Chapter 186 Haemophilus influenzae

Pathogenesis

Immunity

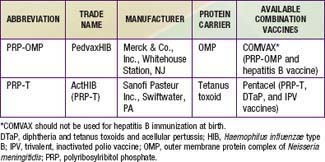

The conjugate vaccines (Table 186-1) act as thymus-dependent antigens and elicit serum antibody responses in infants and young children. These vaccines are believed to prime memory antibody responses on subsequent encounters with PRP. The concentration of circulating anti-PRP antibody in a child primed by a conjugate vaccine may not correlate precisely with protection, presumably because a memory response may occur rapidly on exposure to PRP and provide protection.

Clinical Manifestations and Treatment

Meningitis

In the pre-vaccine era, meningitis accounted for more than half of invasive H. influenzae disease. Clinically, meningitis caused by H. influenzae type b cannot be differentiated from meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis or Streptococcus pneumoniae (Chapter 595.1). It may be complicated by other foci of infection such as the lungs, joints, bones, and pericardium.

Supraglottitis or Acute Epiglottitis

Supraglottitis is a cellulitis of the tissues comprising the laryngeal inlet (Chapter 377). It has become exceedingly rare since the introduction of conjugate type b vaccines. Direct bacterial invasion of the involved tissues is probably the initiating pathophysiologic event. This dramatic, potentially lethal condition can occur at any age. Because of the risk of sudden, unpredictable airway obstruction, supraglottitis is a medical emergency. Other foci of infection, such as meningitis, are rare. Antimicrobial therapy directed against H. influenzae and other etiologic agents should be administered parenterally but only after the airway is secured, and therapy should be continued until patients are able to take fluids by mouth. The duration of antimicrobial therapy is typically 7 days.

Pneumonia

The true incidence of H. influenzae pneumonia in children is unknown because invasive procedures required to obtain culture specimens are seldom performed (Chapter 392). In the pre-vaccine era, type b bacteria were believed to be the usual cause. The signs and symptoms of pneumonia due to H. influenzae cannot be differentiated from those of pneumonia due to many other microorganisms. Other foci of infection may be present concomitantly.

Suppurative Arthritis

Large joints, such as the knee, hip, ankle, and elbow, are affected most commonly (Chapter 677). Other foci of infection may be present concomitantly. Although single joint involvement is the rule, multiple joint involvement occurs in about 6% of cases. The signs and symptoms of septic arthritis caused by H. influenzae are indistinguishable from those of arthritis caused by other bacteria.

Pericarditis

H. influenzae is a rare cause of pericarditis (Chapter 434). Affected children often have had an antecedent upper respiratory tract infection. Fever, respiratory distress, and tachycardia are consistent findings. Other foci of infection may be present concomitantly.

The diagnosis may be established by recovery of the organism from blood or pericardial fluid. Gram stain or detection of PRP in pericardial fluid, blood, or urine (when type b organisms are the cause) may aid the diagnosis. Antimicrobials should be provided parenterally in a regimen similar to that used for meningitis (Chapter 595.1). Pericardiectomy is useful for draining the purulent material effectively and preventing tamponade and constrictive pericarditis.

Bacteremia without an Associated Focus

Bacteremia due to H. influenzae may be associated with fever without any apparent focus of infection (Chapter 170). In this situation, risk factors for “occult” bacteremia include the magnitude of fever (≥39°C) and the presence of leukocytosis (≥15,000 cells/µL). In the pre-vaccine era, meningitis developed in about 25% of children with occult H. influenzae type b bacteremia if left untreated. In the vaccine era, this H. influenzae infection has become exceedingly rare. When it does occur, the child should be re-evaluated for a focus of infection and a second blood culture performed. In general, the child should be hospitalized and given parenteral antimicrobial therapy after a diagnostic lumbar puncture and chest radiograph are obtained.

Otitis Media

Acute otitis media is one of the most common infectious diseases of childhood (Chapter 632). It results from the spread of bacteria from the nasopharynx through the eustachian tube into the middle ear cavity. Usually because of a preceding viral upper respiratory tract infection, the mucosa in the area becomes hyperemic and swollen, resulting in obstruction and an opportunity for bacterial multiplication in the middle ear.

Conjunctivitis

Acute infection of the conjunctivae is common in childhood (Chapter 618). In neonates, H. influenzae is an infrequent cause. However, it is an important pathogen in older children, as are S. pneumoniae and S. aureus. Most H. influenzae isolates associated with conjunctivitis are nontypable, although type b isolates and other serotypes are occasionally found. Empirical treatment of conjunctivitis beyond the neonatal period usually consists of topical antimicrobial therapy with sulfacetamide. Topical fluoroquinolone therapy is to be avoided because of its broad spectrum, high cost, and high rate of emerging resistance among many bacterial species. Ipsilateral otitis media caused by the same organism may be present and requires oral antibiotic therapy.

Sinusitis

H. influenzae is an important cause of acute sinusitis in children, second in frequency only to S. pneumoniae (Chapter 372). Chronic sinusitis lasting >1 yr or severe sinusitis requiring hospitalization is often caused by S. aureus or anaerobes such as Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, and Bacteroides. Nontypable H. influenzae and viridans group streptococci are also frequently recovered.

Prevention

Vaccine

Two H. influenzae type b conjugate vaccines are currently marketed in the USA, PRP–outer membrane protein (PRP-OMP) and PRP–tetanus toxoid (PRP-T), which differ in the carrier protein used and the method of conjugating the polysaccharide to the protein (see Table 186-1 and Chapter 165). They are often sold in combination with other vaccines. One combination vaccine, which consists of PRP-OMP combined with hepatitis B vaccine (COMVAX, Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ), can be used for doses recommended at 2, 4, and 12-15 mo of age. Another consists of DTaP vaccine (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis), IPV vaccine (trivalent, inactivated polio vaccine) and PRP-T, (Pentacel, Sanofi Pasteur Inc., Swiftwater, PA) that can be used for doses recommended at 2, 4, 6, and 12-15 mo of age.

Adderson EE, Byington CL, Spencer L, et al. Invasive serotype a Haemophilus influenzae infections with a virulence genotype resembling Haemophilus influenzae type b: emerging pathogen in the vaccine era? Pediatrics. 2001;108:18-24.

Adegbola RA, Secka O, Lahai G, et al. Elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b (BHb) disease from the Gambia after the introduction of routine immunization with a Hib conjugate vaccine: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;366:144-150.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in five young children—Minnesota, 2008. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:58-60.

Gessner BD, Sutanto A, Linehan M, et al. Incidences of vaccine-preventable Haemophilus influenzae type b pneumonia and meningitis in Indonesian children: hamlet-randomised vaccine-probe trial. Lancet. 2005;365:43-52.

McIntyre PB, Berkey CS, King SM, et al. Dexamethasone as adjunctive therapy in bacterial meningitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials since 1988. JAMA. 1997;278:925-931.

Prymula P, Peeters P, Chrobok V, et al. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides conjugated to protein D for prevention of acute otitis media caused by both Streptococcus pneumoniae and non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae: a randomized double-blind efficacy study. Lancet. 2006;367:740-748.

Saha SK, Baqui AH, Darmstadt GL, et al. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b diseases in Bangladesh, with increased resistance to antibiotics. J Pediatr. 2005;146:227-233.

Triden L, Glennen A, Juni B, et al. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease and antibiotic susceptibility of invasive isolates in Minnesota, 2002–2005. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2007;15:373-376.

Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O’Brien KL, et al. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:903-910.

Yaro S, Lourd M, Naccro B, et al. The epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae type b meningitis in Burkina Faso. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:415-419.