Hair Disorders

Joseph M. Lam, Li-Chuen Wong

Introduction

This chapter covers neonatal hair patterns, genetic hair shaft abnormalities, and the conditions in which hypo- or hypertrichosis are present in the neonatal period. There are many syndromes in which hypotrichosis or atrichia occur, and those in which it is a prominent feature are discussed. Localized alopecia can occur physiologically, with trauma, and as a nevoid disorder, either alone or associated with other nevi. Diffuse hypertrichosis can occur alone or as part of various syndromes. Localized hypertrichosis may occur with other nevi, but also may be a marker for serious neural tube closure defects (see also Chapter 9).

Neonatal hair development

The hair root is characterized by three definable stages of growth: anagen, catagen, and telogen.

The anagen stage is a growth phase that may last for many years. The catagen stage is a brief transition from the growth phase (anagen) to an inactive state. The telogen stage is the resting phase following catagen and lasts approximately 3 months. In adults, each region of the scalp contains hairs in different phases of the hair cycle.

In the fetus, hair follicles appear at about 10 weeks’ gestation and by 20 weeks’ gestation, all the hair on the scalp is in anagen phase. At about 30 weeks’ gestation, the hair in the frontal and parietal region rapidly transition through a catagen and telogen phase, representing the first shedding for the fetus. At or just before birth, scalp hair grows in synchronized waves, starting with the hairs in the frontal and parietal regions and ending with the occipital region. Hair density, structure, and growth vary depending on sex, ethnicity and nutritional status. From the 18th week after birth, changes in growth patterns progressively adopt the dyssynchronous pattern of the adult scalp.1–3

Scalp hair whorls

The sloping angle of scalp hair results from stretch on the scalp from the growth of the underlying fetal brain during weeks 10–16 of gestation. The usual location of the parietal hair whorl is several centimeters anterior to the posterior fontanelle. Of normal Caucasian infants, 95–98% have a single hair whorl in the parietal area,4,5 usually clockwise but inconsistent in position. The remainder have a double parietal whorl. Only 10% of African-American individuals with short curly hair have a parietal whorl.5 A mild frontal upsweep or ‘cowlick’ is present in 7% of normal infants.4 Hair patterns may be very abnormal in infants with structural abnormalities of the brain, demonstrating a striking frontal upsweep and absent or aberrant parietal whorls.4 Multiple parietal whorls occur with increased frequency in developmentally delayed children, and their presence in the neonate may be an early sign of such a disorder.6 A recent study of hair whorl orientation and handedness suggests that a single gene controls these traits.7

The hairline

The frontal hairline of neonates is lower than in older children, a feature most striking in racial groups in which there is profuse hair at birth. These terminal hairs on the brow are gradually replaced over the first 12 months of life by vellus hairs. Normally, posterior hairline hair roots are located above the neck crease. Low frontal and posterior hairlines are each associated with several syndromes, summarized in Box 31.1.

Heterochromia of scalp hair

Heterochromia of the hair is described as the growth of hair with two distinct colors in the same person.8 In piebaldism, there is a white forelock, which will be obvious in a dark-haired neonate. A congenital melanocytic nevus may present as a tuft of dark hair, which is often also longer and coarser than the surrounding normal hair. In hereditary, usually autosomal dominant, heterochromia, there may be a tuft of red hair in a dark-haired neonate or a dark tuft in a fair individual. There has recently been a report of a diffuse heterochromia of scalp hair, present from birth, with black and red hairs evenly distributed over the scalp8 and heterochromia of the scalp hair following Blaschko’s lines.9

Hair shaft abnormalities

A diverse group of conditions can result in hair shaft abnormalities. Some are associated with extracutaneous disease, whereas others affect only the hair itself. These conditions have been reviewed in detail by Whiting,10 Price,11 and Rogers.12,13

Trichoscopy performed with a handheld dermoscope or a video-dermoscope is becoming a useful tool in the diagnosis of hair shaft disorders.14

Monilethrix

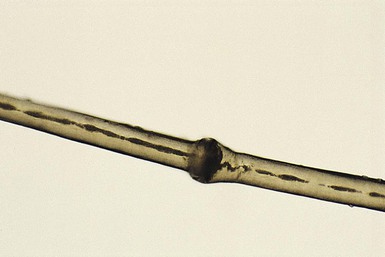

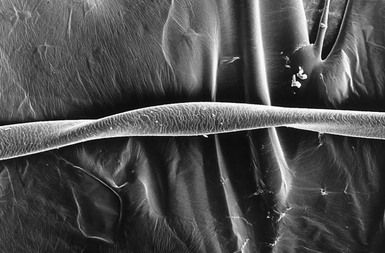

Monilethrix is a condition that produces a beaded appearance of the hair and the term comes from the Latin word for necklace (monile) and the Greek for hair (thrix).10–12 Most families with monilethrix show an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, but autosomal recessive forms also exist. The hair is usually normal at birth but is replaced within weeks by affected hairs that are dry, dull, and brittle, breaking spontaneously and leaving a stubble-like appearance (Fig. 31.1). The hairs may break almost flush with the scalp or may attain lengths of 0.5–2.5 cm, or occasionally longer. There may be spontaneous improvement with time, especially during puberty and pregnancy, but the condition never resolves completely. Follicular keratosis is commonly associated and may involve the scalp, face, and limbs. On microscopy, spindle-shaped ‘nodes’ separated by constricted internodes are seen (Fig. 31.2![]() ). The nodes have the diameter of normal hair and may be medullated, whereas the internodes are narrower and usually nonmedullated, and are the sites of fracture. In monilethrix the hair shaft fragility is due to structural weakness of the hair fiber that is caused by a genetic defect in keratin intermediate filament protein. Mutations in the hair cortex keratin genes KRT81 (hHB1), KRT83 (hHB3), and KRT86 (hHB6) have been identified in autosomal dominant monilethrix.15 An autosomal recessive form of monilethrix is caused by mutation in the DSG4 gene and presents with more extensive alopecia of the scalp, body, and limbs, and a papular rash involving the extremities and periumbilical region.16

). The nodes have the diameter of normal hair and may be medullated, whereas the internodes are narrower and usually nonmedullated, and are the sites of fracture. In monilethrix the hair shaft fragility is due to structural weakness of the hair fiber that is caused by a genetic defect in keratin intermediate filament protein. Mutations in the hair cortex keratin genes KRT81 (hHB1), KRT83 (hHB3), and KRT86 (hHB6) have been identified in autosomal dominant monilethrix.15 An autosomal recessive form of monilethrix is caused by mutation in the DSG4 gene and presents with more extensive alopecia of the scalp, body, and limbs, and a papular rash involving the extremities and periumbilical region.16

Pili torti

This is characterized by groups of three or four regularly spaced twists of the hair shaft on its own axis (Fig. 31.3![]() ).9,10 Microscopically, twists are seen, each 0.4–0.9 mm in width, occurring usually in groups of three or more at irregular intervals. Twists are almost always 180°, although some are 90° or 360°. The hair shaft is somewhat flattened. Pili torti may occur as an isolated phenomenon, with onset at birth or in the early months of life. The hair is usually fairer than expected and is spangled, dry, and brittle, breaking at different lengths (Fig. 31.4). It may stand out from the scalp and tends to be short, especially in areas subject to trauma.

).9,10 Microscopically, twists are seen, each 0.4–0.9 mm in width, occurring usually in groups of three or more at irregular intervals. Twists are almost always 180°, although some are 90° or 360°. The hair shaft is somewhat flattened. Pili torti may occur as an isolated phenomenon, with onset at birth or in the early months of life. The hair is usually fairer than expected and is spangled, dry, and brittle, breaking at different lengths (Fig. 31.4). It may stand out from the scalp and tends to be short, especially in areas subject to trauma.

Pili torti can occur alone or as a manifestation of defined syndromes, some of which are identifiable in the neonatal period. Menkes syndrome is an X-linked recessive condition caused by mutations in a gene encoding for a protein believed to be a copper-transporting P-type ATP-ase,17 and the multiple abnormalities are due to decreased bioavailability of copper, with resultant functional deficiencies of copper-dependent enzymes. In the early months of life, scalp and eyebrow hair becomes kinky, coarse, and sparse. Lax, pale skin, hypotonia, and early neurodegenerative changes may already be seen in the neonatal period. In Bazex syndrome, inherited as an X-linked dominant trait,18 congenital hypotrichosis with pili torti is associated with follicular atrophoderma and multiple facial milia, both of which may also be present from birth. These patients have an increased susceptibility to the development of basal cell carcinomas. In Björnstad syndrome, pili torti is associated with sensorineural deafness and occasionally mental retardation.19 In later childhood, normal hair may replace the affected hairs, with a considerable improvement in appearance. Both autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance patterns have been reported. Recently the gene for Björnstad syndrome has been mapped to chromosome 2 in a family with an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance (Fig. 31.5![]() ).19 Pili torti may occur also in Rapp–Hodgkin syndrome, although pili canaliculi is the more characteristic finding.

).19 Pili torti may occur also in Rapp–Hodgkin syndrome, although pili canaliculi is the more characteristic finding.

Trichorrhexis nodosa

The term trichorrhexis nodosa (TN) refers to the light microscopic appearance of a fracture with splaying out and release of individual cortical cells from the main body of the hair shaft, producing an appearance suggestive of the ends of two brushes pushed together (Fig. 31.6![]() ).10–12 When the break occurs, the brush-like end is clearly seen. Electron microscopy shows the disrupted cuticle and splaying of cortical cells. The defect renders the hair very fragile, and it breaks readily with trauma – or sometimes probably spontaneously. In congenital autosomal dominant TN, the hair is usually normal at birth but is replaced within a few months with abnormal, fragile hair. Trichorrhexis nodosa was found in eight of 25 children with mitochondrial disorders in the absence of skin manifestations, suggesting that hair examination may be a useful diagnostic tool when these disorders are suspected.20 Trichorrhexis nodosa is also seen in trichohepatoenteric syndrome, a condition that includes intractable diarrhea of infancy, facial dysmorphism, developmental delay, and immunodepression.21

).10–12 When the break occurs, the brush-like end is clearly seen. Electron microscopy shows the disrupted cuticle and splaying of cortical cells. The defect renders the hair very fragile, and it breaks readily with trauma – or sometimes probably spontaneously. In congenital autosomal dominant TN, the hair is usually normal at birth but is replaced within a few months with abnormal, fragile hair. Trichorrhexis nodosa was found in eight of 25 children with mitochondrial disorders in the absence of skin manifestations, suggesting that hair examination may be a useful diagnostic tool when these disorders are suspected.20 Trichorrhexis nodosa is also seen in trichohepatoenteric syndrome, a condition that includes intractable diarrhea of infancy, facial dysmorphism, developmental delay, and immunodepression.21

There is a growing list of conditions associated with trichorrhexis nodosa (Box 31.2).

Trichothiodystrophy

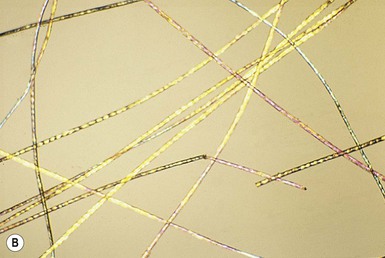

The term ‘trichothiodystrophy’ refers to the sulfur-deficient brittle hair that is a marker for a neuroectodermal symptom complex occurring in a group of autosomal recessive genetic disorders.22 There is considerable genetic heterogeneity in trichothiodystrophy.23 Named syndromes that fit into this spectrum include: Tay, Pollitt, Sabinas brittle hair, and Marinesco–Sjögren syndromes. The major clinical features seen in this group of conditions are photosensitivity with a DNA repair defect (due to mutations in the XPD ECCR2 DNA repair/transcription gene), ichthyosis, brittle hair, intellectual impairment, decreased fertility, short stature,24–26 and osteosclerosis. Some authors use mnemonic acronyms including PIBIDS, IBIDS, and BIDS to identify patients by these key clinical characteristics (see also Chapter 19).23 Features that may be evident in the neonatal period are intrauterine growth retardation, severe infections, congenital cataracts, nail dystrophy, facial dysmorphism, a collodion baby phenotype, and the characteristic fragile, dull, short, disordered hair involving the scalp hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes (Fig. 31.7).27,28 On light microscopy the hair has a wavy, irregular outline and a flattened shaft, in which twists like a folded ribbon occur. Two types of fracture are seen: an atypical trichorrhexis nodosa and trichoschisis, a clean, transverse fracture (Fig. 31.8A![]() ). Using crossed polarizers, light and dark bands are seen when the hair is aligned in one of the polarizer directions – the so-called tiger-tail appearance (Fig. 31.8B

). Using crossed polarizers, light and dark bands are seen when the hair is aligned in one of the polarizer directions – the so-called tiger-tail appearance (Fig. 31.8B![]() ). This may be absent at birth and is not fully developed until 3 months of age.29 Scanning electron microscopy shows irregular ridging and fluting and a disordered, reduced, or absent cuticle scale pattern.

). This may be absent at birth and is not fully developed until 3 months of age.29 Scanning electron microscopy shows irregular ridging and fluting and a disordered, reduced, or absent cuticle scale pattern.

Woolly hair

Woolly hair (WH) is an abnormal variant of tightly curled hair. Compared with normal curly hair, WH does not grow well and stops growing at a few inches.

Several families have been reported in which some affected individuals exhibit features of hypotrichosis while others have woolly scalp hair.30

Clinically, WH can be divided into syndromic and non-syndromic forms. The syndromic form includes Naxos disease, cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome and Carvajal syndrome.

Naxos disease is an autosomal recessive disorder that combines palmoplantar keratoderma and other ectodermal features with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. It was first reported in families on the Greek island of Naxos and is associated with a deletion in the plakoglobin gene. Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is characterized by a distinctive facial appearance, heart defects, and mental retardation and is caused by heterozygous gain-of-function mutations in one of four different genes: KRAS, BRAF, MEK1, or MEK2. Some patients have associated woolly hair. In Carvajal syndrome, patients present with epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma, woolly hair, and dilated cardiomyopathy. Carvajal syndrome can be caused by mutations in the gene encoding desmoplakin.31–36

Non-syndromic forms of hereditary woolly hair present as autosomal dominant (ADWH) or autosomal recessive (ARWH). Dominant forms of WH have been linked to mutations in the helix initiation motif of KRT74. Recessive forms of WH have been linked to mutations in the LIPH and the LPAR6/P2RY5 genes, both expressed in the inner root sheath of the hair follicle.

Localized and sporadic woolly hair (the woolly hair nevus) (Fig. 31.9) can also occur.

Uncombable hair

Uncombable hair is a relatively rare anomaly of the hair shaft that results in a disorganized, unruly hair pattern that is impossible to comb flat.11,13,37 Synonyms are spun-glass hair, pili canaliculi, and pili trianguli et canaliculi. In the classic clinical form, the hair is a light silvery-blond, paler than expected. It is frizzy, stands away from the scalp, and cannot be combed flat. It is often ‘spangled’ or glistening (Fig. 31.10). It is usually normal in length, quantity, and tensile strength. The onset may be with the first terminal growth or later. Eyebrows, lashes, and body hair are normal. Most cases improve with the onset of puberty. There are reports suggesting both dominant and recessive inheritance patterns. Scanning electron microscopy best demonstrates the characteristic shallow grooving or flattening of the surface.37 These areas are often discontinuous and change orientation many times along the length of the hair, occurring on different planes of the hair at different points. Cross-sectional microscopy shows triangular, reniform, and other unusual shapes. Most children with uncombable hair are otherwise normal; the findings have been demonstrated in a variety of other syndromes with congenital onset, including progeria, Marie Unna hypotrichosis,38 Rapp–Hodgkin syndrome,39 orofacial digital syndrome type I,40 ectrodactyly ectodermal dysplasia and clefting syndrome,40 and hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.39 The classic clinical appearance of spun-glass or uncombable hair would seem to depend on the proportion of abnormal hairs.

Pili annulati

This hair shaft abnormality, which may be present at birth, does not result in significant hair fragility. The hair looks pleasantly shiny, and on close observation alternating bright and dark bands are seen.41 There are usually no associated abnormalities. The condition may be sporadic or inherited, usually as a dominant characteristic. The bright areas are due to light scattered from clusters of air-filled cavities within the cortex, and in a hair mount, viewed with transmitted light, the light areas appear as dark patches. Scanning electron microscopy shows longitudinal wrinkling and folding in bands corresponding to the abnormal areas, possibly due to the evaporation of air in the spaces when the hair is coated in the vacuum. Transmission electron microscopy demonstrates multiple holes within the cortex. Recently, a locus for pili annulati was mapped to Ch12q24.32–24.33.42

Trichorrhexis invaginata

This is the characteristic hair shaft abnormality of Netherton syndrome, an autosomal recessive condition due to mutations in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes for the serine protease inhibitor LEKTI (see also Chapter 19).43 Although the severity varies considerably, the clinical and microscopic findings are present from birth. In the severely affected neonate, the hair may be extremely sparse or even absent altogether (Fig. 31.11). What hair is present is short and dull and breaks easily. The changes may affect eyebrows, eyelashes, and general body hair.13

Hair mount demonstrates a ball-and-socket configuration with various patterns seen (Fig. 31.12![]() ). The classic ‘bamboo hair’ occurs when the soft abnormal hair shaft wraps around a firmer distal shaft, producing the appearance of a shallow invagination of the distal into the proximal shaft. There is a tulip-like form with a deeper invagination and longer sides of the ‘cup.’11 Circumferential strictures may be found, representing the earliest stage of the invagination. The term ‘golf-tee hair’ has been given to the expanded proximal end of an invaginate node after a break has occurred. Thin vellus hairs may show multiple invaginations, the so-called ‘canestick hairs.’44 A helical pattern of twisting with obliquely running parallel invaginations has recently been described.45

). The classic ‘bamboo hair’ occurs when the soft abnormal hair shaft wraps around a firmer distal shaft, producing the appearance of a shallow invagination of the distal into the proximal shaft. There is a tulip-like form with a deeper invagination and longer sides of the ‘cup.’11 Circumferential strictures may be found, representing the earliest stage of the invagination. The term ‘golf-tee hair’ has been given to the expanded proximal end of an invaginate node after a break has occurred. Thin vellus hairs may show multiple invaginations, the so-called ‘canestick hairs.’44 A helical pattern of twisting with obliquely running parallel invaginations has recently been described.45

Diffuse alopecia (hypotrichosis)(Box 31.3)

Hypotrichosis with hair shaft abnormalities

As discussed in the previous section, many hair shaft abnormalities present in the neonatal period or in early infancy with significant hypotrichosis.

Isolated congenital alopecia or hypotrichosis without other defects

There appear to be several distinct genotypes within this group, with recessive, dominant, and X-linked inheritance patterns being represented.46,47

Those with recessive inheritance are in general the most severe and congenital in onset. In some pedigrees, there is a total absence of hair (congenital atrichia, atrichia congenita, alopecia universalis congenita) and on biopsy no hair follicles are found. Mutations in the hairless gene on chromosome 8 have been demonstrated in some families.46

In some dominant pedigrees, the hair is present but extremely sparse (congenital hypotrichosis, hypotrichosis simplex), with biopsy demonstrating a few scattered, miniaturized follicles occurring in decreased numbers; only the scalp is involved, the hair elsewhere being normal. In some of these pedigrees mutations have been found in corneodesmosin, a keratinocyte adhesion molecule.48

Marie-unna hypotrichosis

The hair in this autosomal dominant condition is usually sparse or absent at birth, but it is not until early childhood that the characteristic coarse, wiry hair appears, showing flattening and irregularly distributed twisting on microscopy.49,50 The condition has been mapped to a mutation in the inhibitory upstream open reading frame of the hairless gene on chromosome 8p21.51,52

Atrichia with papular lesions

This is a distinctive association of congenital atrichia and tiny, white papules.53 Atrichia of the scalp may be present from birth or appear in early childhood. In most cases, fetal hair is shed in the first 3 months of life and never replaced; eyebrows and eyelashes may or may not be involved (Fig. 31.13). The papular lesions, which occur diffusely but predominate on the face and scalp, are not present in the neonatal period. Histopathology shows the papules to represent keratin-filled follicular cysts in contact with the overlying epidermis. Recent work has demonstrated mutations in the hairless gene on chromosome 8, as seen also in alopecia universalis congenita.47

Vitamin D-dependent rickets type 2A (VDDR2A) can present with alopecia that is clinically and pathologically indistinguishable from that seen in atrichia with papular lesions.54

Congenital hypotrichosis and milia

In this condition, which bears some clinical similarity to atrichia with papular lesions, there is hypotrichosis with sparse, coarse hair, and multiple milia are present at birth on the face and sometimes also the limbs and trunk. Study of a large pedigree suggests X-linked dominant inheritance.55

Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy

Hair that is short and sparse from birth is a feature of this rare autosomal recessive disorder in which progressive macular degeneration can lead to blindness during the first to fourth decades. The hair may be morphologically normal or show a variety of nonspecific shaft abnormalities. The disease results from mutations in CDH3 encoding P-cadherin.56

Hypotrichosis–lymphedema–telangiectasia syndrome

Congenital hypotrichosis is a feature of this condition, accompanied later in life by lymphedema and telangiectasia. Mutations have been found in the transcription factor gene SOX18.57

Hypotrichosis associated with ectodermal dysplasias

Hypotrichosis (see also Chapter 29) is an important feature in many ectodermal dysplasias,58 but often becomes obvious only after the neonatal period. A selection of conditions in which there may be congenital or early-onset severe hypotrichosis or atrichia will be considered here.

Hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (Clouston syndrome)

Hypotrichosis of a variable and sometimes very severe degree of scalp hair, eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair is usually present at birth.59 Any hair present is fine and fragile. Later significant features are leukoplakia, nail dystrophy, and palmoplantar keratoderma. The condition is caused by mutations in GJB6, coding connexin 30.59 Rare cases of Clouston syndrome have sensorineural deafness which may represent a contiguous gene syndrome resulting from deletion of the GJB6 gene and of the connexin-26 gene (GJB2).60

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia

This condition may be inherited due to one of four defects: (1) the EDA gene, which encodes ectodysplasin-A on Xq13.1, leading to X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED); (2) the ectodysplasin receptor (EDAR) on 2q12.3, with autosomal dominant and recessive forms; (3) the EDAR death domain (EDARADD) on 1q42-q43, with autosomal dominant and recessive forms; (4) the NEMO gene on Xq28, which presents with immunodeficiency, and occasionally osteopetrosis and lymphedema.61

The majority of cases represent a mutation in the EDA gene and are characterized by marked hypotrichosis of all hair-bearing areas, often evident in the neonatal period; hair that is present is fine and fair, and often shows pili canaliculi on microscopy. Other features that may be evident in the neonatal period include impaired heat regulation, diffuse scaling of skin, hypoplastic or absent nipples, and the typical facies with a depressed nasal bridge and prominent brow.62 Rouse and colleages63 reported that scalp biopsies from patients with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (HED) demonstrate an absence of eccrine structures in the majority of cases. Their absence is diagnostic of HED, and their presence suggests that the patient does not have this disorder. As the eccrine apparatus is fully formed by the third trimester this test should be reliable in the neonate.63

Ankyloblepharon, ectodermal dysplasia and clefting syndrome, and Rapp–Hodgkin syndrome

At birth in the ankyloblepharon, ectodermal dysplasia and clefting syndrome (AEC, Hay–Wells), the scalp is usually red and scaly with extensive erosions and crusts, and there is a severe hypotrichosis (Fig. 31.14).64 Other neonatal features include a generalized erythroderma with or without erosive lesions, ankyloblepharon filiforme, lacrimal duct atresia, cleft palate and lip, and hypoplastic nails. Both Rapp–Hodgkin and AEC syndromes have mutations in 3q27 which encodes the p63 gene. As such, they are currently viewed as related disorders, with reported cases of Rapp–Hodgkin syndrome sharing all the features of AEC apart from the ankyloblepharon.58,65

Bazex–Dupré–Christol syndrome

The main features of this probably X-linked dominant condition are congenital hypotrichosis, milia with onset in the first 3 months of life, the later appearance of follicular atrophoderma as the milia are shed, and early development of basal cell carcinomas.18 Microscopic hair shaft examination may show trichorrhexis nodosa and an irregular twisting.

Congenital atrichia with nail dystrophy, abnormal facies, and retarded psychomotor development

In this condition, after the shedding in the first weeks of life of an initial sparse cover of hair, there is almost total alopecia with only tiny vellus hairs being evident; scalp biopsy demonstrates atrophy of hair follicles and rudimentary hair shafts.66 Nail dystrophy and an abnormal facies with a broad nasal bridge, hypertelorism, a broad nose, and a long philtrum are other congenital features.

Hypotrichosis associated with ichthyoses

Ichthyoses presenting as the collodion baby phenotype

In this group of conditions (see also Chapter 19), which includes autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant forms of lamellar ichthyosis, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, and lamellar ichthyosis of the newborn (self-healing collodion baby), the hair is often either absent or shed in the early weeks of life with the collodion scale (Fig. 31.15).

Congenital ichthyosis, follicular atrophoderma, hypotrichosis, and hypohidrosis

This combination of traits has been described as a new autosomal recessive genodermatosis.67 Hypotrichosis of scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes is evident in the neonatal period, and the ichthyosis and follicular atrophoderma are both also congenital. Woolly hair was an additional feature in one case.67

Keratitis, ichthyosis, and deafness (KID) syndrome

Severe hypotrichosis of scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes may be evident at birth (Fig. 31.16). Other congenital features include spiny follicular plugs, perioral furrowing, reticulate hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, widespread thickened erythematous plaques, and hearing loss. The condition is usually caused by mutations in GJB2, encoding connexin 26.48,59

Ichthyosis follicularis, congenital atrichia, and photophobia (IFAP)

From birth these individuals demonstrate keratotic follicular papules, atrichia, or severe hypotrichosis and photophobia.68 A variety of other features can be present and there are pedigrees suggesting both X-linked recessive and autosomal dominant inheritance. Happle69 suggests there may be more than one syndrome within this designation. A functional deficiency of a zinc metalloprotease causes the disease (MBTPS2).70

Hypotrichosis with hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia

Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia is a dominantly inherited disease characterized by congenital nonscarring hypotrichosis with coarse abnormal hair, gingival erythema, severe keratitis, follicular keratotic papules, and periorificial psoriasiform plaques.71 It has been suggested that this and IFAP may be the same condition, but there are sufficiently different features to make it likely they are separate entities. Searches for abnormal expression of gap junction and desmosomal proteins have so far been unrewarding.71

Hypotrichosis with premature aging syndromes

Although the onset of obvious hypotrichosis is often delayed until several years of age in these conditions, in some cases of Hutchison–Gilford progeria, Cockayne syndrome, and Rothmund–Thomson syndrome, sparse hair is evident in early infancy. A severe neonatal progeroid syndrome has been described in which severe hypotrichosis is evident at birth, along with redundant skin, absent subcutaneous fat, and prominent blood vessels.72

Hypotrichosis with immunodeficiency syndromes

In cartilage hair hypoplasia syndrome, sparsity of scalp, eyebrow, and eyelash hair is often evident in the neonatal period, together with short limbs and prenatal growth failure.73 A human homologue of the nude mouse has recently been identified with mutations in the winged helix nude gene leading to complete absence of all hair and severe immunodeficiency.49 Alopecia is also often a striking feature of a heterogeneous group of congenital immunodeficiency conditions presenting with erythroderma, failure to thrive, and diarrhea in early infancy, including Omenn syndrome and severe combined immunodeficiency-associated congenital graft-versus-host disease.74

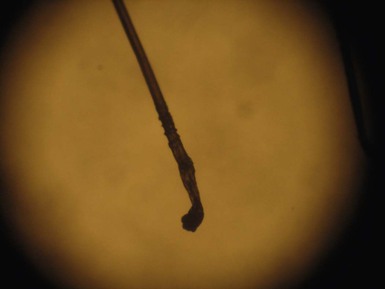

Loose anagen syndrome

Loose anagen syndrome (LAS) is a benign, self-limiting condition where anagen hairs are easily and painlessly extracted. Although this condition is not seen neonates, it may become evident in infants or toddlers because of the very sparse growth of hair with wispy ends. Because the hair pulls out easily patchy alopecia occasionally is noted (Fig. 31.17). LAS is a sporadic or autosomal dominant disorder with variable expressivity that has been linked to the genes encoding K6HF, the companion layer keratin and K6IRS, a gene specific for the internal root sheath. It can also be seen in Noonan syndrome and certain ectodermal dysplasias. A trichogram reveals a characteristic ruffling of the cuticle (Fig. 31.18![]() ) and may show misshapen anagen bulbs and long, tapered and twisted hairs. Most cases of LAS improve spontaneously with age.

) and may show misshapen anagen bulbs and long, tapered and twisted hairs. Most cases of LAS improve spontaneously with age.

Localized alopecia (Box 31.4)

Trauma

Alopecia in the neonatal period may occur in areas of scalp damaged by instrumentation, such as forceps, scalp monitors, and vacuum extractor, and also around a caput succedaneum (see Chapter 8). Prolonged pressure on the scalp by the cervical os during or before the delivery may result in a distinctive pattern of annular alopecia known as a halo scalp ring (Fig. 31.19).

Neonatal occipital alopecia

A well-defined patch of alopecia commonly develops in the occipital area in the early months of life (Fig. 31.20). This has been attributed to pressure or friction due to sleeping in a supine position and/or rubbing against the bedding surface, but is explained more fully by an understanding of the patterns of hair cycle evolution in fetal and early neonatal life.75 Although the hair roots enter catagen and then telogen in a progressive manner from frontal to parietal areas at 26–28 weeks’ gestation, the roots in the occipital area remain in anagen until around the time of birth, when they abruptly enter telogen. These hairs inevitably fall 8–12 weeks later. Thus neonatal occipital alopecia is really a form of localized telogen effluvium. Often, there are considerable numbers of hairs in the parietal area still in telogen at birth, and a more extensive postnatal alopecia can occur, leaving hair only on the vertex. In pigmented races, there is a delay in onset of these physiologic changes as most roots are still in anagen at birth, and the mean diameter of the hairs is greater than in fair-complexioned neonates. For these reasons, the hair is often prolific at a time when the fair neonates are developing significant alopecia.

Triangular alopecia

This noncicatricial circumscribed area of hypotrichosis is triangular or lance-shaped and is positioned in the frontotemporal area, with the base facing the temporal edge of the hairline but sometimes separated from it by a small fringe of normal hair (Fig. 31.21).76 It is unilateral in 80% of cases. It is a hypotrichosis rather than a true alopecia because vellus hairs are present in the affected area. Occasionally a few terminal hairs are retained. Although the condition usually occurs sporadically it may very rarely affect several members of a family, and Happle77 has suggested it may be a paradominant trait; he notes that it has occurred in association with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis, providing further evidence that it may result from loss of heterozygosity.77 Histopathologic examination of transverse sections of a biopsy specimen demonstrates that the majority of follicles are vellus; a normal number of follicles are present, but their size is abnormal for the scalp.76 The condition certainly may be congenital and may be noted in the neonatal period in infants with abundant scalp hair, in whom it is often erroneously ascribed to forceps trauma. Whether it is always congenital is disputed.76

Tinea capitis

Although rare, tinea capitis (see Chapter 14) can occur in neonates and more commonly in infants and can cause localized scaling and alopecia (Fig. 31.22![]() ). At times, it may present as a purulent scalp lesion.78 As in older children, systemic antifungals are necessary to achieve cure.

). At times, it may present as a purulent scalp lesion.78 As in older children, systemic antifungals are necessary to achieve cure.

Traction alopecia and trichotillomania

In the African-American population, hair-braiding practices, particularly ‘cornrows’, may predispose to traction alopecia in young children.79 Occasionally, trichotillomania is seen in infancy.80 Trichotillomania in early childhood is generally considered a benign habit disorder however even at a very early age, it can be an early sign of obsessive compulsive or other behavioral tendencies.

Aplasia cutis congenita

Aplasia cutis congenita (ACC) is a congenital defect of the skin characterized by localized absence of the epidermis, dermis and, at times, underlying tissue (Fig. 31.23). Most cases are sporadic and isolated, although it may be associated with teratogenic, local or systemic anomalies (see below).81

Localized alopecia associated with other nevoid conditions

Aplastic nevus (minus nevus)

This is a nevoid condition in which there is a complete absence of skin appendages in an area of otherwise normal skin.82

Nevus sebaceus

Nevus sebaceus are characteristically hairless. Occasionally the affected area is so flat and subtle that it is only recognized later, such that the initial presentation is as a patch of congenital alopecia (Fig. 31.24). Large sebaceus nevus can be associated with eye and neurological impairment in nevus sebaceus syndrome. Rarely, it can be seen in conjunction with aplasia cutis congenita and other multiple anomalies in SCALP syndrome.83

Nevus psiloliparus

The name nevus psiloliparus is derived from the Greek words psilos for hairless and liparos for fatty, describing the smooth-surfaced, soft, hairless lesion seen on the scalp. It can present in isolation (Fig. 31.25) or in encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis.84

Congenital melanocytic nevus

These lesions (see also Chapter 24) are usually associated with hypertrichosis, but large, folded lesions on the scalp causing an appearance of cutis verticis gyrata may have sparse covering hair (Fig. 31.26![]() ).

).

Cranial meningoceles, encephaloceles and heterotopic meningeal or brain tissue

These (see also Chapter 9) present characteristically as tumors or cysts that are either hairless or have sparse overlying hair. There is often a surrounding collar of long hair. Membranous aplasia cutis, which is in the same spectrum, representing a forme fruste of neural tube defect, presents as a hairless plaque, sometimes also with a collar of longer hair (see below).

Alopecia areata

This condition is uncommon in infancy, and rarely occurs at birth.85 The alopecia can be localized or generalized (Figs 31.27, 31.28![]() ). The diagnosis is made clinically, supported by a positive pull-test, exclamation point hairs, and spontaneous regrowth. The characteristic lymphocytic infiltrate around the hair bulb on cutaneous histopathology can confirm the diagnosis. Patients with an earlier age of onset tend to have a greater severity of disease, in terms of extent of alopecia and chance of regrowth,86 although early age of onset does not rule out future hair regrowth.87 Therapies for alopecia areata in this age group include topical corticosteroids, topical minoxidil, and most importantly patient and family support.85

). The diagnosis is made clinically, supported by a positive pull-test, exclamation point hairs, and spontaneous regrowth. The characteristic lymphocytic infiltrate around the hair bulb on cutaneous histopathology can confirm the diagnosis. Patients with an earlier age of onset tend to have a greater severity of disease, in terms of extent of alopecia and chance of regrowth,86 although early age of onset does not rule out future hair regrowth.87 Therapies for alopecia areata in this age group include topical corticosteroids, topical minoxidil, and most importantly patient and family support.85

Localized alopecia associated with syndromes

Hallermann–Streiff syndrome

The hair may be normal at birth, but in some cases the typical alopecia, located in the frontal and parietal areas over the cranial sutures, may be evident in early months together with atrophic facial skin and multiple craniofacial and ocular abnormalities.88

X-linked dominant conditions

Several rare syndromes caused by X-linked dominant genes that interfere with hair growth produce a mosaic pattern of alopecia in affected females as a result of functional X-chromosome mosaicism.89 The hemizygous males with these conditions rarely survive. The conditions include incontinentia pigmenti, focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome), X-linked dominant chondrodysplasia punctata, orofacial digital syndrome, and CHILD syndrome. The alopecia in these conditions has a patchy distribution, sometimes obviously linear or spiral as it follows the lines of Blaschko.89

Diffuse hypertrichosis

The term ‘hypertrichosis’ refers to increased hair, whereas hirsutism refers specifically to increased hair in hormonally responsive areas of skin (such as the axillae, pubic area, and beard area). Hirsutism in neonates and young infants is rare and is virtually always a result of congenital endocrine disorders. Hypertrichosis, on the other hand, can result from a wide variety of conditions.

Primary hypertrichosis

There is much confusion about congenital hypertrichosis occurring alone or with only occasional associations, because of the wide variety of designations given and the poor clinical descriptions in the early literature. Baumeister and colleagues,90 and more recently, Garcia-Cruz and coworkers,91 have attempted to clarify the classification, but some confusion persists. However, several apparently individual entities can be separated out (Box 31.5).

Transient diffuse hypertrichosis

Lanugo is the fine unmedullated hair that is present in the fetus. The hairs are several centimeters long and usually nonpigmented.92 Growth occurs on the entire body, including the face. This hair is normally shed at around 7–8 months’ gestation. However, in some neonates, especially if premature, diffuse lanugo hair is still present and is most marked on the shoulders, posterior trunk, cheeks and sometimes ears (Fig. 31.29). This is then shed in the early weeks of life.

Hypertrichosis lanuginosa

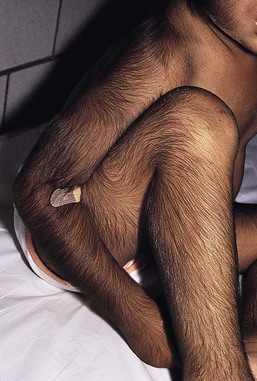

This rare condition is characterized by prolonged retention of lanugo hair. The infant is born with a coat of profuse, long, silky, fine, hair on all the usual hair-bearing areas.93 It may reach 10 cm in length and blends with the terminal hair of scalp and eyebrows (Fig. 31.30). There may be accentuation in certain areas, particularly over the spine and on the pinnae. Profuse growth in the ear canal may lead to infection and reduced hearing, and needs to be cleared. Matted hair in the diaper area is particularly troublesome, and shaving or laser hair removal in this and other areas may be indicated. A 40–80% reduction in hair has been noted in laser-treated areas using low fluences to minimize pain.94–96 At puberty, there may be no conversion to terminal hair in secondary sexual hair areas, with long, fine, lanugo hairs growing in the beard, pubic, and axillary areas. Although about one-third of cases are sporadic, autosomal dominant inheritance is well established.91,93 However, a single family with possible autosomal recessive inheritance has also been reported. Most patients are free of other abnormalities, but congenital glaucoma, skeletal,97 and dental94 abnormalities, including neonatal teeth, have been observed.

Prepubertal hypertrichosis

A series has been reported98 of otherwise healthy children, with no clinical evidence of endocrinopathy, having generalized hypertrichosis present from birth and increasing in severity in early childhood. There is terminal hair growth on the temples, spreading across the brow and merging with bushy eyebrows, and also profusely on the back and proximal limbs.98 The pattern does not resemble hirsutism and hair growth on the back is in an inverted fir tree distribution, centering on the spine. It is not clear whether this represents an abnormality or whether it is an extreme form of the normal range of hair growth, resembling as it does the patterns of hair growth seen regularly in some racial groups.98 However, a 2000 study has demonstrated that testosterone levels and the free androgen index are increased in patients compared to controls. This suggests that an endocrine imbalance may indeed be the basis for this condition.99

X-linked dominant hypertrichosis

A pedigree has been reported with probable X-linked dominant inheritance where affected members have generalized terminal hair hypertrichosis present at birth.100 The face, pubic area, back, and upper chest are most involved, but the palms, soles, and mucosae are spared. There is no gingival hyperplasia. After puberty there may be an improvement on the trunk and limbs. This condition has been mapped to a 22-cM interval between DXS425 and DXS1227 on chromosome Xq24-q27.1.101

Ambras syndrome

Baumeister and colleagues102 have delineated what they regard as a unique form of diffuse congenital hypertrichosis which has been previously reported under a variety of names, and have demonstrated a balanced structural chromosomal aberration in a patient with this condition. It has been designated ‘Ambras syndrome’ in reference to the first documented case. The hair, which may demonstrate pigmentation and medullation, is said to be vellus rather than lanugo. The hypertrichosis is most marked on the face, nose, ears, and shoulders, and the forehead, eyelids, cheeks, and preauricular regions show hair of variable lengths.91 The palms, soles, mucous membranes, dorsal terminal phalanges, labia minora, prepuce, and glans penis are always spared.91 The hypertrichosis persists throughout life. A number of dysmorphic facial features (coarse face, wide intercanthal distance, broad palpebral fissures, broad interalar distance and anteverted nares) and dental abnormalities (anodontia and delayed secondary dentition) may be present.91,103 An autosomal dominant inheritance is proposed, with the causative gene mutation found on chromosome 8q22-q24.91,103

Hypertrichosis as part of other genetically determined disorders

Many syndromes have hypertrichosis as a feature, and in some of these it is present in the neonatal period. A selection of these conditions is considered here.

Hypertrichosis with gingival fibromatosis

Hypertrichosis and gingival fibromatosis may occur as a dominantly inherited trait and is usually caused by microdeletions on chromosome 17q24.2-q24.3.92,104,105 The hypertrichosis is usually of terminal hair, but may be relatively mild. It can be present at birth or develop during early infancy, but in up to half of the reported cases the hypertrichosis begins at puberty.97 The gingival hyperplasia appears later in childhood. Other clinical features include a coarse facies with a wide, flat nose and thick lips, and large ears.91

Several patients have been reported with epilepsy and mental retardation in association with severe hypertrichosis and gingival fibromatosis.106 The gingival fibromatosis in this condition usually presents in the second decade but has been reported in infancy. The hypertrichosis is congenital, and the hair varies from fine to coarse and is pigmented. The face, arms, and lumbosacral area are most severely affected. It is possible that these conditions are within a single spectrum.

Further overlap is suggested with the Laband syndrome of gingival hyperplasia, dysplasia of the terminal phalanges, hepatosplenomegaly, and facial dysmorphism, with the recent report of marked congenital hypertrichosis as an additional feature in one patient.107

Hypertrichosis with osteochondrodysplasia

This rare syndrome (also known as Cantu syndrome) is the combination of diffuse congenital hypertrichosis, congenital macrosomia, cardiomegaly which may also be present at birth, and a variety of skeletal changes.91 The hair changes from lanugo to postnatal hair, which continues to grow in length and diameter, extending all over the body but sparing the palms, soles, and mucosae.91 It is most marked on the face, with involvement of the forehead and thick eyebrows, and there is a low posterior cervical hairline. Other features include mild mental retardation, macrocephaly, global cardiomegaly due to cardiomyopathy (sometimes complicated by pericarditis with effusion),91 and a variety of skeletal changes, including a wide posterior fossa in the skull, a verticalized base of the cranium, narrow thorax, broad ribs, bilateral coxa valga, a short distal phalanx of the thumbs and first toes, and hypertrophy of the first metatarsals.91 Most cases are autosomal dominant and are caused by heterozygous mutation in the ABCC9 gene on chromosome 12p12.108

Hypertrichosis with congenital eye disorders

Hypertrichosis, pigmentary retinopathy, and facial anomalies.

An apparently distinct form of congenital hypertrichosis has been reported in one male patient.109 At birth, long, fine, dark hair covered the shoulders, back, buttocks, and limbs; the chest and abdomen were relatively spared. A biopsy from an arm showed a smooth muscle proliferation suggestive of smooth muscle hamartoma. Associated findings were pigmentary retinopathy and dysmorphic facial features. The finding of hypopigmented and hyperpigmented streaks following Blaschko’s lines on the limbs suggested mosaicism, but this could not be confirmed on chromosomal studies of lymphocytes and skin fibroblasts.109

Hypertrichosis with cone/rod dystrophy.

In 1999, Jalili110 reported two female cousins with Leber’s amaurosis, with cone/rod dystrophy and congenital hypertrichosis.91 They had severe retinal dystrophy with visual impairment from birth and profound photophobia in the absence of night blindness. Trichomegaly, bushy eyebrows with synophrys, and excessive facial and body hair, including hypertrophied circumareolar hair on the breast, were present. An autosomal recessive inheritance pattern was proposed.110

Hypertrichosis with congenital cataracts and mental retardation.

A new autosomal recessive syndrome characterized by congenital lamellar cataracts, generalized hypertrichosis on the back, shoulders, and face, and mental retardation (CAHMR syndrome) was reported in 1992.111 Associated findings were a low hairline, high narrow palate, macrodontia, and pectus excavatum.111

Coffin–Siris syndrome

Hypertrichosis is a feature in many cases,112 particularly of the face and back; there is a low frontal hairline, bushy laterally displaced eyebrows, and long eyelashes, but often sparse scalp hair. Also evident in the neonatal period are absence or hypoplasia of the nails and distal phalanges of the fifth fingers and toes, microcephaly, facial dysmorphism, and low birthweight. Short stature is common, as is delayed bone age. Spinal anomalies are also frequently seen, including sacral dimples, spina bifida occulta, scoliosis, and kyphosis. Mental retardation becomes evident later. The region 7q32–34 is a candidate region for the gene responsible for this syndrome.113

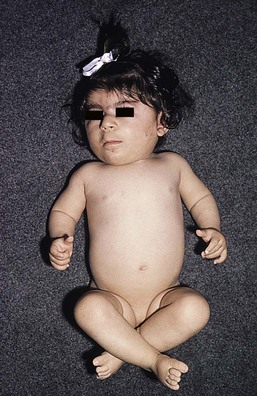

Cornelia de Lange syndrome

There is a mild generalized hypertrichosis with low frontal and occipital hairlines, thick eyebrows, synophrys, and long, upturned lashes (Fig. 31.31). The hair on the lateral elbows and sacral area may be very long and fine. Other features notable in the neonatal period include congenital livedo, low birthweight, feeding difficulties, increased susceptibility to infection, and an unusual low-pitched growling cry. There is a distinctive facies with hypertelorism, an antimongoloid slant of the palpebral fissures, long philtrum, and thin lips. Other features in occasional cases include micromelia and phocomelia, cryptorchidism, and hypospadias.

Leprechaunism (Donohue syndrome)

These infants have coarse, curly scalp hair, and 75% of cases have extensive body and facial hypertrichosis.114 There is low birthweight, wrinkled loose skin with reduced or absent subcutaneous fat, acanthosis nigricans, periorificial rugosity of skin, thick lips, gingival hypertrophy, large low-set ears, and hypertrophic external genitalia.

Seip–Berardinelli syndrome (congenital generalized lipodystrophy)

Hypertrichosis of the face, neck, and limbs may be present at birth. There is thick, curly scalp hair with a low frontal hairline. Other features that may be evident in the neonatal period include deficiency of subcutaneous fat, acanthosis nigricans, organomegaly, and hypertrophy of genitalia.

Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome

In Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome, hypertrichosis of the trunk, limbs, and face occurs in two-thirds of cases.115 The eyebrows are highly arched and the eyelashes unusually long. There are downward-sloping palpebral fissures and mental retardation. Other features evident in the neonatal period include capillary vascular malformations, pilomatricomas, keloid formation, beaked nose, hypertelorism, cryptorchidism, broad thumbs and great toes, and sometimes broad terminal phalanges of the other digits. This syndrome is sporadic in nature and has been linked to a deletion in the CREBBP and EP300 genes.116

Barber–Say syndrome

In this rare syndrome, extensive generalized hypertrichosis, most marked over the forehead and back, is associated with redundant atrophic skin showing changes of premature aging, coarse face with bilateral ectropion, hypertelorism, absent eyebrows and lashes, bulbous nose with anteverted nares, macrostomia, abnormal ears, ectropion, hypoplastic nipples, and failure to thrive.91,117 Other features, less frequently reported, include strabismus, nystagmus, mental retardation, small teeth, and high arched palate.91

Drug-induced neonatal hypertrichosis

Fetal alcohol syndrome

Neonatal hypertrichosis is an occasional feature of this condition.118 The infant is small and microcephalic with dysmorphic facial features, including short palpebral fissures, microphthalmia, midfacial hypoplasia, and a long philtrum.

Maternal minoxidil

Maternal use of minoxidil during pregnancy has been associated with a striking hypertrichosis of the back and extremities in the neonate, accompanied by multiple dysmorphic facial features, uneven fat distribution, omphalocele, and cardiac anomalies.119

Diazoxide

Diazoxide is commenced in babies with hyperinsulinemia as soon as the diagnosis is established, usually in the first week of life; hypertrichosis of brow, limbs, and back becomes obvious in the first 4 weeks of treatment and is dose dependent.

Localized congenital hypertrichosis

Localized hypertrichosis may occur in association with certain nevi or developmental abnormalities (Box 31.6).

Congenital melanocytic nevus

Congenital melanocytic nevi may be covered with dense, dark terminal hair at birth over part or all of their surface (Fig. 31.32). In areas other than the scalp, the degree of hairiness is usually proportional to the degree of elevation of the lesion. On the scalp, however, even very flat lesions often have a dense covering of hair that is longer, darker, and coarser than the surrounding scalp hair.

Congenital smooth muscle hamartoma

These nevi present most commonly as congenital, slightly elevated, pebbly, firm skin-colored or slightly pigmented plaques, with local hypertrichosis (Fig. 31.33).120 Most occur on the trunk or the proximal extremities, but other areas, including the scalp,121 may be affected. A pseudo-Darier sign of transient piloerection or elevation of the lesion after it is rubbed is a characteristic feature. Extensive hypertrichosis overlying diffuse, widespread, smooth muscle hamartomas has also been reported.122 Histopathologic examination demonstrates a proliferation of variably oriented smooth muscle bundles, often associated with hair follicles. There may also be epidermal changes of acanthosis and papillomatosis, as seen in Becker nevus.

Becker nevus usually presents in late childhood or adolescence as a patch of thickened, pigmented, hypertrichotic skin. Congenital cases have been reported, although usually lacking hypertrichosis in the neonatal period.123 These nevi are uncommon in females.120 An unusual presentation with congenital bilaterally symmetric lesions, hypertrichotic at birth, has been reported.124 Some believe that congenital smooth muscle hamartoma and Becker nevus are in a spectrum,125 but others feel they are distinct entities.126

Plexiform neurofibroma

The skin over these lesions is often notable for a patch of hyperpigmentation with an irregular border and hypertrichosis of varying degree.127 A prominent paraspinal hair whorl may also occur at the site of a deep mediastinal plexiform neurofibroma.128 A similar paraspinal whorl has been described in a patient with a posterior mediastinal ganglioneuroma.129 Erythema may also be a feature, leading to confusion with vascular tumors such as tufted angiomas and kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas, that may themselves have associated focal hypertrichosis.

Tufted angioma

This is a rare benign vascular tumor found particularly on the neck and upper trunk regions, as well as the abdomen, groin, and lower limbs. Most commonly they present as dusky red to violaceous, indurated, subcutaneous plaques or nodules; 30% of lesions are tender.130 Some have been associated with focal hyperhidrosis and/or hypertrichosis.131

Hypertrichosis with spinal dysraphism

Isolated hypertrichosis in the lumbosacral region may be a normal variant and is usually genetically or racially determined. It should be distinguished from hypertrichosis associated with an underlying spinal abnormality. This latter presents at birth as a tuft of long, silky hair (faun tail) with or without the presence of other cutaneous markers, such as a dimple, sinus tract, aplasia cutis, lipoma with deviation of the gluteal fold, capillary malformation, hemangioma, or a pigmented nevus.132–134 These cutaneous lesions may be found in the presence of clinical spina bifida with myelomeningocele (Fig. 31.34![]() ), but are particularly helpful as markers for occult spinal dysraphism. Two or more congenital midline skin lesions constitute a particularly strong marker for spinal dysraphism.134 Hypertrichosis associated with spinal fusion abnormalities may also occur less commonly over other areas of the spine.

), but are particularly helpful as markers for occult spinal dysraphism. Two or more congenital midline skin lesions constitute a particularly strong marker for spinal dysraphism.134 Hypertrichosis associated with spinal fusion abnormalities may also occur less commonly over other areas of the spine.

Familial cervical hypertrichosis dysraphism

A family has been reported with congenital localized hypertrichosis of the cervical area overlying a kyphoscoliosis without other spinal or cutaneous abnormalities.135 The inheritance pattern was autosomal dominant.

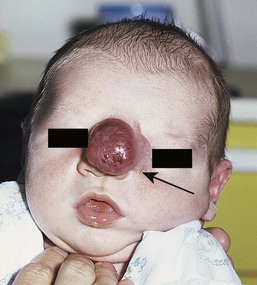

Hypertrichosis with cranial meningoceles, encephaloceles, and heterotopic meningeal or brain tissue

These conditions are described in detail in Chapter 9. They are often marked by a peripheral collar of hair (Fig. 31.35), a tuft of hair nearby, or overlying hair.133 In scalp lesions the hair is longer, thicker, and often darker than the surrounding normal hair. An associated vascular stain may also be present.136 With lesions outwith the scalp, the presence of hair may indicate a neural lesion (Figs 31.36![]() , 31.37). Prominent hair follicle orifices may also be a feature. It is now clear that the membranous form of aplasia cutis, which may also demonstrate a hair collar and which can occur on the face133,137,138 as well as the scalp, is a form fruste of a neural tube closure defect and in the same spectrum as cranial meningoceles, encephaloceles, and heterotopic brain tissue.133 A patient has been reported with a congenital patch of hypertrichosis over the lumbar area, well away from the spine, overlying what was demonstrated histologically to be meningeal tissue; in this case, displacement of meningeal cells along nerves during embryogenesis is postulated as the mechanism, rather than entrapment of meningeal membranes at the time of closure of the neural tube.139

, 31.37). Prominent hair follicle orifices may also be a feature. It is now clear that the membranous form of aplasia cutis, which may also demonstrate a hair collar and which can occur on the face133,137,138 as well as the scalp, is a form fruste of a neural tube closure defect and in the same spectrum as cranial meningoceles, encephaloceles, and heterotopic brain tissue.133 A patient has been reported with a congenital patch of hypertrichosis over the lumbar area, well away from the spine, overlying what was demonstrated histologically to be meningeal tissue; in this case, displacement of meningeal cells along nerves during embryogenesis is postulated as the mechanism, rather than entrapment of meningeal membranes at the time of closure of the neural tube.139

Nevoid hypertrichosis

Several patients have been reported with single or multiple localized patches of terminal hair arising in skin which is otherwise normal in color and texture (Fig. 31.38).120,140,141 Presentation is usually at or soon after birth, although the development of additional patches after puberty has been described. The color of the hair is typically the same as that of the scalp, but rarely the hair may be paler or there may be premature graying. In one case, underlying lipoatrophy was found in some patches.140 Additional abnormalities seen in another patient included areas of lipoatrophy and streaky depigmentation away from the areas of hypertrichosis, developmental delay and seizures, congenital lung cysts, congenital malrotation of the gut, and multiple skeletal, dental, and ocular abnormalities.141 This constellation of findings did not fit into any recognized syndrome. The excess hair can be treated with laser.142

There have also been a few cases of hypertrichosis overlying lesions of nevus spilus.142

Hemihypertrophy with hypertrichosis

Hemihypertrophy is a rare congenital disorder in which the whole of one side of the body or, less commonly, part of one side of the body is enlarged. Serious associated malformations include Wilms tumor and tumors of the brain and adrenals. The skin is often normal, but cutaneous abnormalities reported include pigmentation, telangiectasia, abnormal nail growth, and hypertrichosis, which can be very striking.143

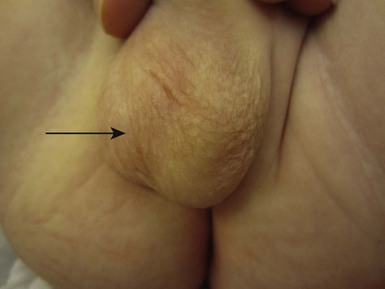

Scrotal hair

Several infant boys have been reported who developed scrotal hair within the first 3 months of life in the absence of clinical or biochemical evidence of excess androgen production (Fig. 31.39![]() ).144 The condition is not progressive and most cases are sporadic. It is most likely caused by an increased hypersensitivity of scrotal hair follicles in affected infants to the normal ‘physiological’ high concentrations of testosterone seen in early infancy.144 As concentrations decrease later in infancy, the scrotal hair disappears or diminishes. Although this is a benign condition, it should be regarded only as a diagnosis of exclusion and all infants with signs suggestive of androgenization should be fully investigated.

).144 The condition is not progressive and most cases are sporadic. It is most likely caused by an increased hypersensitivity of scrotal hair follicles in affected infants to the normal ‘physiological’ high concentrations of testosterone seen in early infancy.144 As concentrations decrease later in infancy, the scrotal hair disappears or diminishes. Although this is a benign condition, it should be regarded only as a diagnosis of exclusion and all infants with signs suggestive of androgenization should be fully investigated.

Anterior cervical hypertrichosis

A congenital patch of hypertrichosis localized to the front of the neck at the sternal notch has been described and the inheritance pattern is most likely autosomal recessive.91,145 Although usually an isolated finding, it may be associated with peripheral sensory and motor neuropathy,146 retinal abnormalities, developmental delay and learning difficulities.147

Hairy cutaneous malformations of palms and soles

There have been reports of the familial occurrence of hair growth on circumscribed areas of the palms and soles.148 In one family, the skin in the area showed exaggerated markings in a geometric pattern. The condition was present at birth and persisted throughout life. Histopathology demonstrated the presence of ectopic hair follicles and some increase in the amount of elastic fibers in the dermis.

Hypertrichosis cubiti

In ‘hairy elbows syndrome’ lanugo hairs are present symmetrically at birth or develop during infancy on the extensor surfaces of the elbows, extending from midhumerus to midforearm.97,149 This syndrome is not usually associated with other anomalies and most frequently only represents a cosmetic problem. There have, however, been isolated case reports of hypertrichosis cubiti associated with short stature.149

Ectopic cilia

The eyelashes or cilia are modified hairs originating from follicles on the margins of the eyelids. The rarest of all cilial anomalies is ectopic placement. The locations of the ectopic cilia fall into two distinct groups: those originating anterior to the tarsal plate and those arising from the posterior surface of the tarsus. Ectopic cilia arising anterior to the tarsal plate are all seen within the lateral quarter of the lid, with multiple hairs (15–20) surrounding a pit, and the bulbs of the follicles being tightly adherent to the underlying tarsus (Fig. 31.40![]() ). Ectopic cilia originating from the posterior surface of the tarsal plate presents with a single lash seen beneath the conjunctiva; the position on the lid varies. The two forms of lesion have different etiologic origins.150

). Ectopic cilia originating from the posterior surface of the tarsal plate presents with a single lash seen beneath the conjunctiva; the position on the lid varies. The two forms of lesion have different etiologic origins.150

Distichiasis

This term refers to lashes arising from the Meibomian gland orifices. This can occur as a result of eyelid inflammation, but there is an inherited congenital form in which there is a double row of lashes, the normal row and a row arising from meibomian gland orifices. This condition can be inherited alone or more commonly as part of lymphedema–distichiasis syndrome. Mutations in the FOXC2 gene have been identified in both groups, suggesting they are phenotypic varieties of the same disorder.151

Hypertrichosis pinnae auris

Hypertrichosis pinnae auris, also known as ‘hairy ears’ describes the development of hairs on the outside of the pinna of the ear (Fig. 31.41). It is a benign finding seen in many ethnic groups and usually resolves with time. It may be caused by sex-limited expression of an autosomal dominant gene.152

Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com ![]()

Figures 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 18, 22, 26, 28, 34, 36, 39 and 40 are available online at ExpertConsult.com ![]()