Chapter 13. Hand injuries

The hand is a complex structure and even a slight disturbance in one part can have serious effects on its function as a whole. Because the hand is so important to work, leisure and everyday living, hand injuries demand special care and attention.

Hand injuries can involve:

• Nerves.

• Bones.

• Joints.

• Tendons.

• Skin and soft tissue.

• Blood vessels.

Nerves

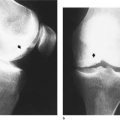

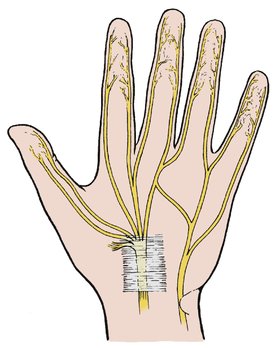

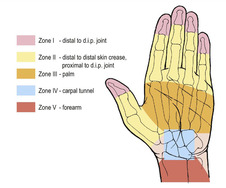

The different types of nerve lesion and their management are described on pages 109, 141 (Fig. 13.1).

|

| Fig. 13.1

Nerve supply to the palm of the hand. Note the position of the digital nerves and the median and ulnar nerves at the wrist, and the median nerve passing beneath the transverse carpal ligaments.

|

Median nerve

The median nerve may be cut cleanly across at the wrist or palm by sharp objects or by falls through windows.

Treatment

These injuries are ideal for immediate repair; i.e. within 24 h of injury. The results are generally good, particularly in children, but complete recovery never occurs. The flexor tendons are usually injured at the same time and accurate repair of all the structures involved can be very difficult.

Ulnar nerve

The ulnar nerve can also be damaged in this way but it lies deeper than the median nerve and is protected by the tendon of flexor carpi ulnaris.

Treatment

As with the median nerve, the results of repair are acceptable but never perfect.

Digital nerves

The palmar digital nerves are very vulnerable and are cut if the patient grips a blade or a sharp object. The digital artery is usually damaged at the same time. Because the volar digital nerve supplies the pulp of the finger, injuries to it can seriously impair function.

Treatment

The cutaneous nerves on the dorsum of the finger, distal to the middle of the middle phalanx, are too small to repair. On the palmar surface the nerve is large enough to repair as far distally as the distal interphalangeal joint. Lesions proximal to these points should be repaired under magnification.

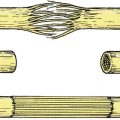

Crushed nerves and dirty wounds

Contaminated or untidy nerve lesions are not suitable for immediate repair.

Treatment

The ends of the nerve can be tagged with a marking suture and the nerve repaired when the wound has healed. The end of the nerve will then have a firm fibrous cap of epineurium, which must be removed before it can be repaired. The nerve must also be mobilized proximally and distally to give extra length.

Flexor tendons

Anatomy

The flexor tendons run part of their course through synovial and fibrous sheaths. The fibrous sheaths, which are lined with synovium, run from the distal interphalangeal (d.i.p.) joints to the distal palmar skin crease and prevent the tendon ‘bowstringing’ when the finger is flexed.

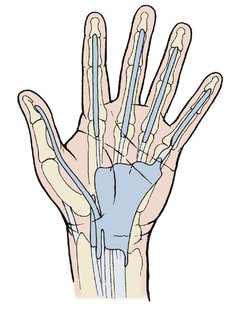

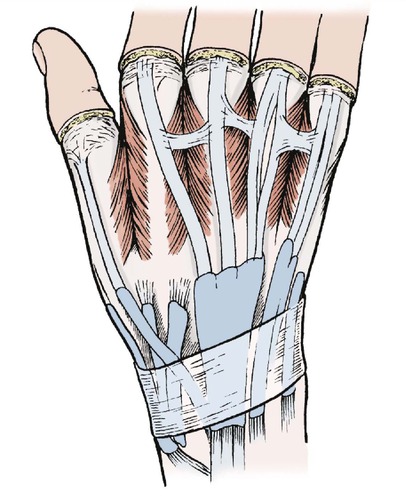

The synovial sheaths of the thumb and little fingers extend proximally through the carpal tunnel. The three central digits (index, middle and ring) have a separate flexor sheath in the fingers. There is also a sheath in the palm which extends proximal to the wrist (Fig. 13.2).

|

| Fig. 13.2

Tendon sheaths in the palm and wrist.

|

Sites of flexor tendon injury

Zone I: distal to d.i.p. joint.

Zone II: in the fingers.

Zone III: in the palm.

Zone IV: in the carpal tunnel.

Zone V: in the forearm.

Because of these complexities, flexor tendon injuries should be treated only by experienced surgeons.

Zone I: Lesions distal to the tendon sheath

Injuries distal to the d.i.p. joint lie outside the sheath.

Treatment

Zone I lesions can be treated by (1) tendon advancement, or (2) arthrodesis of the d.i.p. joint.

The cut end of the tendon can be advanced and reinserted on the distal phalanx. This may cause a slight flexion deformity.

In the thumb the advancement can be done in the forearm because the flexor pollicis longus has no connection with other flexors and its tendon can be separated from the muscle belly in the forearm and moved distally.

The results of surgery are better in the thumb than the fingers.

Early movement, active or passive, is important after any tendon repair and several devices are available to encourage this.

Zone II: Injuries in the fingers

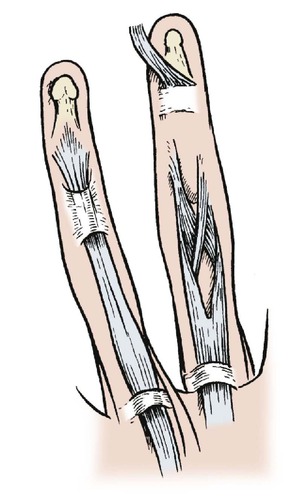

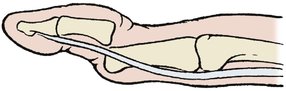

Management of flexor injuries in the fingers depends on the tendons involved and the site of injury (Fig. 13.3). The first step is to decide which tendon has been damaged.

|

| Fig. 13.3

Flexor tendon injuries to the hand.

|

Profundus and superficialis action can be distinguished by asking the patient to flex the distal phalanx with the middle phalanx held still (see Fig. 2.26). Only flexor profundus will do this because superficialis does not extend beyond the middle phalanx (Fig. 13.4).

|

| Fig. 13.4

The relationship of flexor digitorum profundus and superficialis.

|

To assess superficialis, hold all the fingers down except the one that is to be tested and ask the patient to flex that finger. If the finger flexes at the proximal interphalangeal (p.i.p.) joint, superficialis is intact. Test this on your own hand.

Treatment

Division of superficialis and profundus. If the tendons are cut opposite the proximal or middle phalanx they can be treated either by meticulous primary repair by an experienced surgeon or by replacing the tendon with an autograft of another tendon, such as palmaris longus or plantaris. If both tendons are cut, both should be repaired.

Division of profundus alone. If the tendon is divided within 1 cm of its insertion the tendon can be pulled up, or ‘advanced’, and the cut end attached to the distal phalanx.

Zone III: Injuries in the palm

Division of the flexor tendons in the palm is less serious than division in the fingers because the repair can be done outside the fibrous or synovial sheaths.

Treatment

The tendons should be repaired meticulously by an experienced hand surgeon and early mobilization instituted.

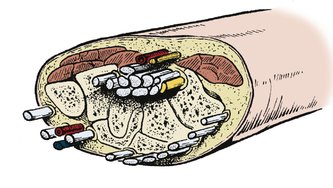

Zone IV: Injuries in the carpal tunnel

Eleven flexor tendons (flexor digitorum superficialis (4), flexor digitorum profundus (4), flexor pollicis longus, flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor carpi radialis) cross the volar aspect of the wrist (Fig. 13.5). If all these are divided, there will be 22 cut tendon ends. If the median nerve is divided as well, there will be 24 structures, which must be carefully identified, and if each pair is joined there will be 12 suture lines very close together. However carefully repaired, the tendons and nerves may stick together and form a solid mass which restricts movement at the wrist.

|

| Fig. 13.5

Structures crossing the wrist.

|

Treatment

The problem can be simplified by discarding those tendons that are not absolutely necessary. The flexor superficialis, for example, can be sacrificed if flexor profundus is working. Finger flexion will still be full and the risk of adhesions between superficialis and profundus outweigh the improvement of function that might be obtained by repairing both.

Zone V: Injuries in the forearm

Injuries in the forearm lie outside any sheath and can be accurately repaired more easily than elsewhere.

Treatment

The tendon ends are accurately identified and repaired, and early mobilization begun.

Contaminated wounds and crushing injuries

If the wound is untidy and dirty it must be debrided and all dead tissue removed. If the wound is untidy but clean it is sometimes better to excise the tendon and replace it with a Silastic rod, which can itself be replaced with a graft when the wound has healed.

If the wound is contaminated, a clean and well- healed wound must be obtained before definitive treatment is undertaken.

Aftercare

The hand should be mobilized actively and passively as soon as pain and swelling permit.

Extensor tendons

Anatomy

Because the extensor tendons only have a synovial sheath where they cross the wrist, the problems encountered in repairing flexor tendons in the fingers do not arise. The tendons are easily identified, repair is straightforward and the fingers can be mobilized after 3 or 4 weeks.

If the tendons are divided on the dorsum of the hand they cannot contract for more than a few millimetres because they are restricted by linking fibrous bands. Even without repair some extensor function will eventually return (Fig. 13.6).

|

| Fig. 13.6

Anatomy of the extensor tendons to show the tendon sheaths and extensor hoods.

|

Treatment

Tendons divided on the dorsum of the hand should be repaired and the fingers splinted in extension for 3 weeks.

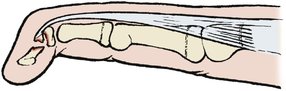

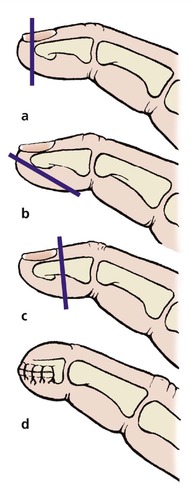

Mallet finger

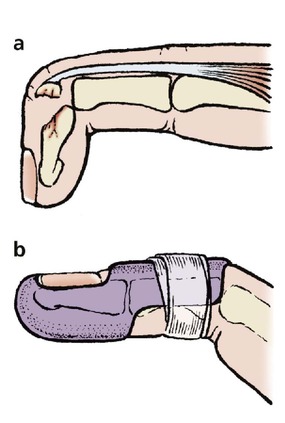

Violent flexion injuries to, or lacerations across the back of, the d.i.p. joint can avulse or divide the insertion of the extensor digitorum longus at the base of the distal phalanx (Fig. 13.7 and Fig. 13.8).

|

| Fig. 13.7

(a) A mallet finger with avulsion of the extensor tendon from the distal phalanx; (b) a mallet finger splint holding the d.i.p. joint extended.

|

|

| Fig. 13.8

Radiograph of a mallet finger.

|

Untreated, the lesion causes the distal phalanx to droop and leaves a ‘mallet’ finger deformity. The condition is inconvenient but function improves without treatment and it is exceptional for the patient to be seriously troubled by the injury 12 months later.

Treatment

Although the results are acceptable without treatment, splintage can produce a better result. The finger should be immobilized for 6 weeks in a mallet finger splint which holds the d.i.p. joint hyperextended but allows movement at the p.i.p. joint (Fig. 13.7b). Some loss of active extension may persist.

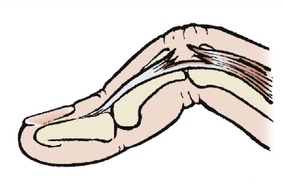

Boutonnière lesion

The central slip of the extensor expansion can be detached from its insertion at the base of the middle phalanx by a cut or by violent muscle contraction. This allows the two lateral slips to fall sideways and the p.i.p. joint to protrude between the two, which produces a characteristic deformity and may impair function (Fig. 13.9).

|

| Fig. 13.9

A boutonnière lesion of the p.i.p. joint.

|

Treatment

The lesion should be splinted with the finger straight, but the results are imperfect. If the final disability justifies it, the two slips can be approximated to restore extension but flexion may be lost.

Blood vessels

Injuries at the wrist

Damage to the radial or ulnar arteries at the wrist causes severe arterial bleeding, which can be controlled by firm pressure and elevation.

Treatment

If both radial and ulnar arteries are ligated, ischaemia of the hand may result, and at least one, preferably the radial, should remain intact. If both treatment arteries are damaged, arterial repair is required.

Note: Be very careful when applying artery forceps near the wrist: arteries, nerves and tendons can all be damaged very easily.

Injuries in the palm

The deep palmar arch can be cut by penetrating injuries and causes serious bleeding.

Treatment

Bleeding must be stopped to avoid a large palmar haematoma and skin necrosis.

Skin and subcutaneous tissue

Crushing injuries

Fingers can be crushed so hard that the skin bursts. These injuries must be treated by elevation of the arm and hand and the wounds must never be sutured. Although it is technically possible to close the wounds soon after injury, the sutures prevent the soft tissues from swelling and a stiff or dead digit will follow.

Treatment

The wound should be cleaned, lightly dressed and the hand elevated. After 48 h the swelling will begin to subside and the skin edges will come together on their own. Delayed primary suture is sometimes needed.

Degloving injuries

If the hand is caught in machinery, the skin of the hand and fingers can be peeled off like a glove (Fig. 13.10). This is a serious lesion and cannot be treated by rolling the skin back into place. The lesion can be caused by a ring.

|

| Fig. 13.10

Injury to the little finger caused by a ring. This type of injury can cause degloving. Note the small flap of skin at the p.i.p. joint.

|

Treatment

The skin defect must be grafted by an experienced surgeon, either by removing the subcutaneous fat from the degloved skin and applying it as a free graft or by taking a graft from elsewhere. If paratenon is stripped from the tendons, flap cover is required. Alternatively, the ring finger can be amputated and its skin used to cover the defect.

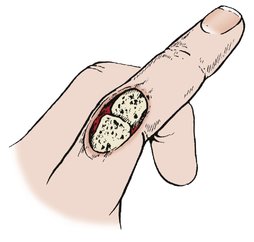

Grindstone injuries

Accidental contact with a grindstone removes skin, subcutaneous tissue and bone (Fig. 13.11). The wound is contaminated and the loss of tissue can be irreparable.

|

| Fig. 13.11

A grindstone injury of the hand with destruction of the extensor tendon and exposure of the joint surface.

|

Treatment

Treatment depends on the lesion but, if the knuckle is involved, arthrodesis or amputation may be preferable to a protracted series of reconstructive procedures.

Injection injuries

Although rare, the injuries caused by high pressure injection devices such as high pressure water nozzles, paint sprays and grease guns can cause serious problems. These implements can force grease or water through the skin and into the subcutaneous tissues without any opening in the skin itself. The irritation in the soft tissues can lead to tissue necrosis and the integrity of the skin is misleading.

Treatment

The hand must be explored and all extraneous material removed. If this is not done the ensuing inflammation, particularly if complicated by infection, may lead to amputation.

Skin

Skin incisions or lacerations that cross skin creases on the flexor aspect of joints may shorten when they heal and form a tight fibrous contracture that holds the joint flexed. While there is no choice in the position of a laceration, incisions used to repair tendons and nerves must not cross skin creases transversely.

Treatment

The wound should be carefully cleaned, but never use spirit to clean a wound on the hand. The spirit will damage exposed nerve tissue and cause an intense inflammatory response in the flexor tendon sheath that restricts flexor tendon movement. Aqueous solutions of chlorhexidine or cetrimide are preferable and the detergent action of these agents is an added advantage.

Once cleaned, the wound edges can be brought lightly together with fine sutures and the hand elevated until swelling has subsided.

Human bites

Genuine human bites are uncommon away from the rugby field but knuckles are often injured against teeth – a ‘fight bite’. Injuries caused in this way often fail to heal and become badly infected with a cocktail of exotic organisms.

Treatment

The wound should be cleaned, excised and enlarged, and left unsutured, and adequate antibiotics given.

Fractures and dislocations

The management of fractures in the hand, like the management of fractures elsewhere, follows the principle that stable fractures should be mobilized soon, whereas unstable fractures should be stabilized and then mobilized. Early mobilization is even more important in the hand than elsewhere.

Waist of the scaphoid

Mechanism

The carpal bones are arranged in two rows, proximal and distal. The scaphoid bridges the two rows and is exposed to stresses not encountered by the other carpal bones.

Violent hyperextension of the wrist will crack the waist of the scaphoid across its narrowest point and any force that hyperextends the wrist will do this. In days past, this was called a ‘chauffeur’s fracture’ because a common cause was the starting handle of a petrol engine being flung backwards if the engine backfired while the handle was held incorrectly.

Fracture of the waist of the scaphoid is a treacherous fracture for several reasons:

1. It is not easily seen on initial radiographs, even if several views are taken (Fig. 13.12).

|

| Fig. 13.12

(a), (b) Fracture of the waist of the scaphoid.

|

2. The fracture can go on to non-union, especially if it is not immobilized (Fig. 13.13).

|

| Fig. 13.13

Non-union of the scaphoid.

|

3. Because the blood supply to the proximal pole of the bone enters by the distal pole in most people, the proximal fragment can be devitalized, which leads to aseptic necrosis of the scaphoid and osteoarthritis of the wrist.

4. There are very few reliable clinical signs.

Physical signs

There is no deformity, crepitus or bruising around a fractured scaphoid. The only physical signs are tenderness in the anatomical snuff-box with swelling, weakness of pinch and pain on hyperextension. Even these signs are not always present.

Treatment

A cast should be applied to immobilize the joint above and the joints below the fracture, i.e. the wrist, carpometacarpal and first metacarpophalangeal joints, and retained for a minimum of 6 weeks. The cast must hold the thumb roughly opposite the ring finger and not in wide abduction because that interferes with function and displaces the fragments.

If the fracture is not united by 12 weeks, internal fixation and grafting should be considered.

Tubercle of the scaphoid

The scaphoid has a small bony tubercle which can be avulsed. Fracture of the tubercle of the scaphoid is benign but unfortunately far less common than a fracture through the waist.

Treatment

Immobilization of the scaphoid is advisable for pain relief.

Fractures of the triquetral

Violent hyperextension of the wrist can separate a flake of bone from the triquetral.

Treatment

The fracture is little more than a soft tissue injury and need not be immobilized.

Carpal dislocations

Injuries to the carpus cause serious problems and they are frequently missed in the accident department, which makes the consequences even more serious. Like scaphoid fractures, they have a deservedly treacherous reputation.

Many types of instability occur but the commonest are: (1) perilunate dislocation, (2) trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation and (3) other types of carpal instability.

Perilunate dislocation

Violent hyperextension pushes the carpus off the back of the radius but the lunate usually remains attached to the radius. The lesion is easily missed on a simple anteroposterior radiograph but is obvious on the lateral (Fig. 13.14). The median nerve may be damaged and the consequences of missing this lesion are serious.

|

| Fig. 13.14

A perilunate fracture dislocation of the carpus accompanied by fracture of the triquetral and the lower end of the radius.

|

Dislocation of the lunate is the same injury as perilunate dislocation except that, as the soft tissues pull the hand forwards from the hyperextension that causes the dislocation, the lunate is pushed forwards from its normal position so that it lies in front of the other carpal bones.

Treatment. The dislocation must be reduced accurately and held reduced for at least 4 weeks. Open reduction is sometimes needed.

Trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation

This dislocation is the same as a dislocation of the lunate except that the fracture line passes through the waist of the scaphoid, leaving the proximal pole of the scaphoid attached to the lunate. Many patterns of fracture exist, some involving the radius as well.

Treatment. The fracture must be reduced carefully; open operation may be needed to replace the lunate. If the scaphoid is fractured, the carpus must be stabilized by internal fixation.

Other carpal instabilities

Instability of the carpus without a fracture is extremely difficult to diagnose at the time of injury, but becomes apparent later when the patient experiences pain or weakness of the carpus under stress.

Metacarpal injuries

The fifth metacarpal is broken more often than the others. There are three types of fracture: (1) fractures of the neck, (2) oblique fractures, and (3) transverse comminuted fractures.

Fifth metacarpal neck fracture

The metacarpals are often broken by injuries to the head of the bones with the fingers flexed; i.e. punching with the fist. The fifth metacarpal is almost invariably broken in this way, whatever the patient’s account of events (Fig. 13.15).

|

| Fig. 13.15

Displaced fracture of the fifth metacarpal neck caused by punching.

|

Treatment. The fracture results in a flexion and rotational deformity. Only rotation need be corrected and this can be done by holding the little finger lightly against the ring finger with elastic strapping and encouraging early flexion.

The fracture may unite with the metacarpal head drooping slightly below the line of the other knuckles and with a slight extensor lag of the little finger, which recovers. Neither causes noticeable disability.

Oblique fractures of the fifth metacarpal

Oblique fractures of the shaft are caused by the little finger being held and twisted. A nasty rotational deformity may be present.

Treatment. Rotation must be corrected carefully and the position maintained by holding the little finger against the ring finger.

Comminuted transverse fractures of the fifth metacarpal

Sideways blows to the edge of the hand will fracture the fifth metacarpal near its centre. This injury is often caused by crushing injuries to the hand, or karate practice, and leads to severe swelling of the hand, with an abduction deformity of the finger.

Treatment. The fracture should be reduced and the little finger held to the ring finger. A small plaster slab can be applied to the side of the hand to protect the fracture site from further trauma.

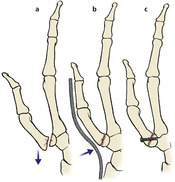

First metacarpal – Bennett’s fracture

The first metacarpal can be broken with the fracture line extending into the carpometacarpal joint to produce a Bennett’s fracture, which is often the result of punching (Fig. 13.16). If a boxer ‘sprains’ his thumb, he probably has a Bennett’s fracture. The fracture is unstable for three reasons:

1. The proximal fragment consists of a small triangular segment attached to the trapezium.

2. The fracture line is oblique.

3. The distal fragment has many strong muscles attached to it and these pull the thumb proximally.

|

| Fig. 13.16

Treatment of Bennett’s fracture. The fracture is unstable because of unopposed muscle action (a); it can be held by cast pressure (b) or screw fixation (c).

|

Treatment. If left untreated, malunion is inevitable, but the functional result is not always bad.

The fracture should be reduced and, if necessary, held with a percutaneous pin or screw (Fig. 13.16).

First metacarpal – transverse fracture

Transverse fractures produce malalignment of the shaft (Fig. 13.17 and Fig. 13.18).

|

| Fig. 13.17

Transverse fracture of the first metacarpal.

|

|

| Fig. 13.18

Transverse fracture of the first metacarpal at its base. This is not a Bennett’s fracture.

|

Treatment. Unless the fragments are impacted, the fracture should be reduced and held in a scaphoid cast.

Multiple metarcarpal fractures

Multiple metarcarpal fractures are caused by twisting and crushing injuries.

If more than one metacarpal is broken and the fragments are displaced, the alignment of the metacarpals must be restored with Kirschner wires passed through the intact metacarpals or a small bone plate. If this is not done, the distortion of the metacarpal arch can seriously interfere with finger function.

Metacarpophalangeal dislocations

The metacarpophalangeal joints can be dislocated by hyperextension and rotational strains. The injury is uncommon.

Treatment. Radiologically, these dislocations look deceptively easy to reduce but the metacarpal head sometimes ‘buttonholes’ through the volar tissues and becomes irreducible. Open reduction is then required.

Gamekeeper’s (poacher’s) thumb

The medial collateral ligament of the first metacarpophalangeal joint is easily torn by any violent abduction injury. The lesion is called a gamekeeper’s or poacher’s thumb because of the method used to break the neck of game, particularly rabbits. This story is not entirely accurate. Those who break animals’ necks in this way stretch their own ligaments gradually rather than break them suddenly (Fig. 13.19).

|

| Fig. 13.19

Poacher’s (or gamekeeper’s) thumb. The medial collateral ligament of the first metacarpophalangeal joint is torn.

|

The lesion is also caused by falls, particularly on dry ski slopes, where the hand may slide down the surface until the thumb catches on an irregularity or in a pole strap. The ligament can be either torn directly across or avulsed with a flake of bone.

Treatment. Left untreated the thumb is unstable and cannot resist the force on the index finger in a pinch grip. Cast immobilization or surgical repair of the lesion is often required but there may be some residual disability.

Phalanges

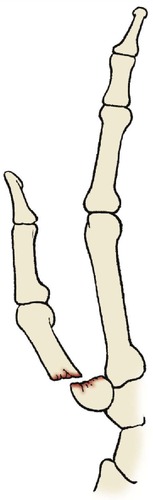

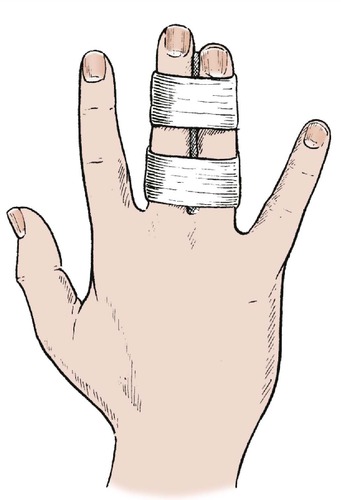

The phalanges are fractured most often by twisting or angular forces (Fig. 13.20). Angulation is easily corrected but rotational deformities from spiral fractures are more difficult.

|

| Fig. 13.20

(a) Spiral fracture of the proximal phalanx of the little finger; (b) satisfactory position achieved by strapping the little finger to the adjacent ring finger.

|

The bone usually unites soundly, the most urgent problem being the preservation of normal movement between tendon and bone.

Treatment. The simplest and most effective treatment for stable phalangeal fractures is to hold the damaged finger against its neighbour and encourage flexion, which is impossible if there is a rotational deformity (Fig. 13.21).

|

| Fig. 13.21

Strapping adjacent fingers.

|

The fingers should be held lightly together with elastic strapping to allow room for the swelling that is bound to follow a fracture, and a small layer of felt or other absorbable material placed between the two fingers to absorb sweat and avoid skin irritation.

Unstable fractures sometimes need internal fixation (Fig. 13.22).

|

| Fig. 13.22

(a) An unstable fracture of the proximal phalanx, treated by internal fixation (b), (c).

|

Juxta-epiphyseal fracture separations

The phalanges are ‘long bones’ and can sustain fracture separations of the epiphysis just like those of the femur and tibia (Fig. 13.23).

|

| Fig. 13.23

Juxta-epiphyseal fracture separation of the distal phalanx.

|

Treatment. The fracture should be reduced and early mobilization commenced. Residual deformity will be corrected well by remodelling.

Interphalangeal fracture dislocations

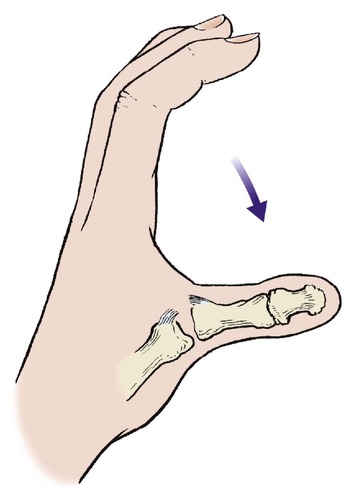

Violent hyperextension of the thumb or fingers can avulse a fragment of the middle phalanx which remains attached to the proximal phalanx by the volar plate (Fig. 13.24). This is not a straightforward injury and may lead to a very stiff digit from scarring and fibrosis around the front of the interphalangeal joint.

|

| Fig. 13.24

Intra-articular fracture of the p.i.p. joint with avulsed volar plate.

|

Treatment. If the avulsed fragment includes more than one-third of the articular surface, the fracture will be unstable and fixation with a pin may be needed. If the fragment involves less than one-third of the articular surface, the finger should be immobilized in flexion.

Phalangeal dislocation

The interphalangeal joints of the thumb and fingers dislocate and reduce easily. The dislocation may have reduced spontaneously, or have been reduced by longitudinal traction, before the patient reaches hospital.

Some swelling is inevitable around every dislocation but there is so little subcutaneous fat around the interphalangeal joints that any additional soft tissue is easily visible. For this reason, patients should be advised that the swelling of a dislocated finger will continue to subside for as long as 2 years after the injury but will never subside completely. Any rings worn on the affected finger which do not fit at the end of this time will need to be enlarged.

Treatment. Rigid immobilization is not required but the finger should be held loosely against its neighbour and early mobilization begun. The strapping can be removed after approximately 2 weeks.

Reduction is not always easy. If the head of the phalanx slips through a defect in the capsule, reduction is impossible and open reduction will be needed, as for metacarpophalangeal dislocations (Fig. 13.25).

|

| Fig. 13.25

Dislocation of the p.i.p. joint with dislocation of the head of the proximal phalanx between the superficialis tendons.

|

Intra-articular fractures

The phalanges can break through their condyles to produce a very unstable intra-articular fracture.

Treatment. Like unstable fractures anywhere else, accurate reduction is important. Fixation with a percutaneous wire may be needed.

Amputations

Fingertips

Amputation of the fingertip is a regrettably common industrial accident, although guards on machines in sawmills and sheet metal works have reduced the incidence considerably.

The aim of treatment should be a mobile finger with innervated skin and a useful tip. If the fingertip lacks sensibility or, worse, is exquisitely tender, it will not be used and it is far better to take more off the finger if this will leave a better stump. For this reason, it is not always helpful to reattach amputated fingers, however cleanly they may have been amputated.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the level of amputation, of which there are three (Fig. 13.26).

|

| Fig. 13.26

Fingertip amputations: (a) amputation through the nail; (b) amputation through the pulp; (c) amputation through the nail and distal phalanx. (d) A skin flap brought up to cover the end of the amputated phalanx.

|

Vertical through the nail. These are treated by a local flap of skin to cover the defect, or by a split skin graft. The defect becomes smaller as the graft contracts to leave a small scar protected by the nail. A split skin graft is easier to apply but the result is not as good as that which follows a successful whole thickness local flap.

Oblique through the pulp. These are closed with a local flap or full thickness graft.

Vertical through the nail and distal phalanx. These are treated by nibbling the end of the phalanx and primary closure, bringing sensitive pulp skin over the tip.

Fingers

Many amputations are clean transverse cuts made with a clean blade. Others are contaminated crushing injuries.

Treatment

Management is directed to producing the most useful stump possible, which may mean shortening it further. It is better to have a finger that ends in the proximal half of the phalanx rather than at an interphalangeal joint and, whenever possible, to leave the flexor and extensor tendon insertions intact.

Sensibility is important. A flap of healthy and innervated skin from the volar aspect can be used to cover the fingertip. If this is not possible, a graft can be stitched over the cut end of the finger to achieve primary closure. If the resulting function is unsatisfactory, the stump can be shortened later.

In some patients, a neuroma forms on the cut end of the digital nerve and produces an exquisitely tender spot that prevents the patient using the finger at all. A protective finger-stall or glove may be helpful but resection of the digital nerve may be needed to place the end of the nerve in a less vulnerable position. Percussion of the neuroma is painful and ineffective but is still recommended in some centres.

Crushing amputations are treated by debridement, elevation and definitive amputation when the swelling has subsided.

Thumb

Traumatic amputation of the thumb is a serious and disabling injury – worse than losing several fingers. If you do not believe this, tuck your thumb into the palm and see how much you can do with just the fingers.

Treatment

Only the thumb can be opposed to the other fingers. If lost, it may be necessary to create a new one by ‘pollicizing’ the index finger. Even if the resulting ‘thumb’ is insensitive and stiff, it can still serve as an opposition post for the other digits.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation of the hand involves:

• Bones.

• Tendons.

• Joints.

• The whole patient!

Bones

The hand depends for its function upon the movement of its constituent parts over each other. Most fracture management is centred upon encouraging bones to unite soundly in the correct position, even if this means immobilizing soft tissues, but the aim in treating fractures of the hand is to keep the soft tissues moving while the fracture is uniting.

Tendons

Each finger has seven tendons (extensor digitorum, two interossei and one lumbrical, two slips of flexor digitorum superficialis and one flexor digitorum longus). If any of these tendons stick to bone or to another tendon, movement of the finger will be restricted.

Joints

Interphalangeal joints

Joint stiffness is a special problem. The interphalangeal joints become stiff if immobilized in flexion because the volar plate sticks to the front of the phalanx.

Once stuck, the volar plate cannot be mobilized, the collateral ligaments contract and the fingers will never straighten again. The fingers must therefore be immobilized in full extension.

Metacarpophalangeal joints

The metacarpophalangeal joints become stiff in extension because the capsule and collateral ligament are lax in this position and contract.

The metacarpophalangeal joint must therefore be immobilized in flexion to keep the collateral ligaments and the capsule stretched.

Position for splinting

If the hand is immobilized with the metacarpophalangeal joints flexed and the fingers straight (Fig. 13.27) the joints can be made to move again, but if immobilized in the opposite position they will become stiff and normal movement will not return.

|

| Fig. 13.27

Position for splinting the hand with the metacarpophalangeal joints flexed and the interphalangeal joints extended.

|

In any hand injury it is important to maintain mobility of the fingers and minimize swelling. If there is abnormal swelling of the hand, the patient should be admitted to hospital and the arm elevated before definitive treatment is begun.

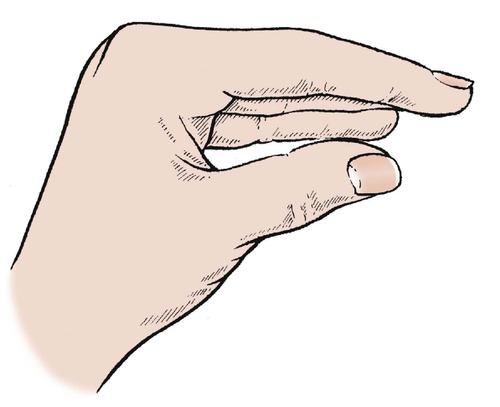

Functions of the hand

The hand can hold things in many ways and it is useful to consider the different grips when reconstructing an injured hand (Fig. 13.28).

|

| Fig. 13.28

Different functions of the hand: (a) power grip; (b) hook grip; (c) pinch grip; (d) key grip; (e) precision pinch; (f) chuck grip.

|

Power grip

The power grip is used for holding hammers, tennis racquets and golf clubs. A full range of flexion of the fingers is essential. The little, ring and middle fingers are more important than the thumb and index, which are used primarily for precision work.

In right-handed patients, the power grip in the left hand may be more important than the right because it is the left hand that holds the objects being worked upon by the right hand.

Hook grip

The curled fingers can be used as a hook for carrying baskets and swinging from branches. This is one of the few functions still possible if the metacarpophalangeal joints become stiff in extension.

Precision grips

Pinch grip

A pinch grip between the pulps of the thumb and index finger is essential for fine work. If the index is lost, the middle or ring finger can be used almost as well. In some circumstances, the pinch between the middle finger and thumb is so much better than that between the thumb and a stiff insensitive index that the index actually gets in the way and has to be amputated to improve the function of the hand.

Precision pinch

For extra precision the tips of the thumb and index are opposed to meet end to end, reducing the contact area to a minimum. Full flexion of the interphalangeal joints is needed for this function.

Key grip

A pinch grip between the thumb and the side of the flexed index is useful for holding keys and is also useful if the end of the index is lost.

Chuck grip

The fingers of the hand can be used like a drill chuck, grasping an object on all sides.

Other functions

Paperweight

Insensitive hands without motor control are useful as paperweights but little else. Nevertheless, this function is valued by patients to hold down objects being worked upon with the other hand.

Combined functions

These basic functions can be combined or modified for other purposes, e.g. holding a pen or a knife, but the basic concept of giving the patient a power grip to hold objects firmly, and a pinch grip for fine work, should be considered when planning treatment.