Chapter 265 Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome

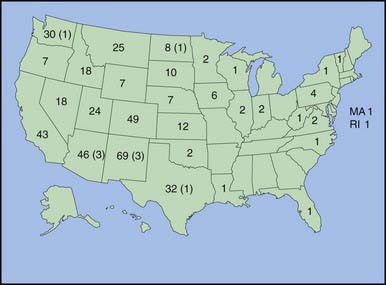

The Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) is caused by multiple closely related hantaviruses that have been identified from the western USA, with sporadic cases reported from the eastern USA (see ![]() Fig. 265-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com) and Canada and important foci of disease in several countries in South America. HPS is characterized by a febrile prodrome followed by the rapid onset of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema and hypotension or shock. Sporadic cases in the USA caused by related viruses may manifest with renal involvement. Cases in Argentina and Chile sometimes include severe gastrointestinal hemorrhaging; nosocomial transmission has been documented in this geographic region only.

Fig. 265-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com) and Canada and important foci of disease in several countries in South America. HPS is characterized by a febrile prodrome followed by the rapid onset of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema and hypotension or shock. Sporadic cases in the USA caused by related viruses may manifest with renal involvement. Cases in Argentina and Chile sometimes include severe gastrointestinal hemorrhaging; nosocomial transmission has been documented in this geographic region only.

Treatment

Management of patients with Hantavirus infection requires maintenance of adequate oxygenation and careful monitoring and support of cardiovascular function. The pathophysiology of HPS resembles that of dengue shock syndrome (Chapter 261). Pressor or inotropic agents, such as dobutamine, should be administered in combination with judicious volume replacement to treat symptomatic hypotension or shock while avoiding exacerbation of the pulmonary edema. Intravenous ribavirin, which is lifesaving if given early in the course of HFRS, has been shown to be of no value in HPS.

Armstrong LR, Bryan RT, Sarisky J, et al. Mild hantaviral disease caused by Sin Nombre virus in a four-year-old-child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;12:1108-1110.

Bryan RT, Doyle TJ, Moolenaar RL, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in children. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 1997;8:44-49.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: five states, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:627-628.

Childs JE, Ksiazek TG, Spiropoulou CF, et al. Serologic and genetic identification of Peromyscus maniculatus as the primary rodent reservoir for a new Hantavirus in the southwestern United States. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1271-1280.

Figueiredo LT, Moreli ML, de-Sousa RL, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, central plateau, southeastern and southern Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:561-567.

Godoy P, Marsac D, Stefas E, et al. Andes virus antigens are shed in urine of patients with acute Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome. J Virol. 2009;83:5046-5055.

Khan AS, Khabbaz RF, Armstrong LR, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: the first 100 U.S. cases. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1297-1303.

Pergam SA, Schmidt DW, Nofchissey RA, et al. Potential renal sequelae in survivors of Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:279-285.

Peters CJ, Khan AS. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: the new American hemorrhagic fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1224-1231.