Haemophilus

1. List the general characteristics within the genus Haemophilus, including general habitat, atmosphere, and temperature requirements.

2. Describe the infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae and Haemophilus ducreyi.

3. Describe the difference in the typeable and nontypeable categories of Haemophilus, their virulence factors, and the disease they cause.

4. Describe the Gram stain and colonial morphology of the various Haemophilus species.

5. Describe the isolation requirements necessary for optimal recovery of Haemophilus, including any special specimen processing or transport requirements.

6. Explain the satellite phenomenon and the chemical basis for the phenomenon.

7. List the X and V factor requirements for H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, and H. ducreyi.

8. Explain the principle of the porphyrin test.

9. Explain why routine susceptibility testing of clinical isolates for H. influenzae is only necessary on strains of clinical significance (i.e., sterile sites).

10. Correlate patient signs, symptoms, and laboratory data to identify the most probable etiologic agent associated with an infection.

Epidemiology

As presented in Table 32-1, except for Haemophilus ducreyi, Haemophilus spp. normally inhabit the upper respiratory tract of humans. Asymptomatic colonization with H. influenzae type b is rare. Although H. ducreyi is only found in humans, the organism is not part of our normal flora, and its presence in clinical specimens indicates infection.

TABLE 32-1

| Organism | Habitat (Reservoir) | Mode of Transmission |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Normal flora: upper respiratory tract | Person-to-person: respiratory droplets Endogenous strains |

| Haemophilus ducreyi | Not part of normal human flora; only found in humans during infection | Person-to-person: sexual contact |

| Other Haemophilus spp. H. parainfluenzae H. parahaemolyticus |

Normal flora: upper respiratory tract | Endogenous strains |

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

Production of a capsule and factors that mediate bacterial attachment to human epithelial cells are the primary virulence factors associated with Haemophilus spp. In general, infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae are often systemic and life threatening, whereas infections caused by nontypeable (do not have a capsule) strains are usually localized (Table 32-2). The majority of serious infections caused by H. influenzae type b are typically biotypes I and II. The development and use of the conjugate vaccine in children since 1993 has reduced the infection rate by 95% in children younger than 5 years old in the United States.

TABLE 32-2

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Diseases

| Organism | Virulence Factors | Spectrum of Disease and Infections |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Capsule: Antiphagocytic, type b most common Additional cell envelope factors Mediate attachment to host cells Unencapsulated strains: pili and other cell surface factors mediate attachment |

Encapsulated strains: Meningitis Epiglottitis Cellulitis with bacteremia Septic arthritis Pneumonia Nonencapsulated strains Localized infections Otitis media Sinusitis Conjunctivitis Immunocompromised patients: Chronic bronchitis Pneumonia Bacteremia |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Uncertain; probably similar to those of other H. influenzae | Purulent conjunctivitis single strain identified as the Brazilian purpuric fever, high mortality in children between ages 1 and 4; infection includes purulent meningitis, bacteremia, high fever, vomiting, purpura (i.e., rash), and vascular collapse |

| Haemophilus ducreyi | Uncertain, but capsular factors, pili, and certain toxins are probably involved in attachment and penetration of host epithelial cells | Chancroid; genital lesions progress from tender papules (i.e., small bumps) to painful ulcers with several satellite lesions; regional lymphadenitis is common |

| Other Haemophilus spp. and Aggregatibacter spp. | Uncertain; probably of low virulence. Opportunistic pathogens |

Associated with wide variety of infections similar to H. influenzae; A. aphrophilus is an uncommon cause of endocarditis and is the H member of the HACEK group of bacteria associated with slowly progressive (subacute) bacterial endocarditis |

Chancroid is the sexually transmitted disease caused by H. ducreyi (see Table 32-2). The initial symptom is the development of a painful genital ulcer and inguinal lymphadenopathy. Although small outbreaks of this disease have occurred in the United States, this disease is more common among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations inhabiting tropical environments. Epidemics of disease are associated with poor hygiene, prostitution, drug abuse, and poor socioeconomic conditions.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimen Collection and Transport

Haemophilus spp. can be isolated from most clinical specimens. The collection and transport of these specimens are outlined in Table 5-1, with emphasis on the following points. First, Haemophilus spp. are susceptible to drying and temperature extremes. Therefore, specimens suspected of containing these organisms should be inoculated to the appropriate media immediately. Specimens susceptible to contamination with normal flora such as a lower respiratory specimen should be collected by bronchioalveolar lavage. In cases of pneumonia or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) infection or suspected infection of any other normally sterile body fluid, blood cultures should also be collected.

Direct Detection Methods

Direct Observation

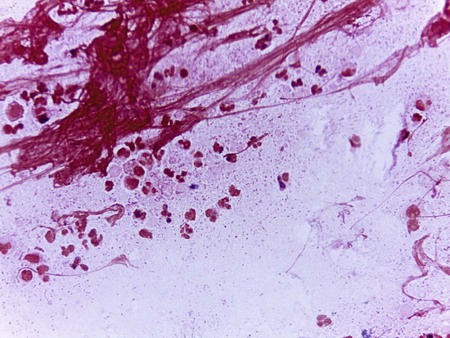

Gram stain is generally used for the direct detection of Haemophilus in clinical material (Figure 32-1). However, in some instances the acridine orange stain (AO; see Chapter 6 for more information on this technique) is used to detect smaller numbers of organisms that may be undetectable by gram staining.

To increase the sensitivity of direct Gram stain examination of body fluid specimens, especially CSF, specimens may be centrifuged (2000 rpm for 10 minutes) and the smear is prepared from the pellet deposited in the bottom of the tube. Most laboratories are now equipped with a cytocentrifuge (10,000 × g for 10 minutes) used for concentration of specimens. This is highly recommended over traditional centrifugation for non-turbid specimens. This concentration step can increase the sensitivity of direct microscopic examination from five to tenfold. Moreover, cytocentrifugation of the specimen, in which clinical material is concentrated by centrifugation directly onto microscope slides, reportedly increases sensitivity of the Gram stain by as much as 100-fold (see Chapter 71 for information on infections of the central nervous system).

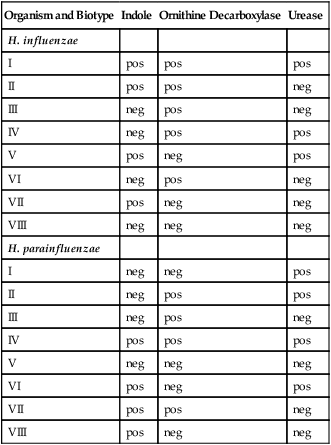

Table 32-3 presents Haemophilus influenzae and H. parainfluenzae biotypes.

TABLE 32-3

Differentiation of Haemophilus influenzae and H. parainfluenzae Biotypes

| Organism and Biotype | Indole | Ornithine Decarboxylase | Urease |

| H. influenzae | |||

| I | pos | pos | pos |

| II | pos | pos | neg |

| III | neg | pos | neg |

| IV | neg | pos | pos |

| V | pos | neg | pos |

| VI | neg | pos | neg |

| VII | pos | neg | neg |

| VIII | neg | neg | neg |

| H. parainfluenzae | |||

| I | neg | neg | pos |

| II | neg | pos | pos |

| III | neg | pos | neg |

| IV | pos | pos | pos |

| V | neg | neg | neg |

| VI | pos | neg | pos |

| VII | pos | pos | neg |

| VIII | pos | neg | neg |

Modified from Versalovic J: Manual of clinical microbiology, ed 10, Washington, DC, 2011, ASM Press.

Antigen Detection

Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide in clinical specimens, such as CSF and urine, can be detected directly using commercially available particle agglutination assays (see Chapter 9). Organisms in clinical infections are usually present at a sufficiently high concentration to be visualized by Gram stain. Therefore, most clinical laboratories no longer perform the latex test for the identification of Haemophilus spp. Latex tests are sensitive and specific for detection of H. influenzae type b, especially in patients treated with antimicrobial therapy prior to specimen collection. However, false positives have been reported in CSF and urine of patients who have recently immunized with the Hib vaccine.

Cultivation

Media of Choice

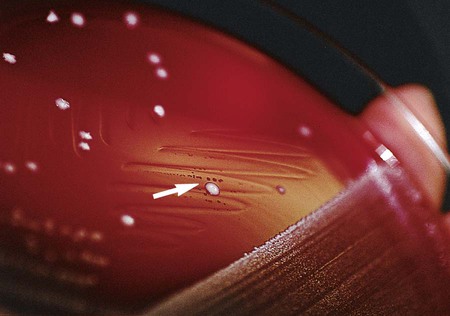

Haemophilus spp. typically grows on chocolate agar as smooth, flat or convex buff, or slightly yellow colonies. Chocolate agar provides hemin (X factor) and NAD (V factor), necessary for the growth of Haemophilus spp. Most strains will not grow on 5% sheep blood agar, which contains protoporphyrin IX but not NAD. Several bacterial species, including Staphylococcus aureus, produce NAD as a metabolic byproduct. Therefore, tiny colonies of Haemophilus spp. may be seen growing on sheep blood agar very close to colonies of bacteria capable of producing V factor; this is known as the satellite phenomenon (Figure 32-2). The satellite phenomenon has become important in this era of needing to rapidly identify potential agents of a bioterrorist attack. To examine an isolate for the satellite phenomenon, place a single streak of a hemolysin-producing strain of Staphylococcus spp. on a sheep blood agar plate that has been inoculated with a suspected Haemophilus spp. The Staphylococcus lyses the red blood cells adjacent to the streak line, releasing hemin (x factor) and NAD (v factor), providing the necessary components for growth of Haemophilus spp. Haemophilus spp. will grow adjacent to the streak line where the nutrients are available.

Colonial Appearance

Table 32-4 describes the colonial appearance and other distinguishing characteristics (e.g., odor and hemolysis) of each species.

TABLE 32-4

Colonial Appearance and Characteristics

| Organism | Medium | Appearance |

| Aggregatibacter aphrophilus | CHOC | Round; convex with opaque zone near center |

| H. ducreyi | Selective medium | Small, flat, smooth, and translucent to opaque at 48-72 hours; colonies can be pushed intact across agar surface |

| H. haemolyticus | CHOC | Resembles H. influenzae except beta-hemolytic on rabbit or horse blood agar |

| H. influenzae | CHOC | Unencapsulated strains are small, smooth, and translucent at 24 hours; encapsulated strains form larger, more mucoid colonies; mouse nest odor; nonhemolytic on rabbit or horse blood agar |

| H. influenzae biotype aegyptius | CHOC | Resembles H. influenzae except colonies are smaller at 48 hours |

| H. parahaemolyticus | CHOC | Resembles H. parainfluenzae beta-hemolytic on rabbit or horse blood agar |

| H. parainfluenzae | CHOC | Medium to large, smooth, and translucent; nonhemolytic on rabbit or horse blood agar |

| Aggregatibacter segnis | CHOC | Convex, grayish white, smooth or granular at 48 hours |

CHOC, Chocolate agar.

Approach to Identification

Traditional identification criteria include hemolysis on horse or rabbit blood and the requirement for X and V factors for growth. To establish X and V factor requirements, disks impregnated with each factor are placed on unsupplemented media, usually Mueller-Hinton agar or trypticase soy agar, inoculated with a light suspension of the organism (see Figure 13-42). After overnight incubation at 35° C in ambient air, the plate is examined for growth around each disk. Many X factor–requiring organisms are able to carry over enough factor from the primary medium to give false-negative results (i.e., growth occurs at such a distance from the X disk as to falsely indicate that the organism does not require the X factor).

Isolates from CSF or respiratory tract specimens that (1) are gram-negative rods or gram-negative coccobacilli, (2) grow on chocolate agar in CO2 but not blood agar or satellite around other colonies on blood agar, and (3) are porphyrin negative and nonhemolytic on rabbit or horse blood may be identified as H. influenzae. Haemophilus isolates may also be identified to species using rapid sugar fermentation tests; an abbreviated identification scheme for the X- and V-requiring organisms is shown in Table 32-5.

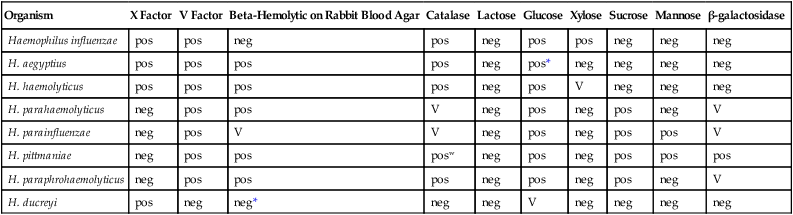

TABLE 32-5

Key Biochemical and Physiologic Characteristics of Haemophilus spp.

| Organism | X Factor | V Factor | Beta-Hemolytic on Rabbit Blood Agar | Catalase | Lactose | Glucose | Xylose | Sucrose | Mannose | β-galactosidase |

| Haemophilus influenzae | pos | pos | neg | pos | neg | pos | pos | neg | neg | neg |

| H. aegyptius | pos | pos | pos | pos | neg | pos* | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| H. haemolyticus | pos | pos | pos | pos | neg | pos | V | neg | neg | neg |

| H. parahaemolyticus | neg | pos | pos | V | neg | pos | neg | pos | neg | V |

| H. parainfluenzae | neg | pos | V | V | neg | pos | neg | pos | pos | V |

| H. pittmaniae | neg | pos | pos | posw | neg | pos | neg | pos | pos | pos |

| H. paraphrohaemolyticus | neg | pos | pos | pos | neg | pos | neg | pos | neg | V |

| H. ducreyi | pos | neg | neg* | neg | neg | V | neg | neg | neg | neg |

+, >90% of strains positive; −, >90% of strains negative; w, indicates a weak reaction; v, indicates a variable reaction.

*Delayed reactions in some strains.

Data compiled from Versalovic J: Manual of clinical microbiology, ed 10, Washington, DC, 2011, ASM Press; and Weyant RS, Moss CW, Weaver RE, et al, editors: Identification of unusual pathogenic gram-negative aerobic and facultatively anaerobic bacteria, ed 2, Baltimore, 1996, Williams & Wilkins.

Serotyping

Although serologic typing of H. influenzae may be used to establish an isolate as being any one of the six serotypes (i.e., a, b, c, d, e, and f), it is used primarily to identify type b strains. All H. influenzae from cases of invasive infections should be serotyped to determine whether or not H. influenzae type b is the cause of the infection. Testing can be performed using a slide agglutination test (see Chapter 9); a saline control without the reagent antibodies should always be tested simultaneously alongside the patient’s specimen in order to detect auto agglutination (i.e., the nonspecific agglutination of the test organism without homologous antiserum).

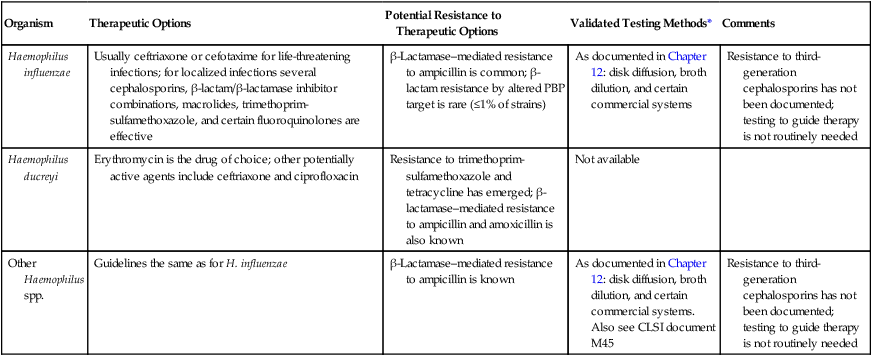

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Therapy

Standard methods have been established for performing in vitro susceptibility testing with clinically relevant isolates of Haemophilus spp. (see Chapter 12 for details on these methods). In addition, various agents may be considered for testing and therapeutic use (Table 32-6). Although widespread H. influenzae is capable of producing beta-lactamase (penicillin resistance), third-generation cephalosporins are not notably affected by the enzyme (i.e., ceftriaxone and cefotaxime) and may be effective therapeutic agents. Therefore, routine susceptibility testing of clinical isolates as a guide to therapy may not be necessary. Care should be taken when preparing inoculum concentrations (0.5 McFarland) for Haemophilus spp.; in particular, beta-lactamase-producing strains of H. influenzae, as higher suspensions may lead to false-resistant results.

TABLE 32-6

Antimicrobial Therapy and Susceptibility Testing

| Organism | Therapeutic Options | Potential Resistance to Therapeutic Options | Validated Testing Methods* | Comments |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Usually ceftriaxone or cefotaxime for life-threatening infections; for localized infections several cephalosporins, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, macrolides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and certain fluoroquinolones are effective | β-Lactamase–mediated resistance to ampicillin is common; β-lactam resistance by altered PBP target is rare (≤1% of strains) | As documented in Chapter 12: disk diffusion, broth dilution, and certain commercial systems | Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins has not been documented; testing to guide therapy is not routinely needed |

| Haemophilus ducreyi | Erythromycin is the drug of choice; other potentially active agents include ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin | Resistance to trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole and tetracycline has emerged; β-lactamase–mediated resistance to ampicillin and amoxicillin is also known | Not available | |

| Other Haemophilus spp. | Guidelines the same as for H. influenzae | β-Lactamase–mediated resistance to ampicillin is known | As documented in Chapter 12: disk diffusion, broth dilution, and certain commercial systems. Also see CLSI document M45 | Resistance to third- generation cephalosporins has not been documented; testing to guide therapy is not routinely needed |

*Validated testing methods include standard methods recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and commercial methods approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).