerves or important blood vessels.

5. If the wound shows signs of infection (extreme redness, pus, swollen lymph glands) within 24 to 48 hours after the injury, or if the spine is felt to have penetrated into a joint, start the victim on an antibiotic to oppose Vibrio bacteria (e.g., ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline), as well as an antibiotic to oppose Staphylococcus bacteria (e.g., dicloxacillin or cephalexin).

6. If a spine puncture in the palm of the hand results in a persistent swollen finger without any sign of infection (fever, redness, swollen lymph glands in the elbow or armpit), it may become necessary to treat a 150 lb, or 68 kg, victim with a 7-day course of oral prednisone in a tapering dose (begin with 70 mg and decrease by 10 mg per day). Corticosteroids should always be taken with the understanding that a rare side effect is serious deterioration of the head (“ball” of the ball-and-socket joint) of the femur, the long bone of the thigh.

STARFISH

The crown of thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) is a particularly venomous starfish found in tropical oceans worldwide (Figure 193). It carries sharp and rigid spines that may grow to 3 in (7.5 cm) in length. The cutting edges easily penetrate a diver’s glove and cause a very painful puncture wound with copious bleeding and slight swelling. Multiple puncture wounds may lead to vomiting, swollen lymph glands, and brief muscle paralysis.

The treatment is similar to that for a sea urchin puncture (see page 362). Immerse the wound in nonscalding hot water to tolerance (110°F to 113°F or 43.3°C to 45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes. This frequently provides pain relief. Administer appropriate pain medicine. Carefully remove any readily visible spines. If there is a question of a retained spine or fragment, seek the assistance of a physician.

CUCUMBERS

Sea cucumbers (Figure 194) are sausage-shaped creatures that produce a liquid called holothurin, which is a contact irritant to the skin and eyes. Because some sea cucumbers dine on jellyfish, they may excrete jellyfish stinging cells and venom as well. Therefore, anyone who sustains a skin irritation from handling a sea cucumber may benefit from the treatment for jellyfish stings described beginning on page 358. If the eyes are involved, they should be irrigated with at least a quart (liter) of water, and immediate medical attention should be sought. If the victim is out at sea, treat the eye injury as a corneal abrasion (see page 180).

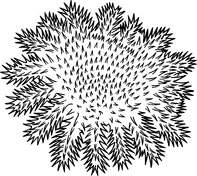

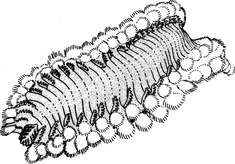

BRISTLEWORMS

Bristleworms are small, segmented marine worms covered with chitinous bristles arranged in soft rows around the body (Figure 195). When a worm is stimulated, its body contracts and the bristles are erected. Easily detached, they penetrate skin like cactus spines and are difficult to remove. Some marine worms are also able to inflict painful bites.

Remove all large visible bristles with tweezers. Then gently dry the skin, taking care to avoid breaking or embedding the spines farther into it. Apply a layer of adhesive tape, rubber cement, or a facial peel to remove the residual smaller spines. If the residual inflammation is significant, the victim may benefit from the administration of topical hydrocortisone 1% lotion.

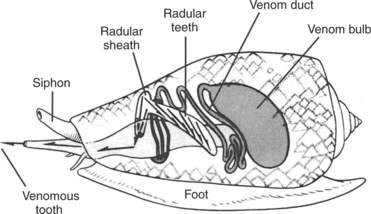

CONE SNAILS (SHELLS)

Cone snails (shells) are beautiful, yet potentially lethal, cone-shaped mollusks that carry a highly developed venom apparatus, consisting of a rapid-acting poison that is injected by means of a dartlike, barbed tooth (Figure 196). The venom causes a mild sting (puncture wound) that initially is characterized by bee sting–like pain or, rarely, numbness and blanching. This is rapidly followed by numbness and tingling at the wound site, around the mouth and lips, and then all over the body. If the envenomation is severe, the victim is afflicted with muscle paralysis, blurred vision, and breathing failure. A sting can be fatal.

There is no antivenom for a cone shell envenomation. While many first-aid remedies (such as hot-water immersion, surgical excision of the sting site, and injection of a local anesthetic) have been recommended, the one that makes the most sense is the pressure immobilization technique (see page 350) to contain the venom until the victim can be brought to advanced medical attention. Be prepared to offer the victim assistance for breathing (see page 29).

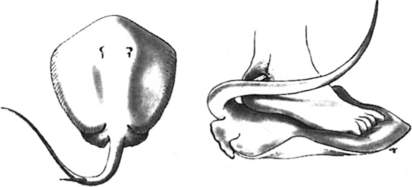

STINGRAYS

A stingray does its damage by lashing upward in self-defense with a muscular tail-like appendage, which carries up to four sharp, swordlike stings (Figure 197). The stings are supplied with venom, so that the injury created is both a deep puncture or laceration and an envenomation. The pain from a stingray wound can be excruciating and accompanied by bleeding, weakness, vomiting, headache, fainting, shortness of breath, paralysis, collapse, and occasionally, death. Most wounds involve the feet and legs, because unwary waders and swimmers tread on the creatures hidden in the sand. If a person is struck by a stingray, immediately do the following:

1. Rinse the wound with whatever clean water is available. Immediately immerse the wound in nonscalding hot water to tolerance (110°F to 113°F, or 43.3°C to 45°C). This may provide some pain relief. Generally, it is necessary to soak the wound for 30 to 90 minutes. Gently extract any obvious piece of stinger, unless it is felt to have penetrated into a location (e.g., chest, neck, abdomen, or groin) where it may have cut and is now occluding a large blood vessel, such as the heart or a major artery or vein. In such a case, leave the stinger in place, regardless of pain, and rush the victim to a hospital.

2. Scrub the wound with soap and water. Do not try to sew or tape it closed; doing so could promote a serious infection.

3. Apply a dressing and seek medical help. If more than 12 hours will pass before a doctor can be reached, start the victim on an antibiotic (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline) to oppose Vibrio bacteria.

Avoidance of Stingray Injuries

1. Always shuffle your feet when wading in stingray waters.

2. Always inspect the bottom before resting a limb in the sand.

3. Never handle a stingray unless you know what you are doing. Even seemingly “domesticated” stingrays, such as those at “Stingray City” off Grand Cayman Island in the British West Indies, have bitten victims with their grinding plate mouths, resulting in serious bite wounds, when handled.

4. Do not approach a stingray within striking distance of its barbed appendage.

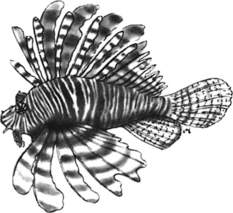

SCORPIONFISH

Scorpionfish include zebrafish (lionfish, turkeyfish) (Figure 198), scorpionfish, and stonefish. They possess dorsal, anal, and pelvic spines that transport venom from venom glands into puncture wounds. Common reactions include redness or blanching, swelling, and blistering (lionfish). The injuries can be extremely painful and occasionally life threatening. The treatment is the same as that for a stingray wound. Soaking the wound in nonscalding hot water to tolerance (110°F to 113°F, or 43.3°C to 45°C) may provide dramatic relief of pain from a lionfish sting, is less likely to be curative for a scorpionfish sting, and may have little effect on the pain from a stonefish sting, but it should be undertaken nonetheless, because the heat may perhaps destroy some of the harmful proteins contained in the venom. If the victim appears intoxicated or is weak, vomiting, short of breath, or unconscious, seek immediate advanced medical aid. Scorpionfish stings frequently require weeks or months to heal, and therefore require the attention of a physician. There is an antivenom available to physicians to help manage the sting of the dreaded stonefish.

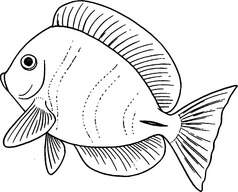

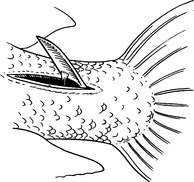

SURGEONFISH

Surgeonfish are tropical reef fish that carry one or more retractable jackknife-like skin appendages on either side of the tail (Figure 199). When a fish is threatened, the appendage(s) is extended, where it serves as a blade to inflict a cut (Figure 200). The appendage may carry venom, which contributes to the pain.

OCTOPUSES

Octopus bites are rare. A nonvenomous octopus bite causes a local irritation that does not require any special therapy, other than wound cleansing and observation for infection. However, a bite from the Indo-Pacific blue-ringed or spotted octopus inoculates the victim with a substance extremely similar to tetrodotoxin, one of the most potent poisons (also found in pufferfish—see page 371) found in nature.

Most victims are bitten on the hand or arm as they handle the creature or “give it a ride.” The bite consists of one or two small puncture wounds, and may go unnoticed. Otherwise, there is a small amount of discomfort, described as a minor ache, slight stinging, or pulsating sensation. Occasionally, the site is initially numb, followed in 5 to 10 minutes by discomfort that may spread to involve the entire limb. By far the most common local reaction is the absence of symptoms, a small spot of blood, or a tiny blanched area.

First aid is the pressure immobilization technique (see page 350). Be prepared to provide artificial respiration (see page 29) until the victim can be brought to advanced medical attention. If oxygen (see page 431) is available, it should be administered by facemask at a flow rate of 10 liters per minute.

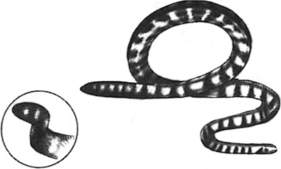

SEA SNAKES

Sea snakes are the most abundant reptiles on earth, though they are found only in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. They can attain a length of 9 ft (2.7 m) and are equipped with a paddle-like tail that allows them to swim forward and backward with considerable speed and agility (Figure 201).

The diagnosis of sea snake envenomation is determined as follows:

1. Unless you are handling a snake (commonly, fishermen emptying nets), you must be in the water to be bitten by a sea snake. The animals cannot move easily on land and do not survive very long there. However, you must be cautious when exploring regions of tidal variation, particularly in mangrove vegetation or near inlets where snakes breed.

2. Sea snake bites rarely cause much pain at the bite site.

3. Fang marks. These are like pinholes and may number from one to four (rarely, up to 20).

4. If symptoms do not occur within 6 to 8 hours of the bite, significant poisoning has not occurred. The symptoms include weakness, paralysis, lockjaw, drooping eyelids, difficulty speaking, and vomiting. Later, the victim will develop darkened urine and difficulty breathing.

If a person is bitten by a sea snake, seek immediate medical attention, and immediately implement the pressure immobilization technique (see page 350). The definitive therapy is similar to that for a land snakebite—namely, administration in a hospital of the proper antivenom.

SKIN RASHES CAUSED BY AQUATIC PLANTS (SEAWEED DERMATITIS) OR CREATURES (SEA BATHER’S ERUPTION, SWIMMER’S ITCH)

POISONINGS FROM SEAFOOD

Scombroid Poisoning

Scombroid poisoning is caused by improper preservation (inadequate refrigeration or drying) of fish in the family Scombridae, which includes tuna, mackerel, bonito, skipjacks, and wahoo. Nonscombroid fish that can also cause this syndrome include mahi-mahi (dolphinfish), anchovies, sardines, and Australian ocean salmon. Most of these fish are dark fleshed. When they are not preserved properly, bacteria break down chemicals in the flesh to produce the chemical histamine, which causes an allergic-type reaction in the victim. Although the fish may have a peppery or metallic taste and “dull” appearance, they may also have normal color, flavor, and appearance. Tuna burgers may be seasoned and mask any abnormal taste.

Minutes after eating the fish, the victim becomes flushed, with itching, nausea and sometimes vomiting, diarrhea, low-grade fever, abdominal pain, and the development of hives (see page 238). Occasionally, a victim will develop low blood pressure and become weak and short of breath, sometimes with wheezing. The reaction is similar to that seen with monosodium glutamate (MSG) sensitivity (“Chinese food syndrome”). Treatment is the same as for an allergic reaction (see page 66). If the victim does not improve with diphenhydramine (Benadryl), he may benefit from cimetidine (Tagamet) 300 mg or fexofenadine (Allegra) 60 mg by mouth. Administer the chosen antihistamine every 6 to 8 hours until symptoms resolve—generally, within 12 to 24 hours.

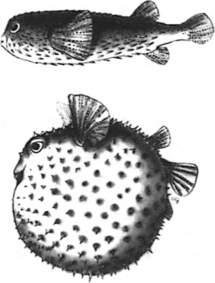

Puffer Poisoning

Certain puffers (blowfish, globefish, swellfish, porcupinefish [Figure 202], and so on) contain tetrodotoxin, one of the most potent poisons in nature. These fish are prepared as a delicacy (fugu) in Japan by specially trained and licensed chefs. The toxin is found in the entire fish, with greatest concentration in the liver, intestines, reproductive organs, and skin. After the victim has eaten the fish, symptoms can occur as quickly as 10 minutes later or be delayed by a few hours. These include numbness and tingling around the mouth, light-headedness, drooling, sweating, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, weakness, difficulty walking, paralysis, difficulty breathing, and collapse. Many victims die.

If someone is suffering from puffer poisoning, immediately transport him to a hospital. Pay attention to his ability to breathe, and assist his breathing if necessary (see page 29). Unfortunately, there is no antidote, and the victim will need sophisticated medical management until he metabolizes the toxin. Eating puffers, unless they are prepared by the most skilled chefs, is dietary Russian roulette.

Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning

Paralytic shellfish poisoning is caused by eating shellfish that contain concentrated toxins produced originally by certain planktons and protozoans in the ocean. These same microorganisms are responsible for the “red” (blue, brown, white, black, and so on) tides that occur in warm summer months. The shellfish (such as California mussels, which are quarantined each year from May through October) dine on the microorganisms and concentrate the poison in their digestive organs and muscle tissues. Generally, crabs, shrimp, and abalone are safe to eat.

The victim of paralytic shellfish poisoning should be brought immediately to a hospital. If he is having trouble breathing, be prepared to assist him (see page 29).

Anisakiasis

If the worm(s) is not removed by a physician, who must do this physically through an endoscope passed through the esophagus into the stomach, it dies within a few days. However, implantation can initiate an abscess. Some worms don’t implant, but are coughed up, vomited up, or passed in the stool. If a worm crawls into the esophagus or throat, an unusual tingling feeling can develop.